OAK RIDGE, Tenn. — When the United States dropped the first of two atomic bombs on Japan, the secret city of Oak Ridge was lauded for its role in fueling the "super-bomb" that effectively ended World War II.

In the 75 years since Hiroshima was leveled by enriched uranium, Oak Ridge became a target for peace activists.

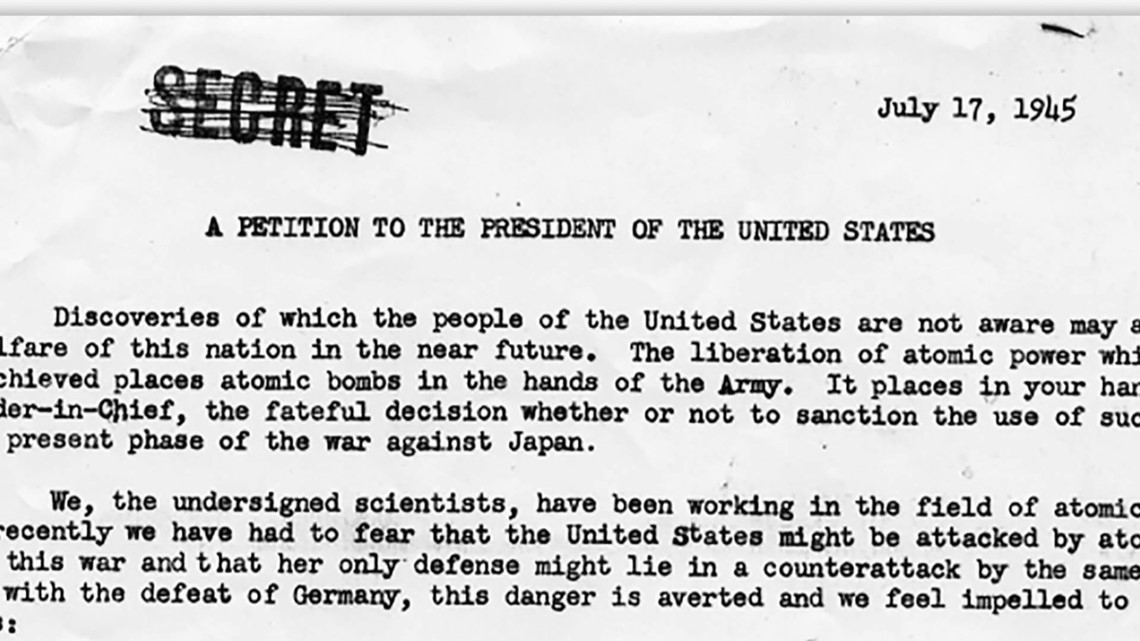

Protests to the use of atomic weapons began before the first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Scientists who helped develop the technology petitioned the president to only use the weapon as a last resort, citing the nation's moral responsibilities. There were requests to demonstrate the weapon's awesome power to Japanese leaders before unleashing it on a city.

Oak Ridge continued to fuel the nation's nuclear arsenal throughout the Cold War. The city's role in an international arms race put a bullseye on Oak Ridge for activists.

In 1983, a dozen anti-war groups gathered in Oak Ridge for a silent vigil. They held hands and formed a large circle. They held banners reading, "No More Hiroshimas" and "Stop the Arms Race, Save the Human Race."

Each year, the gatherings grew on the anniversaries of the atomic attacks.

Religious leaders, including many Catholic nuns, made their point by crossing the line between protesters and trespassers engaging in civil disobedience. Activists gathered and chanted at roadblocks in 2001, with many crossing the barriers knowing they would be arrested.

While managers of Oak Ridge facilities touted their tight security of the nation's nuclear arsenal, in 2012 peace activists caused them an unprecedented level of embarrassment.

An 82-year-old nun, a man in his mid-60s, and a man in his late 50s cut through several fences and reached the outside of the Y-12 Highly Enriched Uranium Materials Facility (HEUMF). The trio spray-painted messages of peace on walls and roads. They also splashed bottles of donated human blood on the outside of the HEUMF.

"All we want is the truth to come out about the criminality of nuclear weapons and their fallout on this planet for 70 years," said Sister Megan Rice outside federal court in Knoxville.

All three activists served time in federal prison for the break-in. They also forced a shutdown at Y-12 to reexamine security.

"We should be very grateful that they're beginning to think about it [security]," said Rice in 2012.

Along with anti-war protests, Oak Ridge's legacy also includes calls for friendship with the cities it helped to destroy.

In the mid-1990s, the city installed a large friendship bell with the dates the atomic attacks.

"It symbolizes Oak Ridge's birthday. Born of war, which is true. Living in peace. And growing through science," the late Herman Postma, former director of ORNL, said at the bell's dedication.

The bell also brought controversy from people who did not want it to be confused as an apology. Creators of the bell insisted it would only resonate as a symbol of goodwill, friendship, and international peace.

The friendship bell and the decades of protests both ensure messages of peace are part of the legacy of a secret city that fueled a weapon that made the world tremble.