More than 100 years after it ended, East Tennessee still wants to forget people suffered under slavery here

In retracing their family history, descendants of enslaved people like Charlotte Dockery or Adaline Staples Crozier often have to expose the brutal truth of slavery.

This is the third part of Stolen Stories - a series about two families in East Tennessee who have retraced their history back to the most recent slave in their lineage.

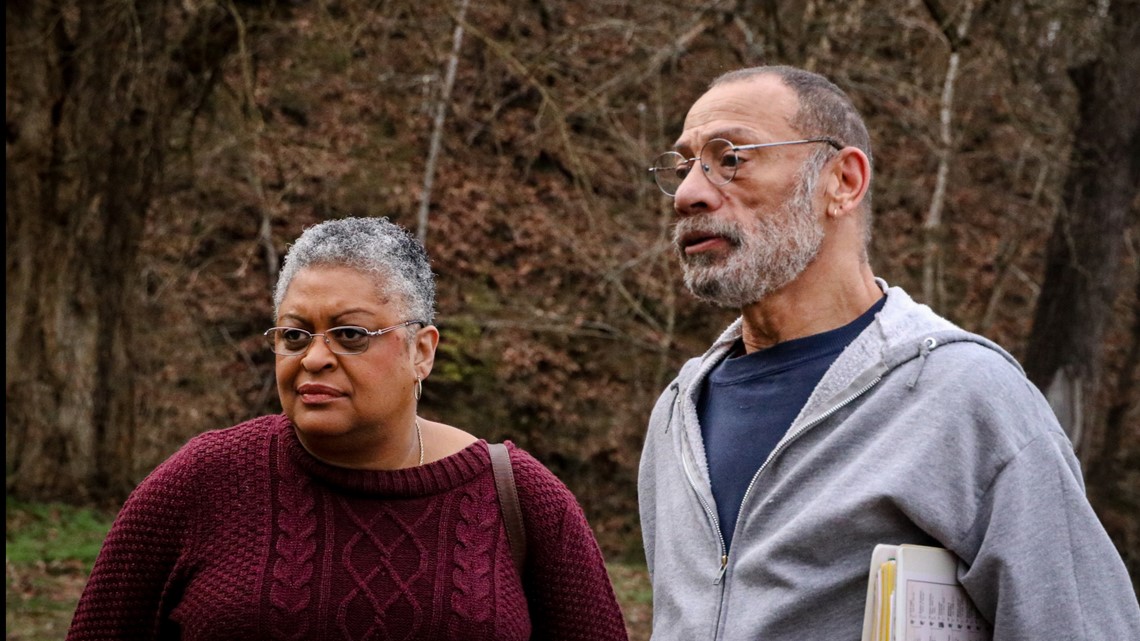

The hours Ronald Brabson spends pouring over archives, sleuthing through records and analyzing data in an effort to piece together missing links in his family tree have not been in vain.

“There was a lot of family members that said well if you find somebody back to 1870 that's as good as you’re gonna get. But I have found one of my relatives was born in 1800. And then, of course on the Dockery side, we can trace them back to the 1700s,” he said.

A Constant Search Subtitle here

Over the years, Brabson has tracked down Dockery descendants in all fifty states except New Mexico and the Dakotas.

There is the author in Indiana who received an immediate and enthusiastic invite to the family reunion upon discovery.

There are the two sisters in California who kept their maiden name when they got married, certain the Dockery name would die out forever.

They were shocked when Brabson told them there were many Dockerys. They were just halfway across the country.

“She was like, wow, we thought we were the only Dockerys! We’ve had that happen a couple of times,” Brabson recalled. “And I told her, ‘If you come to East Tennessee you can meet three to forty of your closest relatives!’”

Like many Americans, Brabson’s passion for researching his family history was aided by the internet. Websites like 23andMe, Ancestry.com, and HeritageQuest Online allow people to track and record their family lineage with ease.

However, when Brabson speaks with other people interested in studying their family history, he often feels a heartbreaking disconnect instead of camaraderie in a similar goal.

“I often have mixed emotions. Sometimes I’m like, no you don’t understand. You have records. You have documentation. I had to scratch. I had to dig. I spent a lot of hours," Brabson said.

What Shedenna Dockery, Ronald Brabson, Michele Daniel and millions of other people descended from slaves in the United States are tasked with is more important than tracing back single surnames or analyzing what percentages of the world their blood contains.

They are trying to reunite families ripped apart by the brutality of slavery.

“If you’re African-American, most of the time, you don’t trace a single surname. You try to put together the family,” Brabson said.

Within that context, the fact that Brabson has been able to track down relatives in so many parts of the country isn't just an example of his prolific research skills.

It is a horrifying reminder of slavery’s power to rip families apart and scatter them from one another.

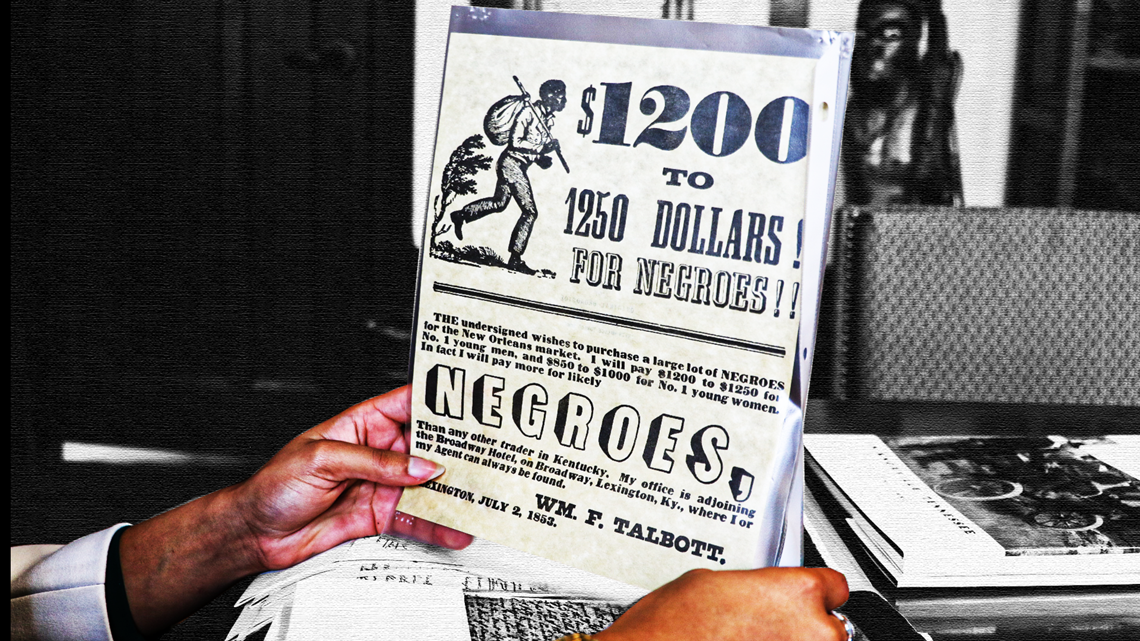

Filling in the blanks often means descendants of people who survived this systemic brutality often have to go deep into the dark recesses of one of history’s cruelest chapters.

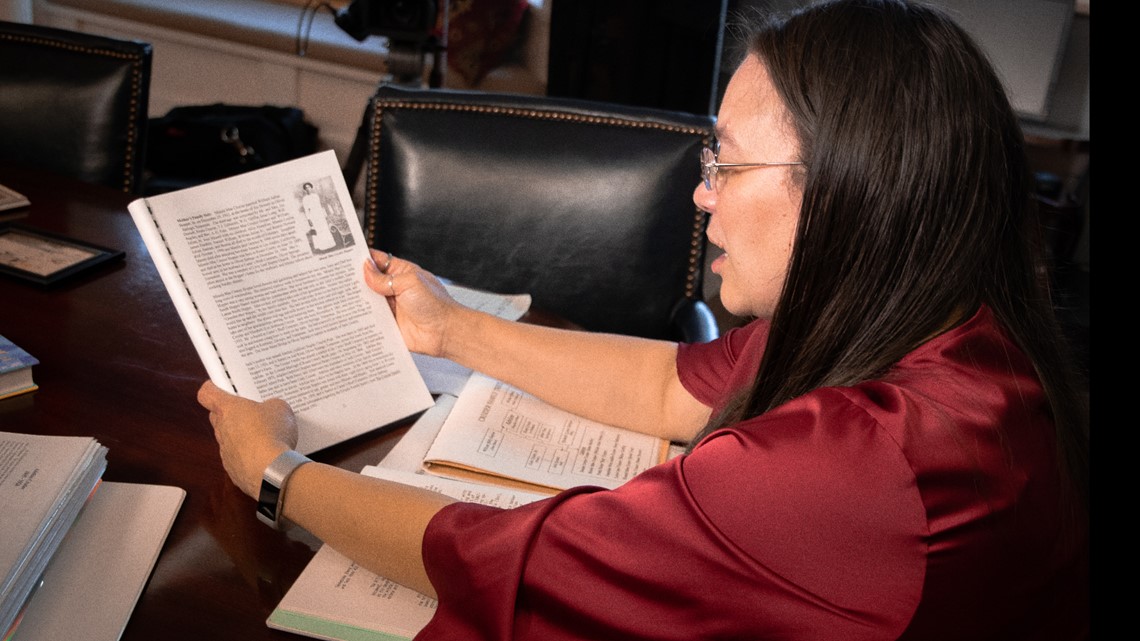

But, as Michele Daniel pointed out, that chapter was just pages ago within the overall novel of human history.

"People think it was so long ago, you know thousands of years ago when Christ walked the earth. It wasn’t that long ago,” Daniel said.

Bringing the lingering trauma of the past more clearly into the present is often an emotional but necessary part of the search.

“On one hand, I'm very proud of how far the family has come and what they’ve accomplished,” Brabson paused. “And, on the other hand, I feel some anger and resentment at what it took to get here."

Resentment because Brabson knows if he and the rest of the Daniel and Dockery descendants do not take it upon themselves to tell the stories of their ancestors who lived here, breathed here, and died here, then no one else will.

A Voice for the Past Subtitle here

The institution of slavery was not one East Tennessee opted out of or largely resisted.

It was a cruel practice many people both engaged in and profited from.

Dr. Tim Baumann is a curator of archaeology at the McClung Center and has researched the daily lives of slaves in this region and throughout Tennessee.

"The mid-South was much different than when you think of the Deep South - of that Gone with the Wind, romantic view of these big plantations with hundreds of African-Americans working on them. You know, in the Upper South, the average number of African-Americans working on a farm or on riverboats would be a handful of people at most," Baumann said.

Baumann also added though many East Tennesseans did not own slaves personally, they still exploited their labor for profit.

"You didn't have to own an enslaved person to have them work for you in urban areas. You have hiring out. So, during the winter months, when there isn't as much work to do on some bigger farms, they can hire out the African-Americans, to go work in industry...or go to mining or work on riverboats and things like that," Baumann said.

BEHIND THE SCENES - Learn from Dr. Tim Baumann as he recounts how archaeologists are able to match African-American oral traditions with things researchers find in the ground to paint a picture of daily life.

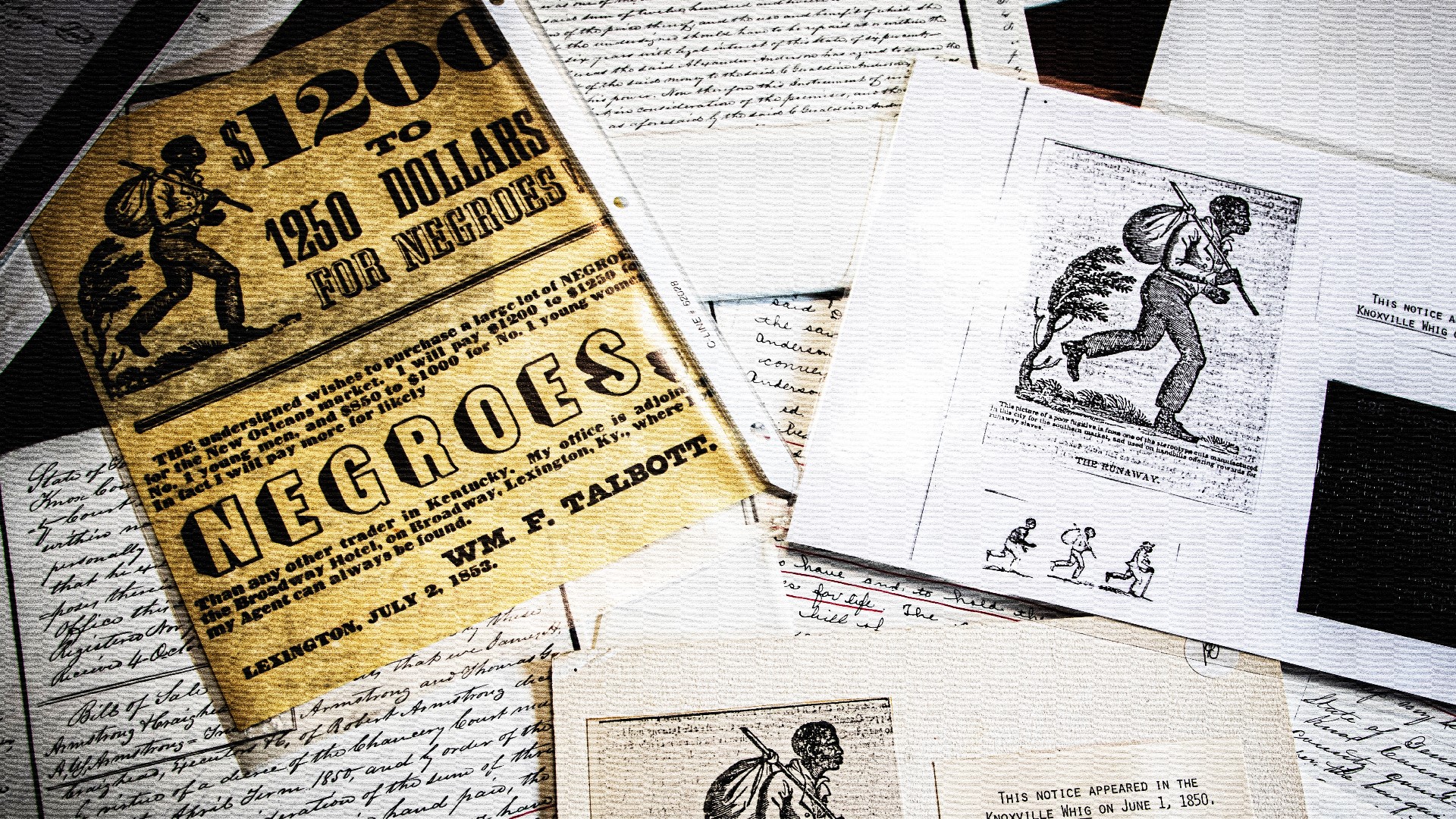

A society that profited so flagrantly off the exploitation of human life was not keen on recording their atrocities.

He said the amount of information the Dockery and Daniel families have been able to uncover is extremely rare.

Because enslaved people were considered property and not human beings, they were not counted in census records in the time period before abolition.

It makes searching for them a daunting task.

“For most families, it’s often impossible,” he explained. “And the only way you can try to do that is if you’re looking at that cusp from the 1860 population census to the 1870s.”

An example of the discrepancy in how much easier it is to track down free people versus people who were enslaved is present within the Dockery family.

Charlotte Dockery, Brabson's great-great grandmother, was a slave to the Thomas family. While the family has traced Isaac's line back to the 1700s, there are still chunks of missing history in Charlotte's family line.

"For a long time we didn’t know who Charlotte’s mother was until we found her in the 1880 census, she was living with Nancy Dockery. We knew her name was Mary and we also found that Charlotte had a sister. Her name was Ally, but that was hard to find," Brabson said.

The New Salem Baptist Church also aided in the family's search because it provided a physical space for stories to be shared, so younger generations could learn from older ones.

Though the internet proved a useful tool in the family's perpetual hunt for history, it will never be the same as the information Brabson uncovered from the stories his grandparents told.

Before their death, he said they blessed him with several starting points.

"You have to know what you're looking for to find it," he said. "Every time a grandparent dies, it's like a library burns down."

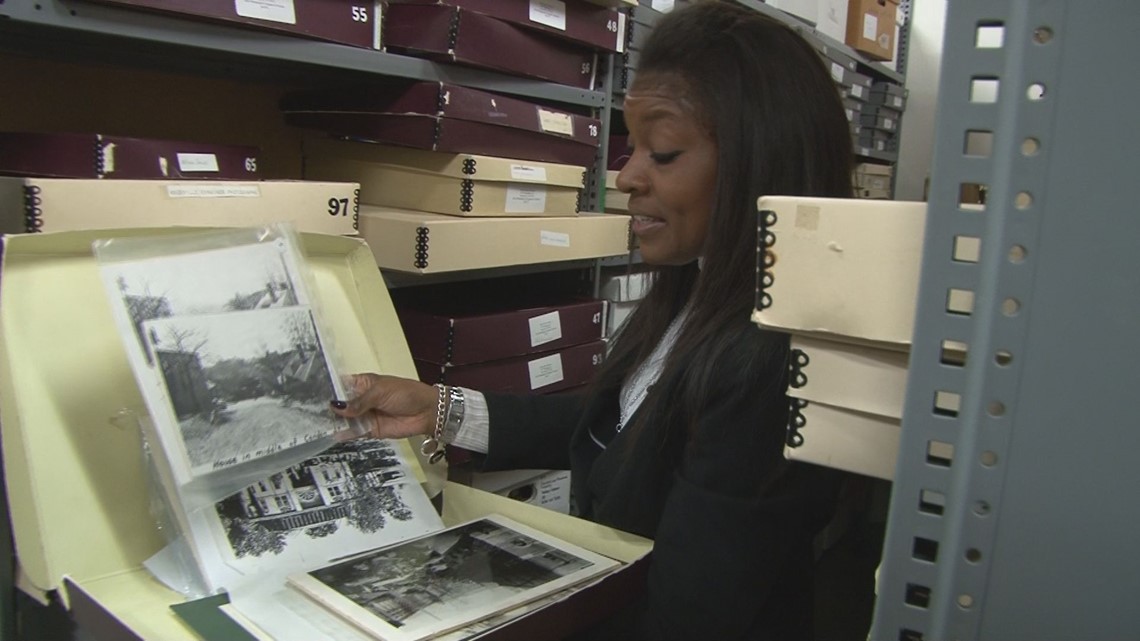

Reverend Renee Kesler is the president of the Beck Cultural Exchange in Knoxville an organization that records, preserves, and manages centuries of African-American history.

She said bereft of written record, oral traditions became crucial for African-Americans in passing down their legacy.

"African-Americans traditionally have to use non-traditional sources to ascertain information. So there's so many broken records in history that much of the African-American story is passed down, because there was no written records through oral tradition. The oral history is very important," Kesler said.

Oral history was also how slaves passed down their culture to their children. And because none of it was written down, descendants may not realize that the particular lesson or story the heard from their grandparents is part of a larger context.

"There are a number of cultural traditions we've been able to connect going back to West Africa. Here in Knoxville, there are some cemeteries we can still go in to and find broken pieces of dishes on people's graves or shells laying on the graves. That tradition is often associated with the deceased person spirit. When you make sure they're at ease and go into the afterlife peacefully," Baumann said.

Even if families can obtain written records, there is also the issue of names which continue to change.

As a way to further suppress the humanity of enslaved people, slavers would force their own name upon name regardless of what that person's true name actually was.

Kesler said it was common practice for slaves to be given the surname of the slavers.

That was the case for Adaline Staples Crozier, Michele Daniel's great-great-great grandmother.

“The name she was given was Adaline. They didn’t care about her last name. Because that last name could change for her," Daniel said.

This erasure in official documentation has sinister implications for how people process the institution of slavery.

For a long time, the people most brutalized by slavery were not the ones telling it's history.

"If there was no voice given to those African-Americans who were, you know, domestic or workers, and they didn't have voices heard, the only story you're going to get is from the people who are either hired them or ones who enslaved them," Kesler said.

"Slavery was here and it was brutal. Period." Subtitle here

In Baumann's research he sometimes sees descendants of slave owners trying to flip the narrative, making room for acts of mercy or empathetic personalities in their ancestral line where they did not exist.

The narrative of the merciful slaveowner persisted for years in many prominent homes across Tennessee. Only now are stories of the cruel side of these great men beginning to be told.

"The reality is, he was a slave owner and had slave houses that were behind his house. He may have been a nice slave owner. But the reality is, he was a slave owner. He was not freeing his own slaves of anything. He was also selling them to his brother-in-law, back and forth," Baumann said.

People often point to pro-Union sentiments that existed in East Tennessee or compare slavery here to what slavery looked like in the Deep South as evidence that the experience of enslaved people was somehow less harmful in Appalachia than other parts of the country.

PART TWO: Her name is Adaline

"Slavery was horrible and there's no way to pretty it up and there's no way to compare it from one in one instance to another," Kesler said.

Focusing on those comparisons not only does a disservice to history, Kesler said, it minimizes the experience of people who were enslaved and suffered here.

"It is a travesty to even use that kind of language. You say simply we had slaves. Slavery is wrong and slavery was brutal. Period. And I don't think you can compare one brutality to another brutality. All of it is shameful. And all of it hurts," Kelser said.

These incorrect narratives make the work the Dockery and Daniel families even more important. With each story told, the families are breaking a cycle of forced silence and intentional erasure.

“Slavery wasn’t just about a physical breaking of the back. It was truly a spiritual breaking as well,” Kesler explained. “Because if I can break you mentally, and make you believe that you are less than - that you are not human - then now not only do I physically have you submissive, but now I have your mind to where you don’t even think you can ever see freedom.”

Since the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, Baumann said there has been a push by families descended from slaves to reincorporate their experiences and stories into the homes and places where they were kept against their will.

From Thomas Jefferson's Monitcello to Knoxville's Blount Mansion, descendants of slaves are working to incorporate an authentic narrative into the space.

"Academically, that's when we start to go away from the white, male, rich history and start talking about popular and social history - the everyday people. There's a lot more history that we don't know," Baumann said.

Diminishing the oppressive and pervasive role white Americans played in slavery is particularly harmful as well, because the effects of slavery can still be felt today in racist housing practices, income gaps, and the discrepancy of mass incarceration rates between white and black people.

There was also lack of atonement for any of these transgressions.

Given that lack of atonement for the atrocities of the past, Baumann and Kesler said it is only possible to learn from it.

"When we know better, we can do better. So we have to look back. Not so you might judge our ancestors, or judge the people who came before us. But we're looking back to learn, so that we can see what happened. Understand what happened, and find a way to ensure it never happens again. That's it," Kesler said.

"I Finally Found You" Subtitle here

In his lifetime, Brabson has not been exempt from the same discrimination his ancestors experienced.

Brabson was in fifth grade when schools were desegregated.

He remembers being excited to learn in a school so big. The thought of the mashed potatoes in cafeteria still makes his stomach rumble.

He remembers, mostly though, how mean the kids on the playground could be.

"Kids can be mean to each other and you're out on the playground, the first words out of your mouth are, 'My daddy said or my momma said.' And it was usually something that would hurt your feelings."

As an adult, knowing the great legacy of who his family was helped alleviate some of the pain of discrimination he felt as a kid growing up in Sevierville.

It can never erase it though.

“There's days I'm very angry, and then there's days I'm kinda sad and I wanna talk to my grandparents"

He chooses though to move forward.

"You realize you can't explain it. So I don't want to think about how hard it was. I just want to think about I finally found ya [sic],” Brabson laughed. “You can run but you cannot hide. I finally found you!”

He and the other Dockery and Daniel families will continue finding more of their relatives. Sometimes they are across the ocean or across the country but, often, they are right here in East Tennessee.

This family will continue to open their arms to descendants.

PART IV COMING SOON ON STOLEN STORIES.

►Make it easy to keep up-to-date: Download the WBIR 10News app now and sign up for our Take 10 Lunchtime Newsletter.

Have a news tip? Email 10Listens@wbir.com, or visit our Facebook page or Twitter feed.