Knoxville's Forgotten Champion: Big John Tate

Knoxville is a city built on sports from the Vols to Olympians to Hall-of-Famers. One world champion, however, has been lost to time. This is his story.

“In this corner, from Knoxville, Tennessee, Big John Tate!”

On October 20, 1979, in front of a nearly all-white crowd of over 80,000 in segregated Pretoria, South Africa, a 24-year-old Black man from Knoxville named John Tate found himself in a boxing ring preparing to battle for the Heavyweight Championship of the World. The same title that was recently vacated by the greatest of all time, Muhammad Ali.

His opponent: undefeated South African hometown hero, Gerrie Coetzee.

Tate was a long way from his home in East Tennessee and an even longer time removed from the cotton fields of Arkansas where, as a teenager, he labored under a system built on oppression.

Big John's Beginnings

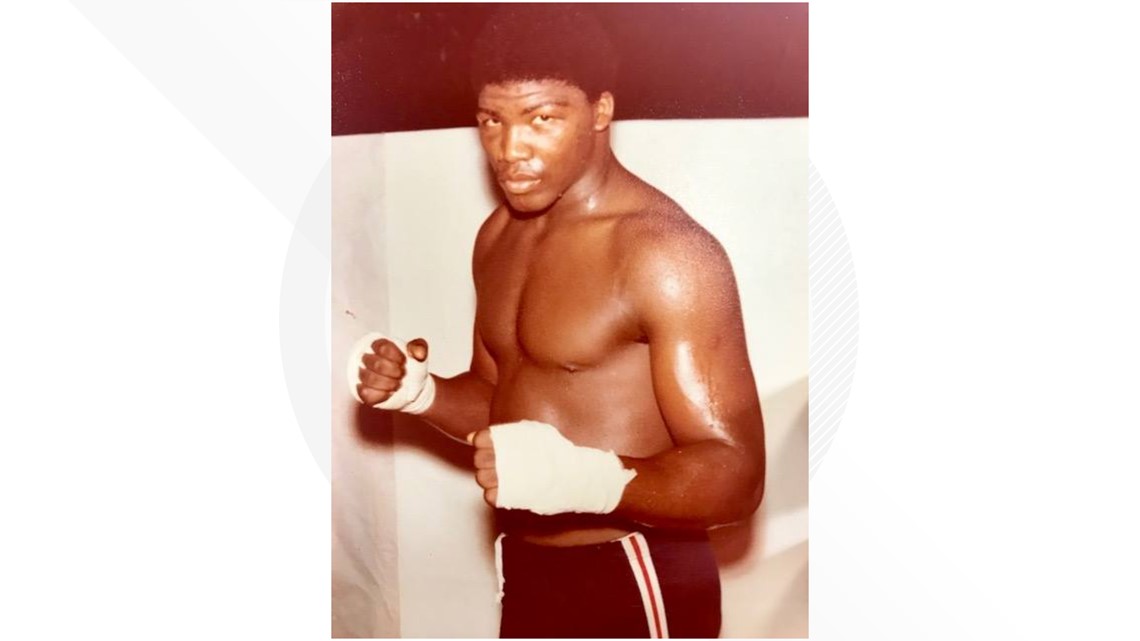

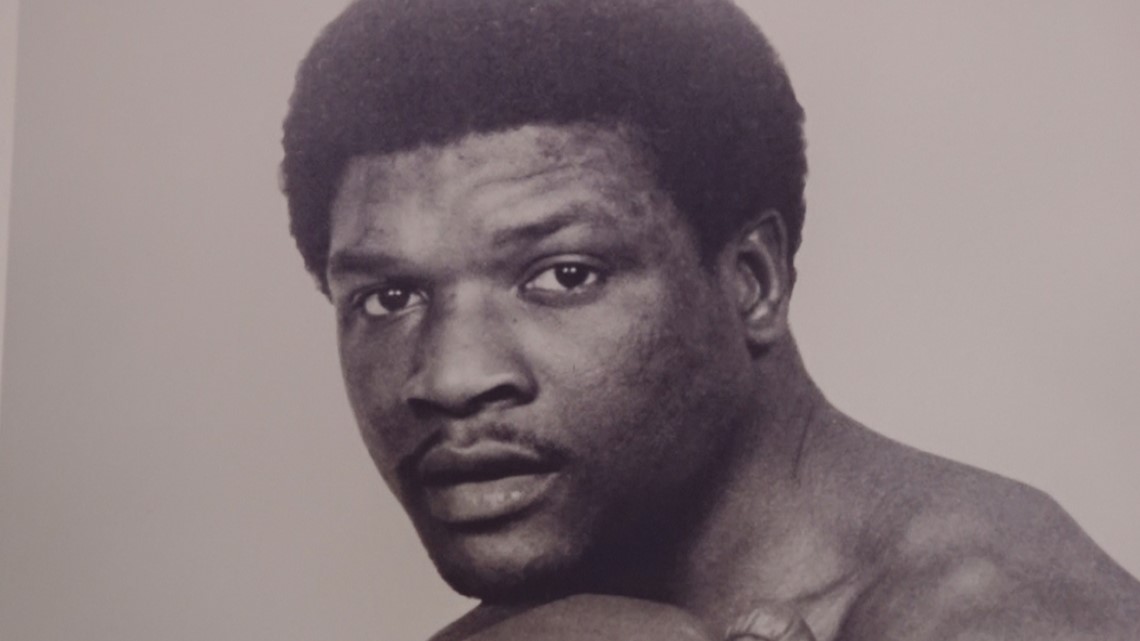

In January 1955, Big John Tate was born into his nickname.

“That boy weighed 16 pounds, 16 ounces. Cost me 29 stitches,” his mother, Vernice Tate Brown Archer, said in a 1979 Knoxville News-Sentinel article.

The second of seven children, Tate’s father skipped out at an early age, leaving his mother and grandparents in charge of his upbringing. In moments when they couldn’t be there, in stepped their neighbor, Alberta Patton.

“He’d say, ‘Miss Alberta, I’m gonna make you real proud of me.’ He’d tell me how he would have a big car and lots of money,” Patton told reporters in 1979.

Wealth, however, seemed like a distant dream. According to his grandmother, Leona Gamble, there were times in Tate’s early life when he didn’t even have clothes on his back. His peers took note.

“We were poor folks, but his family was really poor and John couldn’t talk good,” a classmate said in 1979.

Speech therapy was another challenge, but those programs weren’t an option at the all-Black schools Tate attended.

“They didn’t take notice of kids with special problems. They’d just say, ‘Boy, you learn,’” Patton said.

He also could not read or write, and his size often left him the victim of ridicule, especially as it caused him to be bumped from the fourth grade directly into the seventh.

“I found John to be much taller and larger than the other kids in the class, and therefore, his size created a problem for him. Difficulty in getting along with the other students because of his size,” Mrs. Johnson, Tate’s sixth grade teacher, told reporters in 1979.

Tate eventually dropped out of school and took on jobs like loading livestock feed, hauling lumber and picking cotton.

Without a father figure, Tate looked up to his uncle, Leroy Gamble, who never shied away from a fight.

“He wanted to grow up and be like me. I told him, ‘No, that’s not the way’ because I used to do a lot of street fighting, and I didn’t want him to grow up like that,” his uncle said in 1979.

Despite the warning, Tate followed his uncle’s lead, and one of his many street brawls ended with a stab in the shoulder. A minister who visited him in recovery offered Tate both a vision and a tangible future saying, “as much as you love to fight, you ought to try boxing.”

This time, Tate took the advice. Within months, he found a coach named James House and started his amateur boxing career.

“All arms, legs and teeth. He was polite and had a wonderful smile. I saw him from the beginning as a good human being. If he was any kind of hoodlum, I wouldn’t have had anything to do with him,” House said in a 1979 News-Sentinel article.

The pair had their first bout in Osceola, Mississippi. Tate won by a second round technical knockout (TKO).

From there, they went on to win multiple tournaments throughout the southeast. Tate even took second at the 1975 National Golden Gloves Tournament in Knoxville.

It was after one of these bouts that Tate changed the course of his career when he asked an opponent how he learned how to box so well. The fighter pointed to trainer Jerry “Ace” Miller.

“John Tate, I saw him fight in the Southeastern USA Boxing Tournament and he beat a heavyweight that nobody could beat, a guy named Jimmy Stancil from Chattanooga, and he stopped him," Ace said in a later interview. "He came over to me and he said, ‘What did you think about that fight, Mr. Miller?’ I said, ‘Well, that’s the second time I’ve seen you fight, son. The first time you got knocked out, that time you knocked the guy out.’ I said, ‘If you come to Knoxville and listen to what you’re told to do, you’ll be champion of the world.’ He said, ‘I’m coming. I’m coming.'"

Tate kept his word and hopped a Greyhound to Knoxville. Stepping off the bus, the first person he called was Ace.

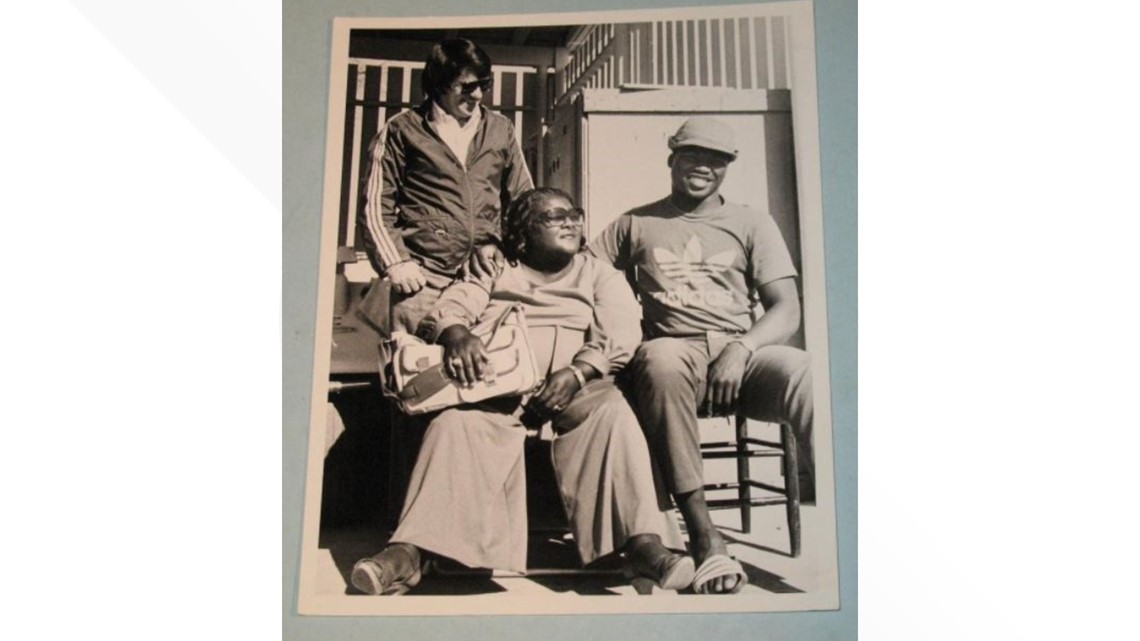

Upon his arrival, Miller welcomed John as a member of his own family.

“It was as if he was a brother really to me. He looked to my mom and dad as his parents sometimes. He spent so much time with us, and we were around him so much that I think he just became part of that family,” said Tracy Miller-Davis, Ace’s daughter.

Ace offered his new fighter a bedroom at the pool hall turned boxing gym, Golden Gloves, in East Knoxville where he would be training.

“Daddy would come here and stay with him to watch him because John was not always the perfect candidate. He’d drift off and find the nearest rib place or McDonald’s, wherever he could go to find a meal,” Tracy said. “They even had a camper parked out in the back of the gym and they would sleep in that camper just because he wanted to keep an eye on him to keep his weight down and to keep the ladies away.”

The Golden Gloves gym is also where Tate found a loyal crew that he dubbed “The Hillbillies” with nicknames like Mouse, Tank, Bad Eye, Mad Dog and Wrong Way.

“A bunch of good ole boys. We’re just electricians, telephone men, just friends. It was a team. Everybody had something to do. You have one person that sets up the stool, one person cools him off and only one person giving instructions. Either I was on the stool or I was giving him water, cooling him off. Ace was in the ring giving instructions,” said Judge Hill, Tate’s former cornerman.

Team Tate was now complete, but what looked like a perfect match for some had a rocky start.

“He was trying to box and couldn’t box. I would go out to the gym and watch him spar some people, and he started to grow and get bigger. He still couldn’t fight. Even the little guys were beating up on him,” said Thomas “Tank” Strickland, a former boxing promoter and Tate's friend. “I’ve seen it time and time again in boxing. A man will get tired of taking a whipping and it’s time for him to start whipping, and just overnight, John got tired, I presume, and then he started whipping people.”

Tate was just getting started.

“Everybody laughed at us. They said he was big, dumb and slow. No one wanted us anywhere. Then one night, we were invited to St. Louis where Big John knocked out the Polish champion,” Ace said.

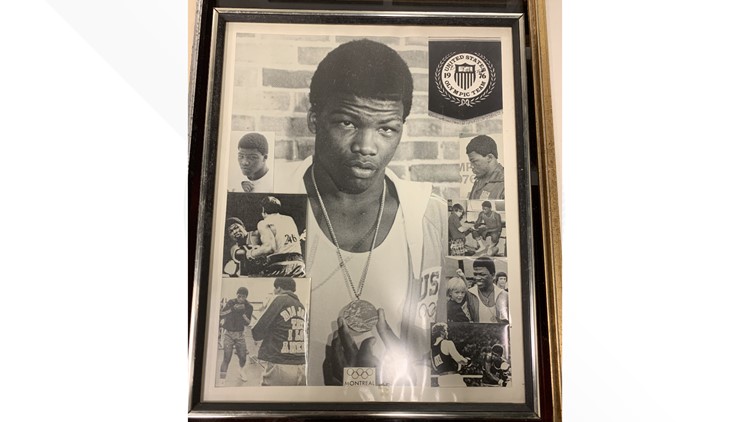

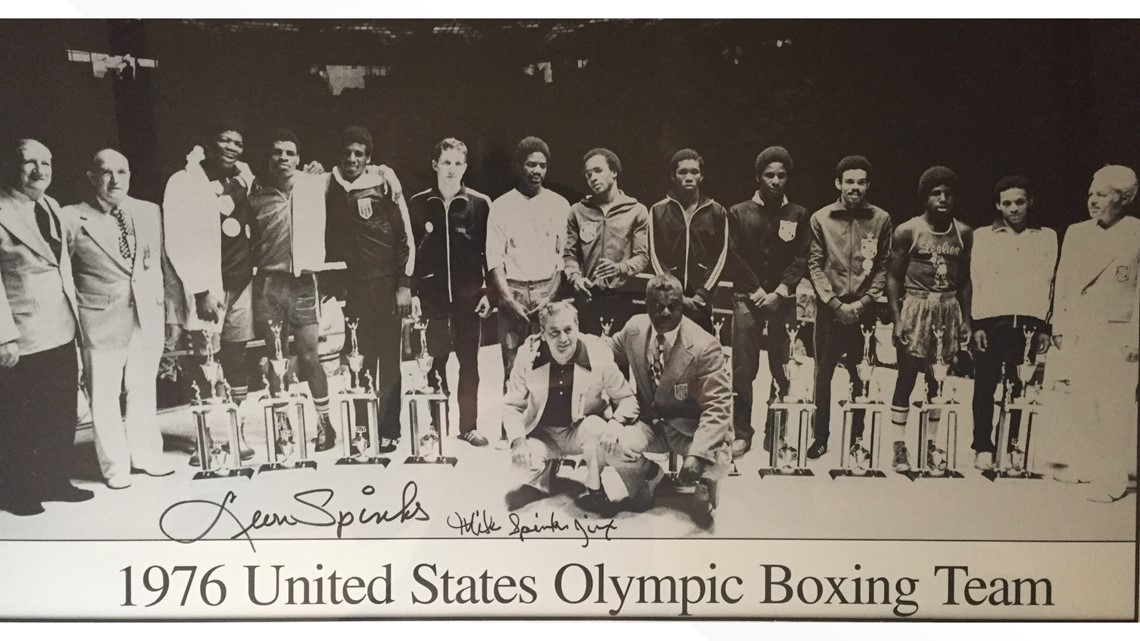

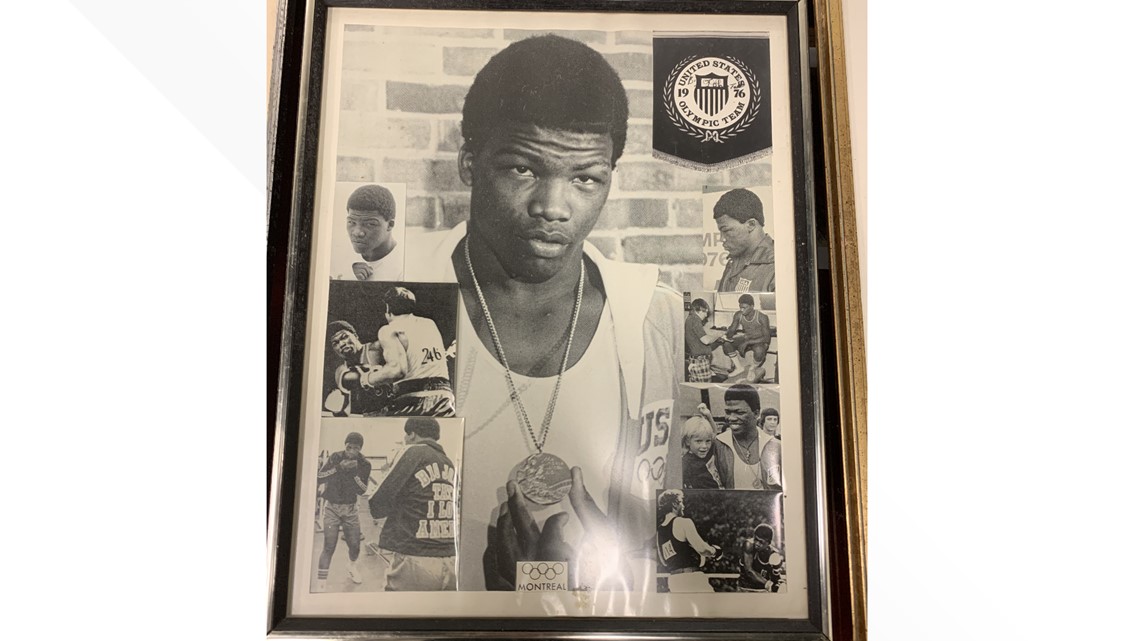

Ace and Tate persevered and made it to the Olympic trials for the 1976 Montreal games. Arriving at the event, the pair could be overheard singing the ditty, “Every day at the gym you can see him arise. He stands 6’4 and weighs 225.”

To make the team, however, Tate would have to fight and beat two opponents whom he had lost to earlier in the year: Michael Dokes and Marvin Stinson, which he did and punched his ticket to the 1976 summer games.

He was joined by teammates and future world champions Michael and Leon Spinks and Sugar Ray Leonard.

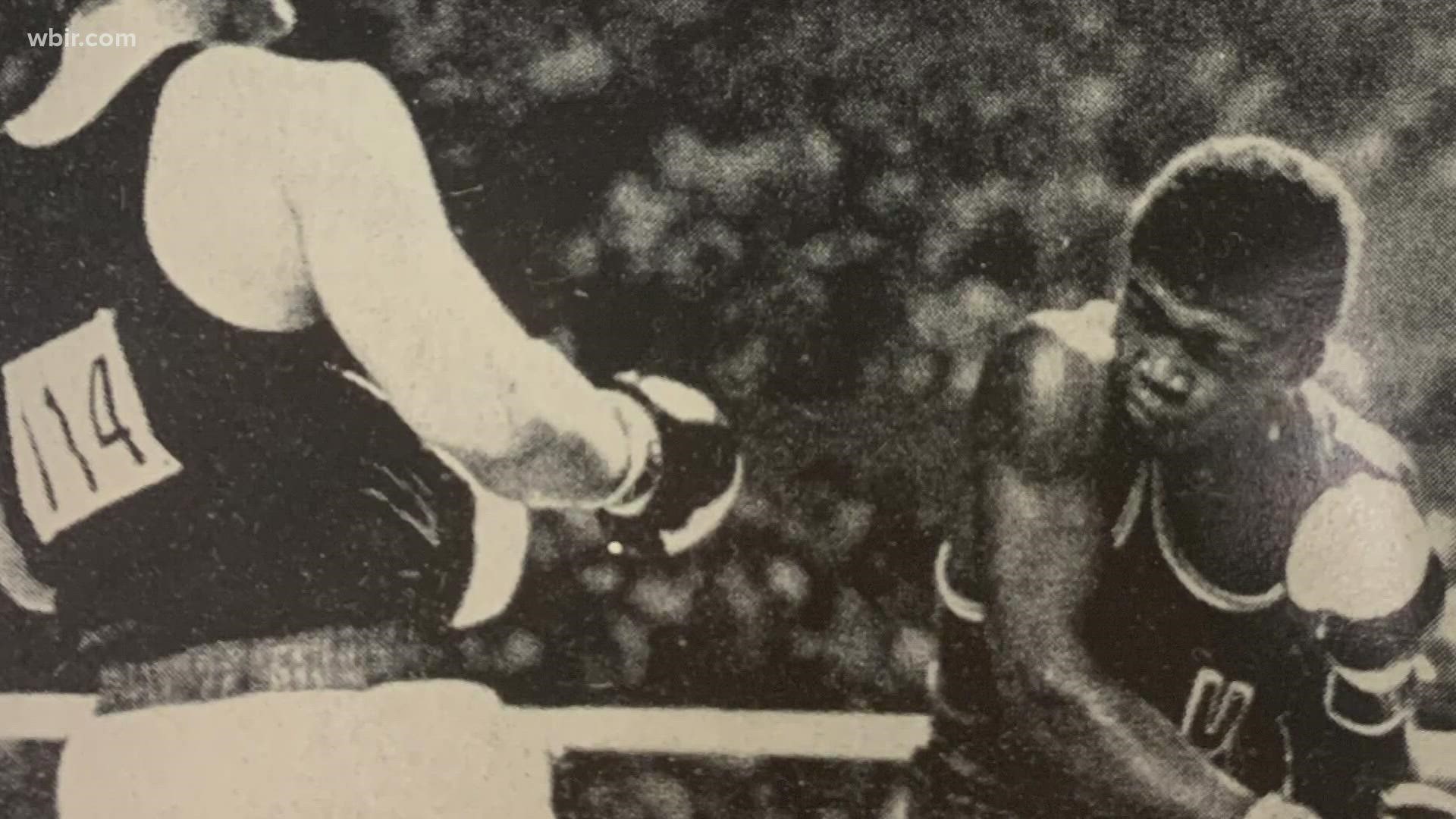

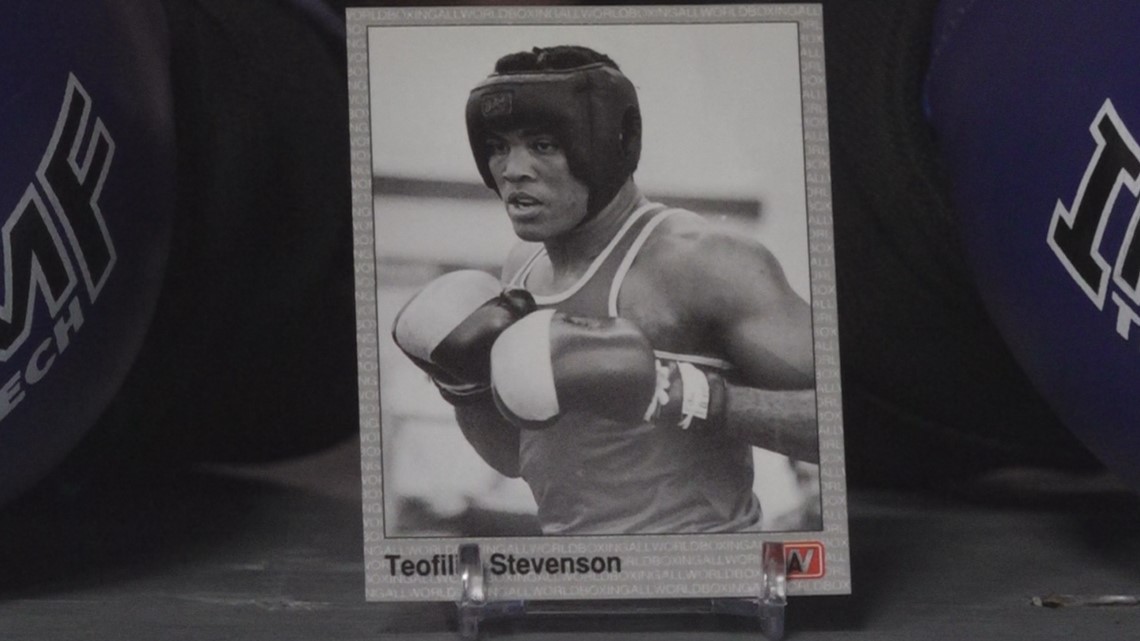

In Montreal, things seemed to be going well for Tate. He dispatched his first two opponents and found himself in the semifinals against reigning Olympic Champion Teofilo Stevenson from Cuba.

Despite suffering a severe cut above his left eye and the team’s manager advising him to pull out of his next bout, Big John pressed forward.

“I knew when I got in the game, my coach, Ace Miller, told me, ‘If you’re gonna be good, John, you gotta put in the cost,’ and I put in the cost to be the boss of the heavyweight division in the United States. I knew one day I would have to represent my country in the Olympics and now I’m here,” Tate told reporters before the bout.

“Big John Tate, the 21-year-old truck driver from Knoxville, Tennessee, now inside the ring awaiting the start of action. Look at that left eye. It looks hideous.”

During his pre-fight interview, Stevenson vowed to stick to his own style of boxing and not focus on Tate’s cut.

The cut, however, was a non-factor in the fight's outcome.

“If anyone knows anything about Stevenson, Stevenson was a grown man. He won about five Olympics so he was about 40 years old at the time fighting those young kids,” Tank said.

With a single right hand from Stevenson, Tate’s dream of Olympic gold was shattered with 1:31 left in the first round.

“Tate is a tremendous individual too. Can’t take anything away from him,” champion boxer and fight commentator George Foreman said at the end of the bout.

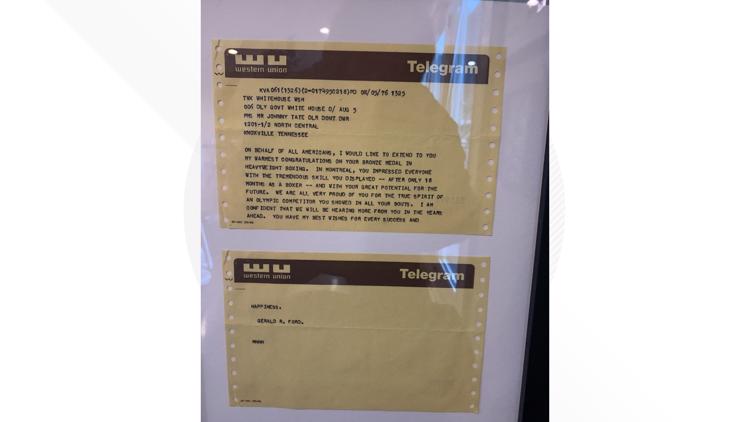

Even in defeat, Tate was still able to secure a bronze medal for his country in the 21st Olympiad, even garnering recognition from then U.S. President Gerald R. Ford. He returned to Knoxville and began his professional career.

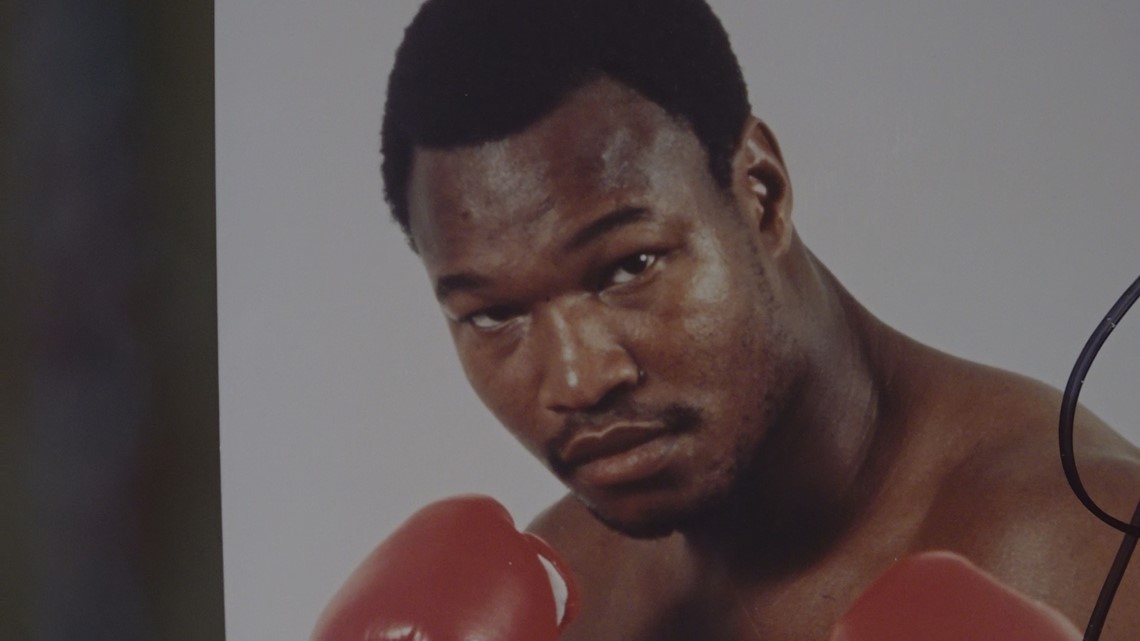

Big John's Rise

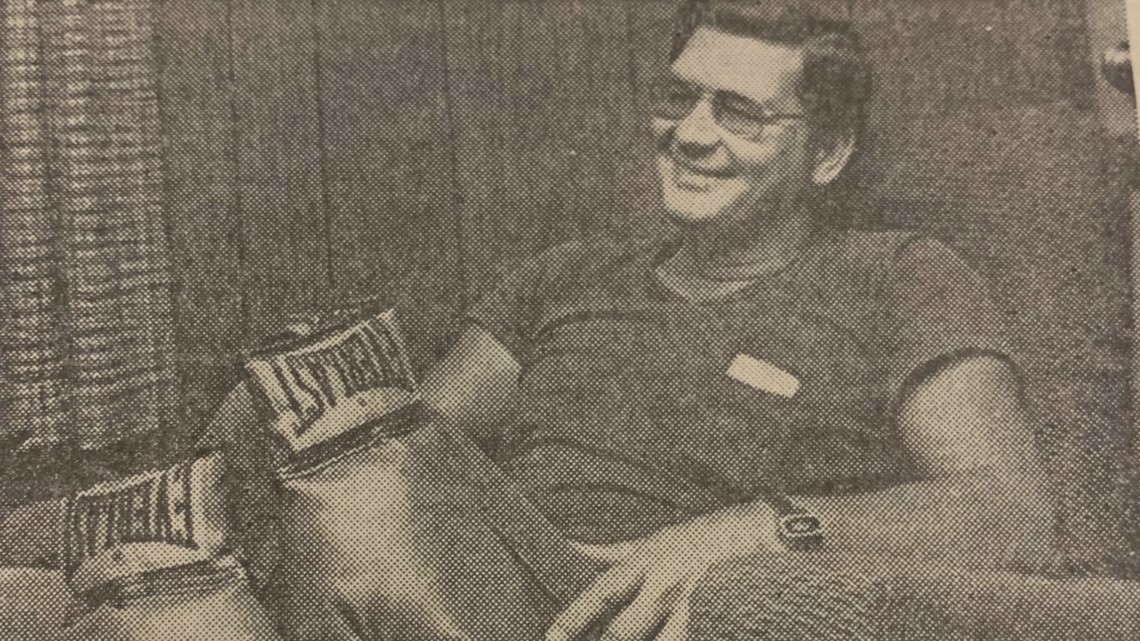

In March 1977, John Tate signed to Bob Arum’s Top Rank Promotions. Still unable to write, Tate signed his name on the contract with an X.

By May, Tate was making his professional debut, winning his initial outing with a fifth round TKO over Jerry Thompkins.

“He was a big guy. That’s for sure. He was easy-going, easy to communicate with, coachable. He put the time in. You’d sit there and work with him for hours and hours and hours, and he would work just as long as you would,” Judge said. “He wasn’t a fast boxer. He wasn’t a one-punch knockout fighter. He was the kind of guy that you don’t get tired on because he was still going to be there. He plodded, he put his punches together and he worked.”

Watch a 1977 Big John Tate fight in Knoxville:

Over the next two years, Tate would step into the ring 16 more times, compiling a record of 17 wins and no losses, with 14 of his wins by knockout.

“His early career was like any boxer’s early career. You start out with weaker opponents because you’re trying to gain the knowledge of boxing and the different styles. Then you start upgrading your competition. You’ll do that for the first 15 fights at least. Now it’s time to move on up,” Tank said.

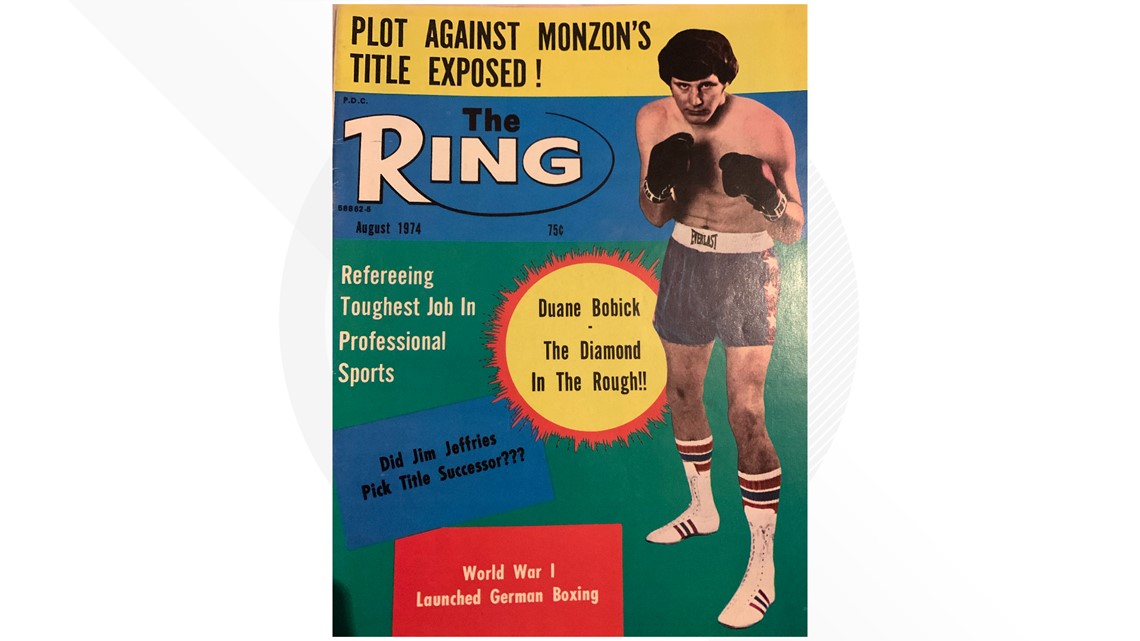

His first big test came in January 1979 against former National Golden Gloves Champion Duane Bobick. Like Tate, he too lost to Teofilo Stevenson with a TKO in the 1972 Olympics, but Bobick boasted an impressive 48-2 record with 42 of his wins coming by knockout.

Just over two minutes into the fight, Bobick had been down already and was catching punches from Big John.

“They hand-feed you matches, matches that you’re supposed to win, and they build this great big old record up there and the guy can’t fight. John took him to school that night. We knew John could fight, and he took care of business,” Judge said.

Just like that, at only 23 years old, Tate found himself in the race for a shot at the heavyweight title.

“What a win for John Tate. You’ll see a smile that closely resembles that of Muhammad Ali.”

In September 1978, Muhammad Ali won the heavyweight championship for a record third time. Retiring soon thereafter, his title was left vacant.

Four top-ranked fighters were chosen to be the heir apparent to Ali’s throne: two South Africans, Kallie Knoetze and Gerrie Coetzee, and two Americans, Leon Spinks and Big John Tate.

The quartet of pugilists would face off against one another in a three-fight tournament of sorts with the winner receiving the World Boxing Association (WBA) World Heavyweight Championship.

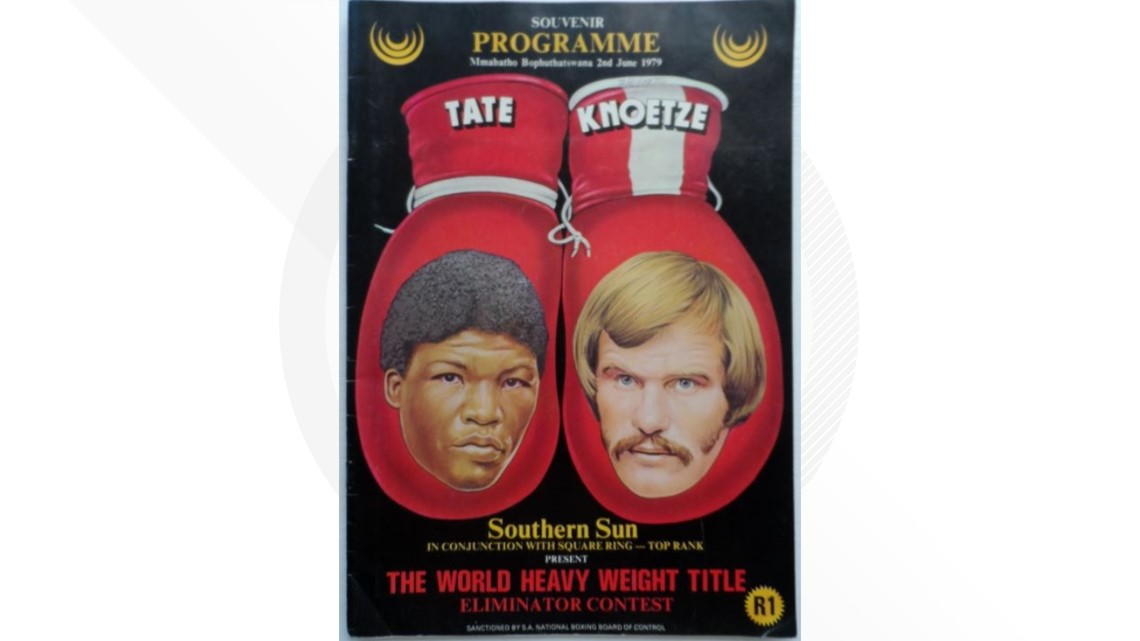

For the first fight, John Tate would travel over 8,000 miles to take on Kallie Knoetze in Mmabatho, Bophuthatswana, South Africa, a country torn apart by the racial segregation of apartheid. The bout was set for the 40,000-seat Independence Soccer Stadium.

“I was excited about going, but at that time, I didn’t know what I was getting into. It’s a long flight and we get off the plane and they had armed security guards and attack dogs, German Shepherds, that escorted you from the plane to the airport. It was a different world altogether for me,” Judge said.

Knoetze’s past also served as fuel for the fight.

“He had been a white policeman, and I believe he was involved in the shooting of a Black youth. The Blacks in South Africa loved Big John. So this was a white policeman fighting a Black athlete from America, and it was a big deal,” said William Kouns, a former amateur boxer who trained with Tate.

Despite the racial tensions of that time, a New York Times writer referred to Tate as an “honorary white” exempt from the restrictions of apartheid. John was welcomed with open arms by both Black and white people in South Africa. He even acted as a spokesperson for watches, clothing and a brand of corn-fed chicken.

Before the fight, Knoetze took shots at Tate in the local papers by calling him “baby fat” and saying John would have to be Superman to beat him. The white fighter was quick to insist the verbal jabs weren’t motivated by race.

“I don’t see Tate as Black. I see him only as a man I have to fight, and when it’s all over, I’ll shake his hand,” Knoetze said at the time.

By fight time, the stadium packed in 51,000 spectators to witness the contest.

“They escorted you to the ring with dogs. We are in a big ole soccer stadium and we are in the middle of it, and people were climbing up the bleachers, falling off,” Judge said.

At the time, Tate vs.Knoetze became the highest-grossing nontitle fight in boxing history with an impressive $750,000 gate.

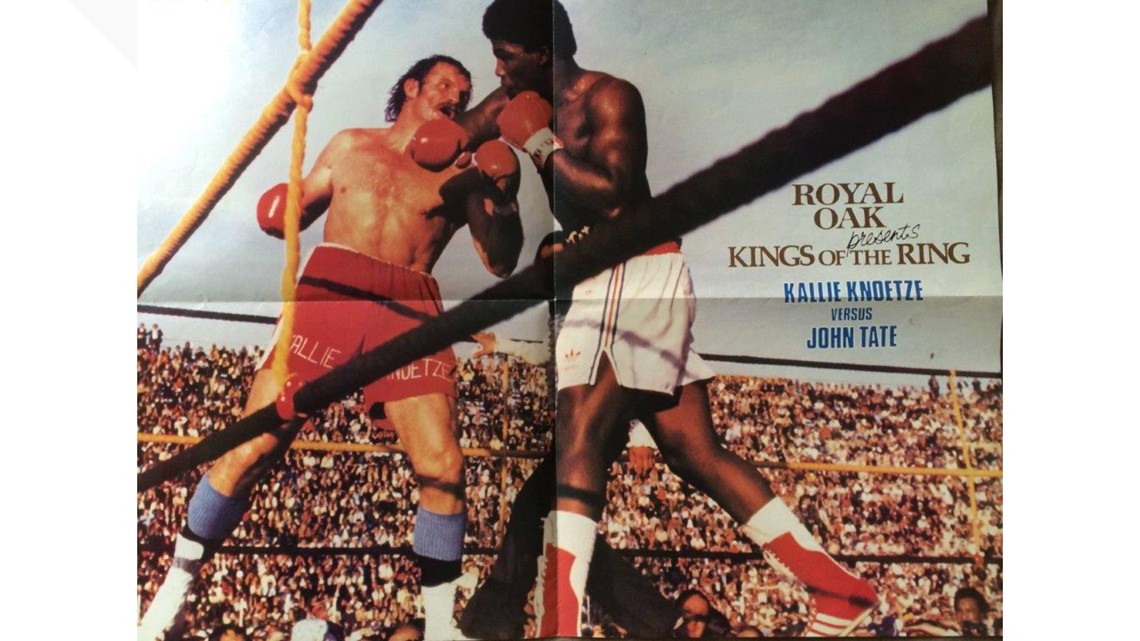

The first two rounds were relatively quiet for Tate, who employed a stick and move strategy. In the third, however, Knoetze scored a right hand on John.

“When John got his balance back and got to the center of the ring, he asked him, he said, ‘Are you through, boy?’ That’s when John went to work,” said Ray Ingram, one of Tate’s Hillbillies, at the time.

From the fourth round on, it was all Big John.

“When John started beating on him, you could hear a pin drop in that ring. That’s how quiet it got,” Judge said.

In the eighth, the accumulated damage was too much for Knoetze, as he began stumbling around the ring.

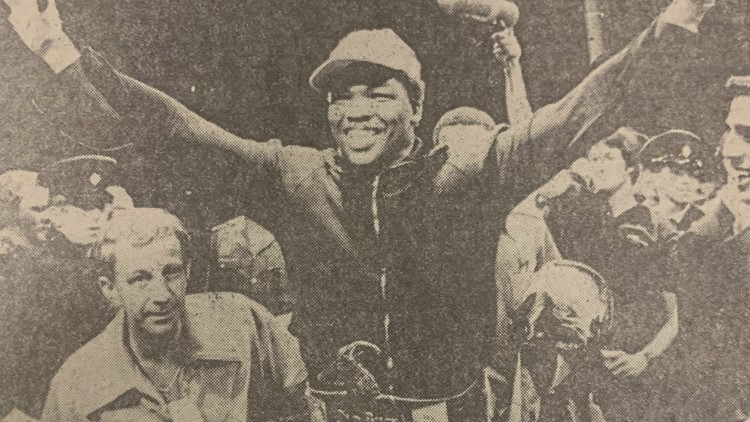

“Referee Rodriguez has no choice but to stop it! It’s all over!”

It was an eighth round TKO for Big John Tate, and with it, an opportunity to fight for the Heavyweight Championship of the World.

Knoetze made good on his pre-fight statements and went to Big John’s corner to shake his hand.

“When we got John to the dressing room, [Knoetze] came back there through the police and all that stuff, he came in and sat down and him and John drank Gatorade, and he told John, ‘You’re terrific.’ He told Ace, ‘It’s the body shots.' He said, 'Nobody hits like this heavyweight you got,’” Ingram said in an interview.

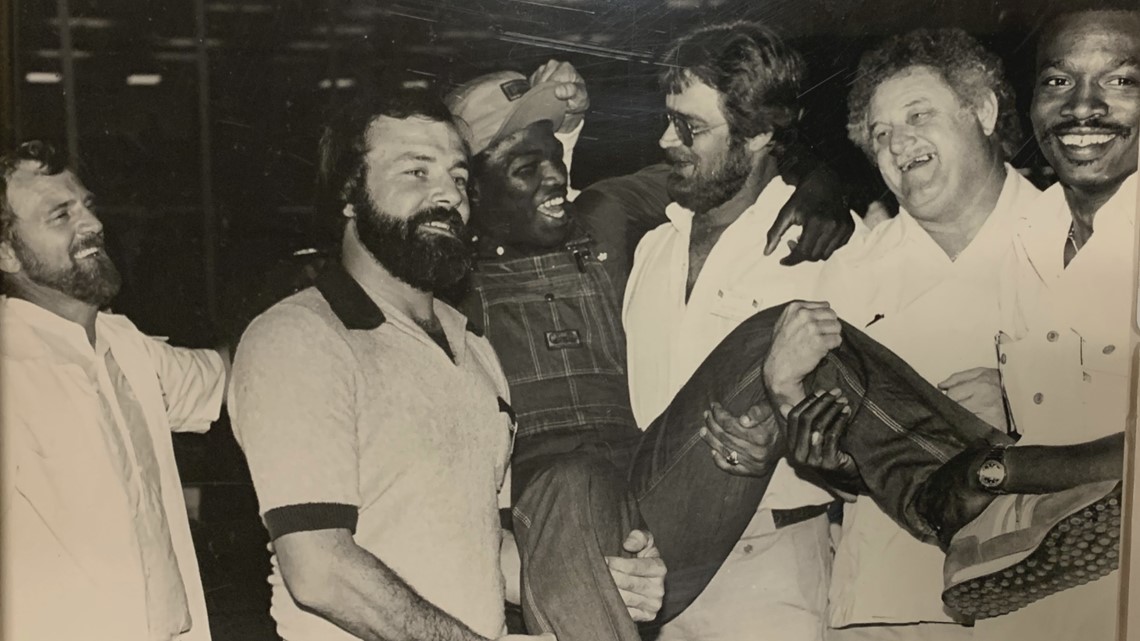

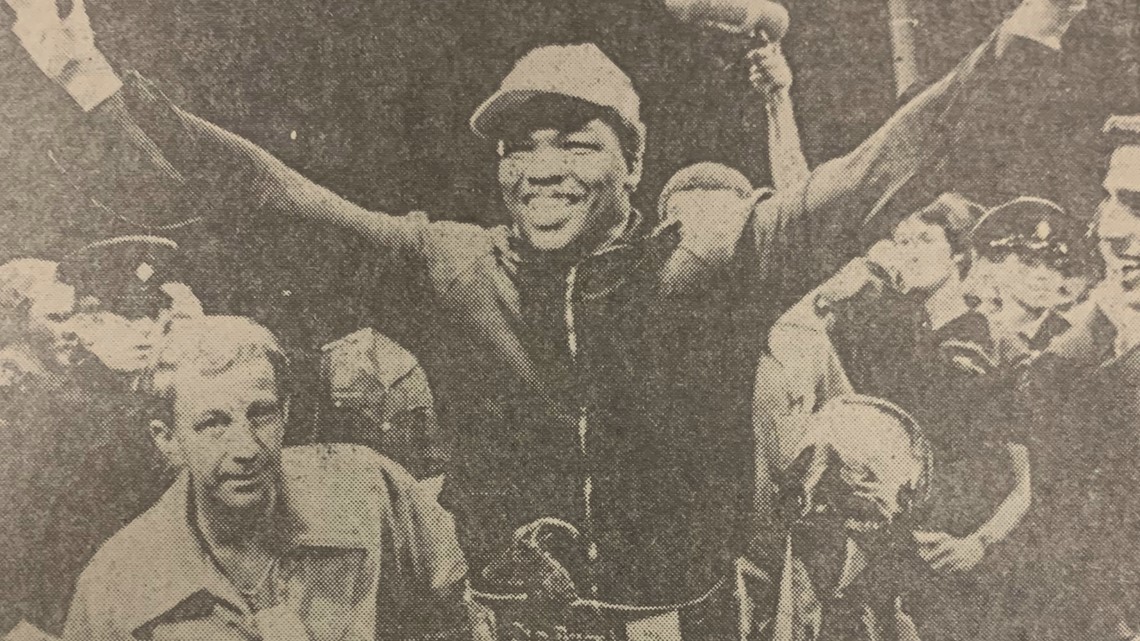

Along with the victory, Tate took home $350,000. Soon after, John and his merry group of Hillbillies landed in Knoxville to a hero’s welcome.

People lined the streets just to get a glimpse of the hometown boy on the verge of a championship parading through the streets in a convertible.

“It was a big, fun time in Knoxville, Tennessee. Everybody knew who Big John was. Everyone was behind Big John. Everywhere he went it was just, ‘Big John, come on in!’ Everybody was behind him, the whole city of Knoxville,” Tank said.

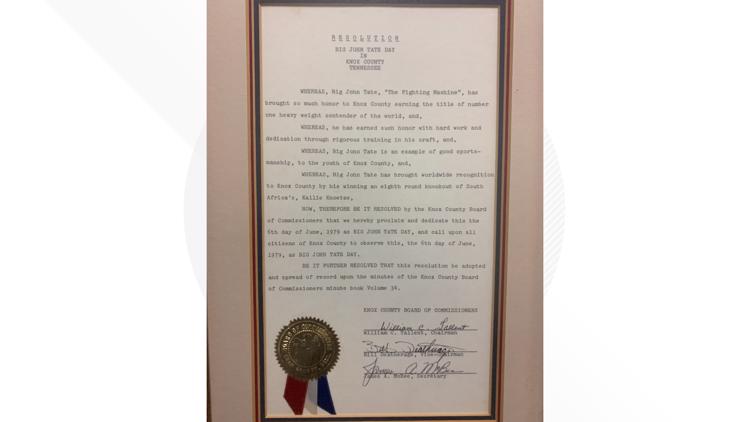

Randy Tyree, then mayor of Knoxville, proclaimed June 6, 1979, as Big John Tate Day.

“We’ve had a lot of famous people here, and, of course, Big John was one of the biggest. He was perhaps the biggest thing to happen to Knoxville other than when the World’s Fair came in 1982,” Knoxville historian Robert Booker said.

Watch WBIR's coverage of Big John's victory celebration in Knoxville:

Never at a loss for words, Ace Miller vowed to bring the championship home to K-Town.

“They love us in Knoxville, Tennessee. You love Knoxville, Tennessee. We’ll continue to put Knoxville, Tennessee on the map. As long as we can stay up there and fight, John Tate is going to be the next World Heavyweight Champion,” Ace said at the time.

One fight away from the crown, Ace and Tate flew to Monaco for the match between Gerrie Coetzee and Leon Spinks. The victor would face Big John.

World Heavyweight Championship

In only his eighth professional fight, Leon Spinks won the heavyweight championship after 15 rounds with Muhammad Ali.

In his ninth professional contest, after 15 more rounds with “The Greatest,” Spinks lost a unanimous decision and his title.

In his 10th professional fight, the man who fought Muhammad Ali for 30 rounds, 90 minutes total, was knocked out in a mere 2:03 by Gerrie Coetzee in Monaco.

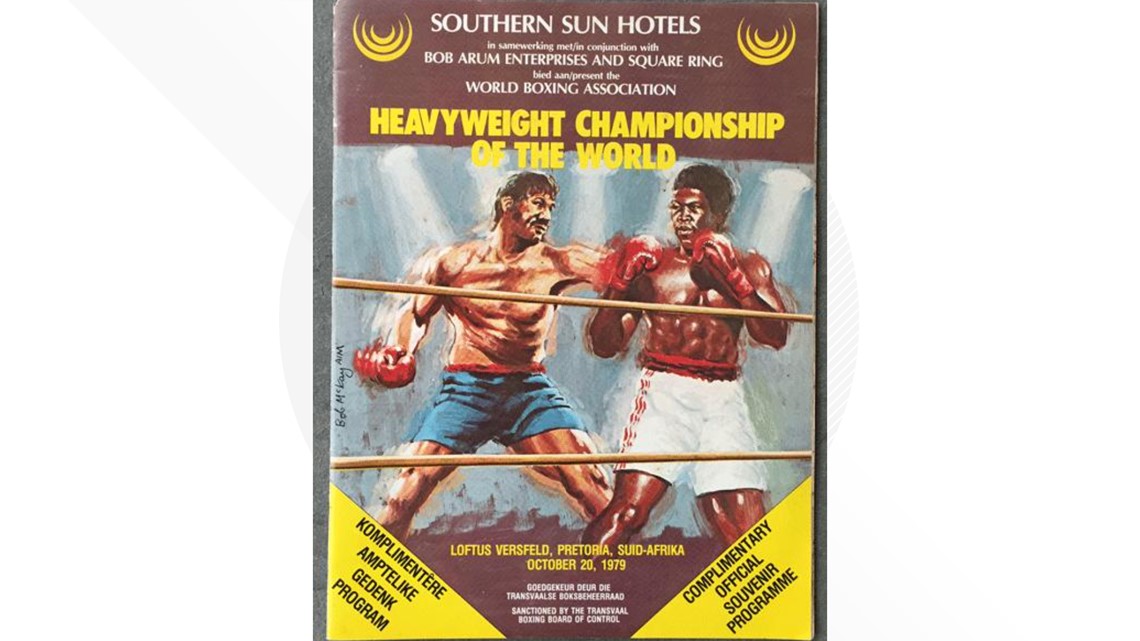

The WBA Heavyweight Championship fight would be between Big John Tate and Gerrie Coetzee.

The bout was set for Pretoria, South Africa at the Loftus Versfeld Stadium, a venue primarily used to stage rugby matches and exclusively whites only. That fact provoked the ire of civil rights leader Jesse Jackson who called for boycotts of the fight and said John Tate would be a traitor to his race if he fought in that arena.

Despite the criticism, Tate arrived in South Africa 11 weeks before the fight with Coetzee.

“I have to go where the championship is at. If the championship were in New York or Madison Square Garden or anywhere like that, I’d be fighting there, but it ain’t there. It’s here in South Africa,” Tate said at the time. “I think God would like for me to fight for the title here and to win to change some of the things in South Africa for the peoples.”

Kouns said Coetzee, himself, had spoken out against apartheid.

Although both fighters tried to avoid politics in the pre-fight build-up, promoter Bob Arum voiced opposition to the separatist political ideology of apartheid.

“I think it’s an abomination, and I think most decent people feel the same way,” Arum said at the time.

After Arum’s many meetings with government leaders came a surprise decision. For the first time in history, Loftus Versfeld Stadium would be desegregated and welcome both whites and Blacks for the fight John Tate had dubbed “The Story in Pretoria.”

“Forty miles outside of Johannesburg, and this is the most significant sports event South Africa has ever seen.”

On Oct. 20, 1979, over 80,000 people, roughly 5% of them Black, packed the rugby stadium turned boxing arena. Tate vs. Coetzee marked the largest crowd to witness a boxing match in more than 50 years.

Tate wore white. Coetzee wore blue.

The bout started off slow with neither fighter gaining an advantage until late in the third round. A one-two from Coetzee staggered Tate, but he managed to hang on for the remaining seconds of the round.

Then, early in the fourth round, a left-hand wobbled Tate, his glove nearly grazing the canvas. The Knoxville fighter managed to regain his composure, and by the 11th round, he gained control of the fight.

“Gerrie could punch. He had a big right hand on him. John just outboxed him, just took him to school,” Judge said.

Coetzee stood his ground to the final bell, and the two fighters embraced, awaiting the judge’s decision.

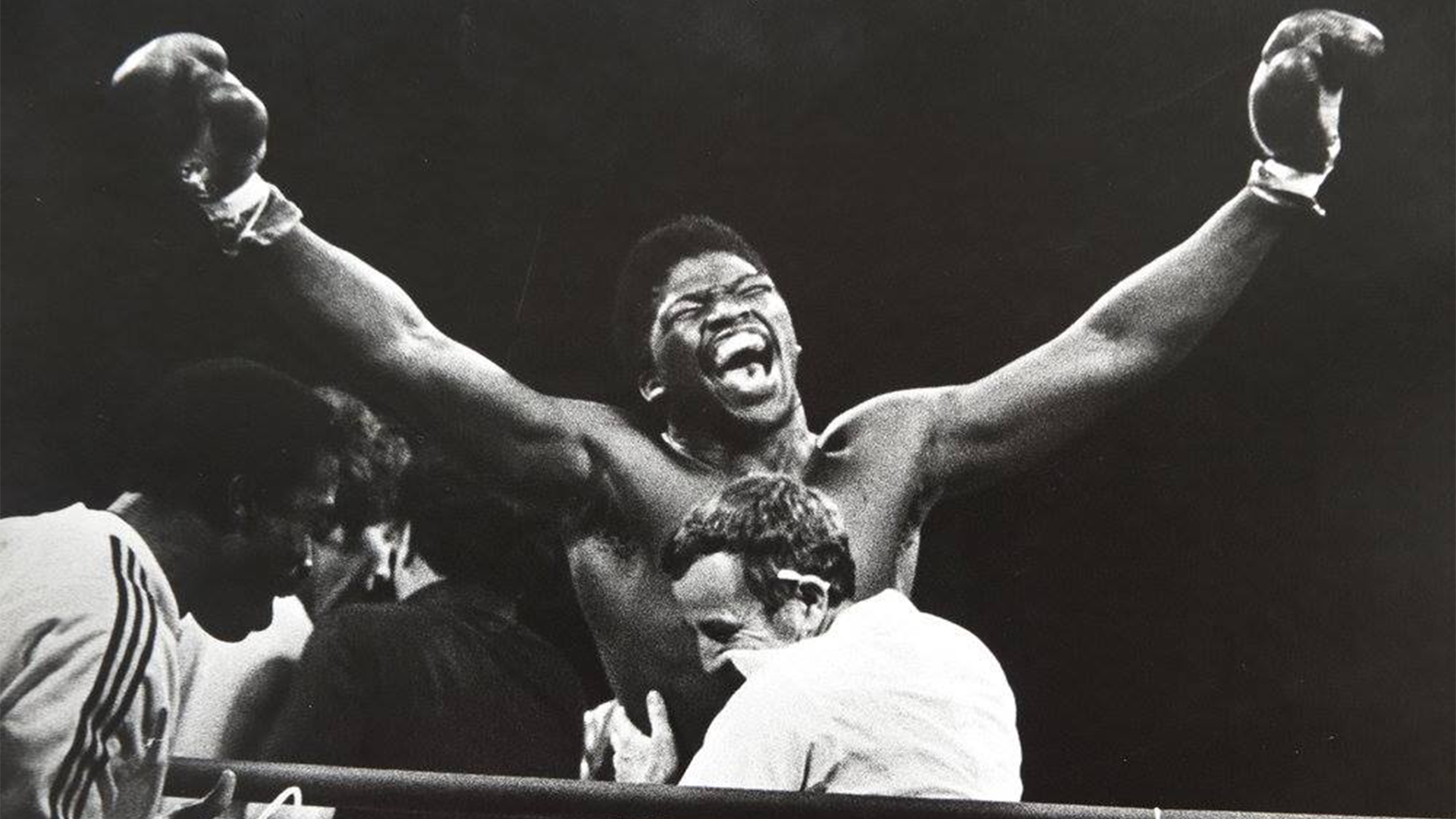

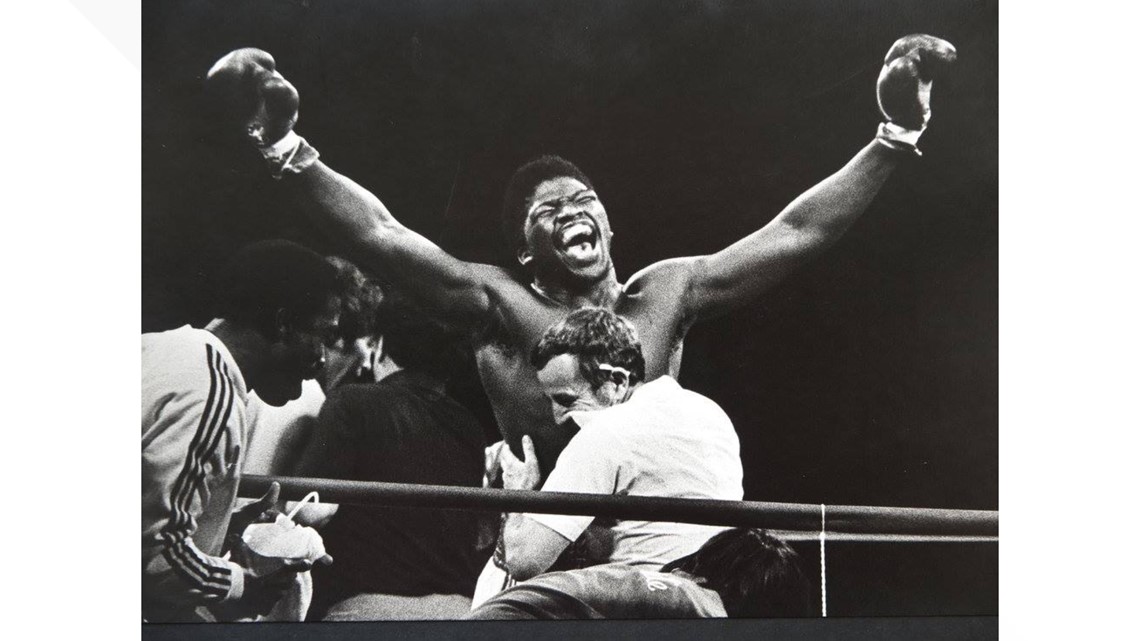

“The new Heavyweight Champion of the World, John Tate!”

“It was really something. He just destroyed Coetzee with boxing. Instead of slugging it out with him, he stayed to the fight plan all the way through, just out-maneuvered him and won the fight,” Ace said in a later interview.

Adorned with his $27,000 gold championship belt, awarded by Old Buck Brewery of South Africa, Big John Tate returned to Knoxville as a world champion.

Learn more about the history of the Old Buck Belt:

“He told me one time that being Heavyweight Champion of the World is like being President of the United States. I said, ‘That’s a pretty good statement, John, because you are an ambassador for your country. You’re an ambassador for this town right here in Knoxville, Tennessee,’” Ace said.

Booker said Big John’s win was a boon for the Scruffy City.

“I really think it helped the image of Knoxville that you could have this poor, uneducated fellow who came to town riding on the back of a trash truck who would eventually become Heavyweight Champion of the World,” Booker said.

Heavy is the head that wears the crown, and soon after winning the championship, title defense talks began.

One possible matchup was a unification bout with World Boxing Council (WBC) Champion Larry Holmes, who most observers felt was the “true” heavyweight champion.

The other, more likely option for Tate was a bout with Muhammad Ali tentatively set for June 27, 1980, in Taipei, Taiwan. The fight with Ali would net both fighters their share of $14 million, making it the “greatest amount to ever be paid to two fighters in the history of boxing,” with Tate seeing over $3 million of the prize money.

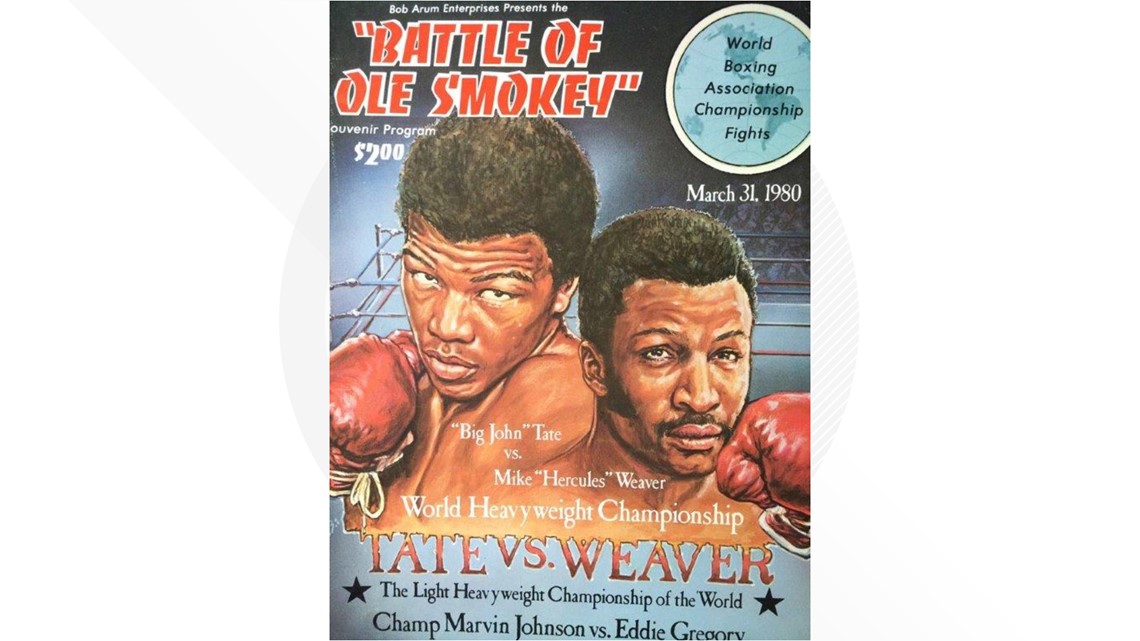

First, standing in John Tate’s way of either title unification or riches, was the 20-9 journeyman, Mike “Hercules” Weaver.

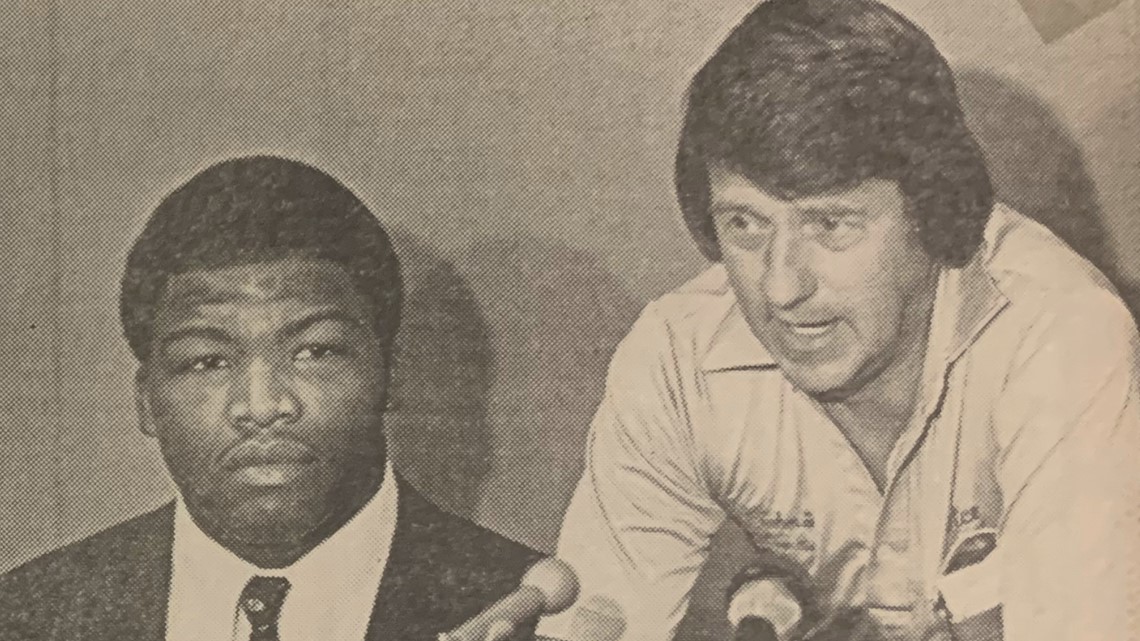

“The Battle of Ole Smokey will consist of many great fights. It’s an event which will make a great impact all over the world,” Arum said before the fight.

The Heavyweight Championship of the World came to Knoxville and would be defended at Stokely Athletic Center on the University of Tennessee campus. At the pre-fight press conference, Weaver was reserved.

“I’ll have to say it’ll be a good fight. Tate’s a very good fighter and a very good champion. I’m also a very good contender so I’m out here to do my best, do a good show. Thank you very much,” Weaver said at the time.

Champion John Tate, sporting his trademark cowboy hat and taking bites out of a big orange, was all smiles.

“I can assure you of one thing. The people who buy a ticket to this fight here, you won’t be disappointed because I worked too hard to get this title I got, the WBA, and I ain’t about to lose it yet because I’ve spent too many hours, too many days. People say, ‘Oh, he can’t fight. He can’t do this. He’s just a big baby.’ and all this. I just don’t see how you win, Mike. Thank you very much,” Tate said.

Ace encouraged East Tennessee to turn out and “sell it like a championship fight.”

“This is a great fight card and a great fight for our city, for our state, for this whole end of the country. We’re very fortunate to have Mike Weaver and his manager come this far for this fight, come into the lion’s den as they may say,” Ace said. “Of course, he’s a tough guy, so he’s gonna be in there throwing his lines and his punches and claws.”

Watch the 1980 pre-fight press conference with Tate and Weaver:

A title defense against Muhammad Ali seemed to be on the horizon, but it was the furthest thing from Big John's mind.

“Until I can defeat Mike Weaver, I ain’t gonna think about no Ali. If I don’t beat him, it’ll be Mike Weaver fighting him. So, until I can beat Mike Weaver, I won’t even attempt to think about fighting Ali or anyone else as far as that goes,” Tate said.

The almost 13,000 on hand in Stokely on the night of the fight were firmly behind their hometown hero with cheers of “BIG JOHN TATE!” pulsing through the athletic center.

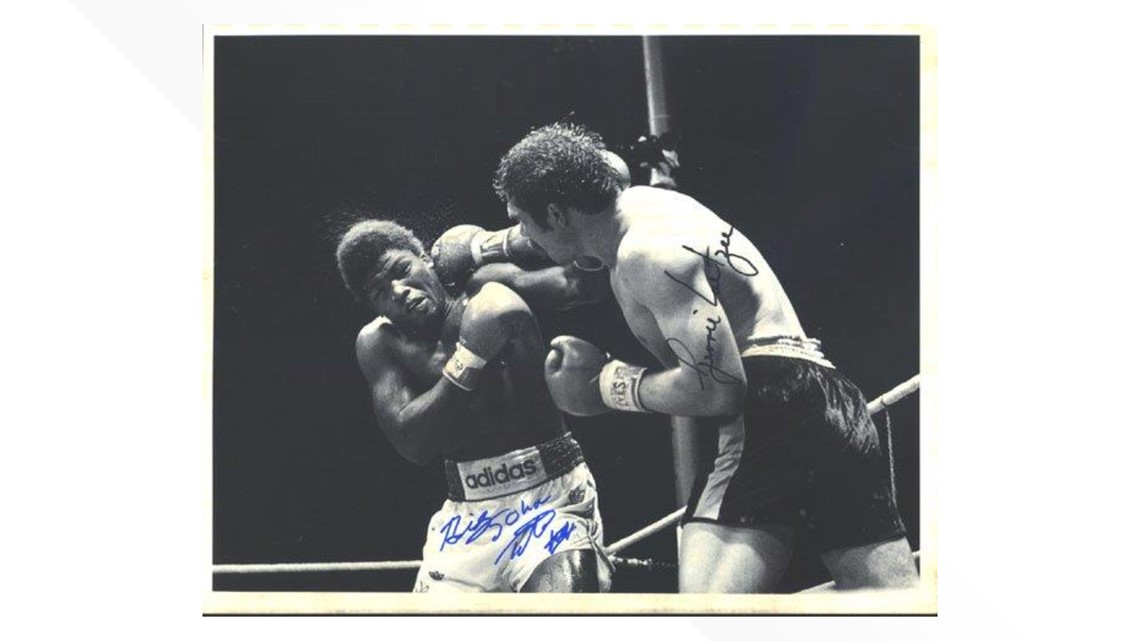

What seemed like a mismatch on paper was proving to be just that as Big John cruised ahead on the judge’s scorecards.

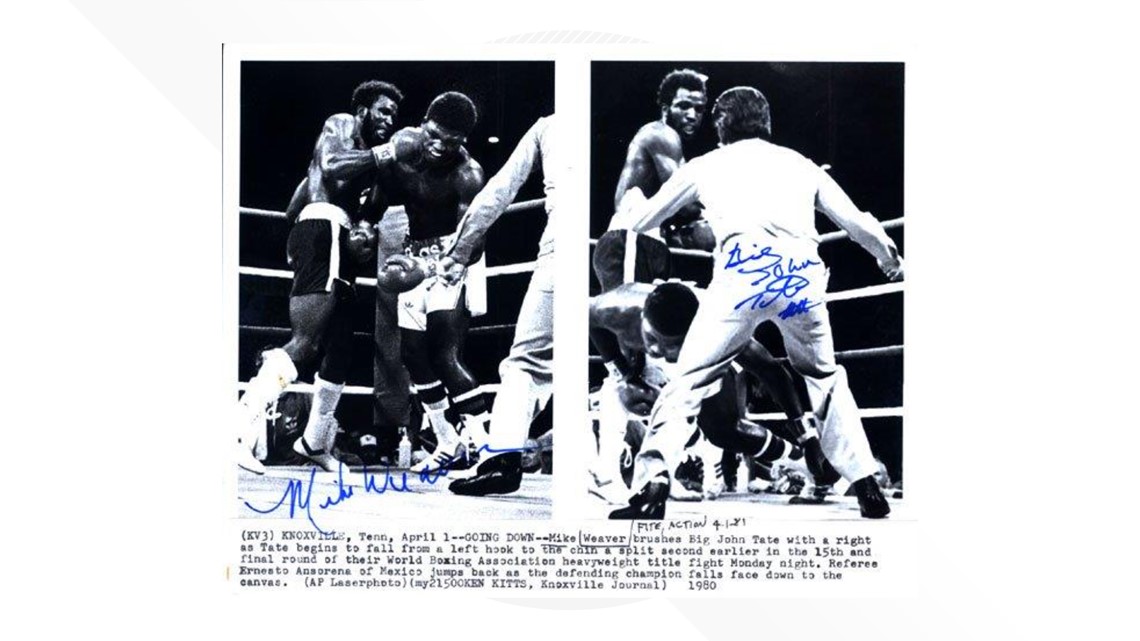

Late in the fight, however, Weaver landed a left hook.

“I’m looking at John and I’m saying, ‘My gosh! I think we’ve got a broken jaw!’ He got hit and blood came right out of his mouth. It was a hard shot, and he didn’t know where he was," Judge said. "From that point on, he was just responding to what went on in the corner. We would tell him to jab, and he would do it. He just wasn’t doing it on his own. We got him just about through it.”

By the final round, chants of “BIG JOHN TATE!” still echoed around Stokely.

“He was told if Weaver comes in, hug him, dance with him the whole round, stay away from him. But then you’ve got the background. 15,000-17,000 people in Stokely, ‘Big John! Big John! Big John!’ Well, you hear that and it was piping him up, so John wanted to go out, and he had forgotten everything that was said and he wants to go out and show his superiority in front of all of his Knoxville fans,” Tank said.

As the bell sounded, the commentators had all but written Mike Weaver off.

“I know the spirit’s willing. I’m not sure of the body,” they said as round 15 began.

John Tate was three minutes away from retaining his title. Three minutes from a potential fight with Muhammad Ali. Three minutes from glory.

With only 45 seconds remaining…

“Weaver hit him with a left!”

“8, 9, you’re out!”

Tate lay motionless in the ring as Mike Weaver stood over him, the new Heavyweight Champion of the World. Big John’s reign was over in a now silent Stokely.

“I was the person that counted John out. At that point, I was working as the timekeeper. When he fell, he fell looking at me. I’m thinking, ‘Get up John!’ but his eyes were open and he was just out," Tank said. "I went back to the dressing room after the fight myself. He asked me, ‘Did I lose my fight?’ ‘Yeah, John, you lost.’ He didn’t even know it."

Kouns said the following weeks were not kind to Big John.

“It was like, ‘Oh it was a lucky win before for him when he won the title,’" Kouns said. "Now everyone writes off your accomplishment, even though you’ve reached this pinnacle of athleticism, and it was sad."

His heart breaking for his surrogate son, Ace vowed they would reclaim the title.

Big John's Battles

81 days after his loss to Weaver, Tate was fighting on the undercard of the Sugar Ray Leonard vs. Roberto Duran megafight in Montreal.

His opponent for the scheduled 10-round bout: Trevor Berbick from Jamaica.

Some were ready to see Big John get back in the ring.

“It’s like falling off a horse. You get back on and get that little fear out of you. In this ring right here, if you get caught, and get caught really solid, it takes a while to get over it,” Judge said.

Others worried it was too soon.

“I think that was too big of a fight to come back with. He should’ve fought a lesser opponent at the time. I think after a devastating loss of your world title, I think you just need a little bit more rest,” Tank said.

The early rounds were competitive, but as the fight drew on, it became apparent Berbick was too much for Big John.

At the start of the ninth stanza, Berbick landed a combination that sent Big John stumbling across the ring and onto the canvas.

In a scene reminiscent of his fight with Mike Weaver, John Tate was face down as the referee counted. His body eerily twitched as Ace Miller rushed to his fighter’s aid.

“I wasn’t scared when Mike Weaver knocked John out in March, but when somebody like Trevor Berbick hits John twice in the back of the head, that scared me a lot,” Ace said.

After his defeat, John would take a doctor-mandated six-month sabbatical from the ring.

“He was a different person altogether because he had been knocked out by two different people. The confidence was gone. It was gone,” Judge said.

He spent his downtime focused on his other hobbies like hunting, fishing, hiking, camping and tending to his beloved dogs.

Tank recalled a time Big John shot a boar with a bow and arrow, cooked it and served it. When Tank asked where the meat came from, Tate pointed to a mounted boar head on the wall.

“John liked that cowboy image. He liked to have the big Stetson hat. He wanted to be larger than life, but he was still like a kid," Tracy said. "We went to Hawaii when I was 13 for the National Golden Gloves, and he went with us and would not get near the beach because he just watched Jaws. He was very kid-like. He just was, but that made him very humble and very kind."

In the fall of 1980, John married Claudia Bradley, a buyer for a national clothing chain. The pair connected two years prior in the summer of 1978.

“I had been transferred here from San Francisco. I just went to get a free record. I didn’t know who John Tate was. We talked a little while and when I returned to my car, he followed me and asked me out for the night,” Claudia said in an in.

Claudia soon returned to San Francisco, but the couple stayed in touch.

“I didn’t think much of it. I thought she’d go back. I figured if he liked her, he’d fly and get a ticket to go out there. He loved her from day one,” Tank said.

During his time in South Africa, Tate accumulated a $12,700 phone bill. More than half of that was from conversations with Claudia. Most lasted well over an hour.

After his loss to Weaver, Claudia took a two-week leave of absence from her job to comfort John. Those two weeks turned into two months.

Tate was on his way to drop Claudia off for her return flight to California when it happened...

“All of a sudden, he just swerved onto the shoulder of the road, reached into his pocket and handed me a box,” Claudia said.

The couple was married on Sept. 24, 1980, in Reno, Nevada.

With a new bride and restored vigor, John was ready for his comeback.

Listen to a 1981 radio interview with John Tate:

“He said, ‘Hey, I got caught a couple times, man. Let’s don’t give up on this thing. I want my belt back.’ So, we made a comeback, and we were doing very well,” Ace said in a later interview.

Over the next three years, John and Ace racked up 10 wins in a row, enough to earn another shot at the Heavyweight Championship of the World.

In early 1984, Tate was set to take on newly crowned International Boxing Federation Champion Larry Holmes.

“Most champions, when they lose, get a second chance. I feel that Tate deserves that chance. I’ve taken opponents too lightly in the past. I can’t do that with Tate. I’ve got to go in there and get him outta there as fast as possible,” Holmes said.

Tate, now 29 years old, felt he was a more complete fighter.

“I’m a better boxer now than I was then. I feel that I’m at my peak. Holmes is ready when he gets in the ring. Even though he’s been in trouble a couple times, he has been able to rally and win,” Tate said.

The fight was set for April 6, 1984, in Reno, Nevada. Holmes would receive a cool $3 million to Tate’s $250,000.

Then in a tragic turn, Tate suffered severely strained muscles in his shoulder in a pre-fight sparring session.

“He had finished four rounds of sparring with Jeff Sims and started a round with Dwain Bonds. I saw him throw a left jab, and he backed off. I asked him to throw a left hook. He did, and I saw him wince from the pain. We canceled the rest of the workout,” Ace said.

The prognosis sidelined the Knoxville fighter for two weeks. Postponing the fight, however, was not an option.

Holmes was scheduled to fight a unification bout in June against the man who now held Tate's old title, newly crowned WBA Champion Gerrie Coetzee.

“He was living in a trailer next to Golden Gloves so they were keeping him in pretty good shape. I think had he not gotten injured, he could’ve had a pretty good fight,” Kouns said.

Thus, the showdown between Holmes and Tate ended in cancellation and led to more trouble for Team Tate.

“John didn’t really understand the value of money. I saw John blow $60,000 in one week. One thing he bought was a $10,000 chandelier to put in his house. Then he bought some $9,000 speakers,” Tank said.

Tracy recalled he also had a limited-edition white Gucci Cadillac with Gucci leather trim and 24 karat gold wheels and trim.

In November 1983, unable to control his wild spending habits and fearful of erasing his entire $300,000 estate, Tate requested conservatorship of his finances be overseen by Ace.

“Dad had it set up through the conservatorship that he wanted John to have enough money to live each month and still have some money invested. He wanted him to own some properties and some things that nobody could take away from him. If he had money, he was spending it on other things and doing things he shouldn’t do,” Tracy said.

Six months later, increasingly violent misunderstandings and confrontations between the two longtime partners led to Ace resigning as conservator. The trainer felt his relationship with Tate was heading for a total disaster.

“I saw some heated arguments being in this gym between the two of them, to the point where it got worrisome for Dad. I was afraid. ‘What if he ever hurt you?’ He’d say, ‘Oh, he’d never hurt me,’ and he never was afraid of John, and I don’t think John would’ve done that, but there were some heated discussions. He wanted his money. He wanted control. I think Daddy was hurt as if he lost a child with John, but he always loved him,” Tracy said.

The Tate estate ended up in the hands of a court-appointed Knoxville lawyer.

Big John wouldn’t fight again until 1986. In the two years that followed, he competed five more times against opponents of questionable caliber.

“He really believed in fighting. He could always go back to fighting and bring more money in, but, you know, everything has an end to it,” Tank said.

For what would be his final bout, Big John and what was left of his crew flew to London, England for a match against local challenger, Noel Quarless.

“They put us up in a small castle, a six-bedroom castle that had a swimming pool and maids and stuff. Boy, it was nice,” Tank said.

For Tate, however, the trip to London was more vacation than business.

“We would weigh John in every morning, and he would always gain about eight and a half pounds, and we couldn’t figure it out. Then we figured out he’s going downstairs to the kitchen at night while we sleep. So, we put a lock on the refrigerator door one night, and sure enough, in the middle of the night, 2 or 3 o’clock, we heard him down there cussing. We were at least trying to get him in some kind of decent shape,” Tank said.

Despite his poor training camp, the fight seemed like just another night at the office for Big John.

“John just about beat that boy to death. I heard people around me saying, ‘Big John’s about to kill him! He’s gonna kill him!’ and [John] lost by a half a point. He really didn’t lose that fight. He won over in England. It’s a loss on his record, of course, but it was definitely some home cooking,” Tank said.

Big John Tate retired with a professional record of 34 wins and three losses.

Big John's Fall

Throughout his 37 pro-fights, John Tate made over $2 million. By his own admission, though, in the five years between 1983 and 1988, the fighter spent anywhere between $300,000 and $400,000 on a cocaine habit.

“I was shocked to find out when I found it out. Those influences, of course, are what destroyed him as the man that I knew. That broke my heart,” Ace said.

Tracy said Tate never did drugs around the family, but they could tell something was not right.

“We saw the after-effects on John. He would come in here and you just knew that he was not himself,” Tracy said. “I never saw him do drugs, and he never did drugs in front of Daddy ever.”

As John’s habit grew, his behavior became more erratic.

“Acting like things had gotten robbed at his house. ‘Somebody broke into my truck.’ Then come to find out that he had taken a bat and broke the windows himself to stage a robbery so he could get insurance money so he could get more money,” Tracy said.

In a March 1988 Knoxville News-Sentinel article, Tate recalled going so far as to give a drug dealer an $18,000 Rolex watch in exchange for a pound of cocaine.

“I was supposed to go back and get my watch and take him $14,000 in cash, but I never did. I already got what I wanted. I’ve been in the ring with some big men, but none of them beat me the way drugs did,” Tate said.

With his money still under a conservatorship, Tate sought control of his estate, now valued at less than $200,000, claiming he and his wife were only receiving $200 a week for living expenses.

A judge denied Tate’s request in December 1988. Soon after, John and Claudia were divorced.

“I took him up there to the lawyer’s office, and they signed the papers and did whatever they had to do. Then he got in the car with me, and as she was going down the hill, the light caught me on Gay Street. So, he was kinda, ‘There she goes, Big Man. There she goes,’” Tank said.

By the start of the new decade, Tate found himself living on the streets.

“He said, ‘Anytime you need me, I’m back here in this car.’ He was living in a car at a car lot,” Tank said.

Although their professional relationship ended years prior, the Miller family still extended an olive branch to John whenever they could.

Tracy said John showed up one Thanksgiving in the middle of dinner. When Ace went outside, Tate refused to come in.

“He was in a really bad way with the drugs, and Dad took him to a rehab facility and got him checked in then moved into the gym down here with him and stayed for about six months trying to get him straight,” Tracy said.

Despite Ace’s best efforts, things would only get worse for Big John.

Between July 1990 and 1991, he was arrested three times for allegedly selling cocaine, failure to appear and public intoxication. In 1992, Tate was jailed another three times for probation violations.

In March 1993, however, John Tate was convicted of aggravated assault for breaking a man’s jaw. He claimed the victim owed him $40, and during their encounter at Austin Homes, the victim told John that he was going to do to him what Mike Weaver did to him.

“When he said that, and owing me $40, I just didn’t digest that too good,” Tate said.

During the hearing, the prosecutor asked John if he thought the victim was going to knock him out.

“No, but I didn’t think Mike Weaver was going to knock me out either,” Tate said.

Big John Tate spent 28 months in jail. During a March 1994 interview, a now 400 pound Tate told reporters at 39 years old, he was using his time in jail to finally learn how to read.

“The most embarrassing thing that’s ever happened to me in my life was when I heard Howard Cosell say on national television, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, this man is illiterate.’ Learning how to read is equal to winning the Heavyweight Championship of the World. I have lived for more than 35 years without learning how to read. Now, everything I come in contact with, I try to read. Sometimes I read it over and over and over,” Tate said.

Even after his release, Tate could still be found panhandling in Downtown Knoxville.

Tracy said it broke her heart the first time she saw him charging $2 to park cars in a vacant lot in the Old City.

“The police came by and said, ‘John, this isn’t your car lot. You can’t be charging people to park cars here.’ He said, ‘No! I’m not charging them to park the cars here. I’m charging them for the former Heavyweight Champion of the World to wash their car while they’re doing what they’re doing,’” Tank said.

Kerry Pharr, a trainer out of Smyrna, Tennessee who managed local heavyweight contender Keith McKnight, reached out to Tate during his time at Brushy Mountain Prison in hopes of helping him make a comeback.

“I contacted the prison, got on the visitor’s list, went up there and saw him," Pharr said. "We were going to work together, but evidently, the street got him before I did."

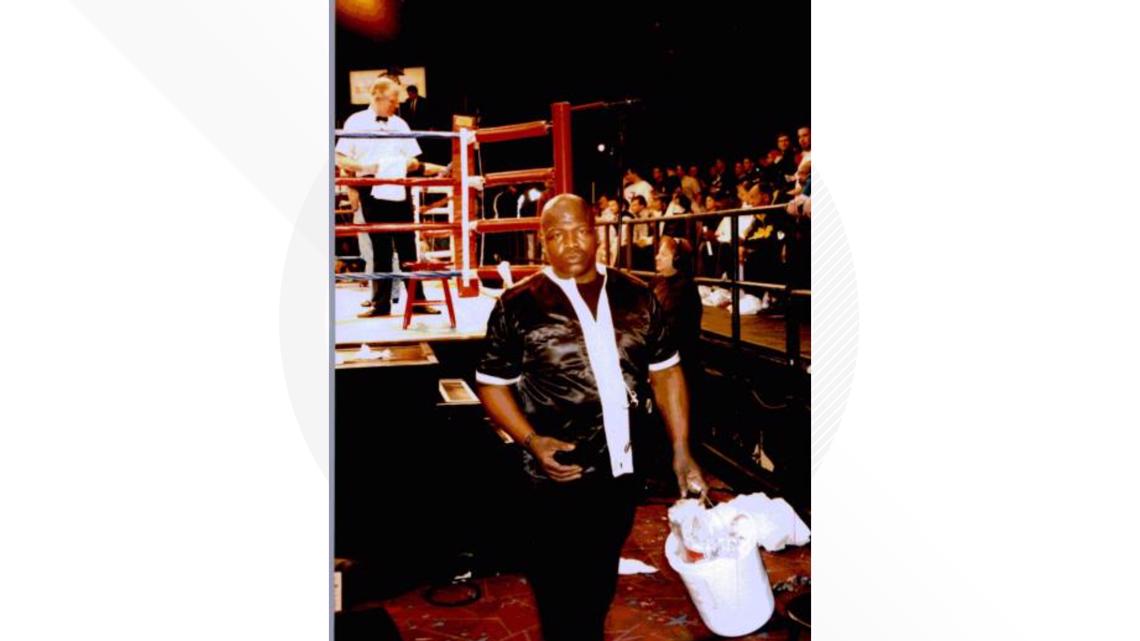

Although his attempt was unsuccessful, a happenstance meeting years later would see Big John in the ring once again. This time as McKnight's cornerman.

McKnight was set to fight the No. 4 heavyweight in the world, Obed Sullivan, so Pharr drove him to Knoxville to spar with Shazzon Bradley, an undefeated heavyweight and a former UT football star.

“While we were in the gym, a vagrant walked off the street. A big 6’3, 275 pound vagrant with dirty clothes and just a mess, and it was the former Heavyweight Champion of the World, Big John Tate," Pharr said. "I thought, ‘Man, if we had the former Heavyweight Champion of the World in [McKnight's] corner, that would really encourage him."

Wanting to give Tate another chance, Pharr brought him out to the training camp, put him up in an apartment and provided clothes for the disheveled former pugilist.

“He didn’t do a lot. I still held the hand pads and I still worked with Keith, but he gave advice and would tell Keith what to do. You know, we never had any issues with him at all. We just had a lot of fun,” Pharr said.

According to Pharr, Tate was clean and as straight as an arrow for the duration of the camp. The night of the fight, Big John seemed happy to be a part of the action again.

“Big John was in the corner with us, and he was signing autographs. People would say, ‘Hey, Big John Tate! Former Heavyweight Champion of the World!’ He’d say, ‘Yeah, I was the baddest man on the planet for a minute!’ and that was his signature line,” Pharr said.

On the way back from the fight, after Tate received his payment, he made a vexing request to Pharr.

“I was actually going to put him on the bus back to Knoxville. I don’t remember what I paid him. It was several thousand dollars in cash. He stuck the money in his pocket. As we drove downtown Nashville towards the bus station, we passed the projects on Lafayette Street, and he said, ‘Kerry, stop the car and let me out here.’ I said, ‘No, Champ, you don’t want to get out here.’ He said, ‘Yes, I do.’ I stopped the car, and he said, ‘Look, call me if you have anyone else I can work with.’ He got out of the car. Well, I knew he was going to buy drugs,” Pharr said.

One night when the former world champion was on the brink of succumbing to old demons, he called his trainer, Ace Miller.

“He said, ‘Coach, was I a good fighter?’ I said, ‘John, you were Heavyweight Champion of the World.’ He said, ‘I’m gonna be an even better bum,’” Ace said.

On April 8, 1998, two months after last stepping in the ring, Tate was working a shelf-stocking job at the Express Mart on Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue. He left around 10 p.m.

From there he went to his favorite university tavern, Charlie Peppers, dined on a meal of chicken wings and fries, then left around 1:30 a.m.

“He was in a great mood. We had a Caribbean band playing. He was enjoying that. He got some food and left, said goodbye and gave me a hug. He was always real friendly,” said Ian Roach, an employee at Charlie Peppers.

Two hours after leaving the bar, Big John Tate was dead at 43 years old. The pick-up truck he was in hit a telephone pole and flipped on Asheville Highway.

Medical reports showed Tate suffered from a brain tumor that triggered a stroke.

Watch WBIR archive videos from April 9, 1998:

Ace was the first person authorities called.

“It was really a sad ending, quite frankly, to a guy that this family of mine and Golden Gloves worshipped and endorsed. We never dreamed that would ever happen. I always thought John Tate would be my pied piper of boxing,” Ace said.

Big John Tate is buried in Crittenden County, Arkansas, where this history maker was born.

Remembering Big John

In 1979, the Knoxville News-Sentinel named John Tate the Athlete of the Decade.

In 1980, he was honored by the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame.

Then the years began to slowly claim Big John’s legacy.

Photos: Big John Tate's awards and recognitions

“We have short memory spans. Unfortunately, I think Big John has been largely forgotten. I saw Big John as an up-and-coming figure that would be here for years with his boxing career,” said Booker, who got to know Tate in local taverns and bars.

Booker started the scrapbook, “The Rise and Fall of Big John Tate,” and chronicled every picture and article that appeared in the newspapers about him. The scrapbook is currently housed in the Beck Cultural Exchange Center’s archives.

“He should still be celebrated for what he did accomplish. You think about the World’s Fair being here to the ‘Scruffy Little City on the River’ they said, and for Big John to win the World Heavyweight Championship in South Africa and to help cause the first integration of the stadium in South Africa and create so much awareness of what was going on. He just accomplished a lot. Why wouldn’t you want to remember that?” Kouns said.

Tracy, who now manages "Ace" Miller Golden Gloves Arena where Tate trained, said the kids who come in today do not know his name.

“If you compare that to somebody and you say, Evander Holyfield or Mike Tyson or Roy Jones, who are more prominent names, they all boxed in this gym, in that ring right there. People know their names, and they don’t know John. If they do, they only know the bad," Tracy said. "The John that fell on hard times was still sweet and kind. I don’t think he was ever mean. It was hard to see him in the ring and box the way he did with the talent that he had because of his kindness. It’s not like he was vindictive or vicious or anything. He was just a great person.”

Golden Gloves near Knoxville’s Chilhowee Park is a free program for people of all ages and experience levels. Tracy said she provides all the equipment needed including hand wraps, mouthpieces and gloves. She also provides snacks and drinks and covers any required expenses.

If you would like to help Golden Gloves, you can mail donations to the Ace Miller Golden Gloves Gym at 6115 Strawberry Plains Pike, Knoxville, Tennessee 37914.

“Most of the kids we have in this program are from East Knoxville. They don’t have anybody else. They don’t have anything else. To me, I relate to that because that’s what John came from, and I want them to know that if you work hard enough and you apply yourself, you too have a chance to do something in your life. John became Heavyweight Champion of the World and what he did was amazing,” Tracy said.

Judge is an amateur boxing trainer at Golden Gloves now.

“I think he didn’t get his just due because most of the people that were outside looking in, all they saw was him falling with Weaver. That’s all that was talked about. It wasn't nice,” Judge said. “People on the outside don’t know what goes on on the inside. This is a lot of work in here. He put a lot of work in to get the title shot. If people go back and watch some of his old fights, people will see that John was a very good boxer, a very good boxer. You have a short career in this sport, and you don’t know when it’s going to end. You don’t know how far you’re going to go with it, but he did well.”

The world heavyweight title dates back to 1884. Since then, only 82 men have earned the right to call themselves the Heavyweight Champion of the World.

One of them is from right here in Knoxville, and his name is Big John Tate.

For a behind the scenes look at the documentary you can watch The Making of Knoxville's Forgotten Champion.

You can find more about Big John Tate on our YouTube playlist: