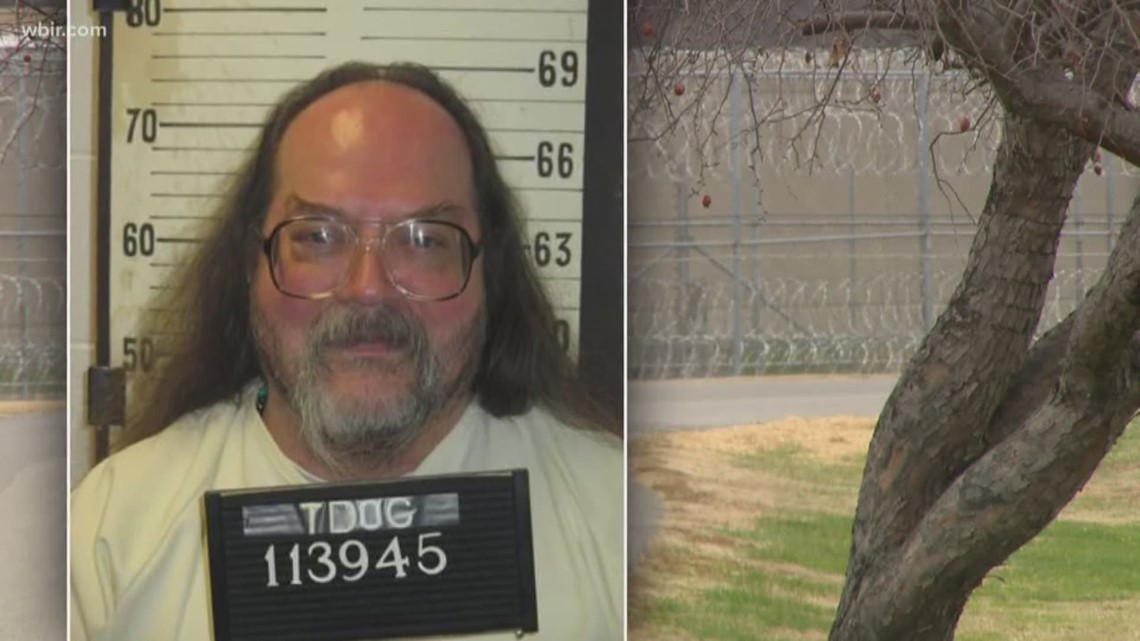

NASHVILLE, Tenn. — Tennessee death row inmate Nicholas Sutton went to his death Thursday night thanking his family and praising God.

The Lord can fix anything, even a broken man, he said.

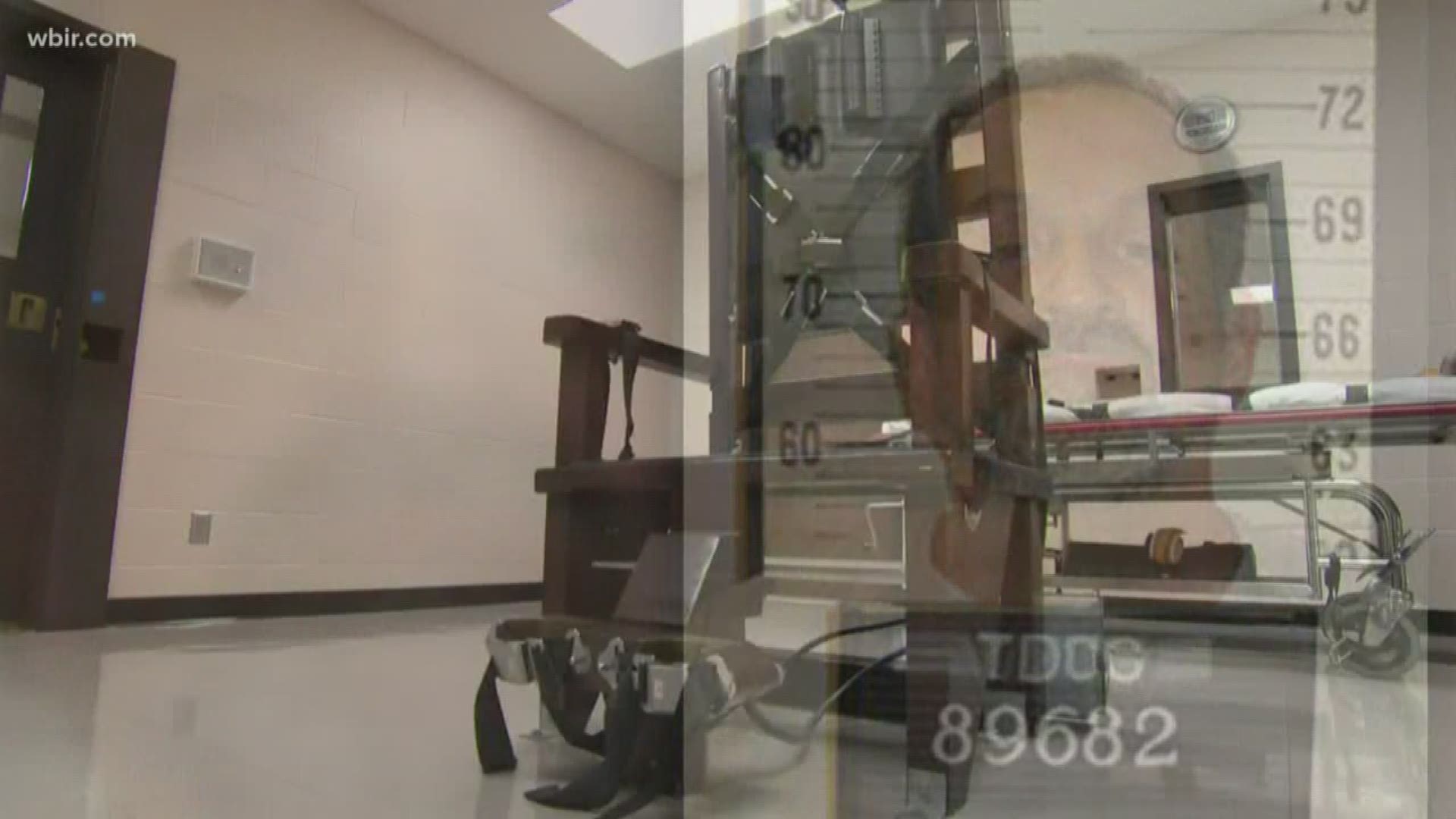

"I'm just grateful to be a servant of God and I'm looking forward to being in his presence," the 58-year-old inmate declared as he sat in the state Department of Correction's electric chair.

Moments later, as I stared from the witness chamber at his cloaked head, someone inside the Riverbend Maximum Security Institution hit his belted body with two jolts of electricity and he was dead.

Five death row inmates including Sutton have elected to die by electrocution since the state resumed carrying out death sentences in August 2018 after a nine-year lapse.

Two others have been put to death by lethal injection -- a series of three intravenous doses.

In August 2018 I served as an official witness on behalf of WBIR as the state killed Billy Ray Irick, 59, by injection for the rape and murder of a little Knoxville girl named Paula Dyer in 1983.

At 7:18 p.m. Central time, 8:18 p.m. Knoxville time, I saw Sutton’s body jerk backwards into the electric chair as the first current hit him. His pink fingers tightened together on the chair arms. Then came a second shot of electricity.

The media witnesses -- a handful of us -- watched through the glass for any signs of life for another six minutes. Then prison officials lowered the blinds.

Two minutes later -- at 7:26 pm Central -- he was declared officially dead.

Of course it’s foreign to watch the government deliberately take someone’s life from them.

RELATED: Tennessee death row inmate Nicholas Sutton chooses last meal after Gov. Lee declines to intervene

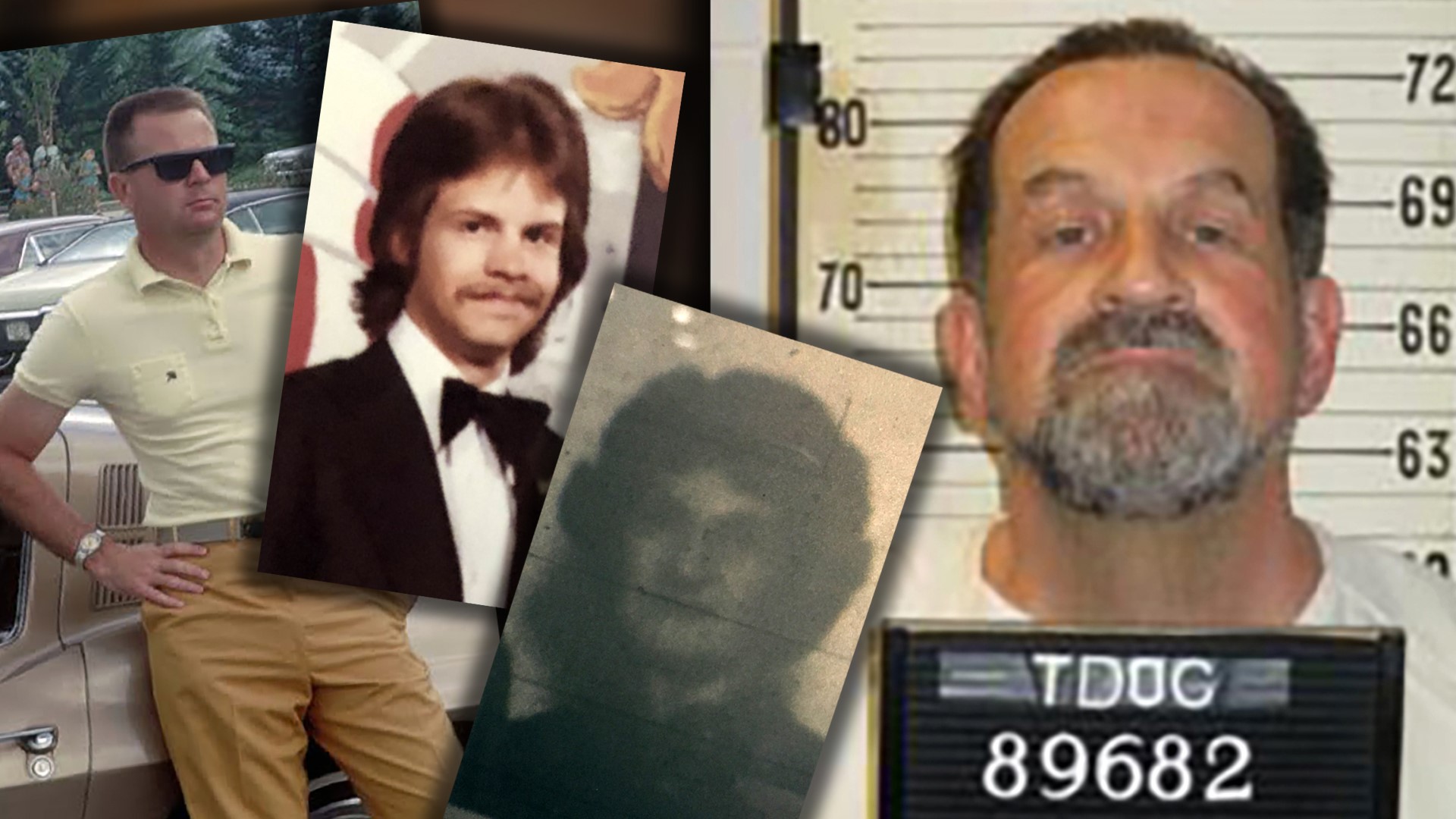

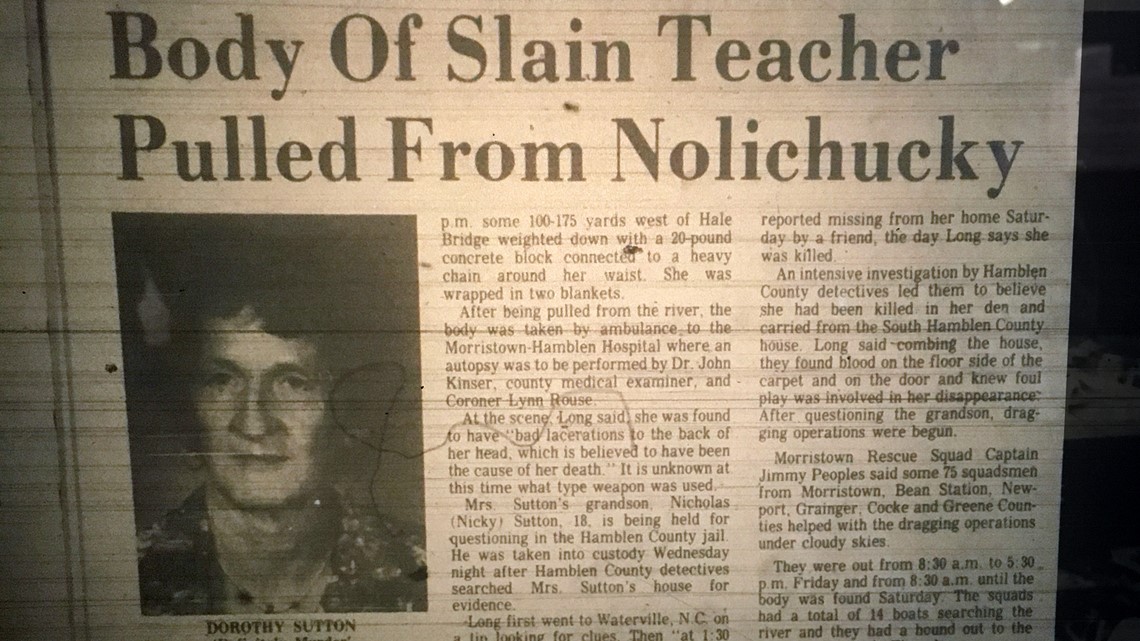

In this case, Sutton was executed for the murder of Morgan County Correctional Complex inmate Carl Estep in 1985. But by then the Morristown man already had murdered his grandmother, Dorothy Sutton, his friend, John Large, and his former employer, Charlie Almon.

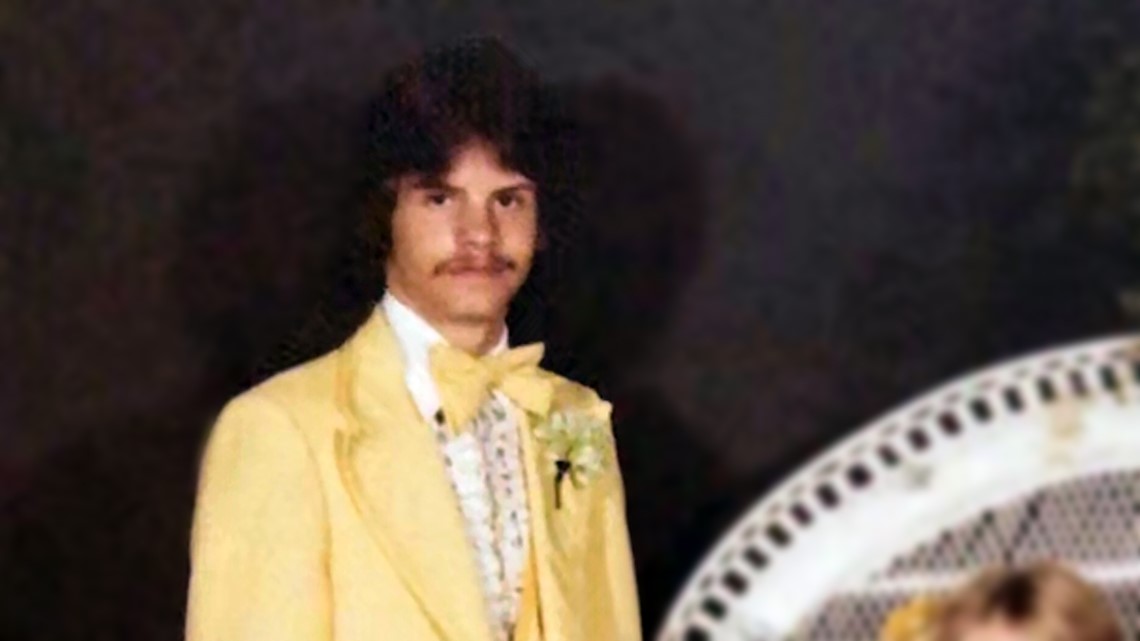

He killed them all within months of each other in 1979. He was 18.

His grandmother, 58, was still alive when he dumped her bound body into the Nolichucky River in December 1979, an autopsy showed. He drove a stake through the 19-year-old Large's mouth as he killed him on family land in North Carolina, apparently in August 1979.

And he bound up the 46-year-old Almon's body after killing him in North Carolina and dumping his victim in a Cocke County quarry in 1979.

After the execution, as we stood in a tent in the prison parking lot, TDOC spokesman Dorinda Carter read the media a statement from Amy Large Cook, the sister of John Large.

"John was denied the opportunity to live a full life with a family of his own," the statement reads. "My children were denied meeting a wonderful man who would have spoiled them rotten and loved them with all his heart. He suffered a terrible and horrific death.

"And for that, I will never forgive Mr. Sutton."

Sutton said nothing Thursday night about his victims as he delivered his final words.

He thanked his wife, his friends who had tried to stop the execution and he talked at length about the power of Jesus to heal the wounded.

"I hope I do a much better job in the next life than I did in this one," he said in a prepared statement read after his execution by attorney Stephen Ferrell.

'FIXING TO KILL HIM'

I can’t imagine making a choice between lethal injection and electrocution.

With injection the person appears to go unconscious, snoring loudly, maybe occasionally jerking involuntarily. It's a process that seems to take many minutes.

Defense attorneys argue the sedative used to put an inmate out -- midazolam -- doesn’t work. It doesn’t fully knock the inmate out, they say, and the person experiences drowning sensations as the drugs begin to work.

I can’t say I saw any sign from Irick back in 2018 that he was suffering.

Is the electric chair any better? It is certainly quicker.

While Irick’s chest went up and down for several minutes on a gurney as the drugs slowly took effect and as his skin turned purple, Nick Sutton never appeared to move after being shocked twice.

It’s what happens in the moments before prison officials turn on the electricity that gives some the chills.

They shave your head until you're completely bald. They pour a saline solution over your head and legs to ensure better electrical conductivity. They lock your head in a helmet.

You have to blink your eyes to ward off the sting of the salt water. Then, they snap a hood across your face.

When they’re done strapping you in, a prison official kneels down on the floor, grabs an electrical cable and plugs it into an outlet at the chair's base.

There's a faint hum and then comes the jolt.

About 30 minutes before I was led along with the other witnesses into the prison to await Sutton’s execution, I called a man named George Webb.

The 60-year-old Newport resident said he was a childhood friend of Sutton’s. They ran around together as teens, he said.

They did drugs together -- and that’s what he blames for Sutton’s crimes more than 40 years ago.

“I hate that they’re fixing to kill him,” said Webb, who signed a petition seeking his clemency and spoke to Sutton's lawyers on his behalf.

Sutton wasn’t all bad, he said. In his last days, Webb said, Sutton would telephone him daily.

He talked about God and spirituality, Webb said.

“I’m here to tell you that God is real,” Webb told me, recalling one of his last conversations with Sutton.

If Sutton is right, he is now in the presence of the Lord.

So are, presumably, Dorothy Sutton, John Large and Charlie Almon.

Because of what he did to them, they got there first.