SEVIER COUNTY, Tennessee — Lots of folks enjoy pumpkin pie at Thanksgiving. But arguably no one gave more thanks for pumpkins than the famous Walker sisters of the Great Smoky Mountains.

The unmarried Walker sisters gained international fame in the 1940s for continuing to live an old-fashioned 19th-century lifestyle at their family cabin, even after the land became part of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP).

It's been more than 55 years since the death of Louisa Walker, the last sibling who remained at the log cabin built by their father in Little Greenbrier. The site of old cabin and the story of the devoted sisters continues to captivate millions of annual visitors to the Smokies.

Those who knew the Walker sisters claim they credited their entire existence to a favorite fall food.

"They loved pumpkins. They had beautiful pumpkin mounds and vines they kept not in the garden, but in the yard," said Robin Goddard, a longtime GSMNP volunteer and teacher.

Goddard grew up accompanying a neighbor and mentor, Elsie Burrell, on visits to Walker sisters.

"Miss Elsie was best friends with the Walker sisters. When we ate, we had to have flowers on the table. I went around and picked all these pumpkin blossoms and put them in a jar. I mean, Miss Elsie wore me out. If you don't have any blossoms, you don't have any pumpkins," said Goddard.

Although she learned about the significance of pumpkins to the Walker sisters the hard way, Goddard said she appreciated the lesson of why the squash held such sentimental value.

"Louisa used to say, 'We wouldn't be here if it wasn't for pumpkins.' Without pumpkins, their daddy would have died," said Goddard.

CIVIL WAR STALLS LOVE

The Walker sisters' reverence of pumpkins was rooted in the history of their father, John Walker.

In the 1860s, John Walker fell in love with a girl named Margaret King. But love had to wait with war tearing the nation apart.

Like most mountain people, John Walker ardently supported the United States of America and had no sympathy for the Confederacy.

"The Civil War broke out and he went and fought for the Union," said Goddard.

NPS historical reports claim Walker and other young mountain men made an elaborate plan to secretly meet in the night and make their way to Union forces. The report states, "At the proper time a signal bonfire was lit atop Bluff Mountain and the men gathered, marched north, and eventually enlisted in a Union military unit."

John Walker's headstone includes the inscription "First Tennessee Light Artillery Battalion," part of the Union Army.

Family oral tradition claimed John Walker fought in one battle before he was captured and held as a prisoner of war.

"He was put in Andersonville prison," said Goddard.

ANDERSONVILLE ATROCITIES

The stockade and cemetery in Andersonville, Georgia, now stand as a national historic site for many reasons.

Camp Sumter in Andersonville was no ordinary prison. It was the worst of the worst for captured Union troops. The infamous site was an overcrowded and disease-ridden swamp without enough food, water, or sanitation for prisoners.

Of the roughly 45,000 Union troops sent to Andersonville in the final 14 months of the Civil War, nearly 13,000 of them died in prison. The few photographs and many drawings of the prison by inmates show scenes associated today with the images of starving prisoners in concentration camps during World War II.

John Walker lost 100 pounds while imprisoned at Andersonville. His family often recalled the story of how he was saved from starvation by a sympathetic farmer.

"He almost died. An old farmer that lived on the outside threw pieces of pumpkin over the fence because he felt sorry for the prisoners. They were starving to death," said Goddard.

NPS records tell a similar version of the story, but the details vary for how the pumpkins reached Walker. The record reads, "He told his children of starvation and ill-treatment while a prisoner, but he also told them of a sympathetic southern farmer who eased his hunger pangs when he dumped a wagon load of pumpkins into the prison compound."

John Walker found enough nourishment from the pulp the rind of pumpkins to hang onto life until he was released in a prisoner exchange.

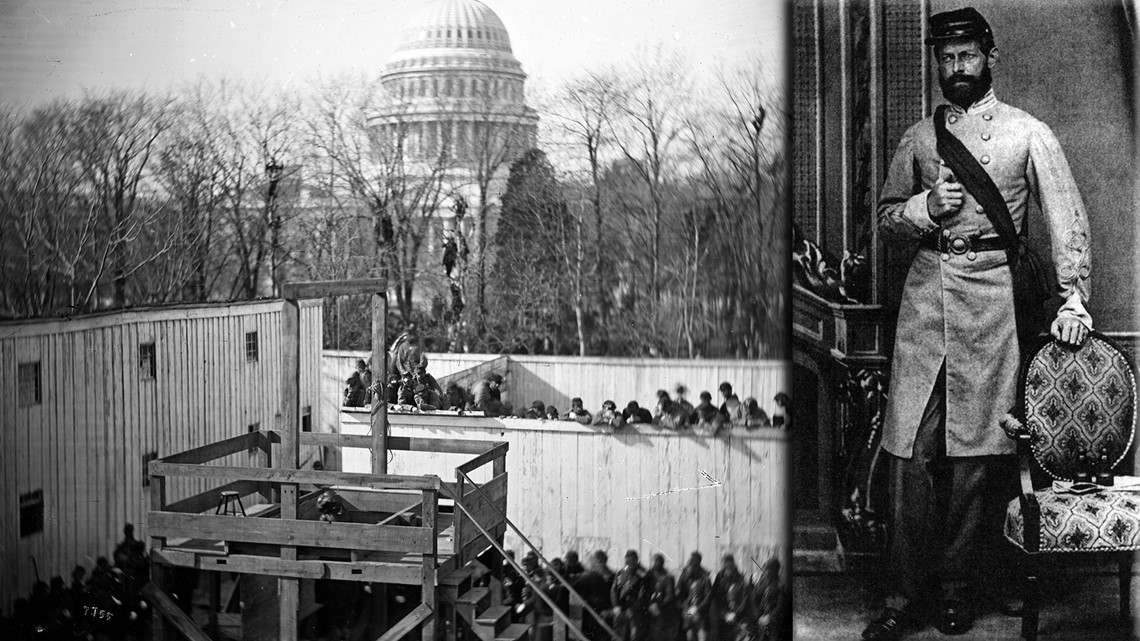

When the war ended, the Confederate officer in charge of the cruel prison in Andersonville was convicted of war crimes and executed. Captain Henry Wirz was hanged Nov. 10, 1865, in Washington, D.C.

Wirz is one of only two people convicted of war crimes during the Civil War.

SPROUTING WALKER FAMILY TRADITION

When the war ended, John Walker returned to Tennessee, married Margaret King, had 11 children, and built a sizeable addition to an old cabin that still stands today.

Along with his prized apples and cherries, Walker's family made sure to grow the sentimental squash that saved him from starvation.

"Pumpkins were very important to the Walker sisters. Very," said Goddard.

While the most famous members of the Walker family are the sisters who did not marry, one of the daughters and four sons started families of their own. Some relatives continue to cherish pumpkins.

"That tradition carried on because there is great-nephew now who raises pumpkins, and they're beautiful," said Goddard.

While many people enjoy the pumpkin harvest for decoration and delicious food during the fall, the Walker family had special reason to give thanks for pumpkins. The plant is why we have a Walker family tree and their captivating history in the Great Smoky Mountains.

WALKER SISTERS SERIES

Below are links to WBIR's full three-part series on the Walker sisters from May 2019. The final link takes you to an interactive tool where you can drag a slider to compare historic photos of the Walker sisters to current photos from the same angle.