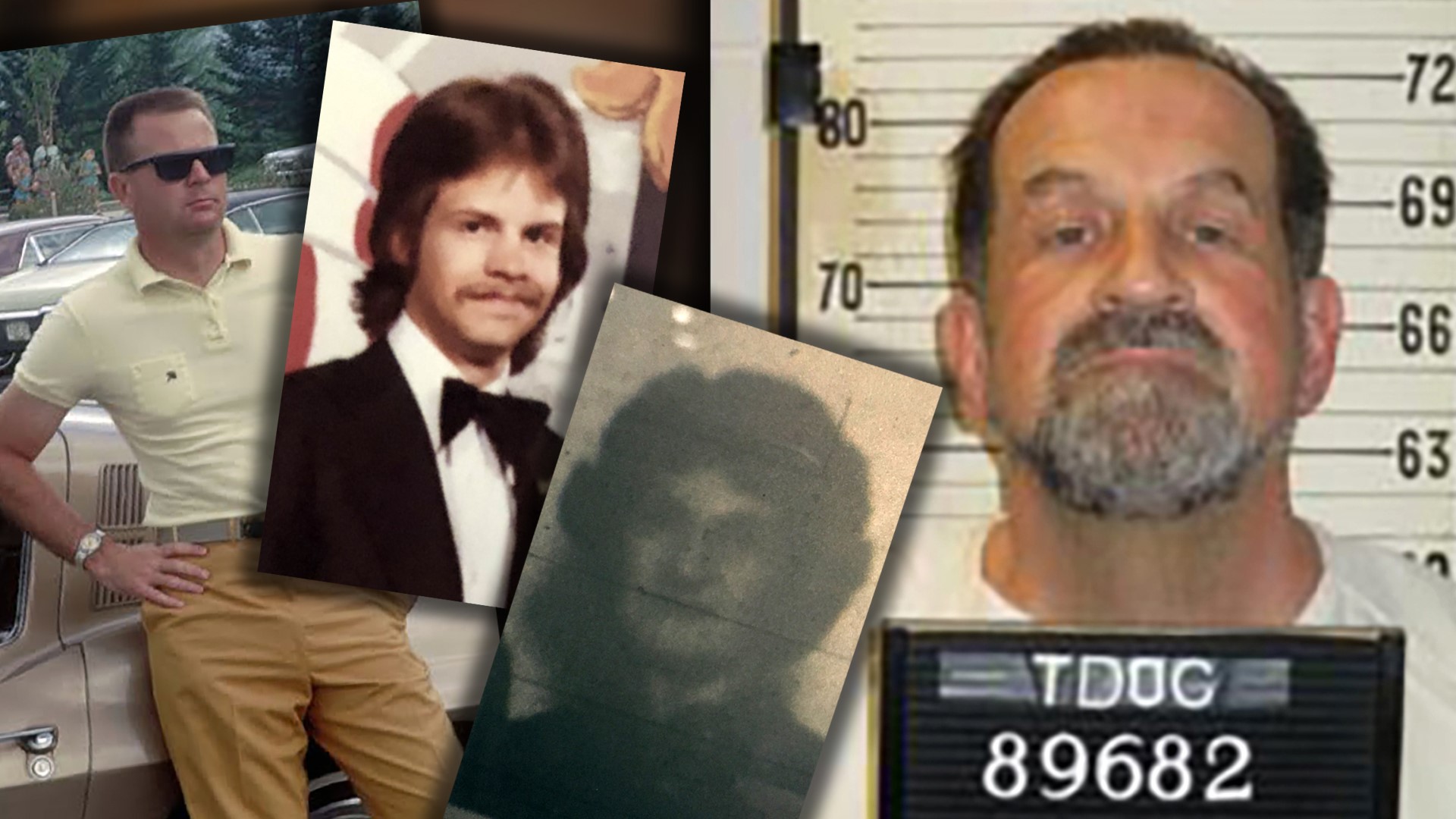

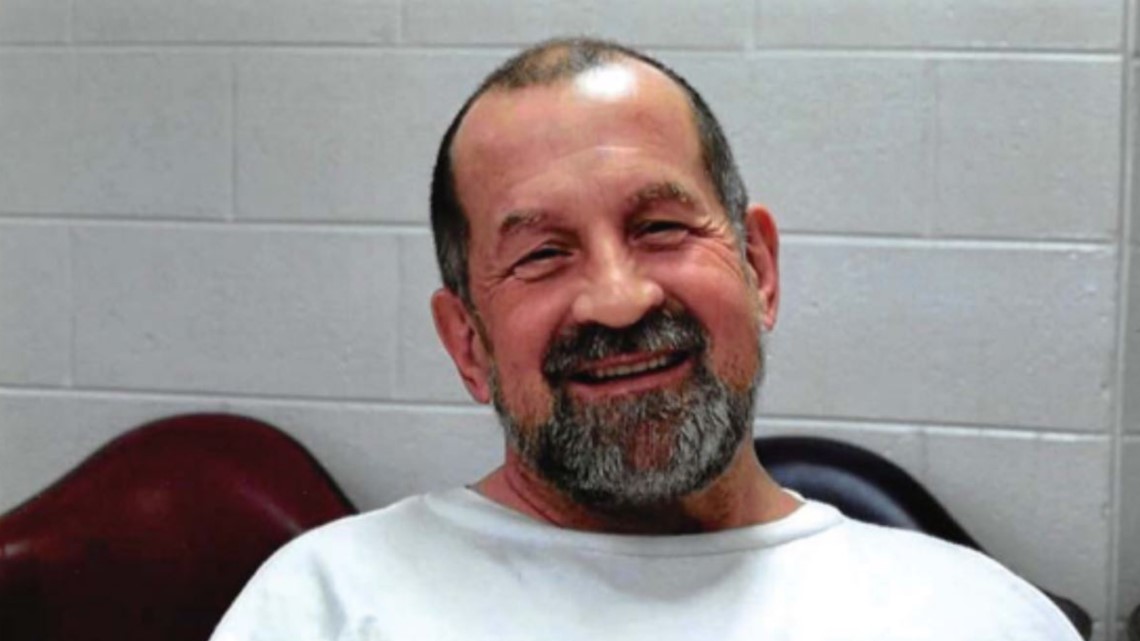

KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — Nicholas Todd Sutton is scheduled to die in the electric chair Thursday night in Nashville. The 58-year-old has been on death row since 1986 for murdering a fellow inmate in 1985. It's been more than 40 years since three murders put Sutton behind bars as a Morristown teenager.

The public's memory of Sutton's crimes has faded. So has the memory of his victims. But the memories remain fresh for those who knew and loved the people caught in Sutton's spree of violence.

TEACHER, BROTHER, UNCLE

In 1979, Nicky Sutton was an 18-year-old high school dropout with an expensive drug habit. His father committed suicide in 1976. Nicky lived with his grandmother. Dorothy Sutton was a respected retired elementary school teacher who gave her grandson a home, support, love, and money.

"Some of my friends and assistant principal had Mrs. Sutton. They all loved Mrs. Sutton. She was a very giving and loving person," said Amy Cook, a teaching assistant at Russellville Elementary School.

Cook knows the respect the community had for Dorothy Sutton. She also knew Nicky Sutton.

"We called him Nicky, but I call him Nick or Nicholas now. Nicky sounds too personal. He was over at my house a lot when he and my brother were in high school. My brother was John Large. We played and fought like all brothers and sisters do, but I loved him and he had a big heart. I sometimes wonder if his big heart didn't get him in trouble, because he would befriend anyone," said Cook.

Cook said she remembered Sutton as someone who was very respectful to her parents and endeared himself to her with frozen treats.

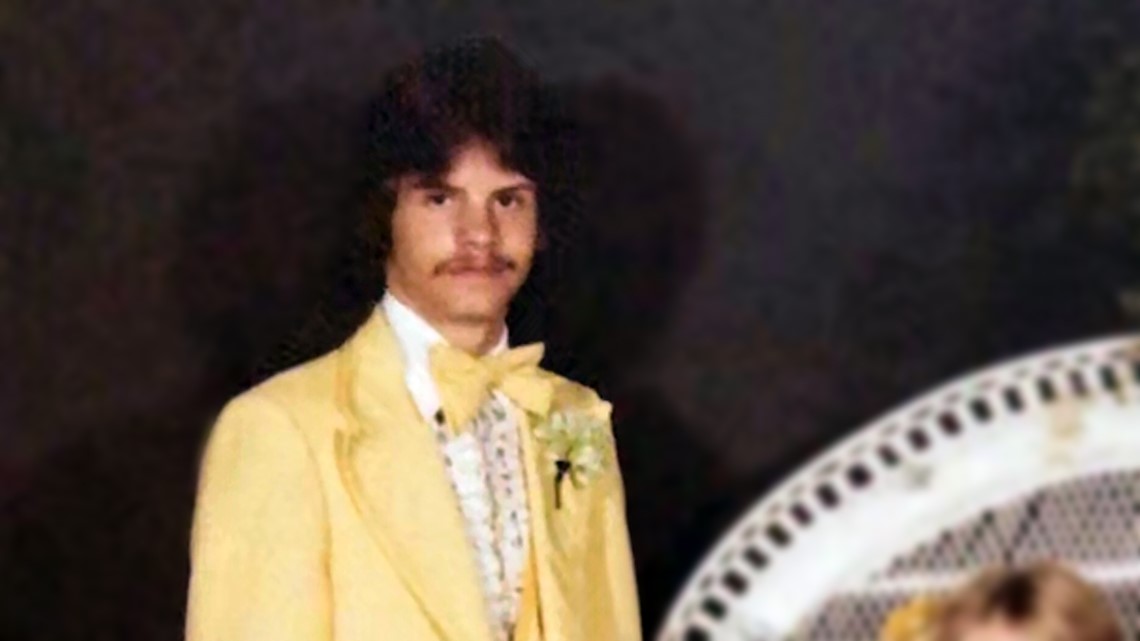

"He drove an ice cream truck. He would bring me ice cream when he came over to see John. I was just starting sixth grade when John disappeared," said Cook. "He was 19, had just been married less than a month, and Nick supposedly went by John's apartment in Knoxville and picked him up. There was a drug deal that was going down and John went with him, probably to make a few bucks. Nick came back and told my sister-in-law the deal went bad and John left with all the money."

Around the same time 19-year-old John Large disappeared, so did a charismatic 46-year-old engineer from Knoxville who owned an up-and-down business as a land reclamation contractor.

"My uncle was Charles P. Almon, III. Uncle Charlie, he just loved history and the beauty of the mountains. He just loved this area. I was the fourth generation with the name Charles," said Reverend Charles Maynard.

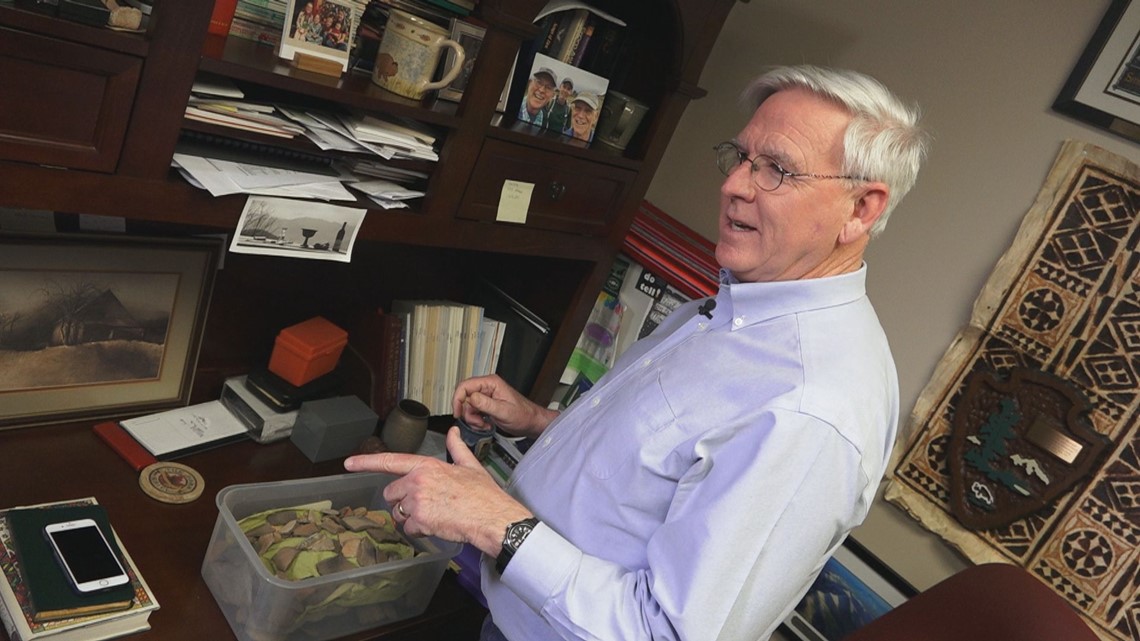

Maynard is well-known in East Tennessee as a longtime Methodist reverend, author of history books, and avid outdoorsman who was the first president of the non-profit Friends of the Smokies.

"My love for the outdoors partially comes from him. He loved the outdoors and he loved prehistory. We would go after it rained in tilled fields and find arrowheads and broken shards of prehistoric pottery from Native Americans. He really wanted me to know as a kid that this area's human history goes back thousands of years, not just the last few hundred years since Europeans settled," said Maynard.

Maynard describes himself as a "geek or nerd" and said his uncle was the opposite. Charlie Almon was a star athlete with musical talent and the mind of an engineer.

"Even as a kid, I knew he was really cool. Look at the pictures of him and just his pose is so cool," laughed Maynard.

Maynard said his uncle met Nicky Sutton during his days as a land reclamation contractor.

"You need people who will go in and plant thousands of pine trees. And so, he had hired Nick for those kinds of jobs," said Maynard.

In September 1979, Almon's habitual Sunday phone calls to his parents in Signal Mountain stopped.

"My grandmother told me they were really worried. We haven't heard from uncle Charlie in a few weeks. That was a long time to not hear from him at all," said Maynard.

Almon's Jaguar sports car was found near Newport with some valuables still inside. But there was no sign of Almon anywhere.

The family of Charles Almon had no clue where he could be. John Large's family knew he was last seen with Nicky Sutton. Large's father repeatedly asked Dorothy Sutton to see if Nicky had insight on John's whereabouts.

Just before Christmas 1979, Dorothy Sutton was also missing.

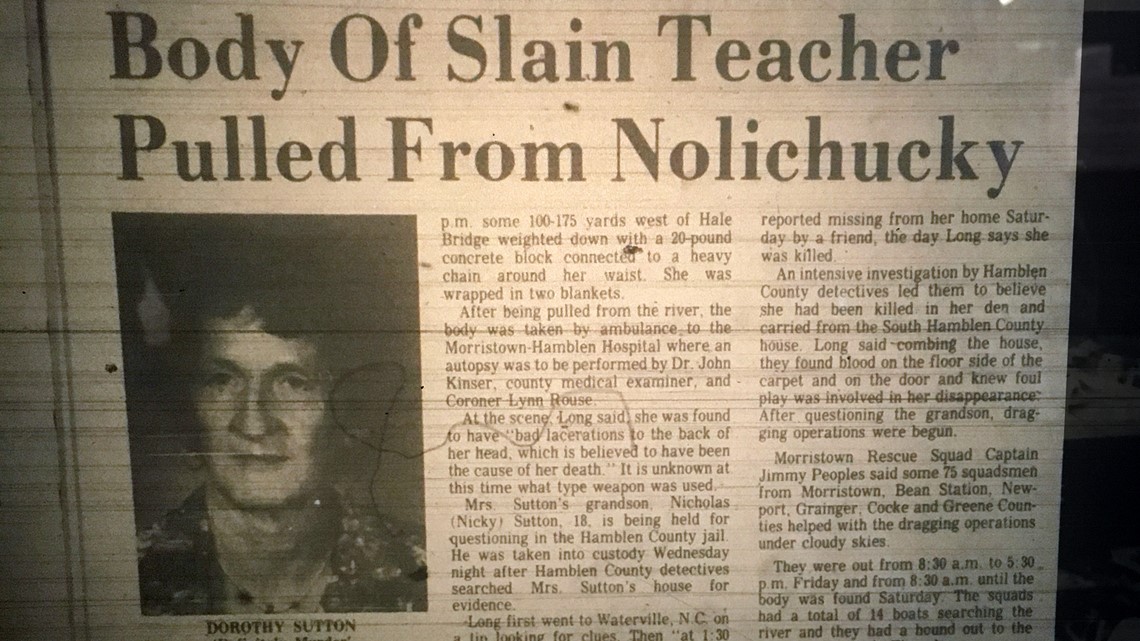

GRANDMOTHER'S GRIM DEATH

Nicky Sutton told relatives his grandmother left the house with an unknown man on December 22. The story didn't make sense. Dorothy Sutton's relatives suspected wrongdoing by Nicky Sutton. But it was Nicky who reported his grandmother missing on Christmas Day.

Detectives in Morristown saw signs of foul play at the home and took Nicky Sutton into custody. Within a few days, they extracted enough information to start dragging the Nolichucky River for her remains.

Nicky Sutton bashed his grandmother in the back of the head, wrapped her in a couple of blankets, and chained her body to a 20-pound concrete block. Coroners said Dorothy Sutton was not quite dead when Sutton dumped her body from the Hale Bridge, and the official cause of death was drowning.

Nicky Sutton's murder trial in April included a confession that he killed someone. Not his grandmother. Sutton claimed he killed Charles Almon and labeled him a drug dealer from Knoxville. Sutton cooked up a far-fetched story that he came home to find Almon had killed Dorothy Sutton. Nicky claimed he was then attacked by Almon and killed him in self-defense before dumping both bodies in the river.

The jury didn't buy Sutton's story and sentenced him to life in prison.

PRISON CONFESSIONS, WILD GOOSE CHASE

When Nicky Sutton was convicted of his grandmother's murder, he began to confess to other murders. He told investigators he killed 19-year-old John Large and led them to a shallow grave on some family property in Mt. Sterling, North Carolina.

Then Sutton began bragging of two other murders that never happened. The names he gave investigators were fake. But Sutton managed to spend several days away from a prison cell while he feigned the search for graves.

"If you look at the old pictures, he was not in 'cuffs. He was liking that freedom of being outside and I think he loved the attention," said Cook.

In May 1980, investigators had recovered the bodies of two of Sutton's victims. There was still no sign of Charles Almon. Investigators came across his remains accidentally.

"They were diving in a rock quarry in Newport looking for evidence in another case and found my uncle," said Maynard.

Charles Almon's body was wrapped and chained to a concrete block, just like Dorothy Sutton. The autopsy showed Almon was dead several months before Dorothy Sutton, further proving Nicky Sutton was lying about any involvement by Almon in her death.

"I think that's what made me as mad as anything were the claims he made about my uncle. At that point, my uncle was already dead and there was no way for him to offer any defense. But it was mostly a feeling of overwhelming grief that we lost someone I loved so much," said Maynard.

Maynard was a young Methodist reverend when his uncle's body was recovered. Maynard officiated the funeral service for Charlie Almon.

"I remember getting choked up during the funeral service and my brother came up and put his arm around my back. It was just a terrible time full of grief for me and my family. My grandparents lost their only son," said Maynard.

FATAL SENTENCE FOR FOURTH MURDER

In January 1985, Nicky Sutton was serving three life sentences for three murders. Sutton and another man stabbed fellow inmate Carl Estep 38 times over drugs. Estep was a convicted child rapist from Knoxville. His murder was the fourth strike that convinced a jury to send Sutton to death row.

While had continued a life of violence behind bars, Amy Cook said her own parents continued to blame themselves for the death of Dorothy Sutton.

"Until the day he died, my dad felt guilt for Mrs. Sutton's death. My dad felt like if he hadn't called Mrs. Sutton and asking will you check with Nicky again and see if he's heard from John, maybe he wouldn't have killed her," said Cook.

Only Nicky Sutton knows his motivations to kill his grandmother, John Large, and Charles Almon. Whatever the reason, Cook is ready for the state to close a painful and prolonged chapter of her life by executing Sutton.

"I feel like he's wasted enough of the taxpayers' money, sitting there for 40 years. I want closure," said Cook.

Cook said she feels like her brother's story ended when he was killed. But Charles Maynard said his uncle's story will conclude with Sutton's death. His faith led Maynard to ask the governor to spare Sutton's life.

"My uncle Charlie was killed in a senseless act of violence. I don't want his story to end with another senseless act of violence," said Maynard. "To take a life anywhere cheapens life everywhere. Nick Sutton's taking my uncle's life and others' lives cheapened all of life to the point even his life is cheapened. Taking one more life is not going to equal any balance for me."

Maynard said not all of his family agrees with his request for clemency. But a great-aunt who was a Methodist deaconess made the point Sutton should be spared decades ago.

"She went to Sutton's trial in Waynesville. She didn't call him by his name. She would only call Sutton 'that man.' And later when Sutton was on death row, she said to me that we cannot let 'that man' be executed. I felt that way already, but it was significant to hear she felt the same way," said Maynard.

Former prison guards and relatives of other murder victims joined the call for Governor Bill Lee to grant clemency to Sutton. Lee announced Wednesday he will not intervene.

The relatives of Sutton's victims have differing opinions on capital punishment. But they are united in the desire for people to remember how their loved ones lived rather than how they were murdered.

"John Large was a fun, caring, loving, hard-working young man," said Cook.

"My uncle, he was a cool guy who loved his family and really loved this area," said Maynard.