SEVIER COUNTY, Tenn. — A federal survey into the Chimney Tops 2 fire that devastated Gatlinburg reveals most people were unprepared and largely unaware of danger that was growing up to and during the night of November 28, 2016.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology published a report in late July on its survey that studied 323 people who lived in Gatlinburg and were present when the fire was happening.

Its findings were eye-opening: The majority had been largely unaware of wildfire risks after days and weeks of smoke in the air, had never been through an evacuation before, and only a small percentage said they were warned or received information the fire was present through official sources or an evacuation notice.

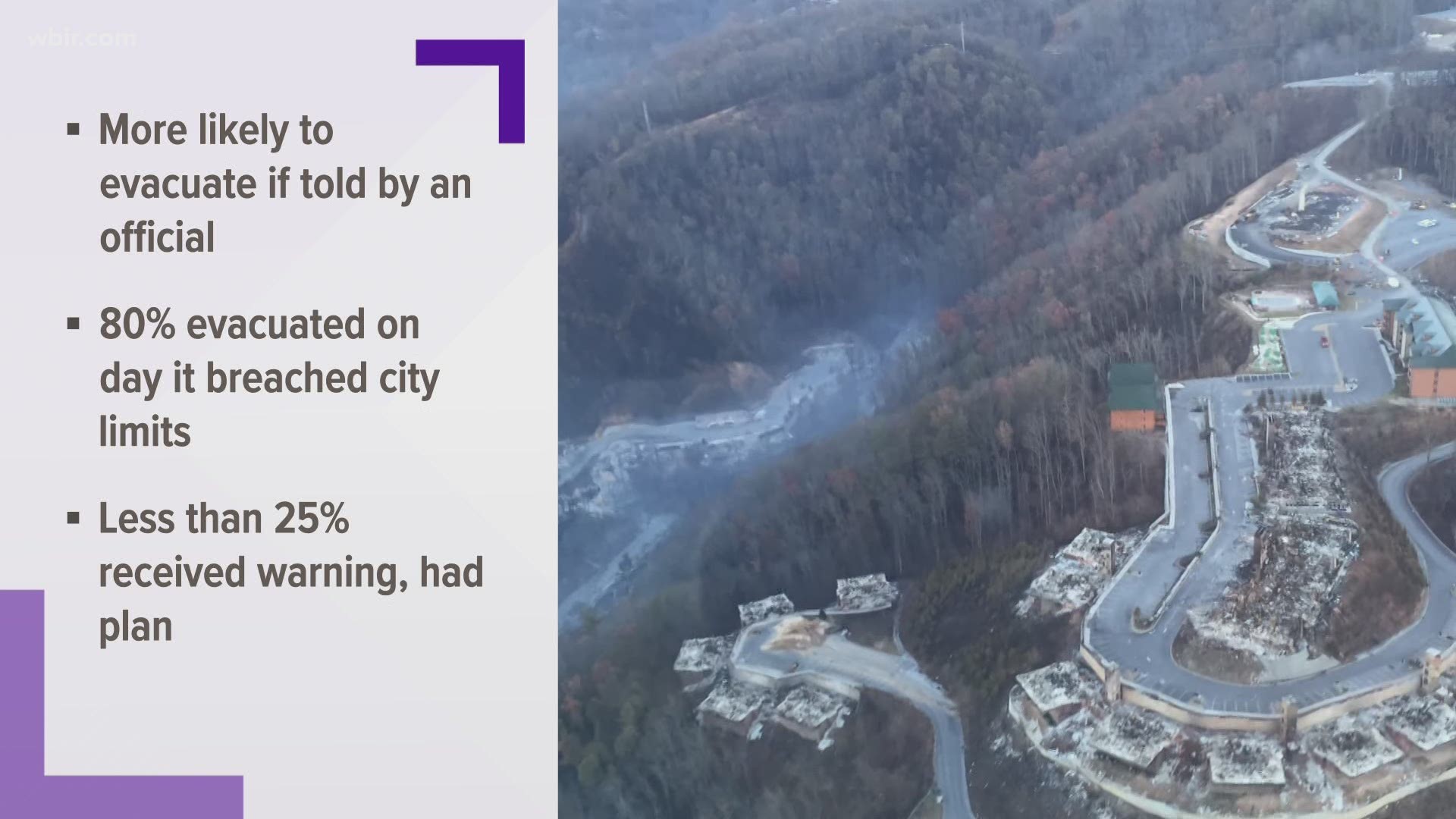

Participants said they were more likely to evacuate once they were told by officials.

"It seemed that people expected that if a large wildfire requiring evacuation was going to happen, they would be told. Instead many had to find out on their own," Emily Walpole with the NIST said.

Rep. Phil Roe (R-Johnson City) said this study will help in the future to understand how to prevent future tragedies nationally before impending emergencies grow dire.

"The Gatlinburg wildfires were a senseless tragedy, and my heart still breaks seeing images of the fire’s destruction," he said. "Particularly now as wildfires are raging across our nation, the lessons we can learn from studying previous tragedies can help save lives now. I think we all need to reflect upon what was learned from East Tennesseans who lost loved ones, friends, homes, and businesses."

The fall of 2016 was one of the hottest and driest on record -- creating a drought with severe wildfire potential. As dead leaves and brush piled up on the dry ground in early November, fire burn bans were issued across East Tennessee, including in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Gatlinburg issued its open burn ban on November 3.

Dozens of rural wildfires across the state of Tennessee had broken out around the same time -- creating a steady haze and smell of smoke that lingered for weeks across East Tennessee.

The Chimney Tops fire had first been detected on November 23 in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, filling the air around Gatlinburg with thicker smoke. Because people living in the area had grown acquainted to the sight and smell of smoke over the weeks and days before the disaster, the study concluded it lowered most people's guard even as the fire spread past the park boundary and into Gatlinburg.

"The long-term presence of smoke actually lowered residents’ sense of danger," Roe said. "Fast-moving wildfires present a unique threat, so it’s critical we learn from this tragedy to better protect people in the future.”

When asked if they knew wildfires would be a problem in their community before the Chimney Tops 2 fire, more than 25% of the 323 participants said "not at all." Another 57.5% had only lightly considered it possible. Just 10% believed wildfires in the area were a "very good possibility."

More than 55% said they took no preparation actions ahead of the wildfire. Most of the ones who did either moved or removed mulch and woodpiles on the ground around their homes.

When asked how many official or mandatory evacuation notices they received before evacuating Gatlinburg, 83% said they received zero warning or did not remember getting one. 11% said they received 1 warning at some point, and the remaining 6% received 2 or more.

There were 73 participants who said they received some sort of official or unofficial warning about a fire before it had spread beyond the Great Smoky Mountains National Park boundary. The majority of those, 62.5%, received that warning the day of the fire. 29% remember being warned in some way about the wildfire when it was still contained in the park.

Of the 73 who remember receiving at least one warning, nearly 60% said it came from an unofficial source, such as a neighbor, friend or co-worker. 33% said they got it from local media, and 18% said it came from local police or fire officials.

When describing their evacuation decision-making process, 280 of the 323 made the decision to do so. Of the 280, 81.4% made the decision once they saw fire cues. Women were three times more likely to evacuate than men.

People who decided to leave due to fire cues said feeling heat, seeing flames, embers or a red glow in the distance were the deciding factor.

Nearly all observed smoke. Of the 34 who discussed their awareness of the fire that day in greater detail, most said they were not concerned by smoke and did not believe they were at risk to personally being affected by the fire -- saying they had been exposed to smoke for days and weeks before evacuating.

Of those who did not evacuate, 42% said it was because they were not ordered to do so. 30% said they stayed to protect their property, and 25% said they didn't because they received no warning.

You can read the full study below: