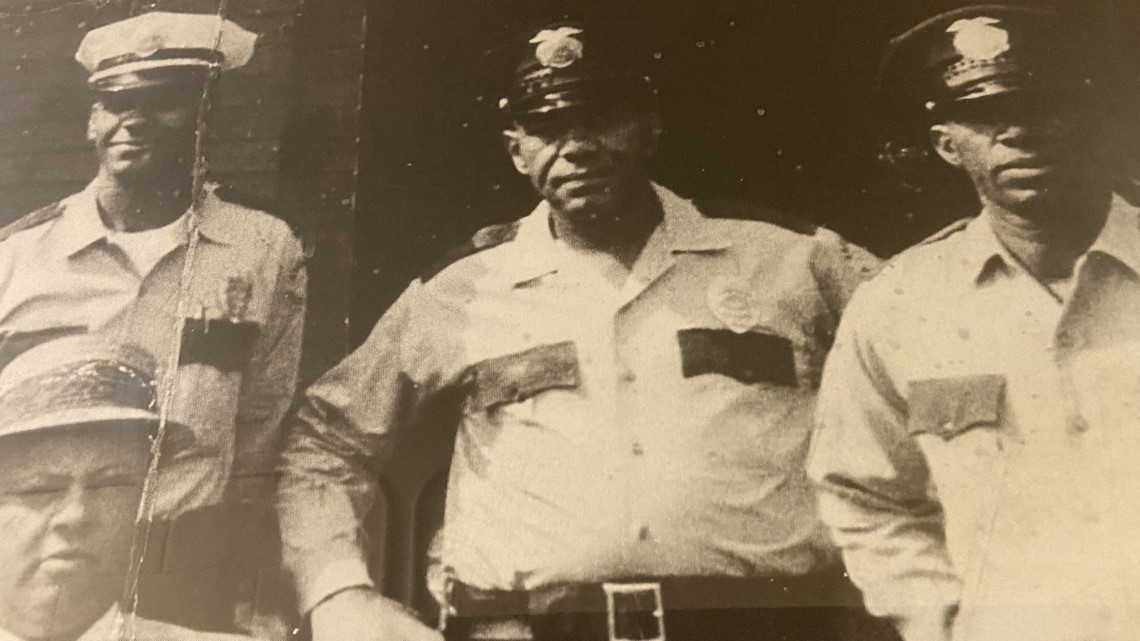

KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — Nestled between the pages of the Knoxville Police Department's history are the first African American officers to ever serve the city.

"In the 1870's we were one of the only cities in the southeast to have black police officers black firemen and black city councilmen," Detective Jason Booker said.

Booker is a homicide investigator, but also serves as the department's museum curator.

When it comes to who was the first, he said history records two names in particular.

"Moses Smith and AB Parker, it's between Moses and A.B. Parker," he said.

Part of his job is to share that history with new recruits.

"We can't grow or get any better if we don't know where we came from," he said.

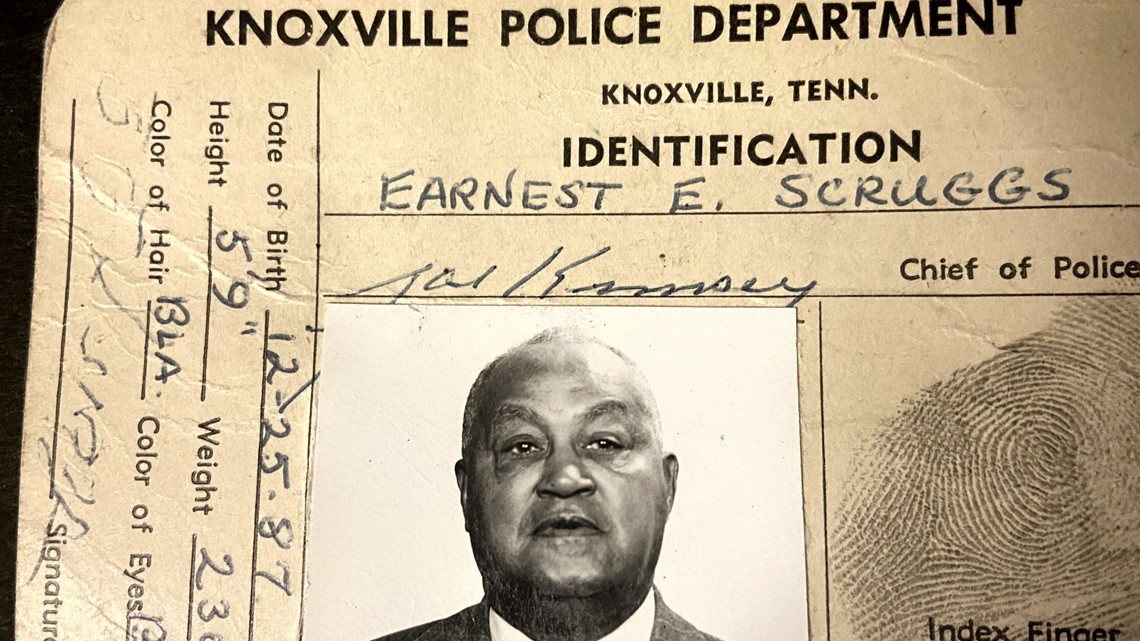

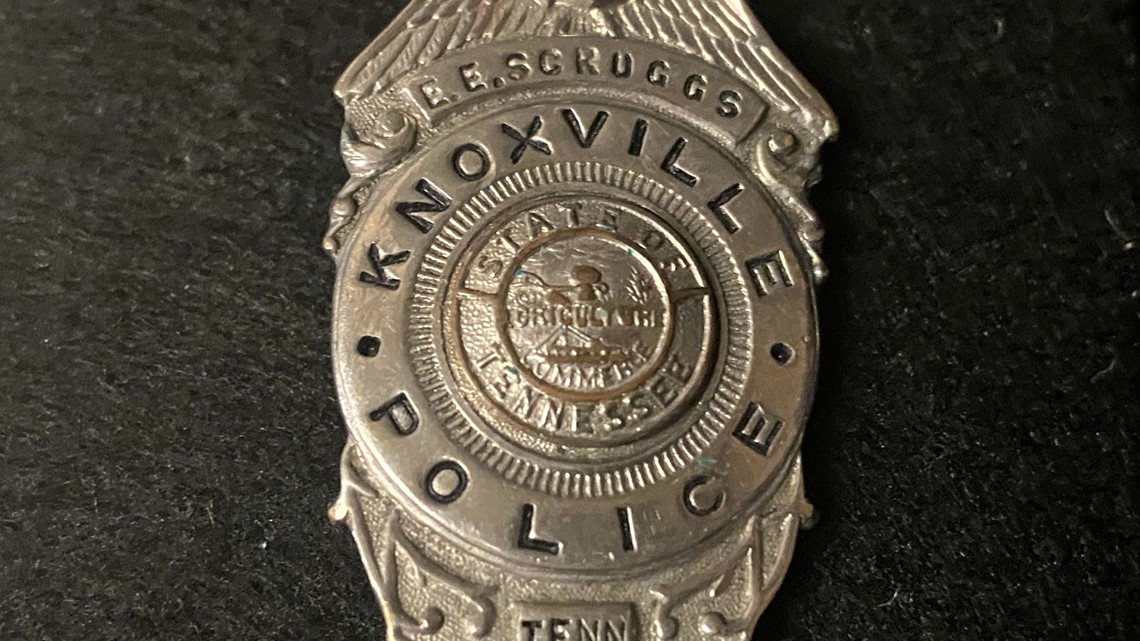

Stories about people like Earnest Scruggs who was the first African-American detective.

"Scruggs came on in 1914 and so he was with us for five years before the race riot in 1919 so he was here at a time when race relations really exploded," Booker said.

The 1919 Race Riots would go down in history as the Red Summer.

That same year race relations across the country came to a boiling point.

Here in Knoxville, it all started with when a man by the name of Maurice Mays was charged with killing a white woman and sentenced to death.

To this day historians hold that there was no evidence tying him to the crime and several groups have asked Tennessee's governors to pardon Mays over the years to no avail.

The city wouldn't bring in its first African-American female officer until 1955.

In newspaper clippings from the time she is referred to as Mrs. William Henderson, the mother of four and the wife of a city fireman.

But there is another story Booker likes to share.

"I touch on officer James Mason, I spend a ton of time on Mason," he said.

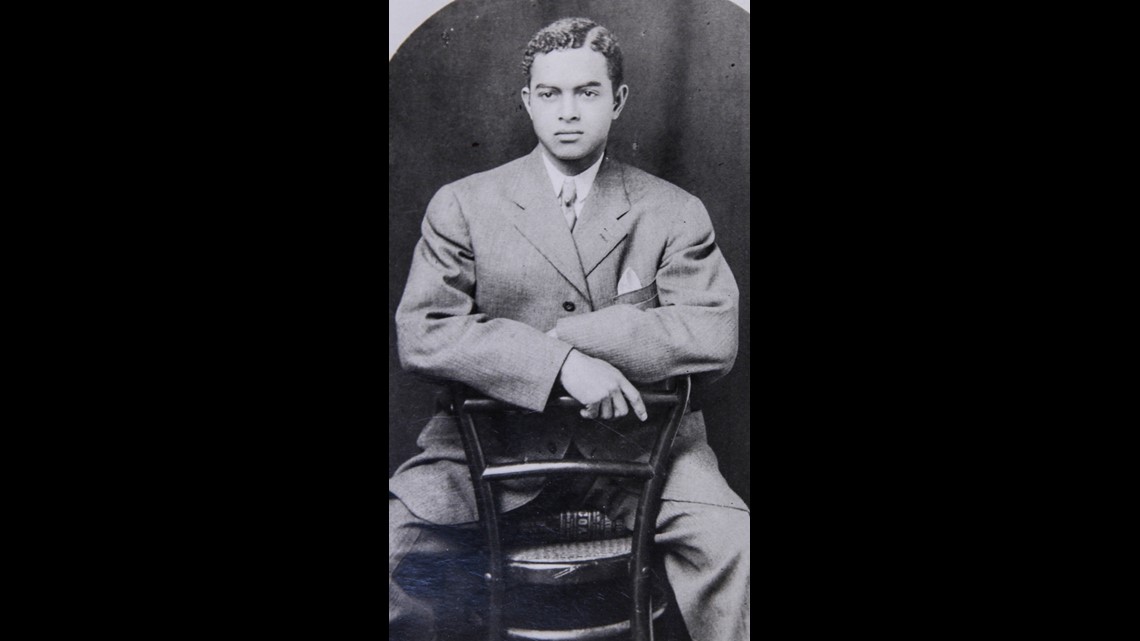

Mason was born sometime in the 1840's but history didn't record his exact birth or death.

"Officer Mason was actually born a slave and he worked for us for 18 years," Booker said.

Before he became an officer he bought his own freedom and was working to buy his wife's when slavery was abolished.

Newspaper clippings say mason went on to open a school for deaf children. At the time, schools would not admit African-American children to deaf schools or any school with white children for that matter.

With that in mind, Mason created his own.He later retired in 1902.

"This is a man who didn't owe anybody anything. If there was a man who was entitled to have a chip on their shoulder, it's a man who was born into slavery. But he didn't," Booker said.

According to Booker, Mason was the kind of man he didn't want any of his officers to forget.

"I tell them there are people in our history that you want to emulate, and he's one of those guys," he said.

While their experiences in a time period that didn't allow for much inclusivity or equality was hard, Booker adds it is a story we have to share that hardship nonetheless.

"It really builds on our history," he said. "Even if we don't talk about it, it happened so not talking about it doesn't do anybody any good."