Reporter's note: this is the first article in a three-part series on the Walker sisters. See these links for the full series.

(GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS) It has been 55 years since Louisa Walker died. She was the last of a famous group of siblings who lived and died at a log cabin built by their father in the Great Smoky Mountains.

The Walker family had four boys and seven daughters. All but one of the daughters remained at the old cabin near Little Greenbrier their entire lives. They chose an old-fashioned 19th century lifestyle they learned from their parents. They made their own clothes, grew their own food, and lived long lives without the comforts of indoor plumbing or electricity.

When their farm was consumed by a new national park in the 1930s and 1940s, they found a way to remain at their family home until they died several decades later.

In this three-part series, we look at the fascinating lives of the Walker sisters before the creation of the national park, what it was like to live inside a national park as a tourist attraction, and how their preserved legacy continues to fascinate countless visitors to Smokies.

PART ONE: LIFE BEFORE THE PARK

Robin Goddard loads up her car with artifacts and then unpacks history every week at the one-room Little Greenbrier School in the Smokies. The 50-year volunteer even dresses the part as she teaches people about life in the days long before this became a national park.

"I'm wearing a dress like they wore in the 1800s. I love sharing the history," said Goddard. "We go through the spelling chart. I show them the children's toys. It is just a lot of fun."

Goddard also teaches a popular subject she learned all about as a child.

"I love sharing the stories of the Walker sisters. I grew up with them. They have quite a following. A neighbor of mine growing up, Miss Elsie Burrell, was a school supervisor and best friends with the Walker sisters. Miss Elsie Burrell took me with her [to the Walkers] from the time I was four years old until I graduated from high school. Working, working, and working," said Goddard with a bitter grin.

There was plenty of work to be done helping a group of sisters famous for living like their ancestors in the 1800s as they refused to leave their family home even after the area became a national park in the 1930s and 1940s.

"They were proud of their land. The connection went back many generations. Their father, John Walker, moved to this area before the Civil War, fell in love with his wife whose family owned this cabin. He went off to fight for the Union when the war broke out and barely survived as a prisoner of war at Andersonville. When the war was over, he came back here to Little Greenbrier and was the patriarch of the community. He said we need a school, we need a church, and the community came together to build it," said Goddard.

John Walker built a two-story addition to what was previously a one-room cabin. A porch was also added with doors to the two sections.

John Walker then built a family of 11 children consisting of four boys and seven girls.

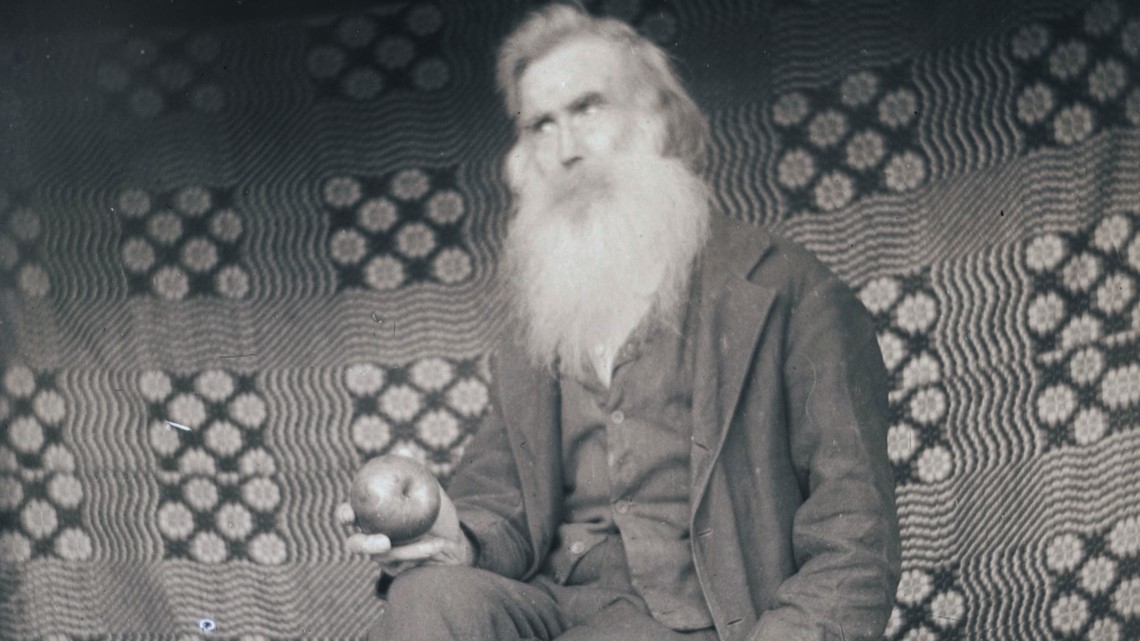

"It was very crowded and you had to learn to get along. They were self-sustaining farmers. They had big gardens. He had big apple orchards. And any time you see pictures of [John Walker], you see apples or cherries with him," said Goddard.

The fruits of John Walker's labor include building the Little Greenbrier school where his children learned to read, write, and arithmetic. His sons took their education out into the world and started their own families. But almost all of his daughters applied their teachings to the homestead for the rest of their lives.

"Of all the daughters, Margaret is the oldest. She ruled the roost. She told you what to do and when to do it. And you did it," said Goddard. "She presented this demeanor about her that they [the sisters] had to take care of their home. She was going to take care of it the rest of her life and 'if you go out and get married, who is going to help me take care of it?' There won't be anybody here to do it because all the brothers had already married."

The second daughter went by the name Polly and was known as an excellent cook. Martha was the third daughter and was the accountant of the family, tracking finances and supplies.

"Martha was quiet. She didn't say much. But when she did speak, people listened," said Goddard. "The fourth daughter was Nancy Melinda. Nancy, I did not know. She died in 1931 before this became a national park."

The fifth daughter, Louisa, was likely one of the most well-remembered because she was both friendly and the last resident at the cabin to die.

"Louisa was my favorite. She loved to laugh and she loved funny things. Louisa is the one that wrote all the poetry. And her name is pronounced loo-eye-zuh," said Goddard.

The sixth daughter was the only to marry and move out of the house. Caroline fell in love with Jim Shelton, a man who worked on the Walker farm and took some of the earliest and best photographs of the Walker family and the entire region in the Smokies

"The last daughter was Hettie Rebecca. Hettie was great at knitting and doing needlework. She was perfected in it," said Goddard. "You had seven girls and only one of them married at a time when the marrying age for girls in the mountains was 14 years old."

Caroline wasn't the only sister to discover love. Both Polly and Martha were engaged to men who worked for the lumber company that built railroads and harvested trees from the Smokies. Both fiancés died in separate work-related train accidents.

"Martha had her mourning time and was able to move on, but Polly had a hard time getting over it. The sisters used to say, 'Poor sister Polly. She died of a broken heart.' She had a lot of trouble with it until the day she died," said Goddard.

The Walker sisters lost other loved ones at a time when discussion of a new national park was gaining momentum. Their father, John Walker, died in 1921. Ten years later, sister Nancy in 1931.

Five sisters remained at the cabin and were married to the land in the early 1930s. That's when the State of Tennessee came courting with a proposal to buy their property and donate it to a new national park.

"They were not happy. No government is going to get their land. And they were not about ready to sell. They were born there, their ancestors were born there, and they were proud of it," said Goddard.

As the states of Tennessee and North Carolina continued acquiring enough land for the federal government to authorize a national park, the Walker sisters continued to refuse to sell, even with an lifetime lease offer to remain on their property until death.

Ultimately, time ran out. The park was officially dedicated in 1940 and in 1941 their 122 acres were condemned. The deed was given to the National Park Service.

"The mood that I saw all the time was this was our home and we don't want to leave," said Goddard.

SERIES LINKS