OAK RIDGE, Tenn. — Hours after the United States dropped the bomb dubbed "Little Boy," President Harry Truman issued a chilling warning to Japan and the world.

"With this bomb we have now added a new and revolutionary increase in destruction to supplement the growing power of our armed forces. In their present form these bombs are now in production and even more powerful forms are in development," his White House statement declared Aug. 6, 1945.

If Japan didn't surrender immediately, Truman said, it faced a "rain of ruin" from the sky.

It took a second bomb, this one on Aug. 9, 1945, on the port city of Nagasaki, but Japan finally buckled. War in the Pacific was over.

This week marks the 75th anniversary of the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan. The United States is the only nation to use the weapon in a war.

It's an event that resonates to this day in Tennessee because of the historic role Oak Ridge played in the bomb's development. It's a moment that changed the course of human history. It's a decision that's still being debated across the globe.

Peace groups will gather this week in Oak Ridge and around the world to remember the swift devastation of the atomic bombings and their uneasy legacy.

Fueled by the Secret City

Truman, in his White House announcement back in 1945, said the United States had harnessed "the basic power of the universe."

Historians attribute a warning by physicist Albert Einstein to the U.S. push to build the bomb -- with Oak Ridge at its hub.

If America wasn't careful, Einstein said in an August 1939 letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Adolf Hitler's Germany could very well create its own nuclear bomb that would threaten all of Western civilization.

The Germans would soon be on the move to take over Europe.

"In the course of the last four months it has been made probable ... that it may become possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium, by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium-like elements would be generated. Now it appears almost certain that this could be achieved in the immediate future," the scientist's letter stated.

Roosevelt listened to Einstein, and he acted.

With the help of Tennessee Sen. Kenneth McKellar, chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, the wartime president quietly began budgeting millions of dollars to cover the effort that would come to be known as the Manhattan Project. It was named for the New York borough where some of the first organizational work began.

By 1943, the government had acquired thousands and thousands of rural East Tennessee acres that would eventually become known as Oak Ridge -- all part of a national race to harvest enough bomb-making material to bring a decisive end to World War II.

Some work into nuclear science was already going on at U.S. universities such as the University of Chicago and Columbia University. With Roosevelt's approval, the government stepped in to take charge.

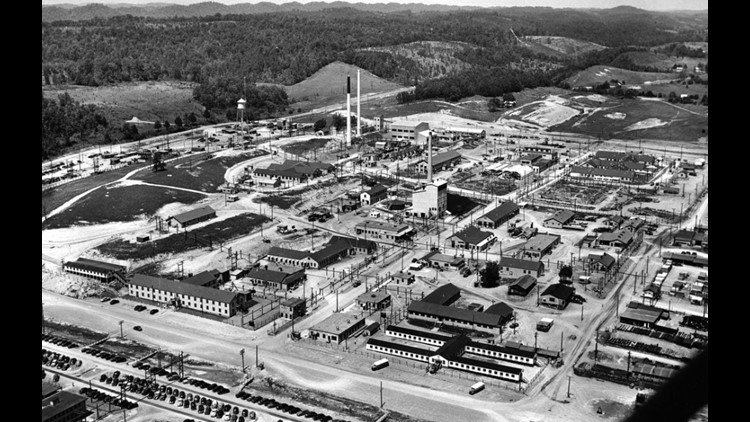

It was a massive undertaking conducted in absolute secrecy. Some 59,000 acres were assembled rapidly in what was then called Bear Creek Valley about 25 miles west of Knoxville. The government bought out some families and ordered them off the land in a matter of weeks.

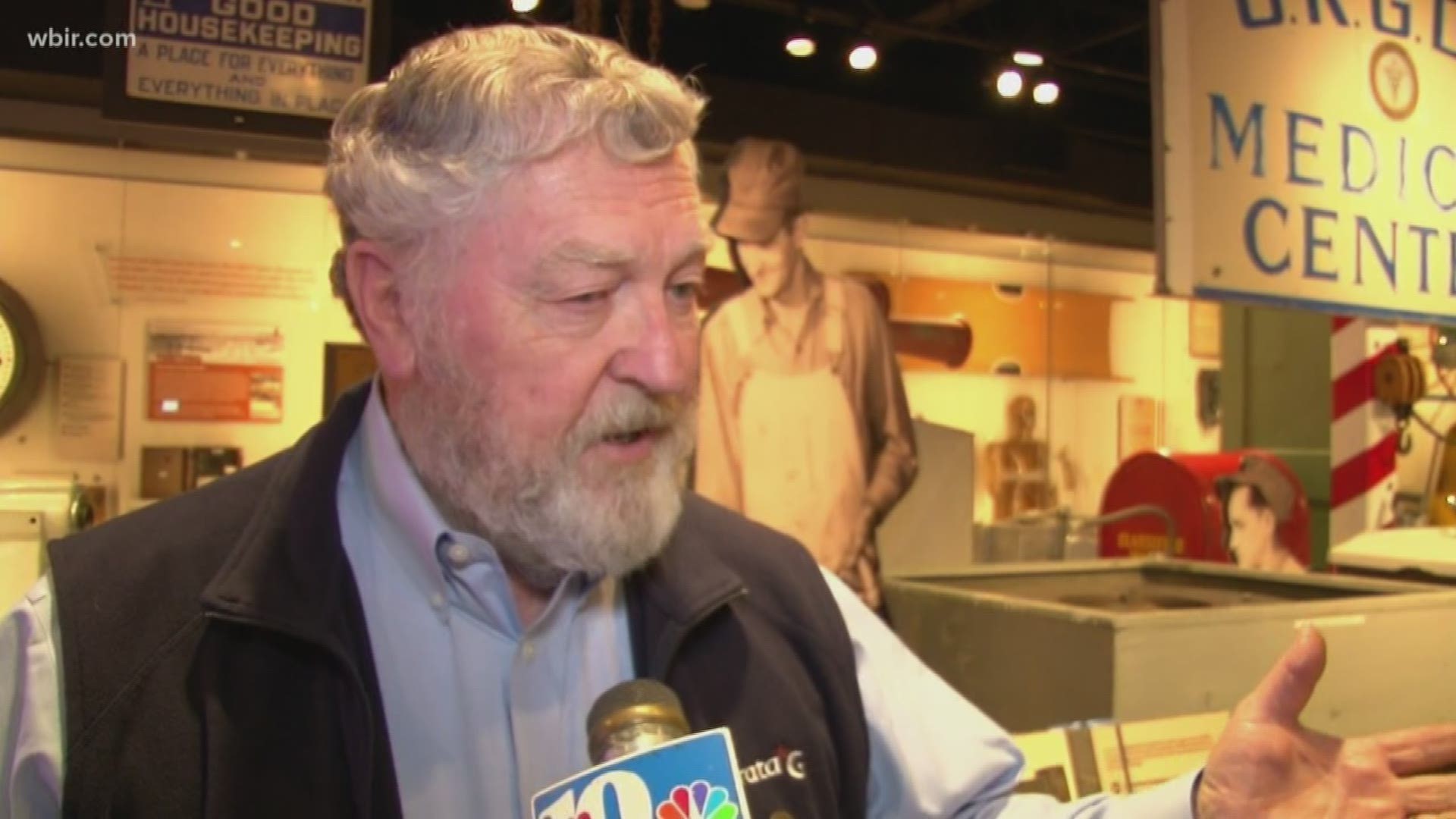

Almost everyone had a can-do approach, said Ray Smith, Oak Ridge reservation historian.

"That was the mentality back then. 'We want to help win the war.' So everyone was looking for what they can do," Smith said.

The region's many ridges and multiple valleys served as an excellent place to conduct operations. The Tennessee Valley Authority provided bountiful power from sites such as the new Norris Dam.

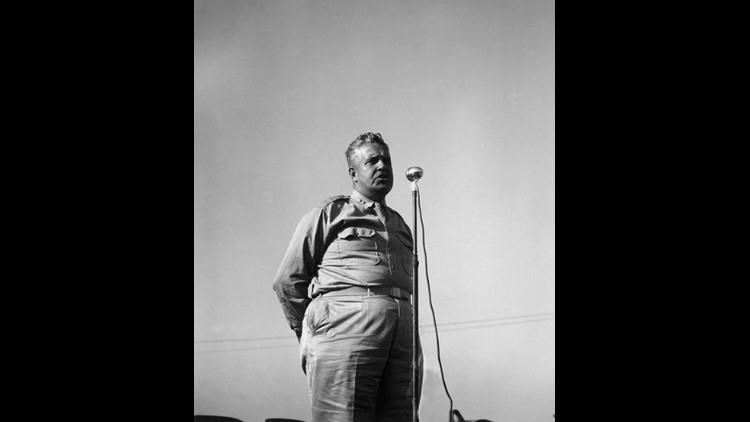

Hard-charging Gen. Leslie Groves, of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who had just finished overseeing construction of the massive Pentagon, was tapped to build the plants that would hopefully harness this new nuclear power source.

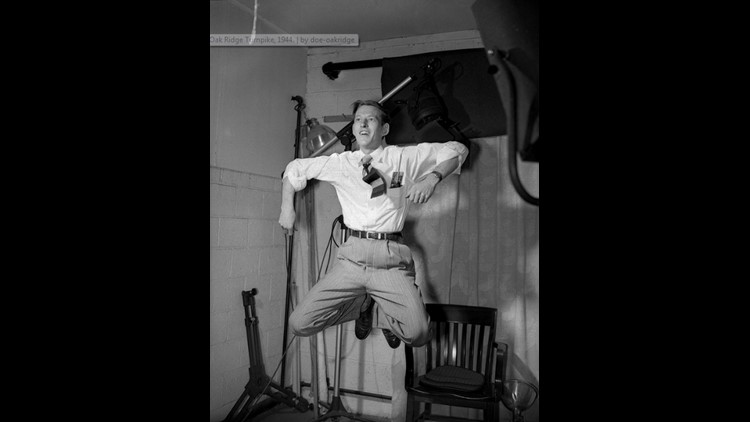

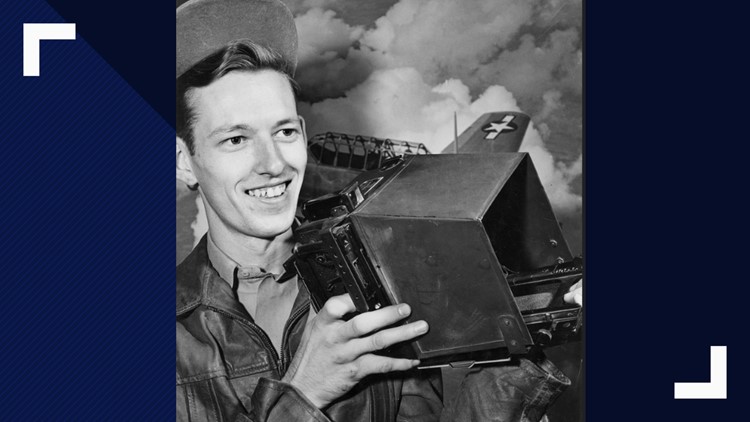

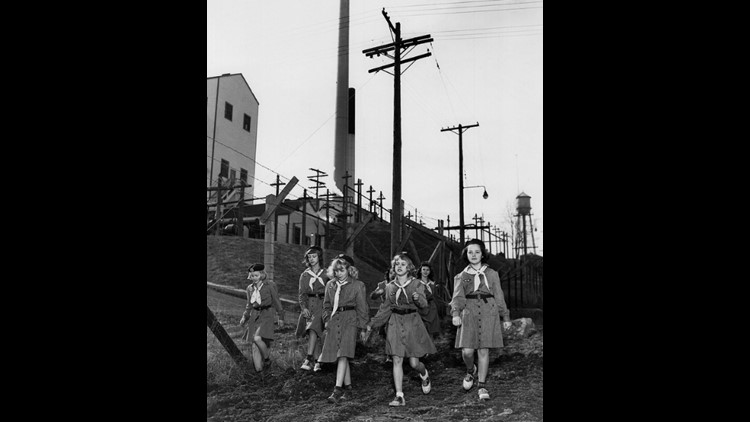

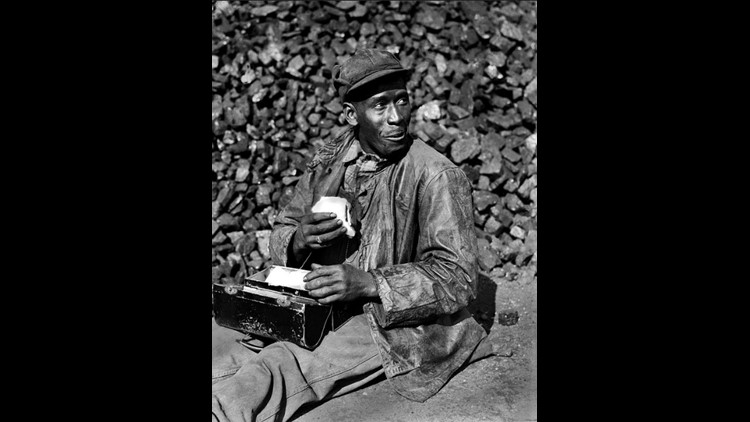

Documenting the Manhattan Project: The photos of Ed Westcott

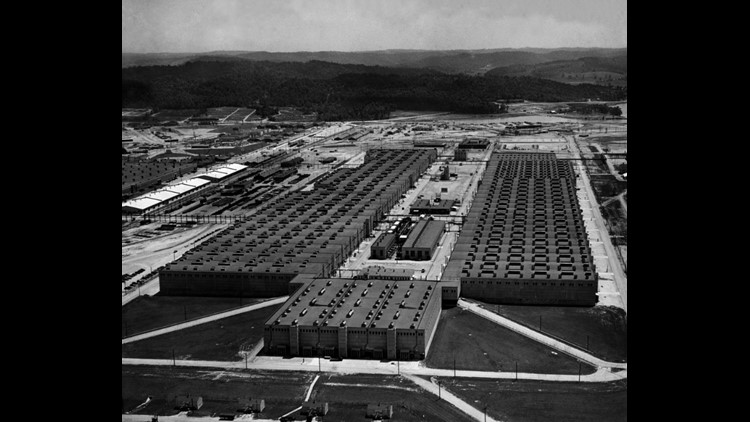

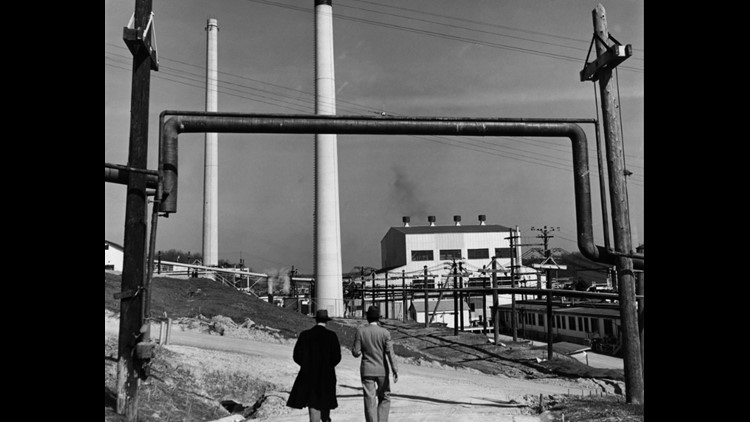

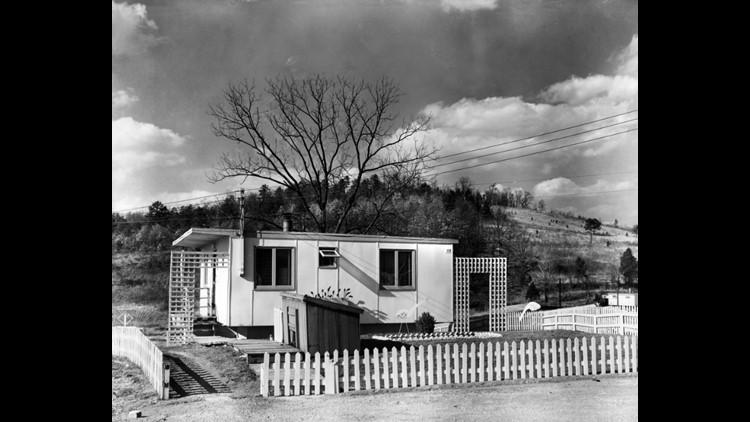

Buildings began going up immediately in 1943: an administrative complex, a graphite reactor to try to harvest bomb-making material; pre-fab housing for thousands of workers who would be needed in the effort; and later the 44-acre K-25 plant that would use a process called gaseous diffusion as another means of collecting weapons fuel.

X-10, where the reactor was located, and Y-12, site of an electromagnetic separate plant, were two key areas of the reservation.

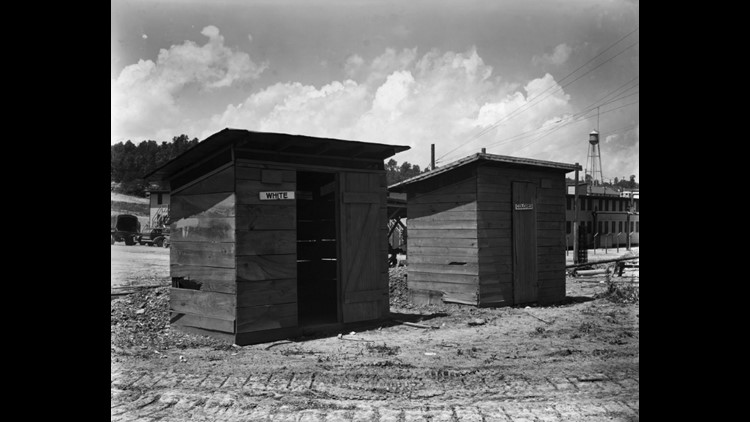

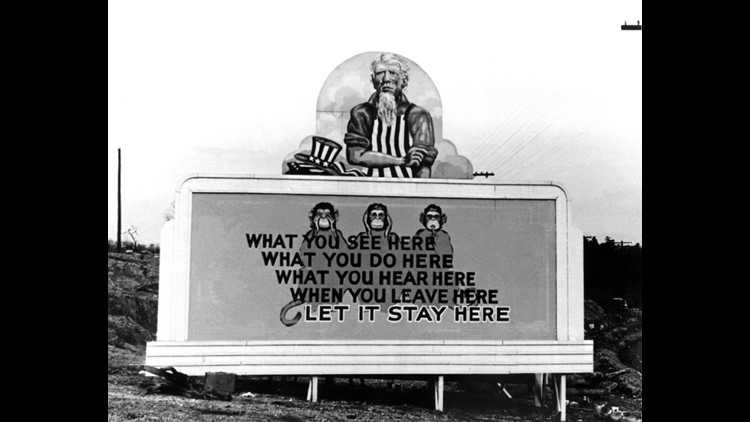

Few workers understood exactly what they were doing. They just knew it was part of the effort to win the war. Workers often were segregated and prohibited from revealing what they were doing, even to other employees.

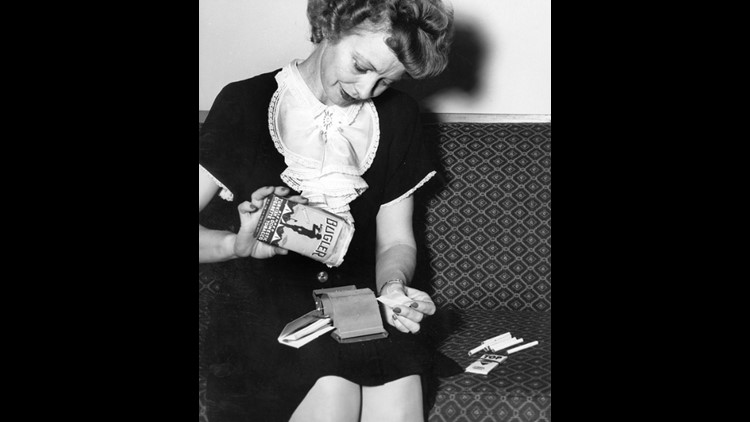

"You were going to do this job, and you know nothing, and you don't know the product, and you don't know what's inside your cubicle," said Lois Gatlin, who as a young woman worked at Y-12.

Work went on 24 hours a day. Construction never stopped. If you stepped away in the morning, new buildings likely had gone up by the time you came back at night.

All that constant construction could be messy and chaotic. Mud seemed a constant presence on the grounds.

"This was a rural town," recalled the late Cecilia Klemski, who worked as a secretary for plant administrators. "There was nothing here when I came, you know. So I wouldn’t step in that mud, so the cab driver carried me inside."

Security was tight. Warning signs dotted the landscape. Sometimes if a worker said too much and authorities found out about it, they'd be gone the next day, dismissed from the reservation.

Sometimes, operations suffered setbacks. Machinery didn't work like it was supposed to. Progress wasn't always smooth. But Groves pressed on.

By 1944, scientists had successfully shown they could gather the material that would produce a bomb. Work to make bomb materials also went on at a plant in Hanford, Wash.

Bombs bring war to a close

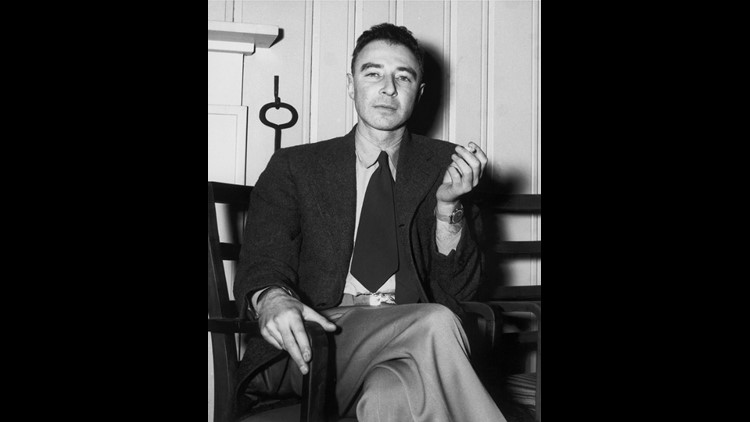

The focus shifted to the remote desert of Los Alamos, N.M., where the actual bombs were built. In July 1945 the first successful test of a nuclear explosion was staged there under the code name Trinity.

Roosevelt had died in April 1945 and Germany had surrendered in May 1945, but the new president, Harry S. Truman, ensured that work continued on the bomb to end the war with Japan in the Pacific.

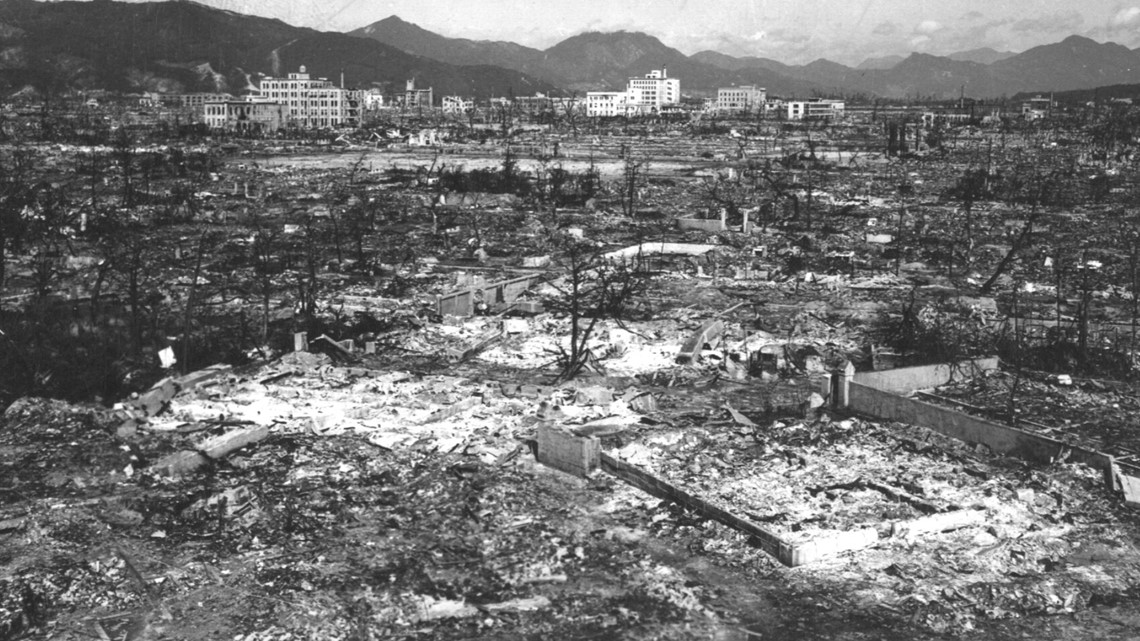

When Truman's "rain of ruin" hit Japan, the results were devastating. The temperature near the blast site reached 5,400 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the National Park Service.

More than 129,000 and perhaps as many as 225,000 Japanese died in the blasts. Most were civilians.

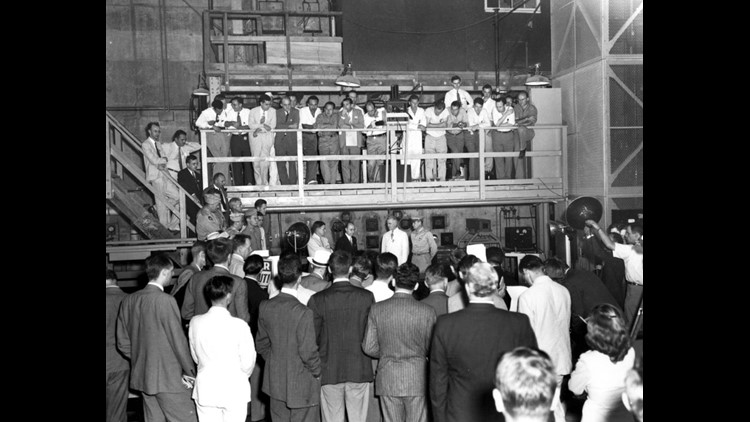

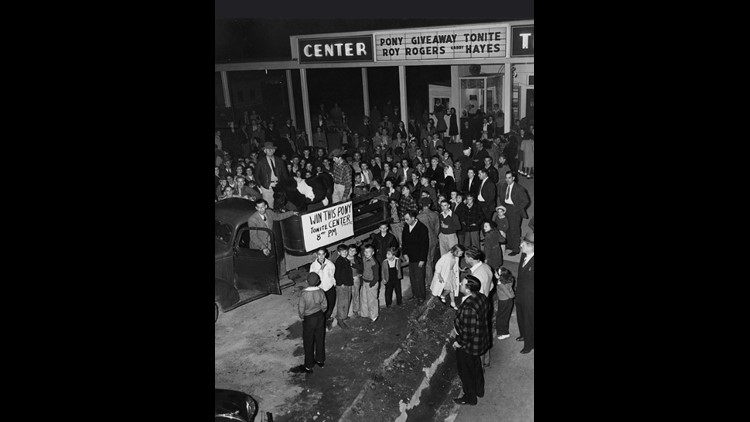

On Aug. 15, 1945, word went out across America that Emperor Hirohito had announced a surrender. Jubilation spread across the Oak Ridge reservation.

Klemski remembered it vividly.

"I couldn’t go to that celebration and I wanted to, but of course all my other friends that did go were telling me how wonderful it was. It was just an exciting time," she said.

But it was sobering, too. For now everyone knew what they'd been doing in the war effort. They'd been helping to build a weapon the likes of which never had been seen before, a catastrophic device that completely altered how nations would think about waging war.

The Secret City was a secret no more.

Legacy of the bomb

Oak Ridge helped win World War II. It also secured a permanent place for itself in the U.S. strategy to maintain nuclear weapons.

In August 1949, just four years after World War II ended, the Soviets staged the first of what would be scores of nuclear tests.

America and its allies saw a new threat with nuclear technology at the center. An arms race ensued.

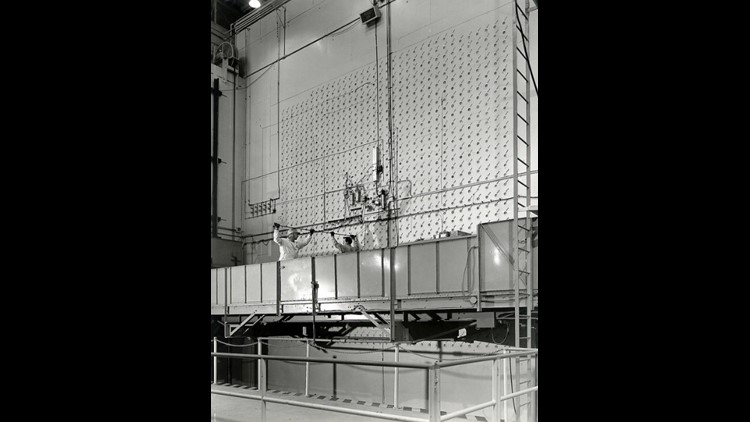

In the early 1950s, the U.S. government staged more than 60 nuclear weapons tests. According to the federal Department of Energy, Y-12 provided nuclear components for them all. Going forward, Y-12's main task was to make and maintain nuclear weapons components.

Today's Y-12 maintains the U.S. nuclear stockpile and disassembles the nuclear material of other nations. Work is ongoing at Y-12 on the biggest construction project in the state, the Uranium Processing Facility, or UPF.

The multi-building UPF will support the national nuclear weapons stockpile, defense nuclear nonproliferation and naval reactors, according to Y-12. It's supposed to be done by 2025 at a maximum cost of $6.5 billion.

Debate continues today on whether it's right for America to maintain nuclear weapons.

In July 2012, three people including a New York-born Catholic nun in her 80s broke into the Y-12 grounds and threw human blood on what was supposed to be a heavily guarded uranium processing building. The New York Times reported it as the "biggest security breach in the history of the nation's atomic complex."

Today, the U.S. and Japan are staunch allies. Visitors can see proof of that at A.K. Bissell Park, where the Oak Ridge International Friendship Bell is on display. The multi-national project was dedicated 24 years ago to symbolize "the strides for peace and reconciliation between Japan and the United States," according to the Atomic Heritage Foundation.