KNOXVILLE, Tennessee — Neil Armstrong made the first footprint on the Moon. Tennesseans helped him get there.

As America pauses this month to remember the historic achievements of the Apollo 11 space mission, people in the Volunteer State have much to be proud of.

Many Tennesseans contributed to the 1969 mission – from helping test the giant Saturn V rocket that would propel astronauts Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins into the moon’s orbit to building the boxes the astronauts would use to collect moon rocks and creating the scoops they’d use to collect moon dust.

When President John F. Kennedy challenged the nation in 1961 to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade, he created a sense of urgency. America had to beat the Soviets, who had already launched the first human into space. The presidential message: The Russians couldn’t beat us again.

Landing a man on the moon – no sure thing - became a national objective. Hundreds of thousands of Americans ended up contributing to the Apollo program.

Fifty years later, it remains one of man’s greatest achievements. We walked on another world.

“The people here in Oak Ridge who actually worked on the project knew the importance of what they were doing, and they were proud to be part of the Race to the Moon. It was something they felt very patriotic about, and it was very important to get done,” said Y-12 nuclear weapons complex historian Ray Smith.

From University of Tennessee-trained scientists and engineers to self-taught draftsmen and machinists, Tennesseans from all walks of life made their mark on the space program. Even a seamstress toiling away in an Oak Ridge sewing shop.

WIND TUNNELS

It doesn’t get as much attention as some of the other aspects of the Apollo program, but a Tennessee installation played a key role in studying the aerodynamics of firing a rocket into space.

The Arnold Engineering Development Center is located near Tullahoma, Tenn., in Coffee County. In the 1960s, engineers there put mock-ups of rocket models into the various wind tunnels on site.

“Anytime you put somebody on top of a rocket, it’s worrisome,” said Dr. Bill Baker, test operations technical director. “It looks so easy, but it’s not, and we did have some tragedies. That just shows that flight tests and flights on something like this are very dangerous.”

As a young engineer always fascinated by rockets and airplanes, Baker couldn’t get to Tennessee fast enough. He arrived in the mid-1960s with testing well underway for the Apollo program.

Scientists ran multiple tests on multiple pieces of equipment. Arnold is known for its propulsion wind tunnels and test cells. Wind tunnels are a basic way to see how something will react while aloft, a method crudely used by the Wright Brothers going back to the early 1900s.

Every part of the Apollo system went through tests at Arnold, from individual parts of the vehicle to the space ship itself, Baker said. The idea of formal testing was relatively new, having only begun at Arnold in the early 1950s.

“They said that if the rocket were to malfunction, it would have the energy equivalency of a small atomic bomb,” said Randall Quinn of Arnold’s Rocket Propulsion Test League. “So, you’ve got three guys riding this thing. You’ve got to make sure it works. An extensive amount of testing had to be done.”

The very first thing Baker worked on at Arnold was the dynamic stability of Apollo’s escape module, the capsule astronauts would have to use if they faced a sudden, dire emergency.

Scientists also studied how the upper stages of a moon rocket would react as well as the motor for the lunar module, one of the last stages of the planned moon mission.

Not surprisingly, those who worked at Arnold during Apollo think they played a key part in the mission’s fundamental success.

“We pretty well feel like we put the people on the moon. All of the aerodynamics were tested here,” said Baker, looking back.

It’s a sentiment shared by the hundreds of thousands of people who worked on Apollo as well as its precursors, the Mercury and Gemini programs. It became part of the Apollo culture: Every person was expected to do their very best to contribute to the program’s success.

THE MIGHTY SATURN V

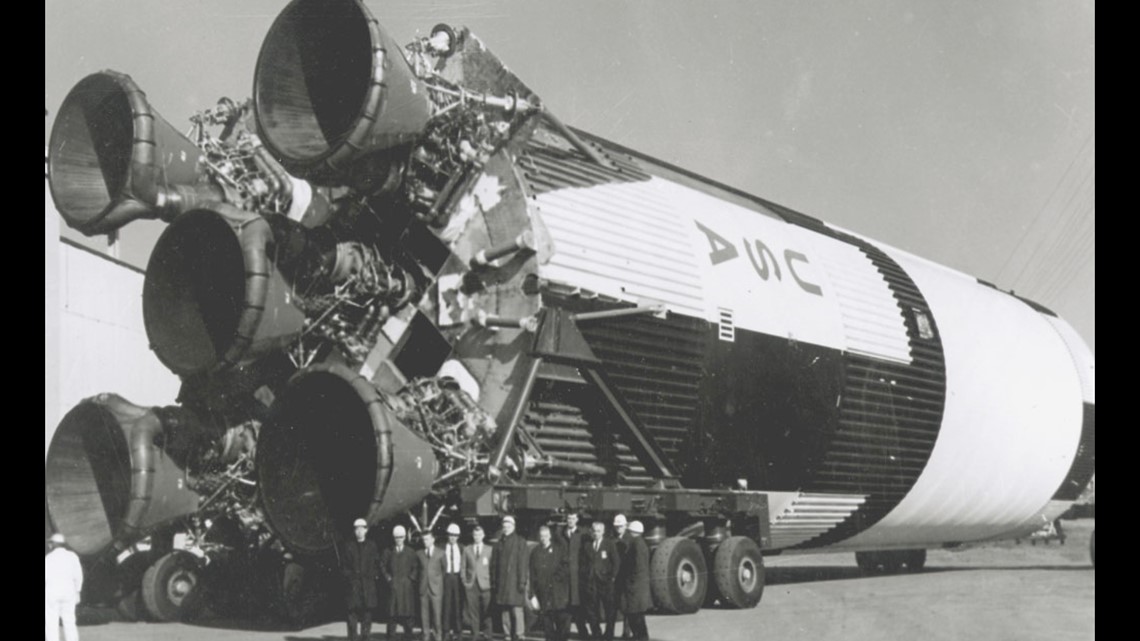

It’s all fine and good to talk about going to the moon. But you’ll never make it if the rocket isn’t big enough.

NASA already had sent many men into orbit on smaller rockets for Mercury and Gemini. But for Apollo, the space program had to create something so big it could travel several days to the moon and then come back.

At 363 feet – taller than the Statue of Liberty – the Saturn V was the answer.

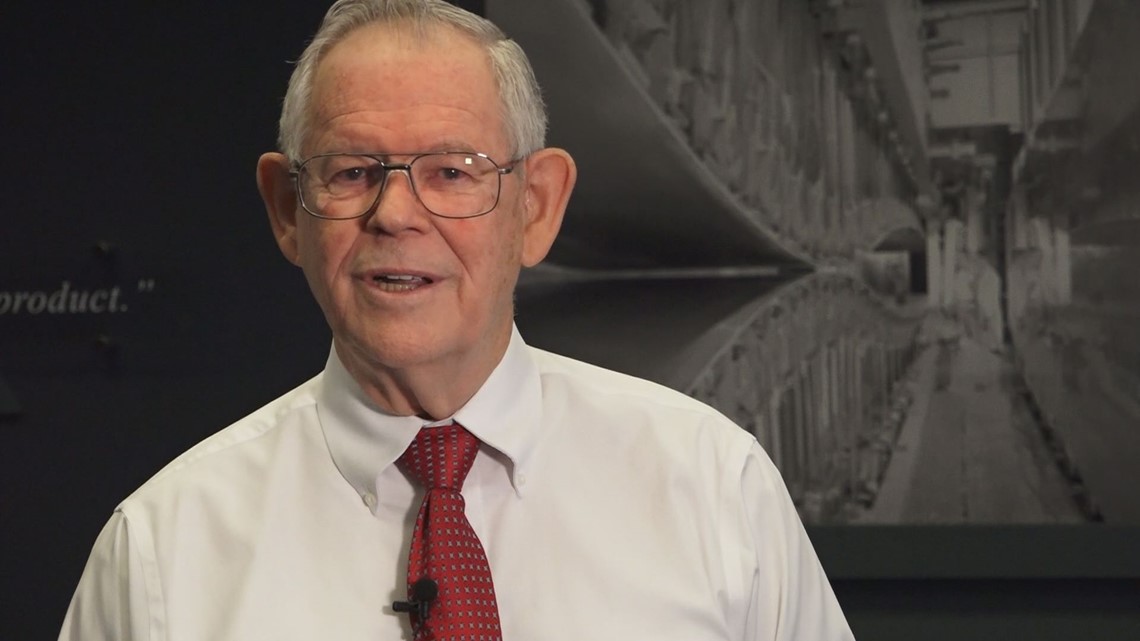

Tennessean Parker Counts was among the team who worked in the 1960s testing Saturn V in Huntsville, Ala., at the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center.

He arrived in Huntsville in 1963 after graduating with an engineering degree from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. Counts was among the scientists working under German-born Wernher von Braun, one of the world’s pre-eminent experts in rocketry.

“The biggest challenge was to escape gravity, and we understood it needed to be the biggest engine,” said Counts, now retired and living in Chattanooga.

Counts was part of the test crew, seeking out both failures and successes to identify any possible problems with the giant rocket.

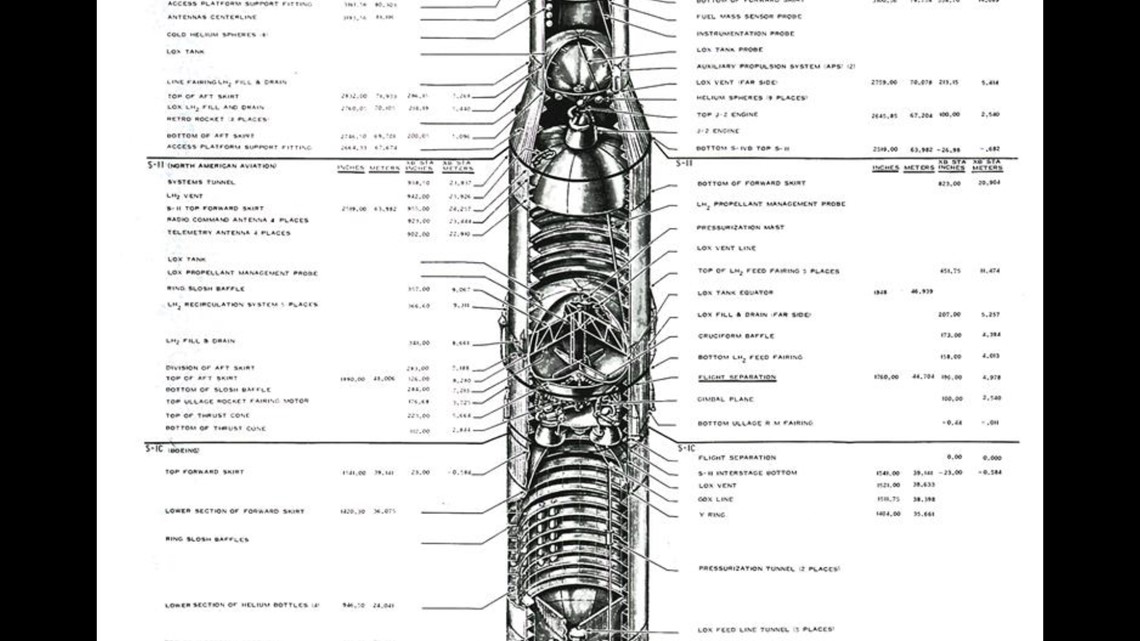

The Saturn V had three stages.

The first featured five F1 engines capable of generating a total of 7.5 million pounds of thrust, Counts said. Stage one lasted about 2 minutes, designed to propel the giant payload beyond gravity.

The second stage had five J2 engines to maintain course. The third stage had a J2 engine that allowed it to circle the earth and motor onward to the Moon.

The responsibility was enormous. It was something crews didn’t dwell on.

“We didn’t really have time to worry about anything,” Counts said. “We just did it.”

William Vaughan also was part of the team in Huntsville. He’s a NASA emeritus and also a UT engineering graduate.

The culture, fostered by von Braun, called for everyone helping each other to ensure success, he said. Everyone involved, Vaughan said, knew they were working on “their” rocket.

“There was none of this, ‘Well, we’re not going to tell them what we’re doing,’” he said. “So that made a difference in the Saturn V, and it’s one of the reasons we never lost one.”

Marshall Flight Center historian Brian Odom said people did whatever was necessary to ensure the Saturn V succeeded, including working extra, unpaid hours.

“They’d bring a sleeping bag and a pillow, and sleep in the office, and wake up, solve a problem and then go back to sleep, before waking up again and solving a new problem,” he said. “This (Apollo) had never been done before. There were no textbooks.”

It was the stuff of science fiction. But it was really happening.

The tragic launch pad fire in January 1967 during testing of Apollo 1, which killed three astronauts, only propelled everyone to work harder to achieve the mission.

Apollo 4, the first, unmanned launch of the Saturn V in November 1967, was flawless, Odom said. But the next unmanned Saturn V launch, Apollo 6, in April 1968, had multiple problems, he said.

It left NASA teams with only eight months to get things absolutely right before the first manned flight aboard a Saturn V. Rumors persisted that the secretive Soviets might actually be planning to send a man to the moon. Apollo pushed on.

Apollo 8, as it turned out, went perfectly, in December 1968, sending a crew out toward the moon.

By July 1969, everything was in place for Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins to blast off from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Parker Counts, born and raised in Tennessee, was there on that hot, muggy morning as a spectator.

“We were confident in the launch vehicles and all the things, but the one unknown was that we were going to land a man on the moon and that had never been done. So that’s where the pucker string gets a little tight.”

Counts, his wife and their 2-year-old spent the night like thousands of other people along the Florida coast, awaiting the 9:32 a.m. launch.

And then it went up.

“It was amazing,” he said.

A BOX, A SCOOP, A POUCH, A PAD

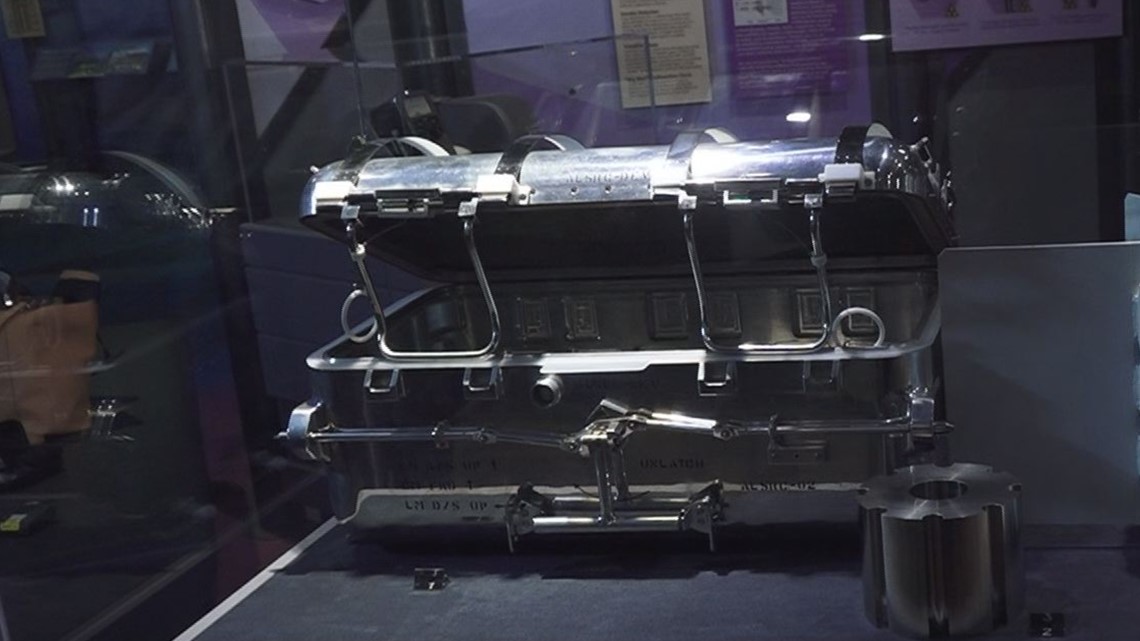

From 1969 to 1972, the duration of the Apollo moon launches, astronauts brought back more than 840 pounds of lunar material. Every bit of that came back in a box made in Oak Ridge.

NASA’s goal with Apollo was not only to land people on the moon, but to collect rocks and dust for study.

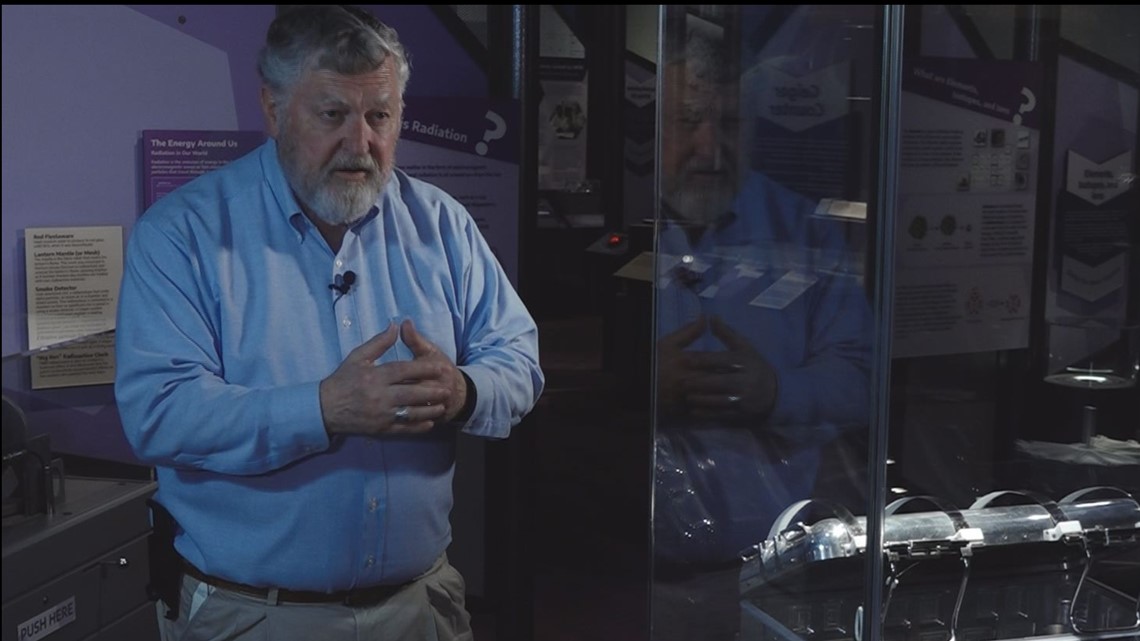

“There is a lot that can be learned from the materials of the moon, the origin of the moon, what it’s made of,” said Y-12 historian Ray Smith. “It’s not cheese.”

Y-12, where nuclear weapons components are reconstituted and disassembled, became involved because of its machining capabilities, according to Smith.

NASA needed a leak-free box with no seams that would protect the lunar samples, said Paul Wasilko, director of program integration for CNS Y-12.

“How could you get them back to Earth and not contaminate them with Earth’s atmosphere, oxygen and nitrogen in the air? And, more importantly, how could you protect Earth from the samples?”

Y-12 machinists made the NASA moon boxes – more than 16 -- from a solid piece of aluminum. They featured three seals and four straps to ensure they wouldn’t open unexpectedly. They also were made to accommodate astronauts wearing heavy, protective gloves on the Moon’s surface.

The Apollo 11 crew went up with two boxes and came back with more than 50 pounds of rocks and lunar samples, said Wasilko.

Y-12 today has a box that made the trip. The American Museum of Science and Energy in Oak Ridge also displays one, although it didn’t go to the moon.

Smith said the moon boxes meant a great deal to those who worked on them.

One man, in fact, later asked that a box be present at his funeral, he said.

“I arranged for that to be there because it was the thing he was most proud of,” Smith said.

But the box wasn’t the only thing made here in Tennessee. Pouches used to hold specific samples also had to be fashioned for inside the moon boxes along with protective pads to cushion the moon rocks from being jostled and damaged during the return flight.

For that, planners turned to a small business – now gone – in Oak Ridge called the Knitting Nook.

Working with lightweight, fire-resistant Teflon, several women including a seamstress named Lorene Shook of Oak Ridge knitted some 40 pads to wrap around the samples. They cost $7 each.

Shook’s granddaughter, Krista Deal, later attended the launch in December 1972 of Apollo 17, the last trip of the mission. On board were some of Lorene Shook’s Teflon pads.

But East Tennessee had yet more to contribute to the moon mission -- in the form of a soil or “moon” scoop.

Draftsman Glenn Ellis of Lenoir City worked for Union Carbide at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. He was tapped to come up with a design for a “contingency soil sampler,” a device to collect soil from the Moon’s surface.

“The way I remember him telling it, everything the astronauts had when they first exited the module on the Moon had to be on their uniform,” said Michael Ellis, the son of Glenn Ellis, now deceased. “They couldn’t carry anything. Any tool they used had to be on their uniform.”

NASA wasn’t sure what the astronauts would find once they landed on the moon’s surface, so they wanted Armstrong and Aldrin to grab a quick bit soil with Ellis’s scoop as soon as they got out. That way if they suddenly had to bolt they’d at least have a little bit of the moon to take back home for study, said Kevin Gaddis, an Ellis grandson.

History would show the astronauts failed to follow protocol in that regard.

After the Eagle landed on July 20, 1969, the astronauts decided to take some pictures first with a special Hasselblad camera they’d brought. Then, they used Ellis’s scoop to get some soil.

The sampler gained a bit of unintended fame later on Apollo 14 thanks to astronaut Alan Shepard.

One of the original Mercury astronauts, Shepard snuck the head of a 6 iron golf club on the Apollo flight. When he got to the Moon, he attached it to the Ellis scoop.

“He had the help of some other engineers and technicians so he wouldn’t get detected,” Billy Galyon, another Ellis grandson, recalled. “When he got to the Moon, he was able to attach the head of that 6 iron, drop two golf balls on the surface and hit both of them where he famously said, ‘Miles and miles and miles.’”

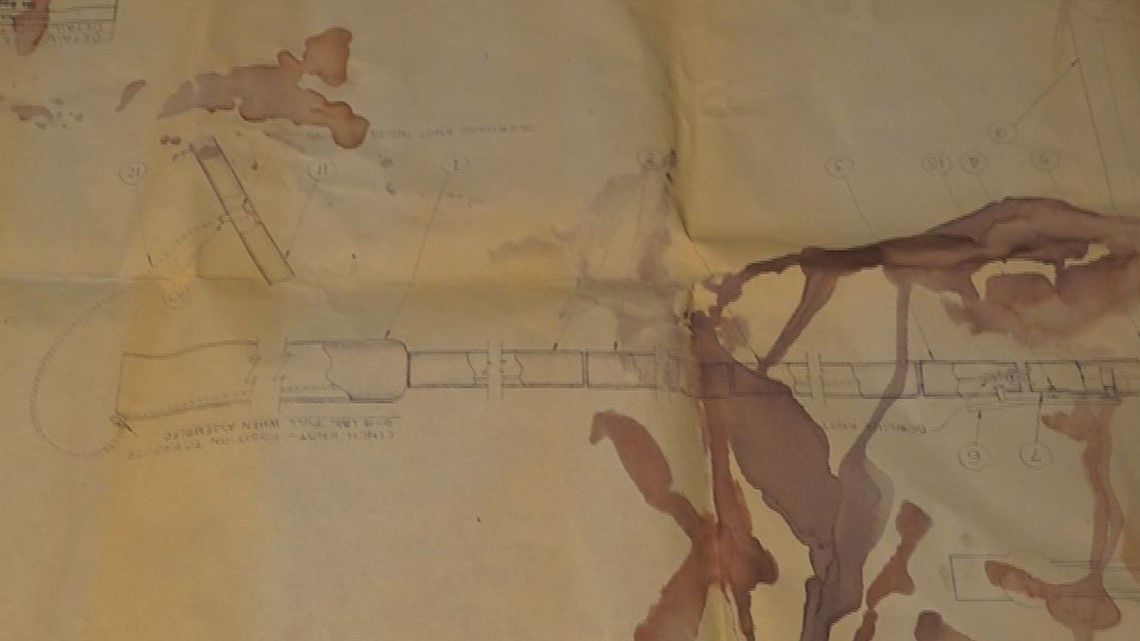

The Ellis family still has Glenn Ellis’s coffee-stained blueprints for the moon scoop, along with numerous Apollo mission photos, a gesture of thanks from NASA.

When he was a boy, Michael Ellis didn’t think much about what his father was doing. It was only later, after he became a man, that he fully understood and appreciated his father’s contribution.

Glenn Ellis’s role also gives the family a unique bond, Michael Ellis said.

“We all love to look at these pictures (from NASA) and go out and look at the Moon, so to me that’s the bigger story is the impact that something my dad worked on touches the family the way it does.”