KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — In light of the recent disaster that occurred in Turkey and Syria, this week’s Weather Wednesday is about earthquakes.

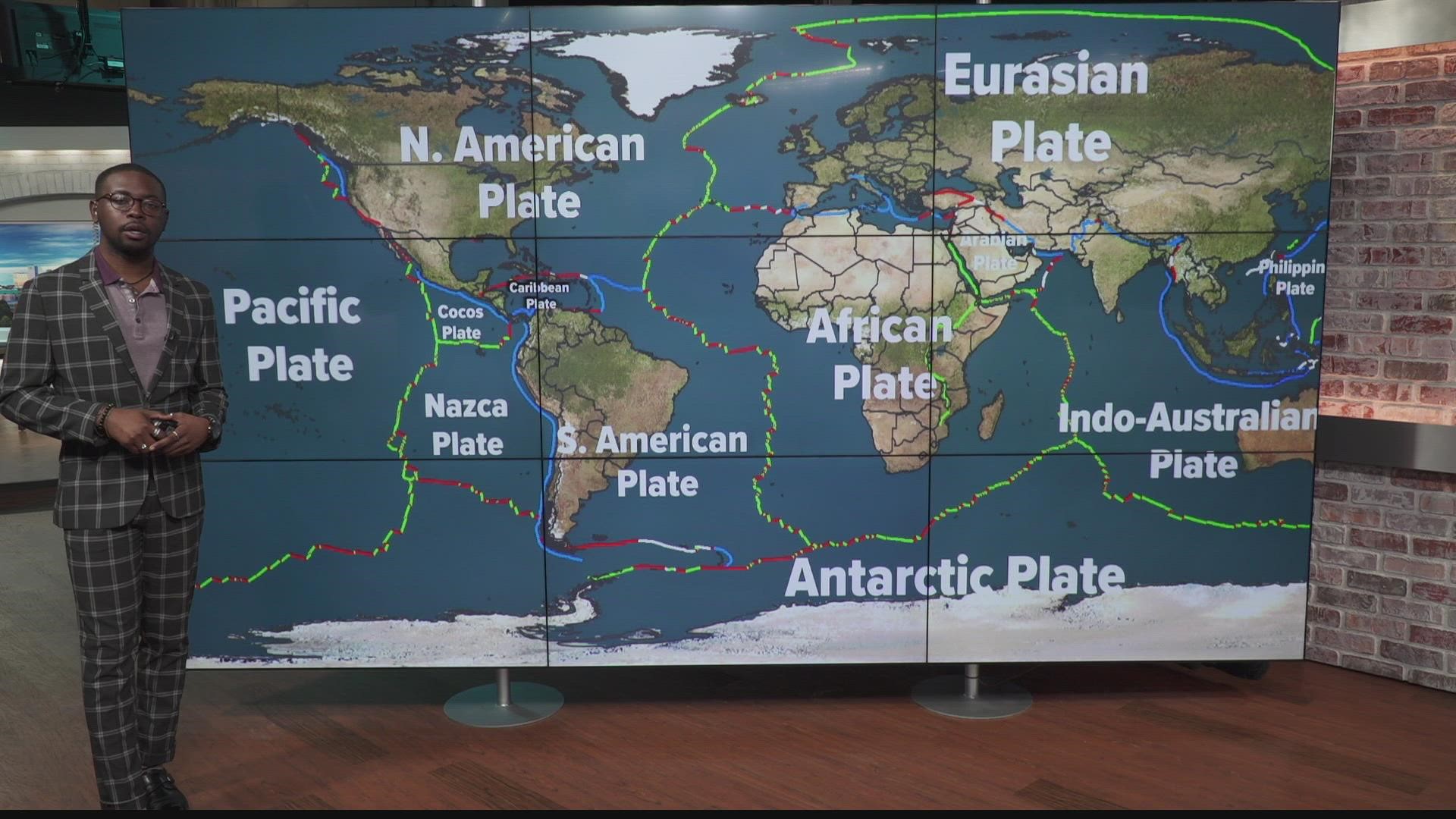

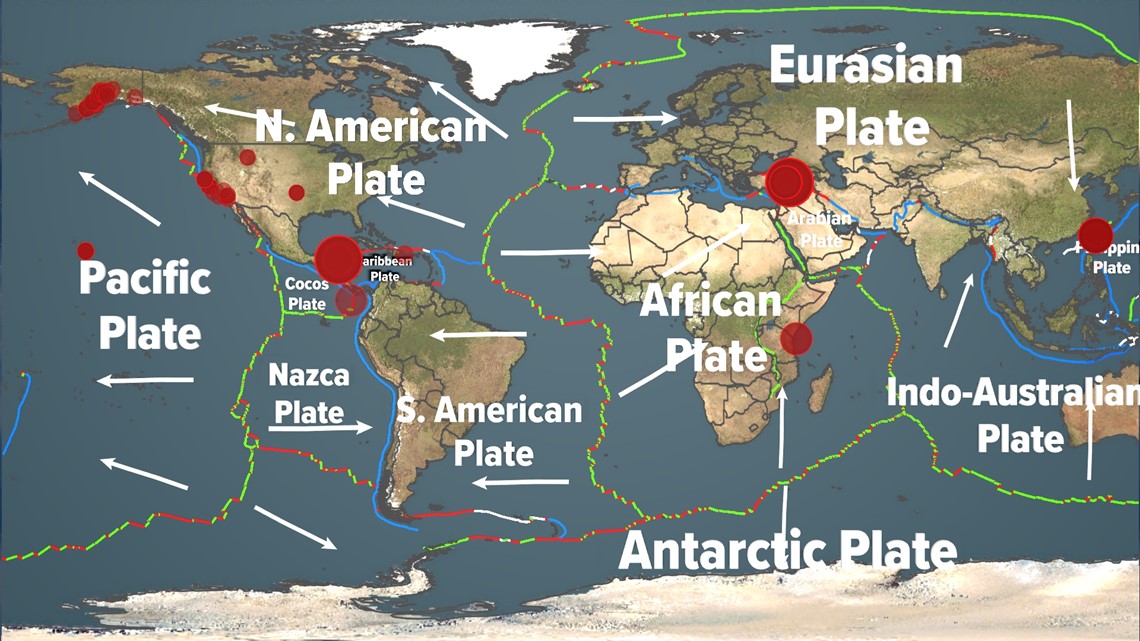

An earthquake is simply defined as shaking of the ground produced by sudden movement of rock material below the earth’s surface. Those rock materials are also known as tectonic plates – giant pieces of the earth’s crust and upper mantle that are constantly moving by a few centimeters per year. Tension and friction build up from these plates interacting with each other, and the release of energy from that movement is where earthquakes are born. All of these plates are separated by fault lines, or substantial breaks in the earth’s surface.

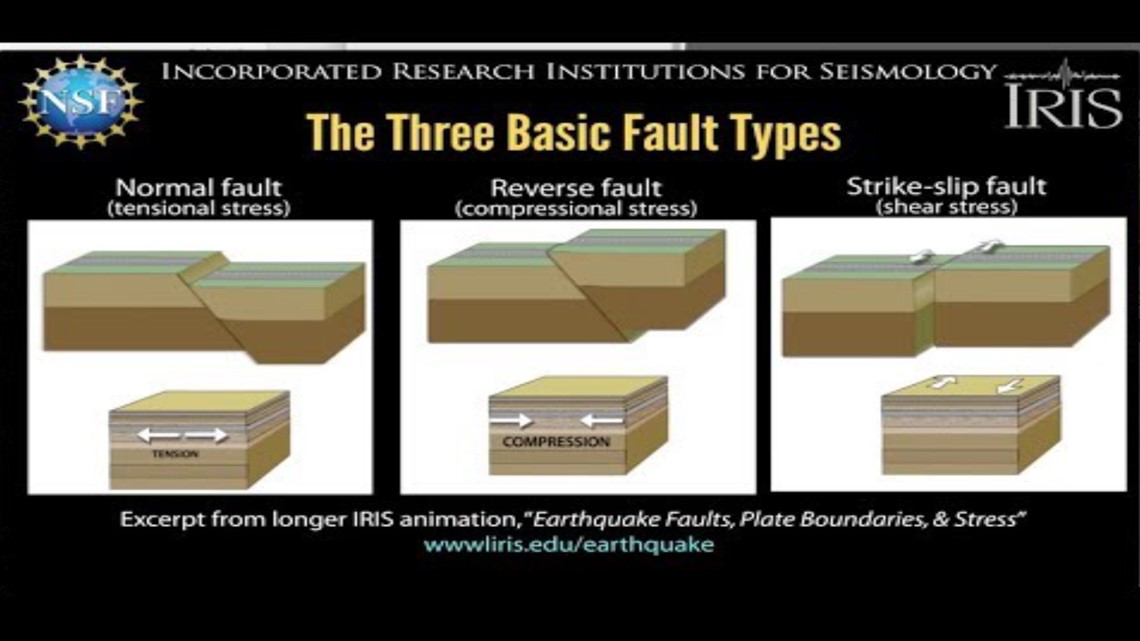

There are three types of tectonic earthquakes. First is a normal fault, where plates moving away from each other build tensional stress. One plate falls below the fault line and the ground is extended. The second is a reverse fault, where plates pushing against each other build compressional stress. This forces one plate to rise overtop of the other and the area is shortened. The third is a strike-slip fault, where a plate moves parallel to another, creating a horizontal force. A strike slip-fault is the type that occurred in Turkey.

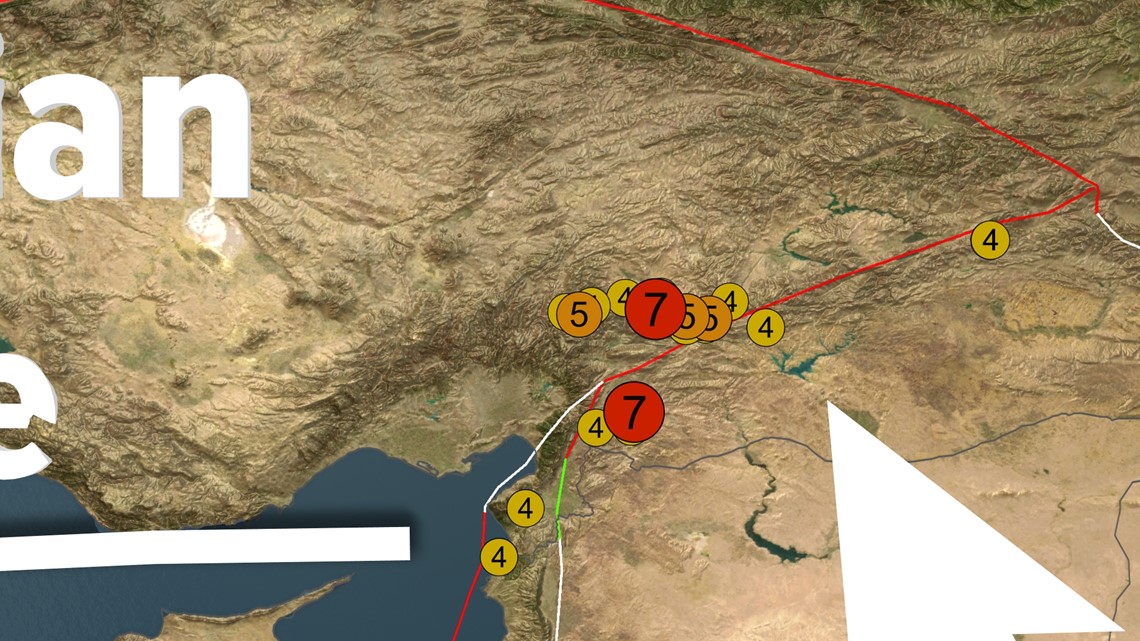

What happened to Turkey and Syria is, unfortunately, just a factor of their geography. The country of Turkey lies on the Anatolian Plate, a conversion point between the African, Arabian and Eurasian plates. Because of this, the area is surrounded by a complex fault line system that is known to be one of the most seismically active regions in the world. Back in January 2020, they had a 6.7 magnitude earthquake cause significant damage. Before then, landmark earthquakes in 1939 and 1999 took the lives of almost 50,000 citizens combined.

The first earthquake struck in the Turkish province of Kahramanmaraş around 4:17 a.m. local time. This initial quake had a magnitude of 7.8 and was said to last between 60 to 75 seconds. There were many immediate aftershocks and victims say the ground was shaking for nearly two minutes. There were over 100 aftershocks in the 36 hours after the first earthquake. Three of those had a greater magnitude than 6.0. Eleven minutes after the first earthquake, a 6.7-magnitude aftershock went off. Another happened nine hours after the first earthquake with a magnitude of 7.6 – nearly just as strong as the first. Tremors were said to be felt as far away as Jordan, Israel, Lebanon and Iraq.

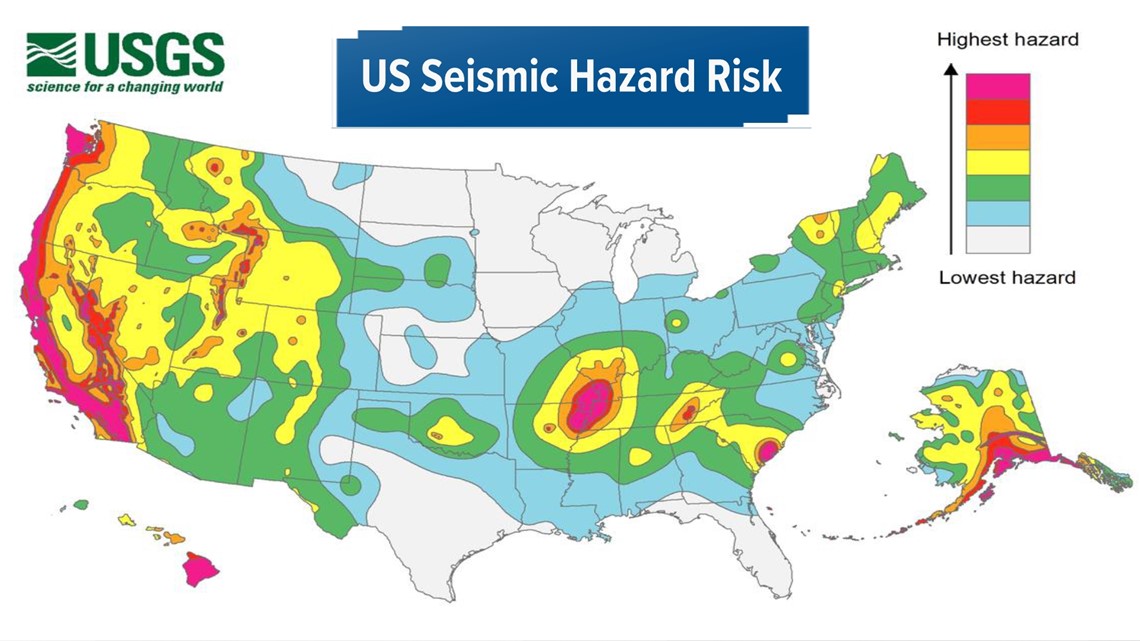

Now can this happen here in the U.S.? Yes, it can. The West Coast, especially California, has the potential to see an earthquake very similar to what’s happened in the Middle East. The San Andreas fault, popularized by the movie “San Andreas” starring The Rock, is a strike-slip fault line just like the one in Turkey.

But the true danger of earthquakes isn’t the literal shaking of the earth – it’s the destruction of infrastructure that it causes. Most earthquake-related injuries and deaths result from collapsing walls, flying glass, and falling objects caused by the ground shaking. With that in mind, the West Coast has very strict earthquake-resistance building codes that help separate buildings from the ground.

Earthquakes can still happen in locations that don’t have a major fault line nearby. They’re just generally not as strong. The most widely-felt earthquake in U.S. history, striking in August 2011, had its epicenter in Mineral, Virginia. It was a 5.8-magnitude quake that even caused damage to the Washington Monument over 90 miles away.

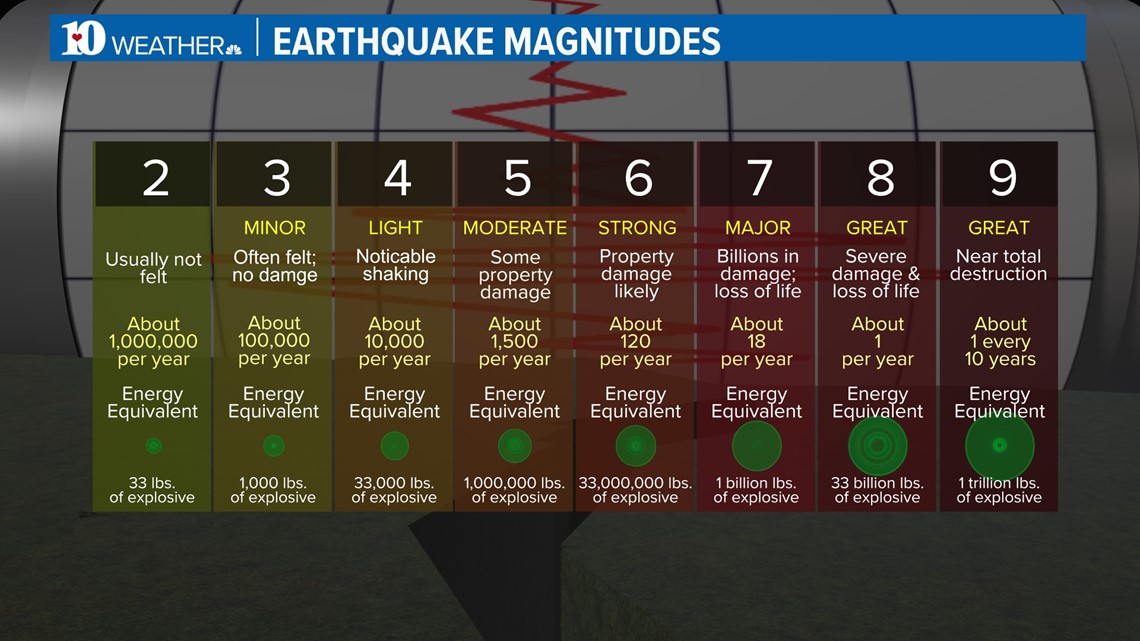

One last thing to note: the earthquake magnitude scale does not increase incrementally. Magnitude is measured in whole numbers and decimals using a logarithmic equation. This just means it analyzes a large amount of data in a compact form. So, for example, a quake of magnitude 7 is not one degree greater than a magnitude 6. It’s actually ten times greater.