KNOX COUNTY, Tenn. — East Tennessee saw some severe weather as we started the second week of May, which caught many by surprise.

One threat we saw plenty of was lightning, and we were not alone. Videos of spider lightning and consistent strikes in the Midwest were circulating around social media this week. So where does lightning come from, and how do we interpret it properly?

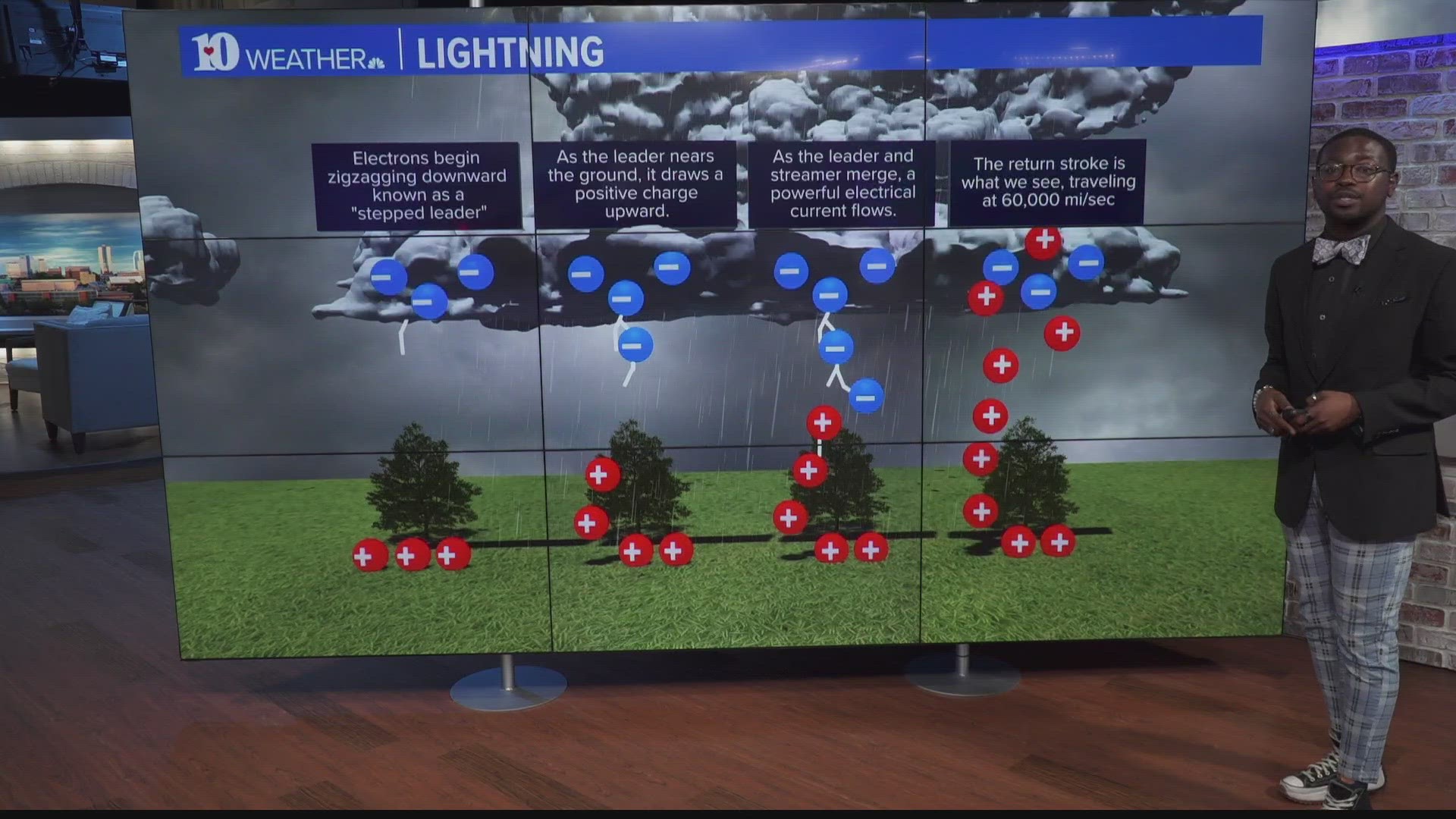

We'll start by taking it back to chemistry class - it all starts with protons and electrons. Electrons in the storm clouds begin to reach toward the ground, becoming a stepped leader.

Protons on the ground notice this, and since opposites attract, protons start to reach up to the sky. If you were about to get struck by lightning, this would be when your hair starts to stick up.

Once the protons and electrons connect, the current is formed that will become the lightning strike. This moving current happens multiple times as flashes, or what we recognize as a lightning strike.

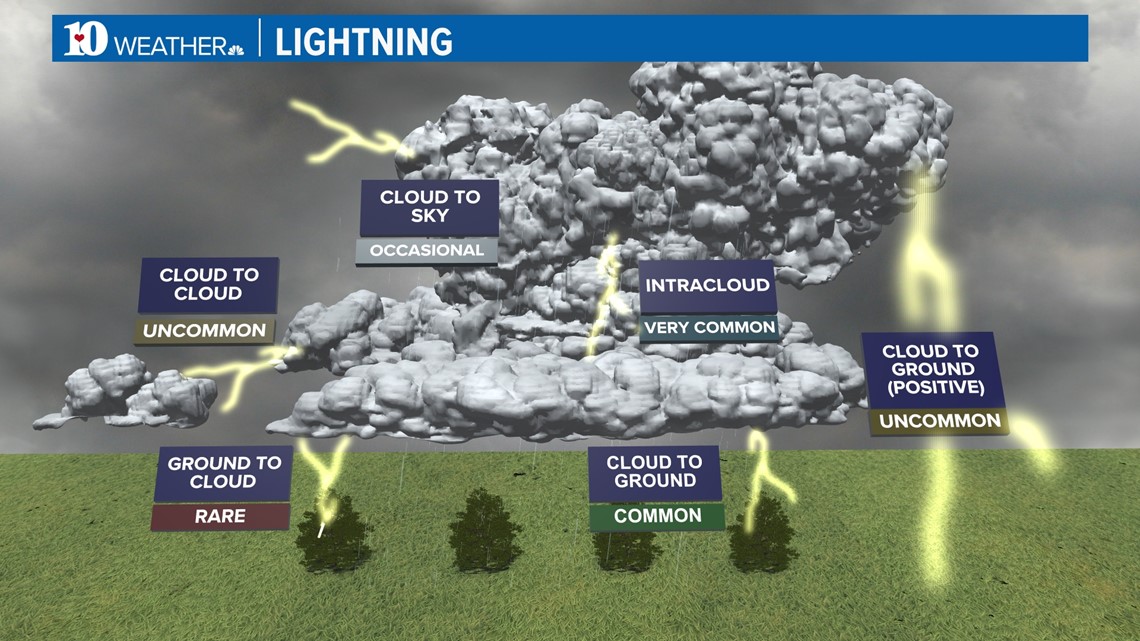

There are many different types of lightning, but the most common that we see are strikes within a storm cloud, or a cloud-to-ground strike.

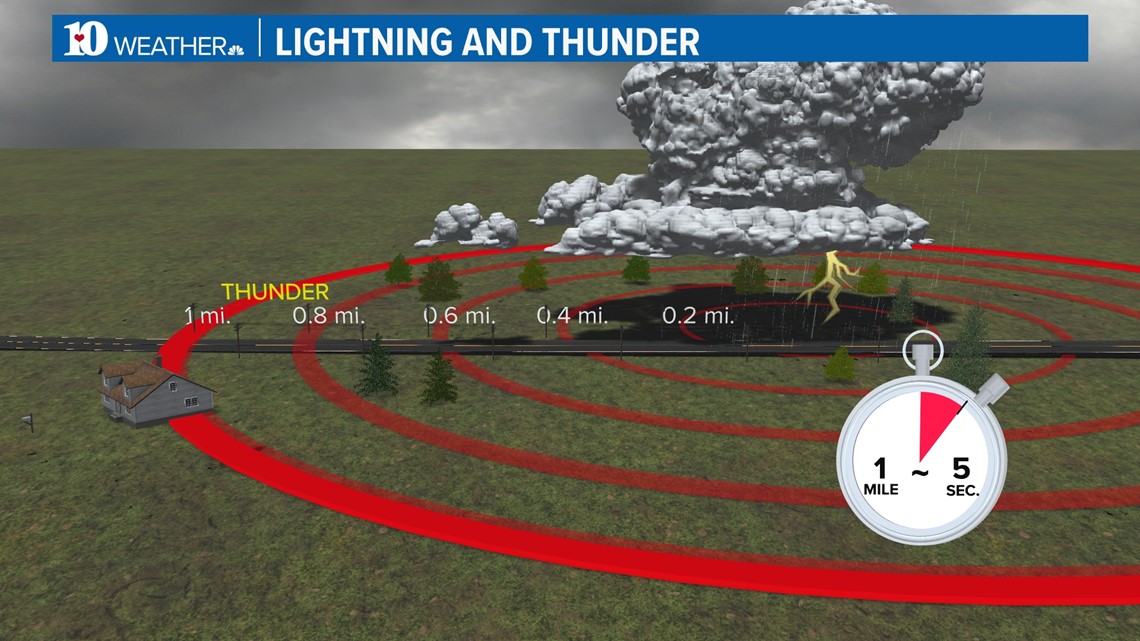

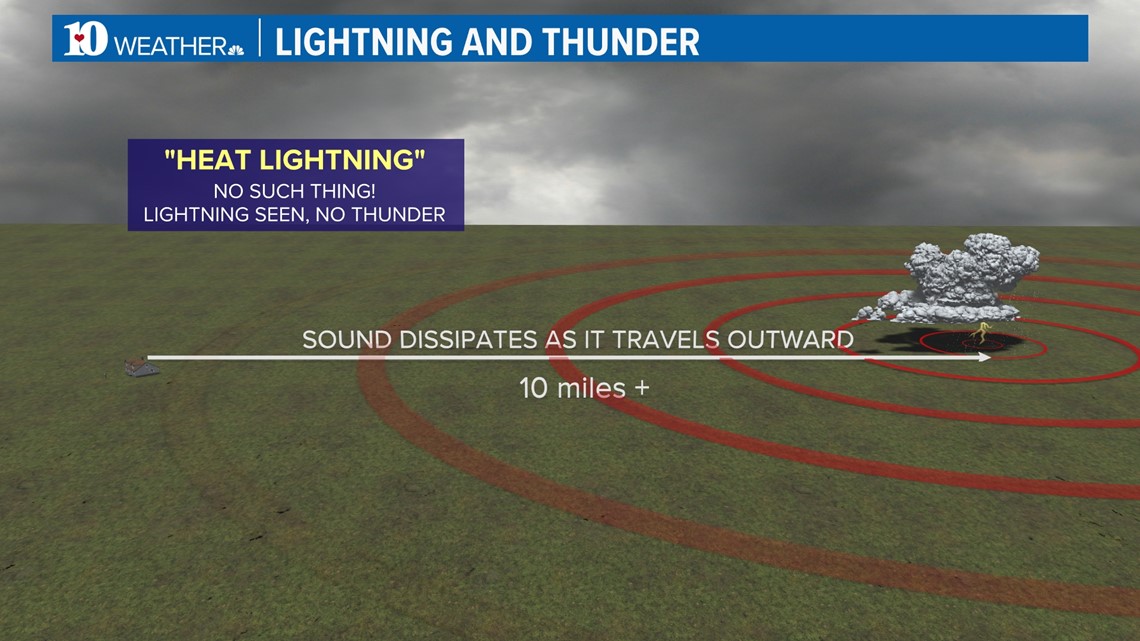

Now factor in thunder, which many use to determine how far away a flash of lightning or a storm are. A clap of thunder will travel a full mile in just five seconds. So doing the math from that point, just divide the seconds you waited by 5 to see how many miles away you are.

However, that sound begins to fade upwards of 10 miles. There's a point that you can see lightning but not hear it. Many have called this "heat lightning" but that actually doesn't exist. You were just too far away to hear the thunder, which could be a good thing!

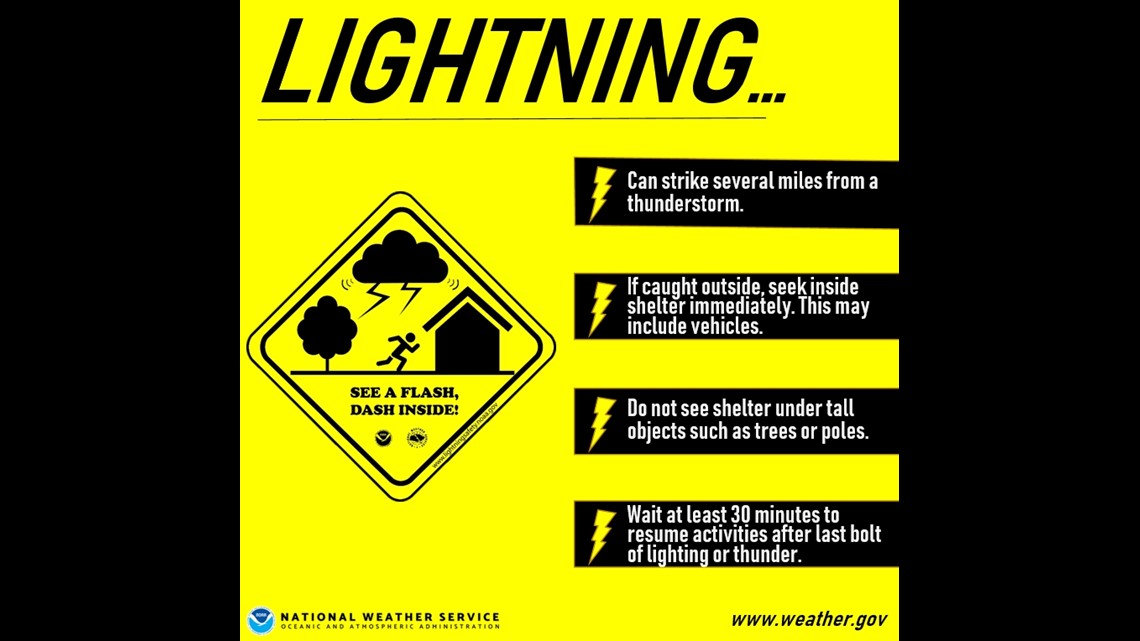

When it comes to safety, there are two popular sayings: if thunder roars, head indoors; and if you see a flash, do the dash. No matter what, just head inside when severe weather is coming your way.