Oak Ridge — A dire warning from an eminent scientist sparked the creation of Oak Ridge.

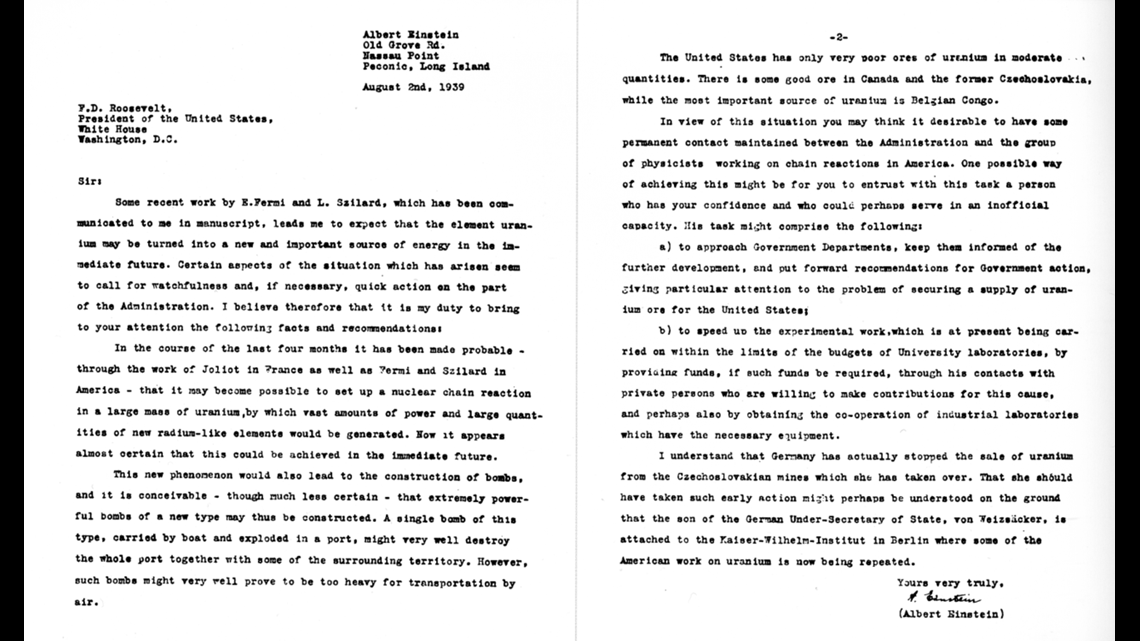

"In the course of the last four months it has been made probable ... that it may become possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium, by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium-like elements would be generated. Now it appears almost certain that this could be achieved in the immediate future."

If America wasn't careful, Albert Einstein went on in his 1939 letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Adolf Hitler's Germany could very well create its own nuclear bomb that would threaten all of Western civilization.

Roosevelt listened to Einstein, and he acted.

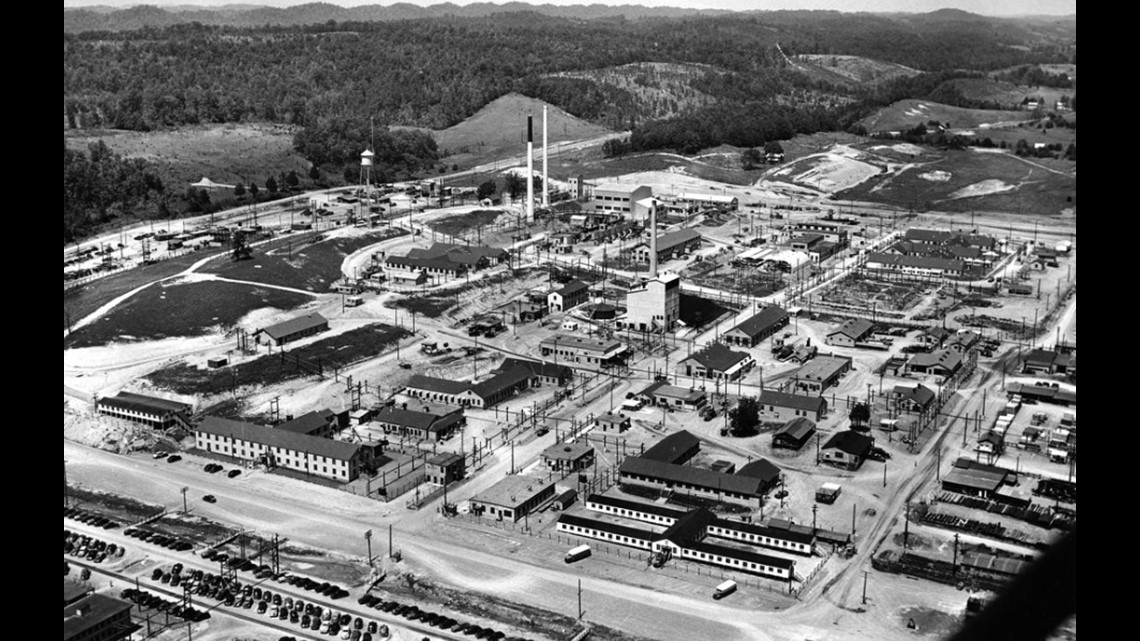

By 1943, the government had acquired thousands and thousands of rural East Tennessee acres that would eventually become known as Oak Ridge -- all part of a national race to harvest enough bomb-making material to bring a decisive end to World War II.

This year, across the federal reservation and in Oak Ridge, scientists, historians and local leaders are observing the 75th anniversary of the founding of the federal facilities. Work at the plants known as X-10, Y-12 and K-25 changed the course of history, not just for the United States but for mankind itself.

Scientists and researchers in Oak Ridge continue to explore new developments -- in biology, transportation, physics, supercomputing, climatology and composite materials.

Today, Oak Ridge National Laboratory is one of the leading science think-tanks and testing grounds in the world. Y-12 stores the nation's uranium, disassembles the nuclear material of other nations and maintains the U.S. nuclear stockpile.

“There is probably not a single person anywhere on this God-given Earth that is not impacted by Oak Ridge National Laboratory," said Thomas Zacharia, a longtime lab principal who in July 2017 became its director.

Said Bill Tindal, Y-12 site manager: "We're a safe place because of the hands and hearts and minds of East Tennesseans. We don't talk about it in that frame, but I feel that deeply -- that it is that we have a contribution here - that few areas in the country can claim."

Urgent, top secret mission

German scientists were already nosing around the idea of atomic power in the late 1930s. Several researchers in America knew that and realized as Hitler marched across Europe that he could pose a very real threat to the future of the world.

Some work into nuclear science was already going on at U.S. universities such as the University of Chicago and Columbia University. With Roosevelt's approval, the government stepped in to take charge.

Roosevelt, with the help of Tennessee Sen. Kenneth McKellar, chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, quietly began budgeting millions of dollars to cover the effort that would come to be known as the Manhattan Project. It was named for the New York borough where some of the first organizational work began.

It was a massive undertaking conducted in absolute secrecy. Some 59,000 acres were assembled rapidly in what was then called Bear Creek Valley about 25 miles west of Knoxville. The government bought out some families and ordered them off in a matter of weeks.

Almost everyone had a can-do approach, said Ray Smith, Oak Ridge reservation historian.

"That was the mentality back then. 'We want to help win the war.' So everyone was looking for what they can do," Smith said.

The region's many ridges and multiple valleys served as an excellent place to conduct operations. The Tennessee Valley Authority provided bountiful power from sites such as the new Norris Dam.

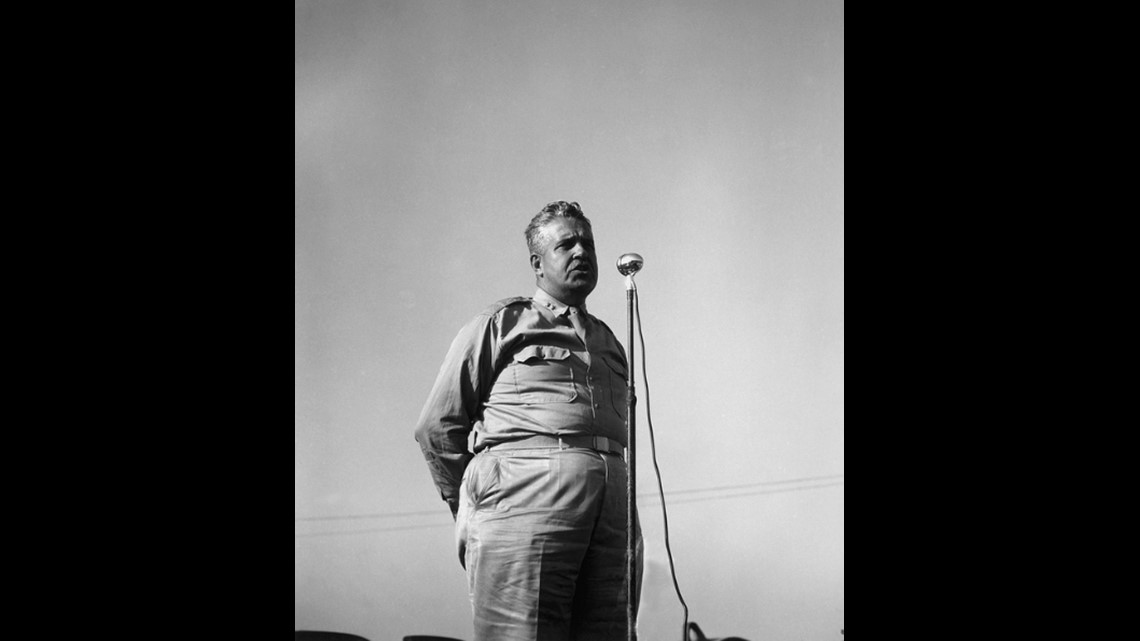

Hard-charging Gen. Leslie Groves, of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who had just finished overseeing construction of the massive Pentagon, was tapped to build the plants that would hopefully harness this new nuclear power source.

Buildings began going up immediately in 1943: an administrative complex, a graphite reactor to try to harvest bomb-making material; pre-fab housing for thousands of workers who would be needed in the effort; and later the 44-acre K-25 plant that would use a process called gaseous diffusion as another means of collecting weapons fuel.

X-10, where the reactor was located, and Y-12, site of an electromagnetic separate plant, were two key areas of the reservation.

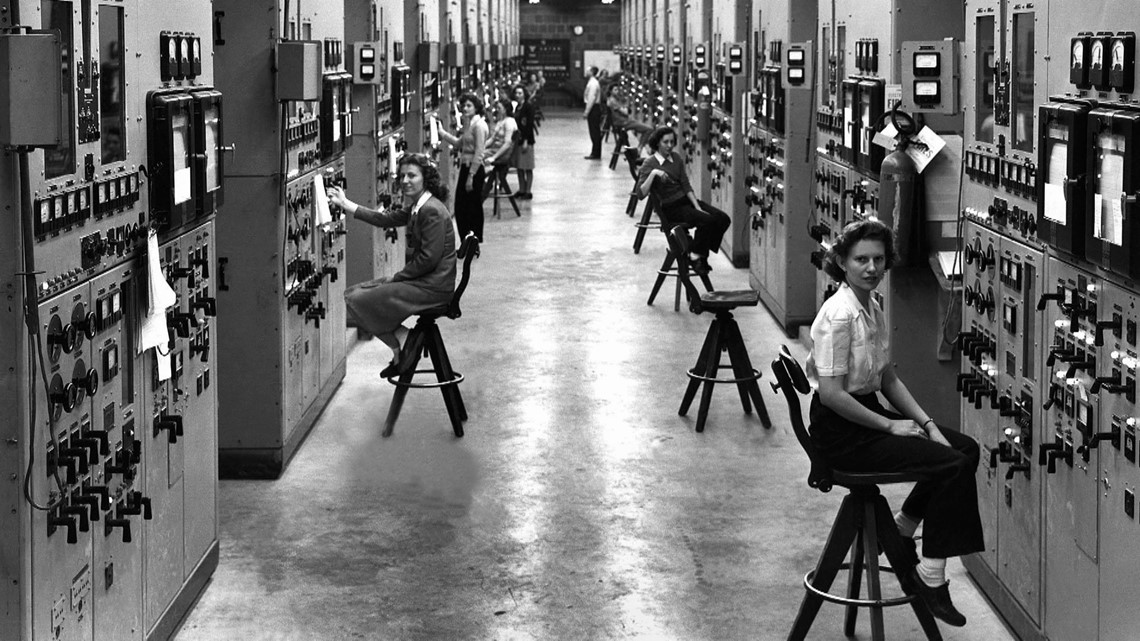

Few workers understood exactly what they were doing. They just knew it was part of the effort to win the war. Workers often were segregated and prohibited from revealing what they were doing, even to other employees.

"You were going to do this job, and you know nothing, and you don't know the product, and you don't know what's inside your cubicle," said Lois Gatlin, who as a young woman worked at Y-12.

Work went on 24 hours a day. Construction never stopped. If you stepped away in the morning, new buildings likely had gone up by the time you came back at night.

All that constant construction could be messy and chaotic. Mud seemed a constant presence on the grounds.

"This was a rural town," recalled the late Cecilia Klemski, who worked as a secretary for plant administrators. "There was nothing here when I came, you know. So I wouldn’t step in that mud, so the cab driver carried me inside."

Security was tight. Warning signs dotted the landscape. Sometimes if a worker said too much and authorities found out about it, they'd be gone the next day, dismissed from the reservation.

Sometimes, operations suffered setbacks. Machinery didn't work like it was supposed to. Progress wasn't always smooth. But Groves pressed on.

By 1944, scientists had successfully shown they could gather the material that would produce a bomb. Work to make bomb materials also went on at a plant in Hanford, Wash.

The focus shifted to the remote desert of Los Alamos, N.M., where the actual bombs were built. In July 1945 the first successful test of a nuclear explosion was staged there under the code name Trinity.

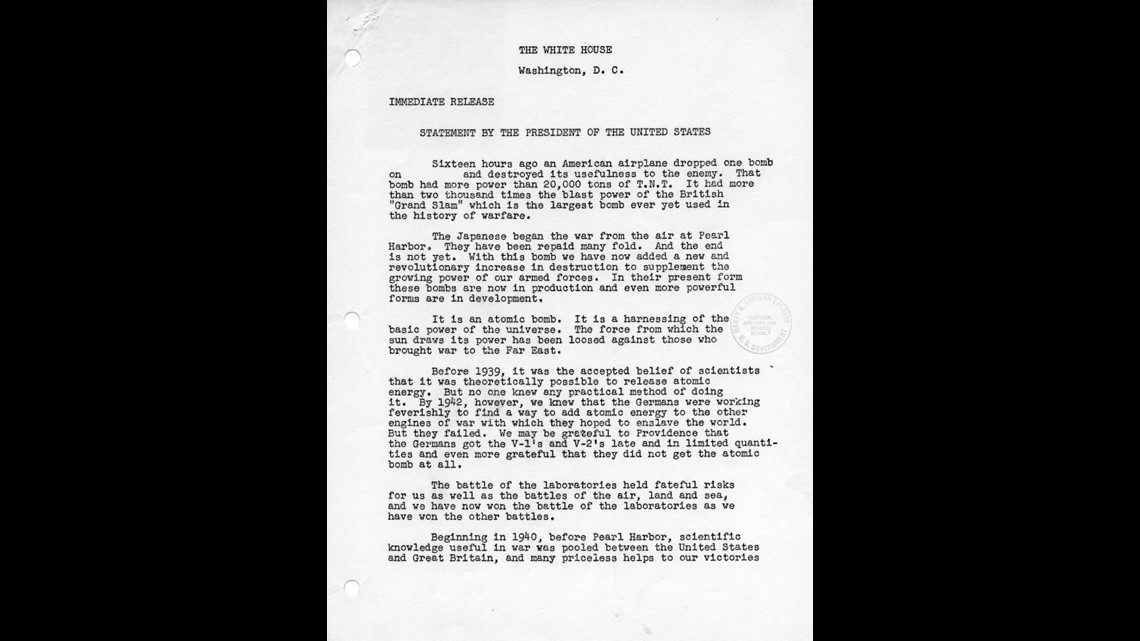

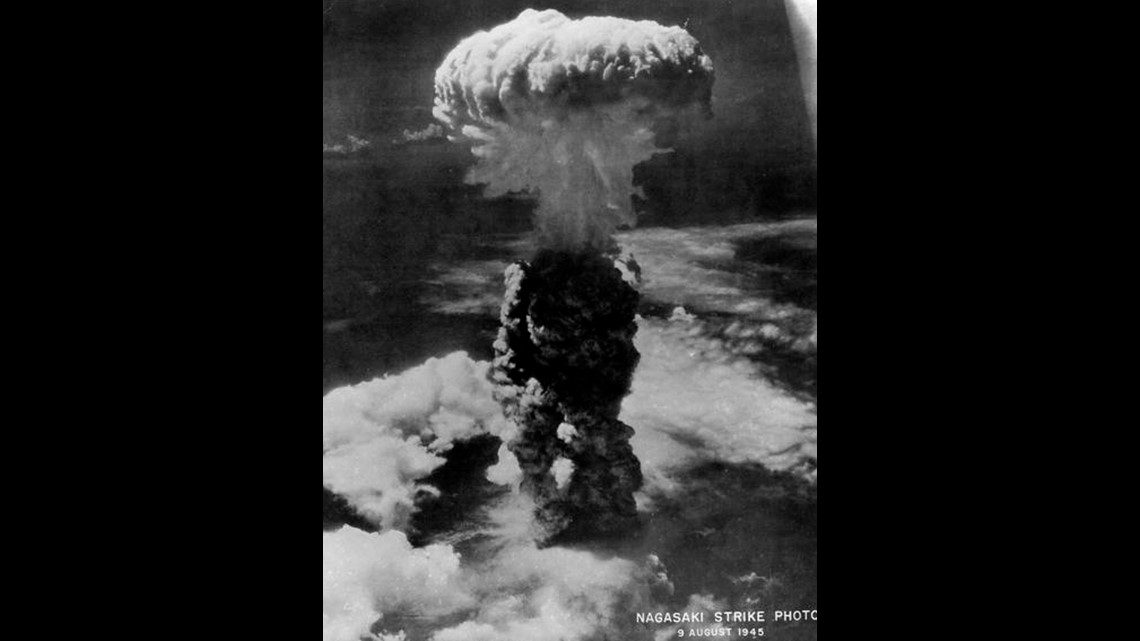

Roosevelt had died in April 1945 and Germany had surrendered in May 1945, but the new president, Harry S. Truman, ensured that work continued on the bomb to end the war with Japan in the Pacific.

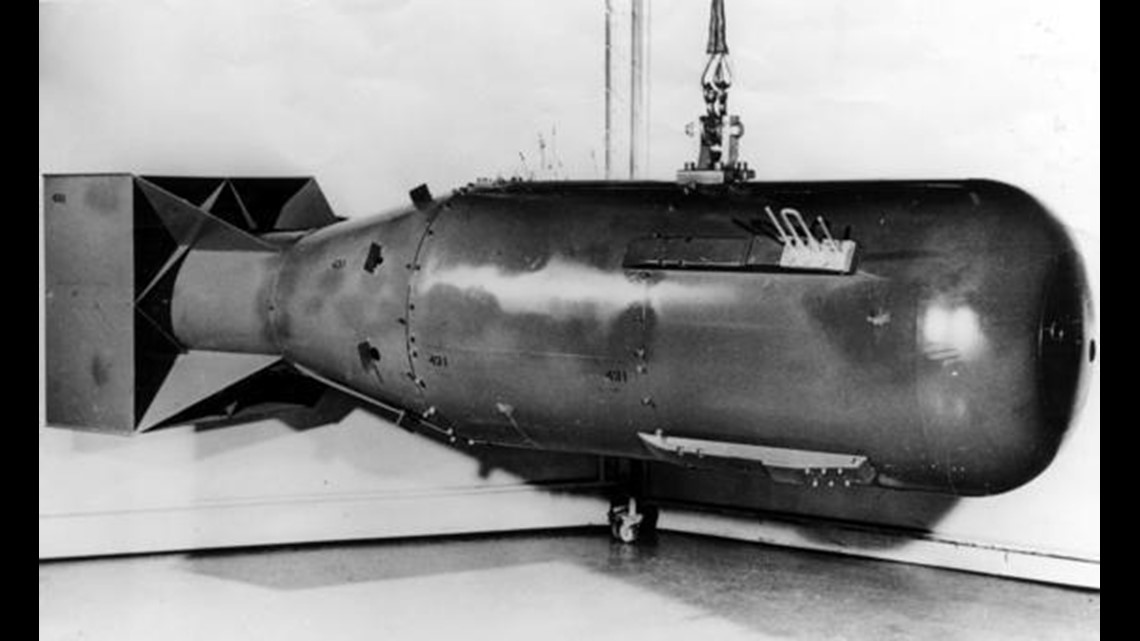

In August 1945, U.S. crews dropped two atomic bombs in Japan. The first, nicknamed Little Boy, hit Hiroshima on Aug. 6. The next, called Fat Man, came three days later.

The results were devastating. More than 129,000 and perhaps as many as 225,000 Japanese died in the blasts. Most were civilians.

On Aug. 15, word went out across America that Japan had surrendered. Jubilation spread across the reservation.

Klemski remembered it vividly.

"I couldn’t go to that celebration and I wanted to, but of course all my other friends that did go were telling me how wonderful it was. It was just an exciting time," she said.

But it was sobering, too. For now everyone knew what they'd been doing in the war effort. They'd been helping to build a weapon the likes of which never had been seen before, a catastrophic device that completely altered how nations would think about waging war.

The Secret City was a secret no more.

Exploring new worlds

Oak Ridge had helped win the war. But its role in nuclear research and nuclear bombs was far from over. The town that formally emerged after World War II and the federal reservation ended up playing a key role in a new kind of conflict -- what came to be known as the Cold War.

While the Germans and Japanese had been defeated, the end of World War II saw the emergence of the Soviet Union, a communist adversary to the West.

In August 1949, just four years after World War II ended, the Soviets staged the first of what would be scores of nuclear tests over the next 40 years.

America and its allies saw a new threat with nuclear technology at the center. An arms race ensued.

In the early 1950s, the U.S. government staged more than 60 nuclear weapons tests. According to the federal Department of Energy, Y-12 provided nuclear components for them all. Going forward, Y-12's main task was to make and maintain nuclear weapons components.

To the south, science also carried on at the neighboring X-10 site, which was renamed the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The Graphite Reactor, built as a demonstration project to show that nuclear material could be extracted for a weapon, became a giant testing site at which researchers could study how to develop and manipulate reactors.

ORNL made a mark in other ways besides reactor development. It became a prime source of radioisotopes, used in weapons research, in medicine including genetic and cancer research, in energy and in radiography.

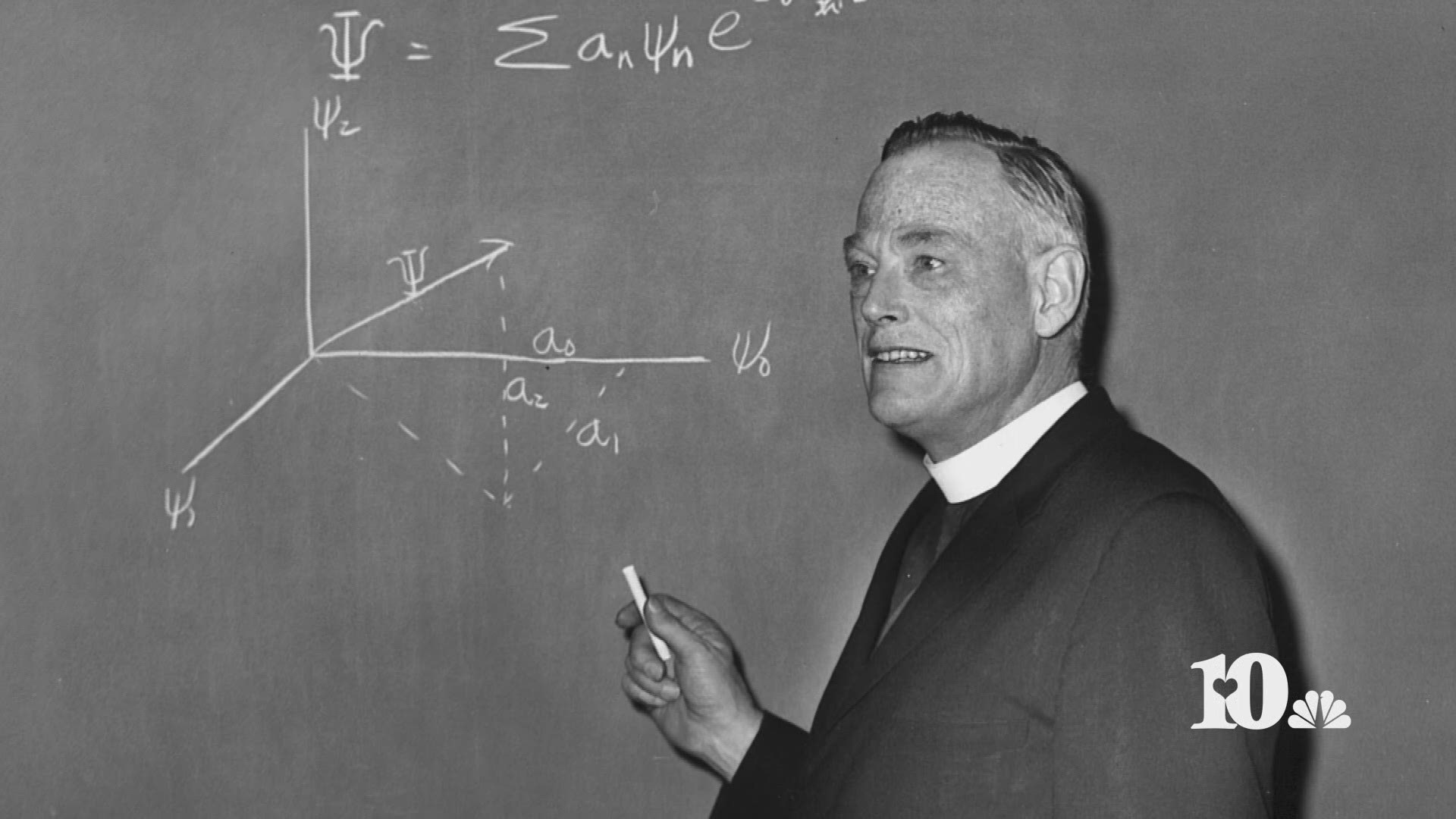

Biophysicist Alvin Weinberg, who came to Oak Ridge in 1945, eventually became the lab's director, serving until 1973.

"If God has a golden book and writes down what it is that Oak Ridge National Laboratory did that had the biggest influence on science," the late Weinberg once wrote, "I would guess that was the production and distribution of radioisotopes."

Dozens of research projects have been launched at ORNL over the years.

It helped in the development of the first nuclear-powered submarine.

Starting in the late 1940s, Bill and Liane Russell oversaw a long-term mouse genetics lab dubbed the "Mouse House" that led to multiple discoveries over the next 60 years relevant to human beings. For example, Liane Russell and others would identify the significance of the Y chromosome in male mice.

In the mid 1960s, ORNL began looking into ways to turn seawater into fresh water for consumption and agriculture.

Scientists helped design a scoop that Apollo 11 astronauts used to collect rocks from the moon. They also studied what the rocks were made of once astronauts returned to Earth.

"The story of Oak Ridge is really the story of American science," said David Keim, ORNL communications director.

The Oak Ridge reservation would not escape controversy after World War II. The very fact that nuclear weapons could pose such a threat to the human race made Y-12 a target for protesters from around the nation.

"Nuclear weapons keep us safe in the same way that a loaded pistol on your dining room table when your kid is alone in the house keeps you safe," said Ralph Hutchison of the Oak Ridge Environmental Peace Alliance, a leading critic and watchdog of the plant.

Some view it as their duty to be vigilant and outspoken about what's happening at Y-12.

"It would be a terrible thing if the Y-12 nuclear weapons plant was manufacturing weapons of mass destruction and there was no voice of peace confronting it on a regular basis," Hutchison said.

Most protests have been peaceful; some were provocative and proved embarrassing to the government.

In July 2012, Sister Megan Rice, Michael Walli and Greg Boertje-Obed cut their way through the grounds at Y-12 and made their way to the Highly Enriched Uranium Materials Facility in the most sensitive area of the plant. They sprayed it with graffiti and threw human blood on it.

It was a security breach of historic proportions.

When guards finally showed up, the trio sang and surrendered peacefully. Each was convicted in federal court and served time in a penitentiary.

Decades of research and production involving volatile materials also have left a legacy of contamination. Many buildings within the reservation are tainted, radioactive and hazardous.Tons of mercury, used in research and production over the years, remains in the ground and groundwater at Y-12, according to the federal Office of Environmental Management.

Multimillion-dollar cleanup projects are ongoing, relying on constant federal funding.

Beacon on the hill

Research into an array of areas continues today at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, drawing an international field of scientists. They're looking at new developments in energy, ways to use carbon fiber in automotive parts, exploring building materials that can self-heal to adjust for heat loss or gain.

"There are about 84 flags that hang from the rafters that represent the countries of origin of our staff, so essentially these are some of the brightest talent globally who have come mostly to pursue an education in the United States and then working here," said director Zacharia.

Advanced computers simulate global weather patterns. The goal is to understand and anticipate through modeling the long-term effects of weather patterns on energy use.

Last summer the lab announced a team was working on a way, using roadside sensors, to create algorithms that could help catch fugitives or travelers who are sought in AMBER alerts. They would create a vehicle "fingerprint" that could help locate a wanted subject.

One of the most high-profile centers for research is the Spallation Neutron Source on the ORNL campus. The $1.4 billion facility became available to scientists in 2007. It produces neutrons that can then be studied by scientists in fields such as materials science, chemistry and biology.

ORNL also has established a reputation as one of the world's prime centers of supercomputing. Giant computers can run simulations and models that can help predict various actions and reactions in science.

The lab has operated a series of ultra-fast computers over the past 15 years or so. The current ace computer is called Summit, and the lab unveiled it in June. It's eight times faster than the lab's previous big brain, known as Titan, according to ORNL.

At peak performance, Summit can handle an estimated 200,000 trillion calculations per second. One area it will help researchers: artificial intelligence.

Zacharia is a champion of supercomputing.

"We are also beginning to start the procurement of the next machine that when we deploy will be the fastest in the world. It’s called Frontier," he said.

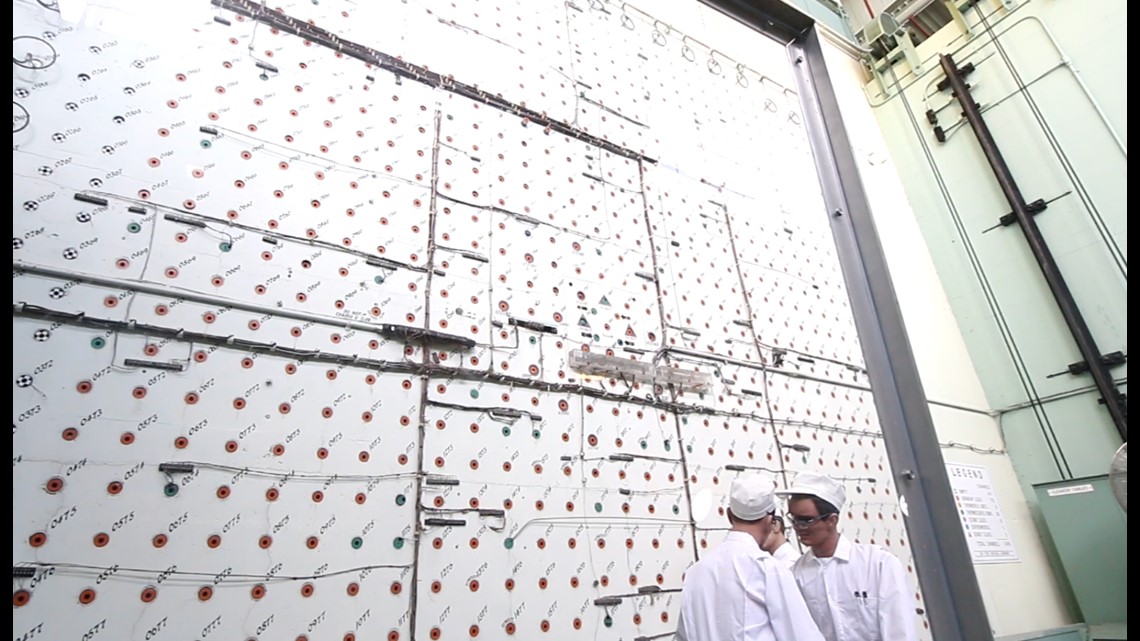

Nearby at Y-12, work is underway on the $6.5 billion Uranium Processing Facility, the new uranium storage complex. It's been under development for years. The UPF, tracking a "build to budget" timeline, is one of the largest projects if not the single largest construction project in the state. It's expected to be ready by 2025.

Its function is dense but key to U.S. security abroad and at home. The UPF will be a uranium storehouse and it will be used to help support America's nuclear weapons stockpile. It'll also "downblend" uranium in U.S. and international weapons to reduce the presence of nuclear weapons on the globe. The UPF also will be a fuel source for the U.S. fleet of nuclear-powered subs and aircraft carriers.

"In itself, it's a historical event here at Y-12," said UPF federal project director Dale Christensen. "In some ways it's replicating what happened during the Manhattan Project."

While Y-12 focuses heavily on nuclear weapons, its personnel also engage in other projects, such as improving machining technology and creating protective equipment that can be used by soldiers in the field, according to Consolidated Nuclear Security LLC, the plant operator.

It's been 75 years -- 76, actually -- since the very first work began to create when became the Oak Ridge reservation. But the facility's roots are still remembered and honored.

After years of study and debate, federal officials in November 2015 formally signed agreements detailing how the Manhattan Project National Historical Park will operate. It consists of Oak Ridge, Hanford, Wash., where uranium was processed and gathered for the World War II bombs, and Los Alamos, where the bombs were assembled and the first nuclear blast was tested.

National park operations and features are evolving. Visitors, however, do have the opportunity to see some of the key historic buildings that helped in the creation of the atomic bomb.

The work at Oak Ridge, meanwhile, continues, spurred on by the decades of advances that have come before.

At Y-12, workers quietly go about the business of guarding the nation's nuclear legacy.

"When you're going down the grocery store aisle or sitting in church, you’re liable to be sitting next to somebody who is performing this essential national security work every day," Tindal said. "We silently do that. We’re happy to not have a whole lot of recognition."

At ORNL, research will continue into areas we've not even thought about yet.

"For the next 75 years, my stewardship, my vision for this laboratory is to position us to be the beacon on the hill for the scientific stuff but also for the nation," said Zacharia. "Because troubles will come, and we want this lab to be ready. We want this lab to be a change agent."