The Knoxville Giants: The Negro Southern League in the Scruffy City

Before Jackie Robinson broke the Major League Baseball color barrier, Black athletes started the Negro Leagues, and Knoxville’s team was swinging for the fences.

Out of the shadows of the Civil War arose America's favorite pastime in East Tennessee. From the farm leagues to the Tennessee Smokies, baseball ingrained itself in Knoxville’s history, and 100 years ago, a team of Black men stepped up to the plate in an East Knoxville ballpark and became champions.

“There were five teams mentioned from the Knoxville area. One of them was a colored team, the Knoxville Eagles,” said Mark Aubrey, a baseball researcher. “From that, there’s been baseball off and on, both professional and industrial leagues, but there were also Negro teams. They weren’t part of a league. They were mostly independent teams, and they would play other colored teams.”

The Negro Southern League

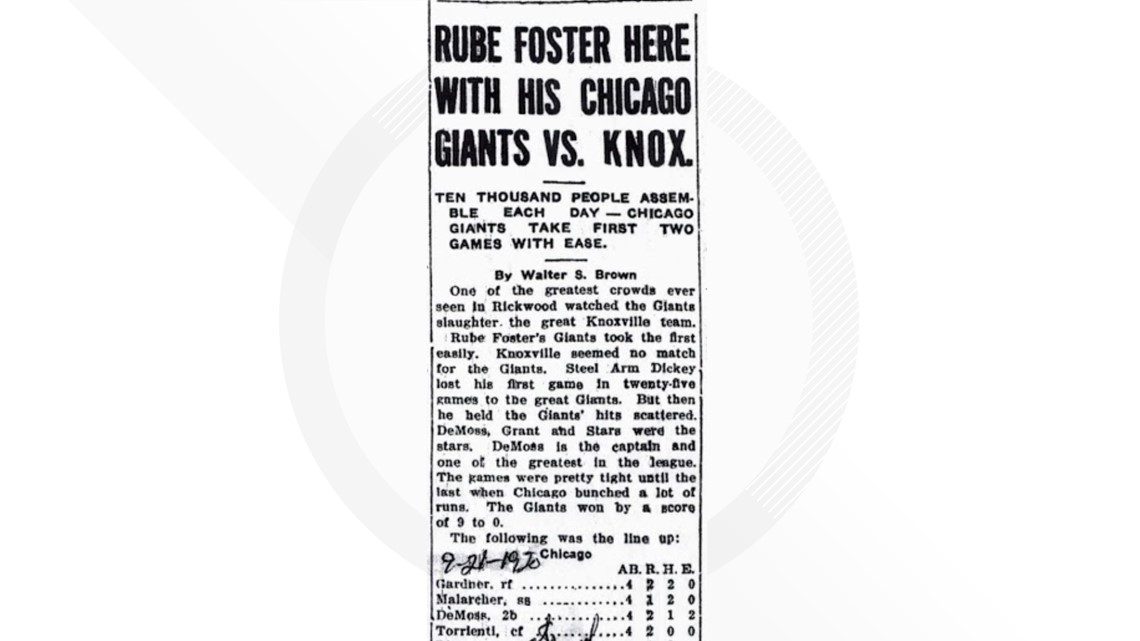

On Feb. 13, 1920, future Hall of Famer Andrew “Rube” Foster and a group of team owners started the Negro National League in Kansas City, Missouri to give Black athletes the chance to play organized baseball.

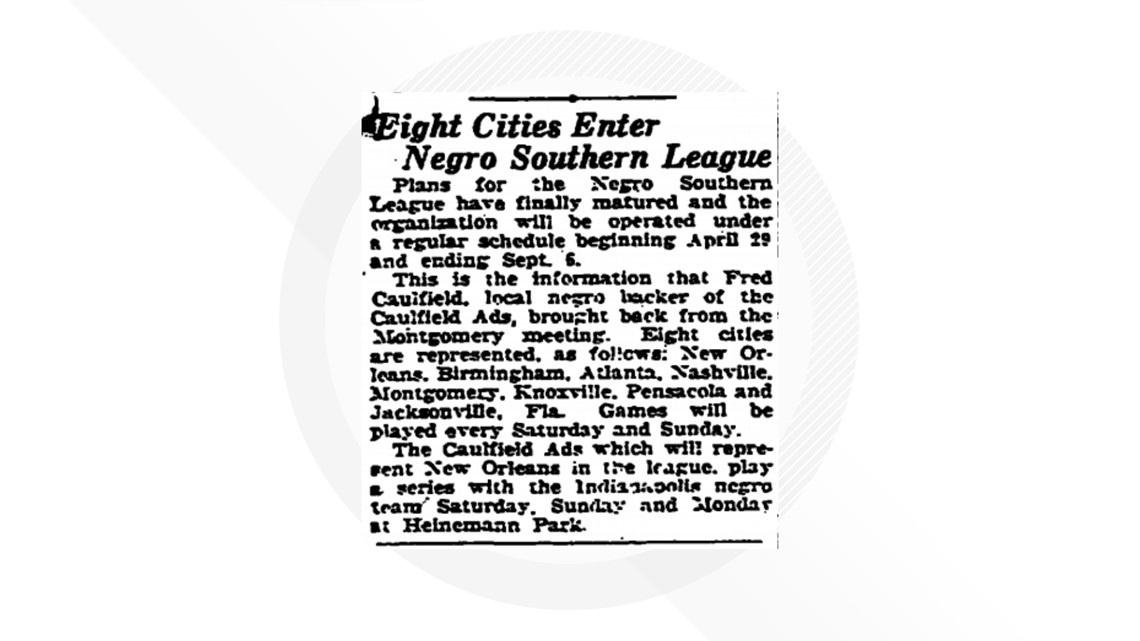

A month later, in March 1920, a group gathered in Atlanta, Georgia to create a league of their own. Two men from Knoxville, William Brooks and Monroe Young, attended the meeting to claim East Tennessee’s spot in the league.

“That was the beginning of organized Black baseball in the south,” said Bill Plott, a retired journalist and the author of “The Negro Southern League: A Baseball History, 1920-1951.”

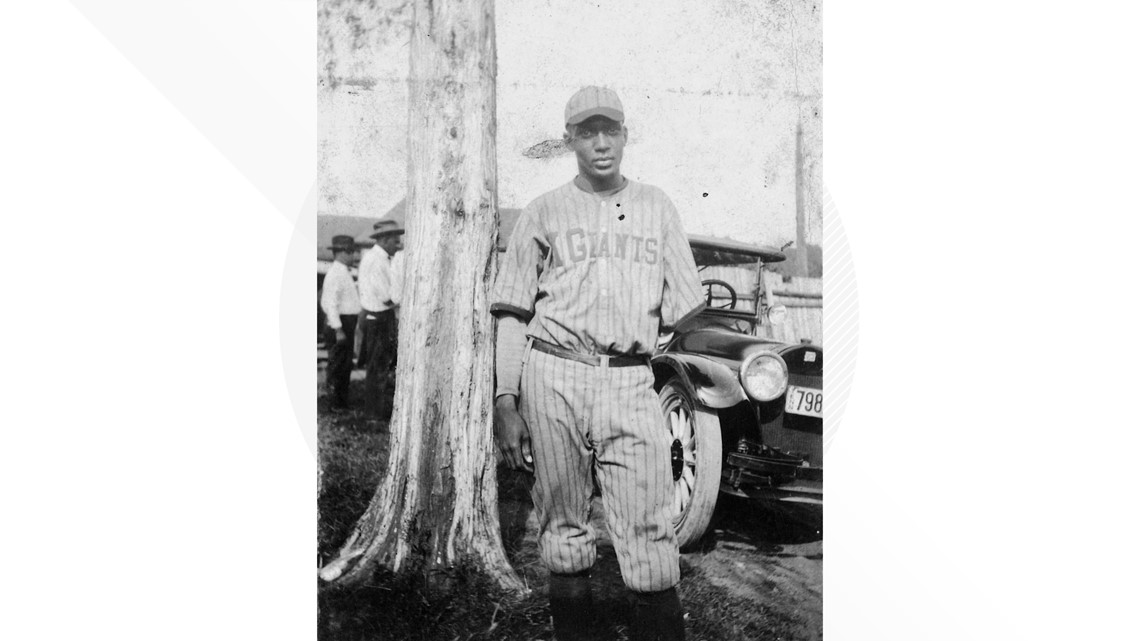

Eight teams formed the Negro Southern League (NSL): Atlanta Black Crackers, Birmingham Black Barons, Jacksonville Stars, Montgomery Grey Sox, Nashville White Sox, New Orleans Caulfield Ads, Pensacola Giants and Knoxville Giants.

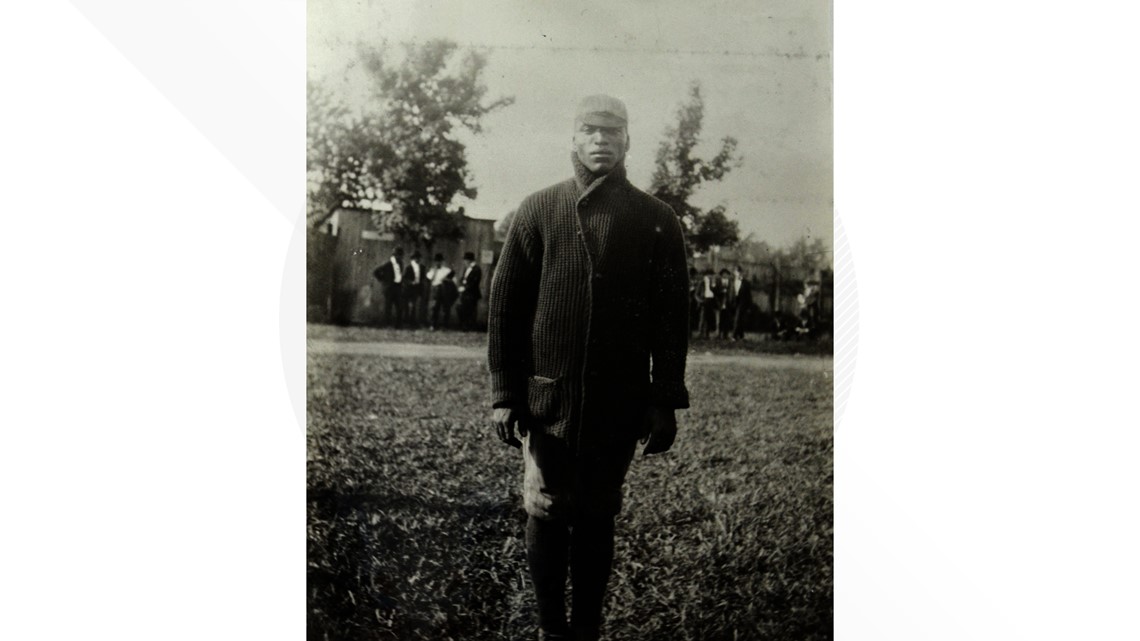

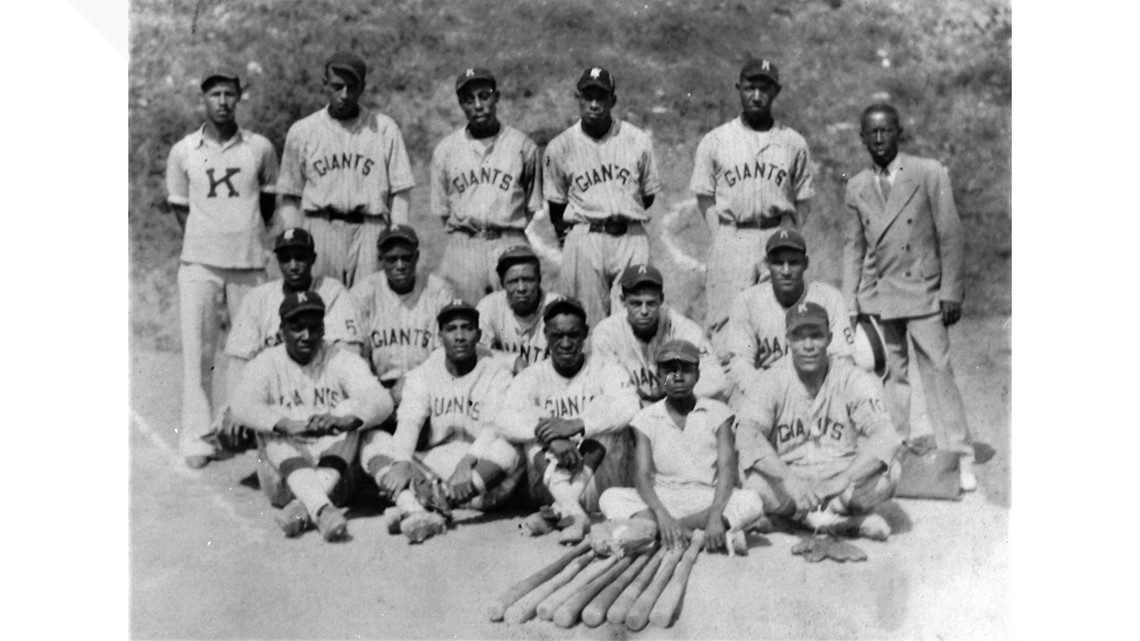

“They were a strong club. They were already established as the Knoxville Giants going back a couple of years to the mid-1910s,” Aubrey said.

With Brooks named the first NSL secretary and the team’s manager, the Giants were ready to play ball.

The First Season

The Negro Southern League season opened on April 29, 1920.

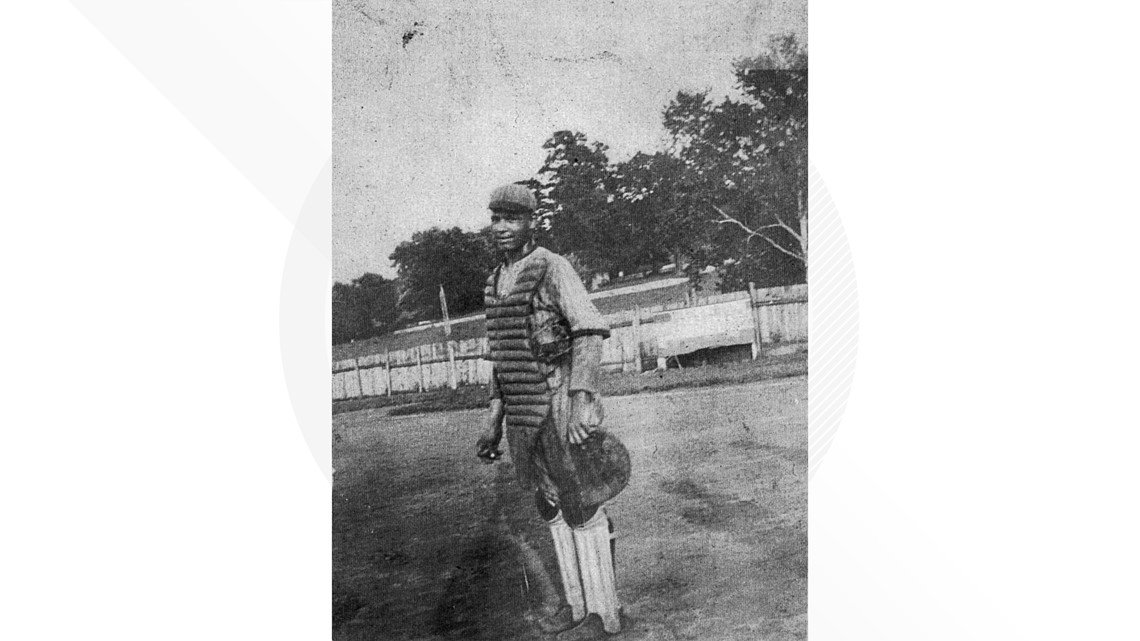

Knoxville faced off against Nashville at Sulphur Dell, where First Horizon Park now stands, beating them 6-2 thanks in part to a standout pitcher named Walter “Steel Arm” Dickey who held the White Sox to four hits.

Soon after, the Giants took on Jacksonville for their home opener at Brewer’s Park, later known as Booker T. Washington Park. They beat the Stars 8-4 with Steel Arm striking out eight batters.

“He went the distance. Back then, you rarely had two pitchers pitching like now in modern baseball,” Aubrey said. “Back then, it was you pitch the whole game. You pitched the complete game, but that's what it was.”

The Giants played over 100 games throughout their first season, taking on teams in and out of the NSL and traveling roughly 5,500 miles.

“They started playing in, I believe it was, April, finished up in September, and it was quite a season,” Aubrey said.

While Steel Arm’s pitching made national news, especially as he began a long winning streak, some of his teammates were quickly becoming league stars in their own right.

Players like Forrest “One Wing” Maddox, a pitcher and outfielder who lost his left arm as a child, were a boon to the 1920 Giants.

“He would catch a ball with his right hand and the glove then flip it like this to get the ball up in the air, sling off the glove, catch the ball as it came back down, and then throw it into the infield,” Plott said. “On more than one occasion, he was credited with putting runners out on home plate, who were trying to get home thinking he couldn’t throw the ball in, but he had a very, very strong arm.”

The Giants also had an ace in first baseman Ralph “Pete” Cleage who, based on the data available from that time, would be the Negro Southern League’s best hitter by the end of the 1920 season.

“Pete was an outstanding player and a very good hitter,” Plott said.

The 1920 Giants also had future Hall of Famer Norman “Turkey” Stearnes on the team for a few games.

With these stars on the roster, Knoxville continued to win series after series, and Steel Arm claimed a 25-game win streak.

“He was unquestionably the best pitcher in the league,” Plott said.

His shot at 26 was squashed, however, on July 29 in a game against the Montgomery Grey Sox, the Giants’ biggest rival.

Knoxville didn’t lose a series until August and would regularly draw large crowds of both Black and white fans.

“It depended on how the team was doing, who the opposing team was. You may have hundreds, you might go up to thousands,” Aubrey said. “They had segregated seating. I find this in the news reports mostly of Black baseball games, ‘The grandstands are reserved for whites.’ ‘A portion has been set aside for whites.’”

The Champions

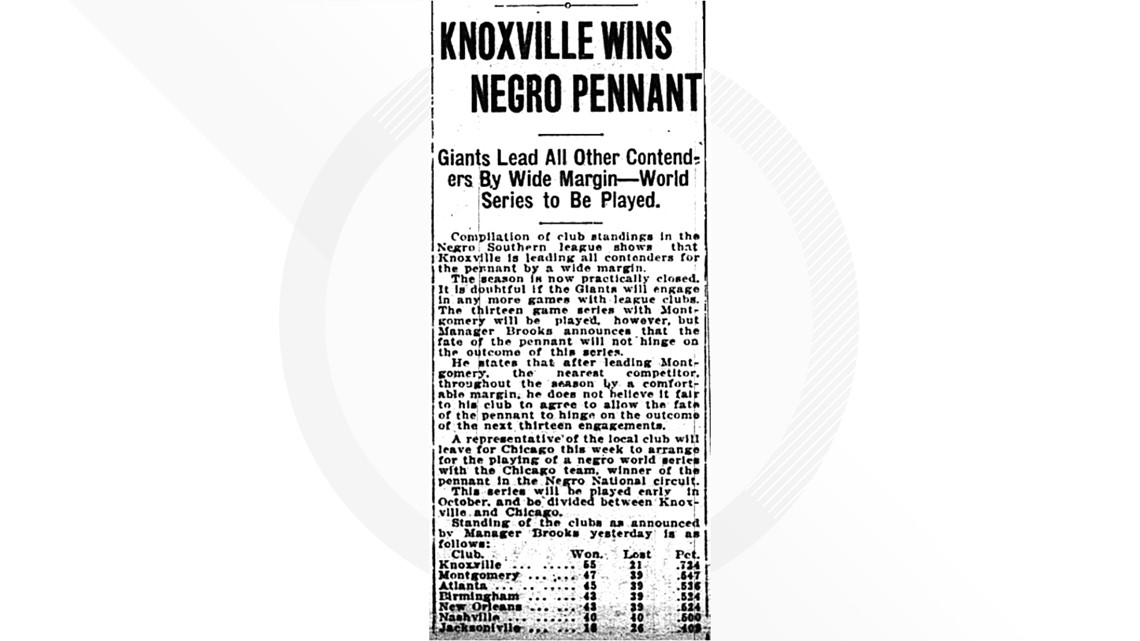

As the season drew to a close, Knoxville and Montgomery were the clear frontrunners, but a claim at the championship title proved to be controversial.

“The 1920 season was a battle between Knoxville and Montgomery the whole year, and they swapped the lead back and forth,” Plott said.

Birmingham-based NSL President Frank Perdue declared Montgomery the league champions, but standings published in the Knoxville Journal and Chicago Defender showed the Giants as the champs. Knoxville went to Montgomery and offered up a series to determine the winner.

“Montgomery didn't like that so, basically, Knoxville declared themselves champions,” Aubrey said.

The true 1920 champion remains contested as some teams played more games than others during the season and the spotty record-keeping tended to skew toward the hometown favorite.

“I guess I will admit to my prejudice, being an Alabamian and leaning toward Montgomery, but at the same time, if you want a claim for Knoxville and say Montgomery disputed it, I have no argument with it whatsoever because it was impossible to actually come up with a definitive answer,” Plott said.

Aubrey, an East Tennessean, said the Giants claimed the title.

“I think that Knoxville won based on their head to head with Montgomery and their overall record,” he said.

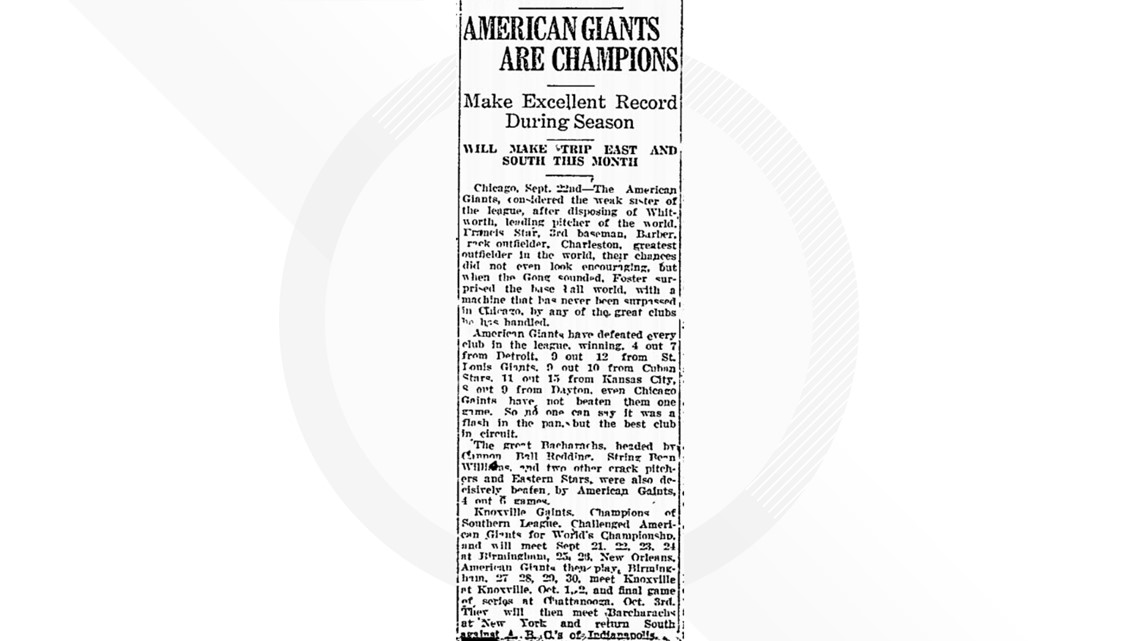

Knoxville sent its team secretary, Monroe Young, to meet with NNL founder Rube Foster, who owned and managed the Chicago American Giants.

“He said, ‘You guys are the champions of the NNL. We're the champions of the NSL. What do you say we play a colored World Series?’” Aubrey said. “So there's some validity if you have a champion of the Negro Southern League playing the champion of the Negro National League. It wasn't Montgomery. It wasn't Birmingham. It was Knoxville.”

The series was set to host games in Birmingham, Chattanooga, New Orleans and Knoxville in what Aubrey described as a “barnstorming exhibition.”

“It did not go well for Knoxville. Not at all. The five games that we know were played, they lost all five. First one was by forfeit. Something went wrong. Knoxville stormed off the field. The umpire says, ‘No, that's the game,’” Aubrey said.

Montgomery did eventually play the American Giants with the Montgomery newspapers claiming the Grey Sox as the champions of the Negro Southern League and referring to their two-game series with Chicago as the world championship.

“[The Chicago American Giants] swept the three-game series with Montgomery and then went to Birmingham and won two games against the Black Barons, so they were undefeated in the south,” Plott said.

Giant Memories

The following season, the Knoxville Giants placed last in the NSL standings.

“You had players move on. Steel Arm Dickey wasn’t with them in ‘21,” Aubrey said. “Other teams got better players. You lost the drive a little bit.”

Plott said the Giants’ roster between the two seasons was a clue.

“In 1920, the Giants had used about two dozen players total for the whole season that I was able to ascertain really played on the team. In 1921, there were way more than 60 players, which indicates they had a hard time finding a winning lineup that year,” he said.

Then, at the end of the 1922 season, the Knoxville Giants fell away from the Negro Southern League as an independent team.

“The team kept playing,” Aubrey said. “You had a couple gaps in there for years of the Negro Southern League just not being in existence. They either folded early, didn’t have enough teams to make a league. Ownership in the mid to late ‘20s, there was an argument over the team name and later on who owned the team.”

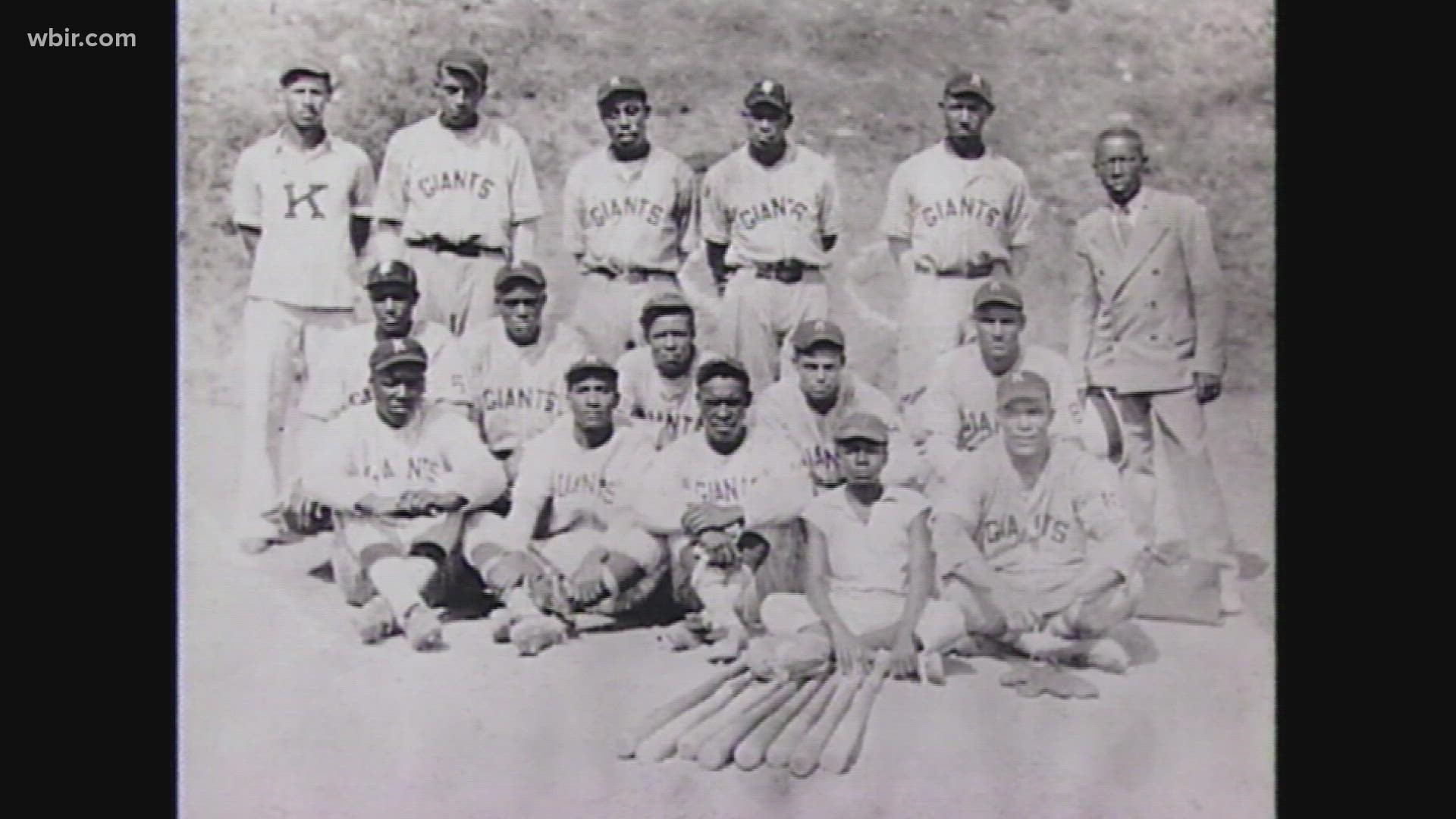

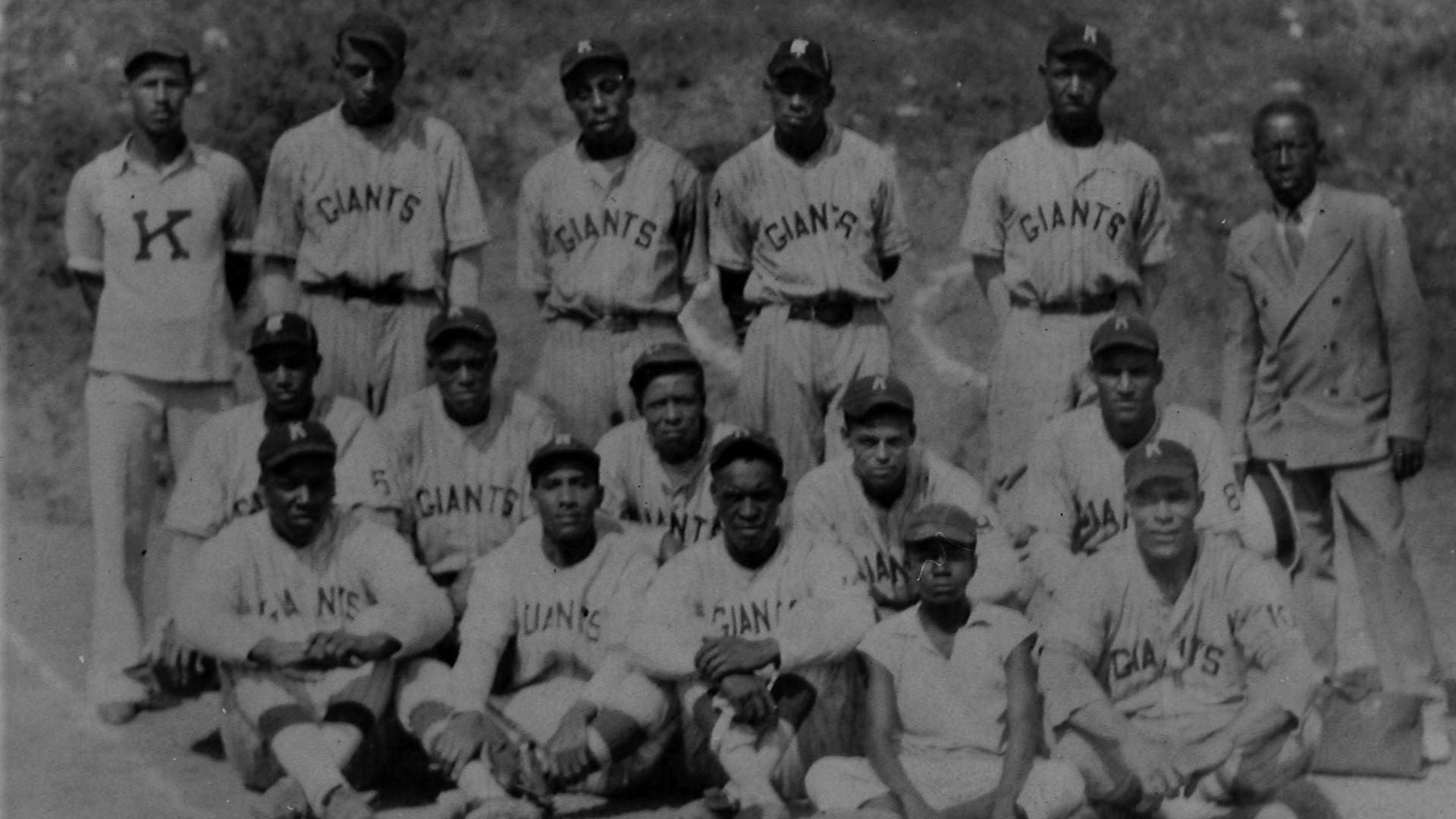

Although no longer affiliated with the NSL, the players’ passion never waned as evidenced by their memories in a 1993 interview featured on WBIR’s The Heartland Series.

For an extended interview with the former Giants players, click here.

“Everybody contributed. Everybody played well,” said Ralph Banks, a former Knoxville Giants right fielder. “A balanced team for one thing. It wasn’t dependent on one man to do it all. No special, no star or nothing.”

Unlike the Giants of the Negro Southern League, which drew players from all over the region, the independent team’s dugout was full of local boys who knew how to play ball. So local, in fact, one remembers watching the 1920 Giants play.

“My brother carried me to see them play. I was just 9 years old, and he carried me to see them. That was when Steel Arm was playing back then,” said Leroy Bowerman, a former Knoxville Giants pitcher.

The team’s camaraderie extended off the field and even to the opposing teams.

“We just got along fine. We go play a game of ball, get through and go take a bath. Maybe we'll go down to the pool room, sit around, talk and laugh, shoot a few games of pool,” Bowerman said.

When a visiting Indianapolis team couldn’t afford to make it back home, the Giants extended a helping hand.

“We played them on Friday and Saturday, beat ‘em. They wanted to stay over and we played ‘em Sunday and Monday and beat ‘em Sunday and Monday, and then they was to go leave Monday and couldn’t leave, didn’t have enough to leave on,” Bowerman said. “We had to give ‘em money to get gas with because they had two cars.”

They played local teams, both Black and white, walking from ballpark to ballpark in city limits if the Giants’ winning streak didn’t scare off an opponent.

“We got real good, you know, and then we got to where we couldn't get a game. You know, we got so good we couldn't. They’d say, ‘Well, we can't beat ‘em. You don't need to.’ Or other teams would say, ‘We’re so good. We can't beat them so there’s no need to play them.’ They wouldn't. We could hardly get a game. We had a game with the Smokies once, and we went out there and they wouldn't play us,” Bowerman said.

Bowerman also said his biggest thrill with the Giants was the chance to play the Ethiopian Clowns, a Miami-based barnstorming team.

“They were the best team we ever played,” he said.

When a game took them on the road, the team piled into two or three cars, slept in houses or hotels and ate meals with the opposing team.

Their earnings came from whatever was left after expenses were paid.

“Two dollars, three dollars, sometimes four, sometimes nothing. We wasn’t playing it for money; we just played it because we liked it,” said Ernest Waters, a former Knoxville Giants pitcher.

Despite the Giants’ prowess and popularity on and off the diamond, major league dreams were still more than a decade away for Black players.

“We didn't have a chance to get in the big league. I didn't know of any Black people that was in the big league at that time,” Bowerman said. “There weren’t no better players than we were back then. We were ‘bout the best players that I knew of back then. There wasn’t no way.”

End of the Negro Leagues

Plott said coverage of the Negro Leagues began to slide as newspapers turned their attention to groundbreaking Black athletes like Jackie Robinson when he broke the Major League Baseball color barrier in 1947. The Negro National League ended in 1948.

Knoxville would reappear under different names in the Negro Southern League off and on in the 1930s and ‘40s before the league officially dissolved in 1951. Historians point to a Knoxville Packers box score as the last known record of an NSL game.

“It was a shell of itself. Of course, by that time, baseball was integrated. Minor League Baseball was up and running,” Aubrey said. “Baseball life was changing.”

The players moved on as well.

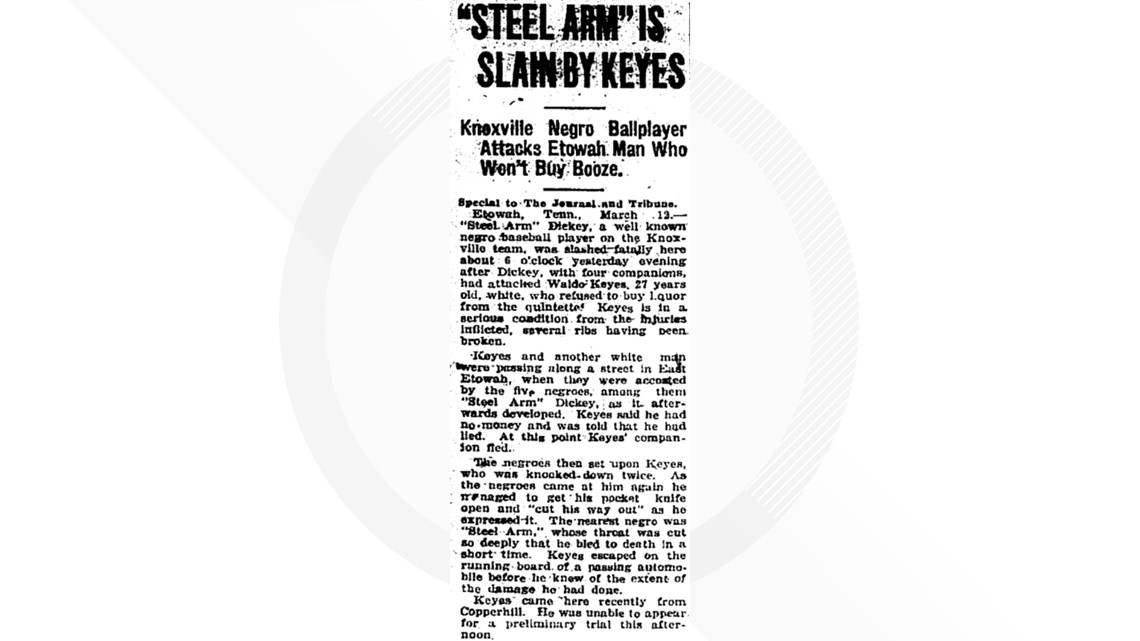

Steel Arm left the Giants in 1921 to pitch for the Birmingham Black Barons and the Montgomery Grey Sox and briefly pitched for the NNL St. Louis Stars before returning to Knoxville for the 1922 season. His career was cut short in 1923 when he was killed in Etowah during a scuffle over moonshine. The details are contested.

“It was in a sundown town, and something went horribly wrong. A fight broke out. Steel Arm Dickey was slashed in the neck, and he soon died. Three or four white men were taken into custody and charged with his murder,” Aubrey said. “Then through the court system, and I'm sure some pressures from outside influences, Steel Arm Dickey and his friends were then accused of instigating and the white men were cleared.”

One Wing Maddox went on to pitch for the Birmingham Black Barons and Washington Braves. He was then a professor at Morehouse College in Atlanta before dying of tuberculosis at 31 years old in 1929. He was buried in Atlanta's historic South-View Cemetery.

Pete Cleage managed the Giants for a time and played for the St. Louis Stars in 1924. He went on to notoriety as an umpire in the Negro National League in the late 1930s. He died in 1977 and was buried in Knoxville’s Crestview Cemetery.

“They weren't all just flashes in the pan. They may have been a flash in the pan for their baseball career, but several had long careers outside of baseball,” Aubrey said.

Legacy

Now, more than a century after the Knoxville Giants declared themselves champions of the Negro Southern League, historians are working to give new life to their legacy.

“There’s been a national recognition of Black baseball, of the injustices that those players suffered during those years, and I think you’re seeing now that there’s a reconciliation. I’m glad to see the recognition accorded to these people. They played an important role in their communities, providing a cultural center and entertainment and hopes for a better future,” Plott said.

In the 2013 Rickwood Classic, a minor league game played every year at baseball’s oldest professional ballpark in Birmingham, Alabama, the Birmingham Barons hosted the Tennessee Smokies in an homage to the Negro Southern League. The Smokies’ uniforms echoed those worn by the 1935 Knoxville Giants.

“This is amazing. Just looking at all the seats and all the memories that must go with the Negro League players that played here, it’s just amazing to be here,” said Tim Torres, a former Smokies second baseman in a video produced by the team at the time.

Currently, the Beck Cultural Exchange Center is working with developers on the new stadium coming to Knoxville to highlight the area’s history. The Knoxville Giants are featured among the notable names from the section of town known as The Bottom.

“The Knoxville Giants are critical to our history because they set the tone and the pace for our community to say, ‘There are great ballplayers, there are great people here who want to play the game and who are good at the game,’” said Reverend Renee Kesler, president of the Beck Center. “I want us to remember the Giants as a team who came together, who believed in what they could do, who worked very hard, and set the tone from the very first year right out the gate, that Knoxville has some extraordinary people, and we are a force to be reckoned with.”

As a historian and baseball fan, Aubrey hopes visitors learning about the team will help uncover more information to preserve the Giants’ stories.

“It's a legacy that keeps on giving, and hopefully for the inquisitive minds, they will dig deeper into it,” Aubrey said. “They were groundbreakers on a local level, on a smaller level. They weren't Jackie Robinson, but they loved what they were doing.”

For the players, it was all about the love of the game.

“I've played in many a game and didn't get a dime, but I just loved to play ball. I could play and I know it, and I played because I knowed that I could play,” an 86-year-old Bowerman said in 1993. “I liked to play with ‘em because it was an enjoyment to me to get to play.”

Resources

In 2020, Major League Baseball officially added the Negro Leagues to its records, meaning around 3,400 Black players were now major leaguers including several former Knoxville Giants. The MLB gave special recognition to the Seamheads Negro League Database.

Historians continue to uncover new information about the Negro Leagues and the players. Aubrey has a blog called Old Knoxville Base Ball. The Negro Southern League Museum in Birmingham, Alabama also has a research center.

The Beck Cultural Exchange Center archive has photos and documents about the Knoxville Giants, which will be featured in the new stadium coming to Downtown Knoxville in 2025.