To the world Elliot Volkin was a distinguished scientist at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. To Karen Brunner he was simply "dad."

“That was his job. And I think growing up in Oak Ridge, being a scientist, was just your dad’s job,” said Brunner.

Spanish Version: Un descubrimiento realizado hace 65 años en ORNL abrió camino a las vacunas contra COVID-19 a base de ARNm

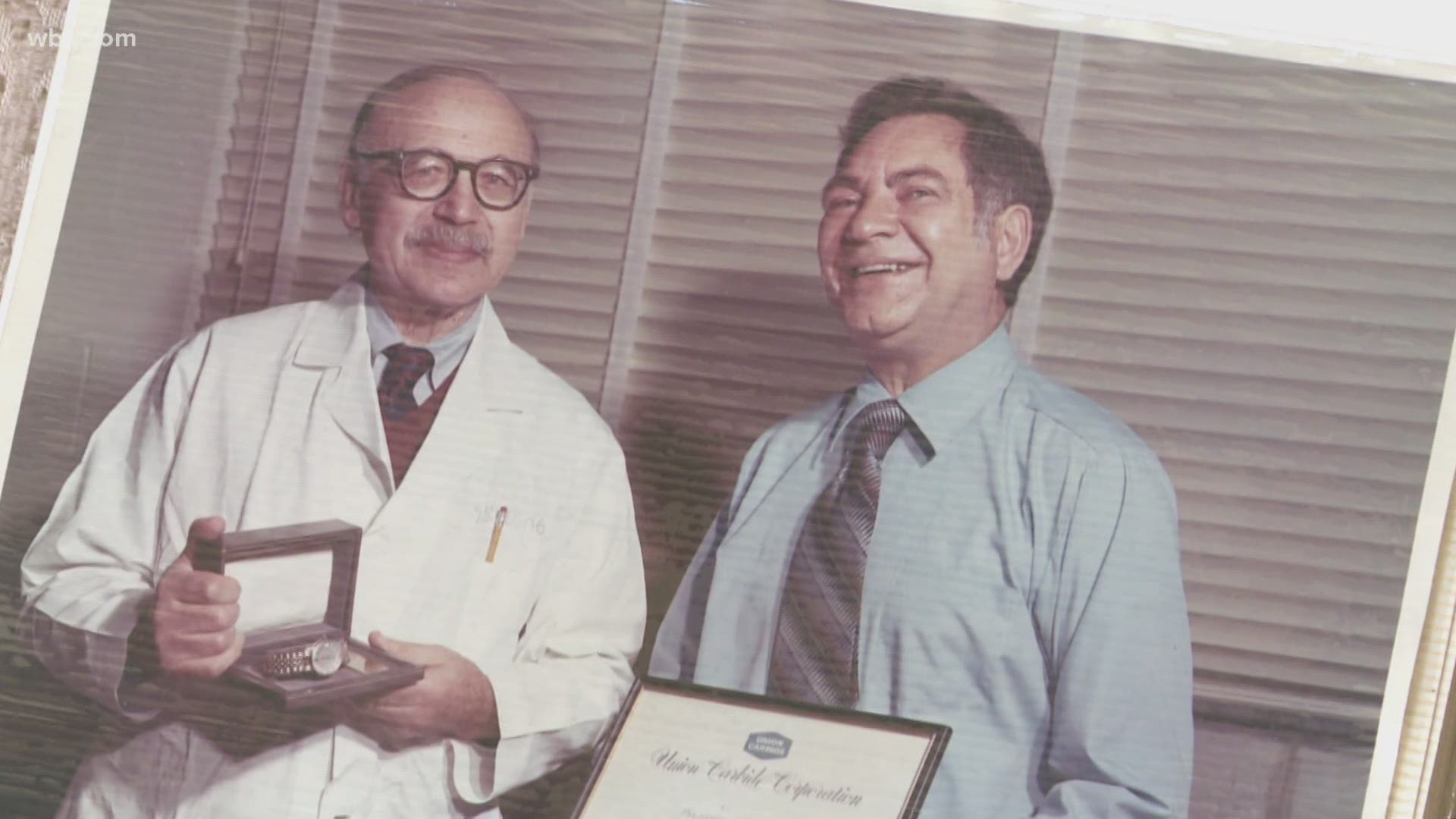

But his wasn’t your average, everyday job. In 1956, Volkin made a discovery at ORNL that was described by fellow scientists as one of the most important events in the history of molecular biology. Volkin and his research partner Lazarus Astrachan first observed and described what later came to be known as messenger RNA, mRNA.

Now, decades later, that messenger RNA has proven to be the building block of life saving and potentially pandemic-ending vaccines for COVID-19.

Elliot Volkin grew up in a small town near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He was the youngest of seven children born to Lithuanian immigrants. Science was his passion that lead him to study at Penn State University.

“The interesting thing was biochemistry was really not even much of a thing then as a field so he was in the College of Agriculture,” said Brunner.

Volkin graduated in 1942 and went on to graduate school at Duke University. There he met the love of his life, Sylvia. They married in 1948 and moved to Oak Ridge where he launched into his work at ORNL. In 1956, Volkin and Astrachan discovered mRNA. It made headlines in the world of molecular science. But at home in Oak Ridge, young Karen and her sister had no clue of their father’s seminal research.

“No idea…no idea whatsoever,“ said Brunner. “And as it became known how groundbreaking this was, the person who made me aware of how important this was and what my dad was doing that was so important was my mother.“

Despite their significant finding, Volkin and Astrachan’s identification of mRNA would, in time, be overshadowed. Three French researchers ultimately received credit and the 1965 Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology for discovering mRNA.

When asked about it years later, Volkin said. “I have no hard feelings. That’s the way things were.”

“You know, I’ll never know what was in his heart of hearts.” Said Brunner. I think he understood that’s how science works sometimes. Were it me, I probably would have felt cheated.”

Volkin had a long and distinguished career at ORNL. He died in 2011 at the age of 92, never to see how his mRNA research contributed to covid-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna. Those pharmaceutical companies employed mRNA technology to create the vaccines that are more than 90 percent effective at preventing the virus.

“You know, he was just my dad but to my friends and family, he was a giant. So as soon as the news about the vaccines came out my Facebook just blew up with classmates who were so excited about his,” said Brunner.

It was a moment of pride for Brunner when she got her first dose of Moderna. “I did say something to the health nurse giving it and she was like, ‘Wow, that’s pretty cool!’”

Alvin Weinberg, the long-time director of ORNL once said Volkin and Astrachan’s mRNA discovery never received the acclaim it deserved. But Karen Brunner says, for her father, it was never about the praise. It was always about the science and its purpose

“Understanding how science really impacts our lives for the better is something we all need to pay attention to. We can’t all be scientists but we all need to appreciate and honor them for the work they do.”