Centuries after his death, Isaac Dockery remains a guiding light for descendants

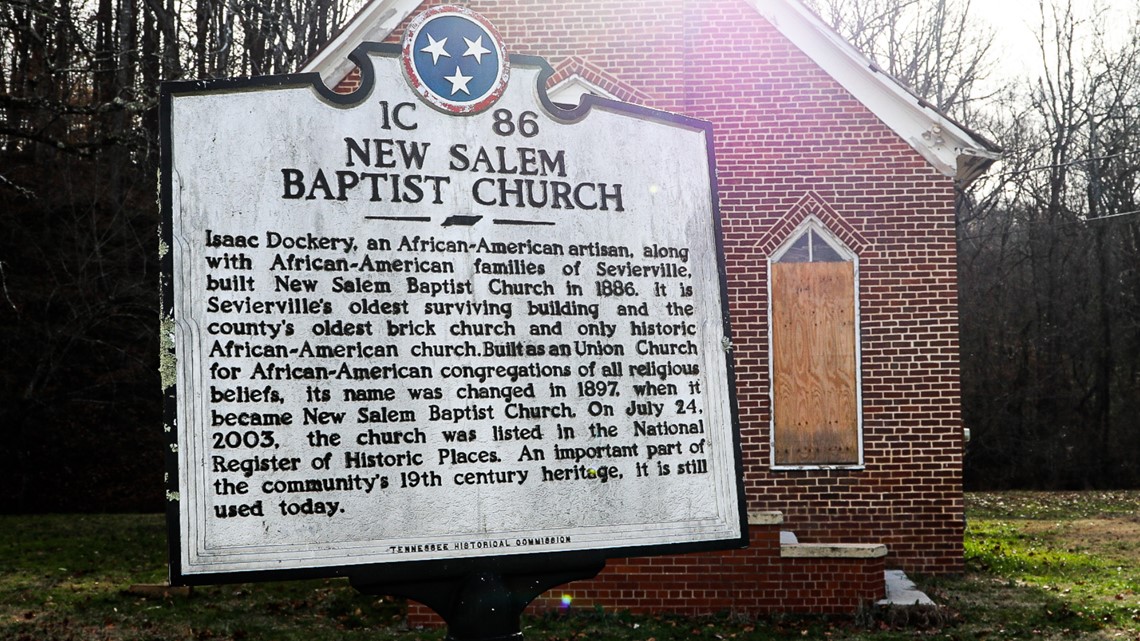

In 1886, Isaac Dockery laid the last brick into what is now the oldest standing brick structure in Sevier County. For his family, it is a clue into their past.

This is the first part of Stolen Stories - a series about two families in East Tennessee who have retraced their history back to the most recent slave in their lineage.

Far back against the banks of an impatient creek in Sevierville is a place that would seem holy - hollowed grounds where spirits of past and present come to congregate - even without the place of worship standing solemn at the treeline.

Though gospel hymns and sermons stopped ringing out from New Salem Baptist Church long ago, it remains much unchanged since it was first built in the late 1800s.

The doors are bolted, planks of wood cover the cathedral style windows, and cement steps softened over the years by moss and time lead the way to a locked iron gate.

A Lasting Legacy Subtitle

Shedenna Dockery comes here often – and is used to seeing the looks of surprise on passersby face when their eyes land on these red clay bricks that have withstood the whims of history.

“People look over here sometimes and they’re like, 'whoa,’” Shedenna Dockery said. “You almost feel like you’ve stepped back in time.”

DISCOVER MORE: Stolen Stories | Reclaiming the lives of Tennessee slaves

To Shedenna and her family though, this seemingly humble church isn’t just some picturesque glimpse into the past.

For the Dockery family, this church is their past.

Because although they lived centuries apart from each other, Shedenna knows well the man whose prodigious skill and hard work built something sacred along these banks.

His name was Isaac Dockery, and he was her great-great-grandfather.

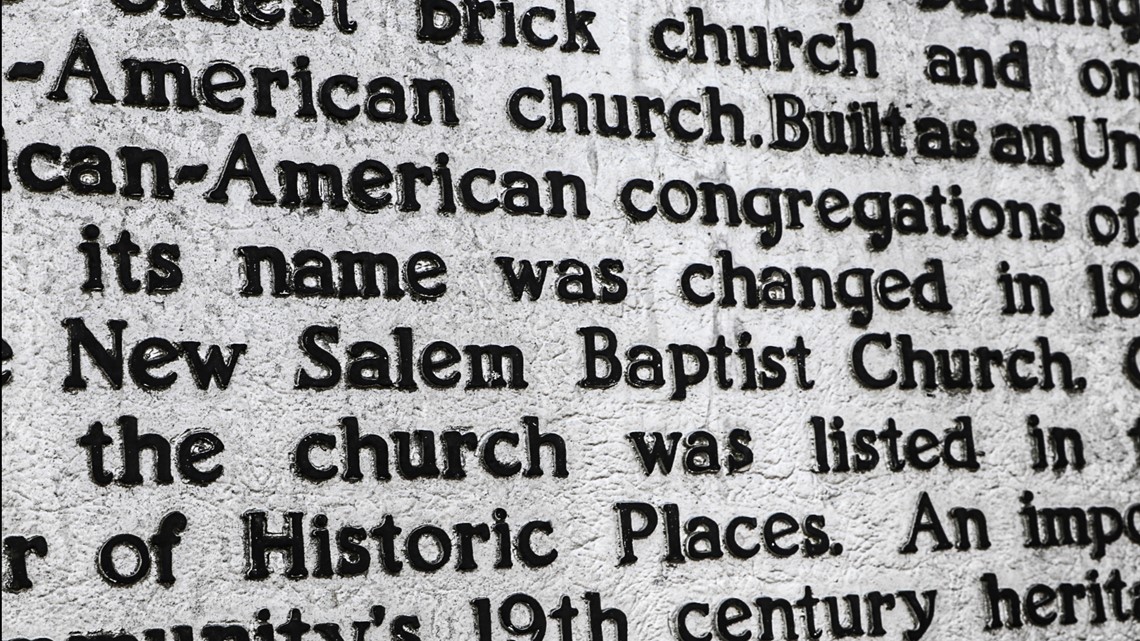

It was in 1886 that Isaac Dockery and his colleague, Lewis Buckner, would put the finishing touches on a church that would eventually become the New Salem Baptist Church.

While today it holds the distinction of being the oldest brick structure in Sevier County, it held another sort of significance during Dockery’s lifetime.

He built this house of worship as a place for all people, with ideals of unity that stood in contrast to the harsh attitudes of his time.

"It is nice to know your family history. It is so nice to know where you come from. It is really nice to know the people responsible for getting you here," Ronald Brabson said.

Shedenna Dockery and Ronald Brabson are cousins, and share not only a great-great-grandfather in Isaac Dockery, but a guiding post. As children, the elders in their family made sure they knew who Isaac and Charlotte Dockery were.

"Me and Shedenna both we were close to our grandparents," Brabson said. "They would tell me things and stories and stuff they would answer questions but not go into detail. When I started in '94 looking into the family, all of a sudden I missed my grandparents. Because I'm like, I know I've been told about this but now I really want to hear it!"

As adults, they vowed to learn as much as possible about the people who carved out this place from the ground up.

“I think it’s fair to say Sevier County would look very different without Isaac Dockery,” Shedenna said.

Piecing together stories from their and their own strong oral history, they began to trace the life of this prolific ancestor.

The Brickmaker's Mark Subtitle here

The last time records show Dockery working for anyone other than himself was in the home of a prominent merchant clerk named McKinley Thomas. He honed his skillsets, specialized his craft, and fell in love with a woman who worked as a slave in the Thomas household.

"That's where he met Charlotte. And we do know there are living descendants of 13 of those children," Shedenna said.

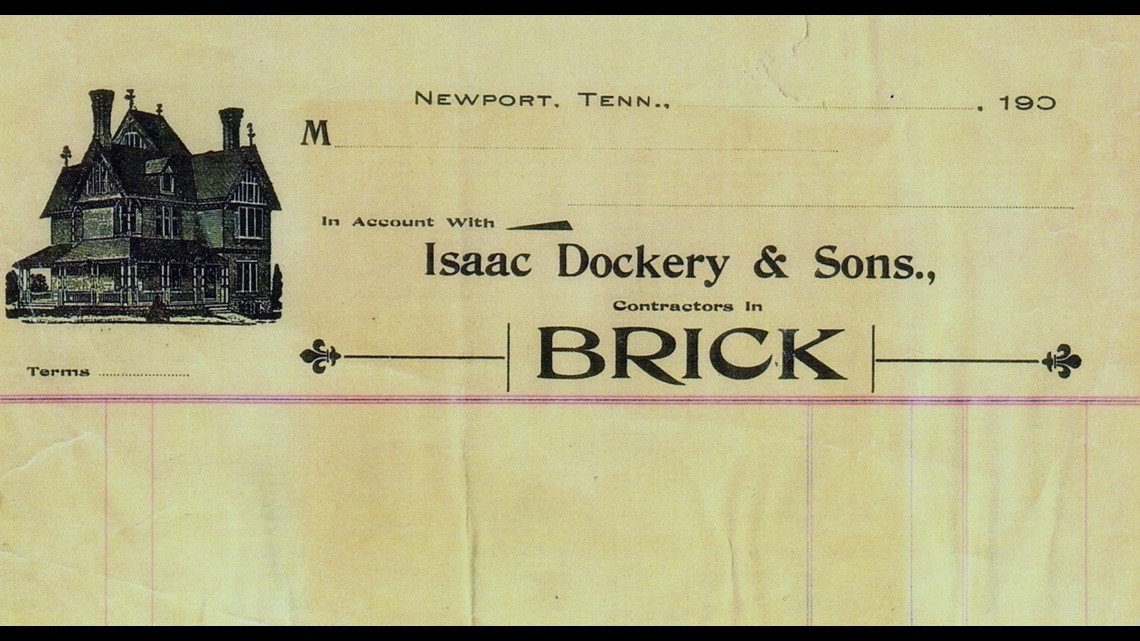

Isaac Dockery was not a slave. He was a free man, and a prominent one in Sevier County. He owned property in three counties in East Tennessee, ran his own construction business, and was a major player in community affairs.

Through years of research and storytelling, Shedenna, Ronald, and other members of the Dockery family have not only come to understand the basics of his life - where Isaac lived, what he did for a living, how many children he had - but understand more extraordinary details.

In an era where people were building their own kilns for bricks on their front yards, then knocking them down, the way their great-great grandfather operated his business was totally unique.

“He decided to make a kiln big enough that you could make brick for other people,” Brabson said. "He was the very first one to do that in the area.”

Before long, people across Sevierville were wanting both the quality and craftsmanship of Isaac Dockery’s bricks for their own homes.

In his lifetime Dockery wasn't just making buildings; he was forging connections. His talent motivated white people to cross stringent racial lines of the day.

"What was so unusual was that he sold brick to white construction companies and that didn’t happen. You didn’t have clients that were both black and white," Brabson said.

While New Salem Baptist Church holds a sentimental significance for Dockery’s descendants and a historical one for the greater Sevierville community, it is hardly the only structure in town with his fingerprints on it.

Long before a bronze statue of Dolly graced the lawn of the Sevier County courthouse, it was Isaac Dockery’s bricks holding it up.

He would often inscribe the bricks with his initials, ID.

“A lot of structures in East Tennessee were made with Dockery bricks," Shedenna said.

It was a prodigious skill he did not keep to himself.

Rather, Dockery passed it along to his sons and daughters, who also helped build the church.

An old photo from when the church was built shows not Isaac Dockery alone - but working collaboratively with his family.

Emboldened with a trade he had perfected, the Dockery descendants would follow in Isaac's footsteps, building Sevier County and beyond from the ground up. Several generations of builders, Paris Witt McMahan, George and Stewart Burden, Bill Coleman, and Fred McMahan can directly trace lineage back to Dockery.

"I sometimes wonder if Isaac and Charlotte will realize how many of their descendants are schools teachers...nurses. We have a large number of nurses, and we have a large number of school teachers as well as masons," Brabson said.

Skills are far from the only thing Dockery was known for - he was remembered for the strength of his character.

Ronald and Shedenna recall a situation when, as a Union soldier during the Civil War, Isaac Dockery’s bravery saved a man’s life.

“Near the end of the Civil War, this area kept switching backwards and forth depending on where you were. The white family, the Thomases….the ones that owned my great-great-grandmother, they were Union.”

Fearing for their lives, the Union supporting Thomases fled. As Confederate soldiers descended on the town, they tasked Isaac Dockery with looking after their entire property and merchant store.

It wasn't long before Confederate soldiers were swarming Sevierville, looking for Isaac.

“The Confederates came looking for him they asked Isaac where McKinley Thomas was," Shedenna said.

The Confederate soldiers tied a rope around his neck and drug him through the streets of a downtown he helped build.

Isaac never gave in.

“From what I understand he bore those scars for the rest of his life – where he was actually drug through the city,” Shedenna said.

Her great-great grandfather's bravery shaped the future of Sevierville.

“Because what would happen if he gave up Mckinley Thomas? What would have happened? They could have burned the city and the courthouse," Shedenna Dockery said. “I think it would have been a totally different city if Issac would have not been here….Isaac and Charlotte."

A Guiding Light Subtitle here

When he Isaac took his last breath in 1910, he did not do so in obscurity. In an age when his own wife had worked as a slave and Confederate soldiers drug him through the streets by his neck, the local paper honored his life.

His great-great grandson would read and cherish those words centuries later.

"There was an obituary in one of the Sevierville papers," Brabson said. "It talks about...a trusted loyal colored man died today. And he was known as Uncle Ike. And it tells he was the most honorable man and he was trusted by both black and white."

It's that spirit of endurance Ronald sees reflected in his own family today.

"You can see a little bit of him in different relatives. You can. They say he could be a real firecracker and that he wasn’t a big man and you can see that spirit in some of the cousins," Brabson said.

There are many of these cousins, who gather once a year to celebrate the lives of Charlotte and Isaac.

The Dockerys left behind dozens of buildings upon his death, and - crucially - legions of family who would scatter across the states.

The Dockery family kept branching, moving, and merging. Some of them did not stray far from East Tennessee. And for the ones who continued to call the mountains home, New Salem Baptist Church provided a starting point for others to dig into their family history.

Among those are Julia and Michele Daniels. They are two women from Oliver Springs whose family would go on to create a trade and homestead from the very land where an ancestor was enslaved.

All because one woman survived.

Her name was Adaline.

►In Part II of Stolen Stories- Meet Adaline Crozier, a woman who worked as a slave in Oliver Springs and whose children would go on to change the East Tennessee we know today.

►Make it easy to keep up-to-date: Download the WBIR 10News app now and sign up for our Take 10 Lunchtime Newsletter.

Have a news tip? Email 10Listens@wbir.com, or visit our Facebook page or Twitter feed.