KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — As the weather heated up in the year 1919, so did race relations across the country. During a period of almost six months, racially motivated violence broke out in about 25 different cities.

Beck Cultural Exchange Center President Renee Kesler said an important part of the story is rooted in World War I.

"I think understanding the temperature of that summer, in general, is important," she said. "You’re talking about the end of the World War, the first World War and you’ve got soldiers coming back from home to segregation."

She said that narrative held true all over, including right here in East Tennessee.

"Indeed Knoxville had its own story and so as history records, it becomes one of the bloodiest most violent parts of our history with respect to race relations," she said.

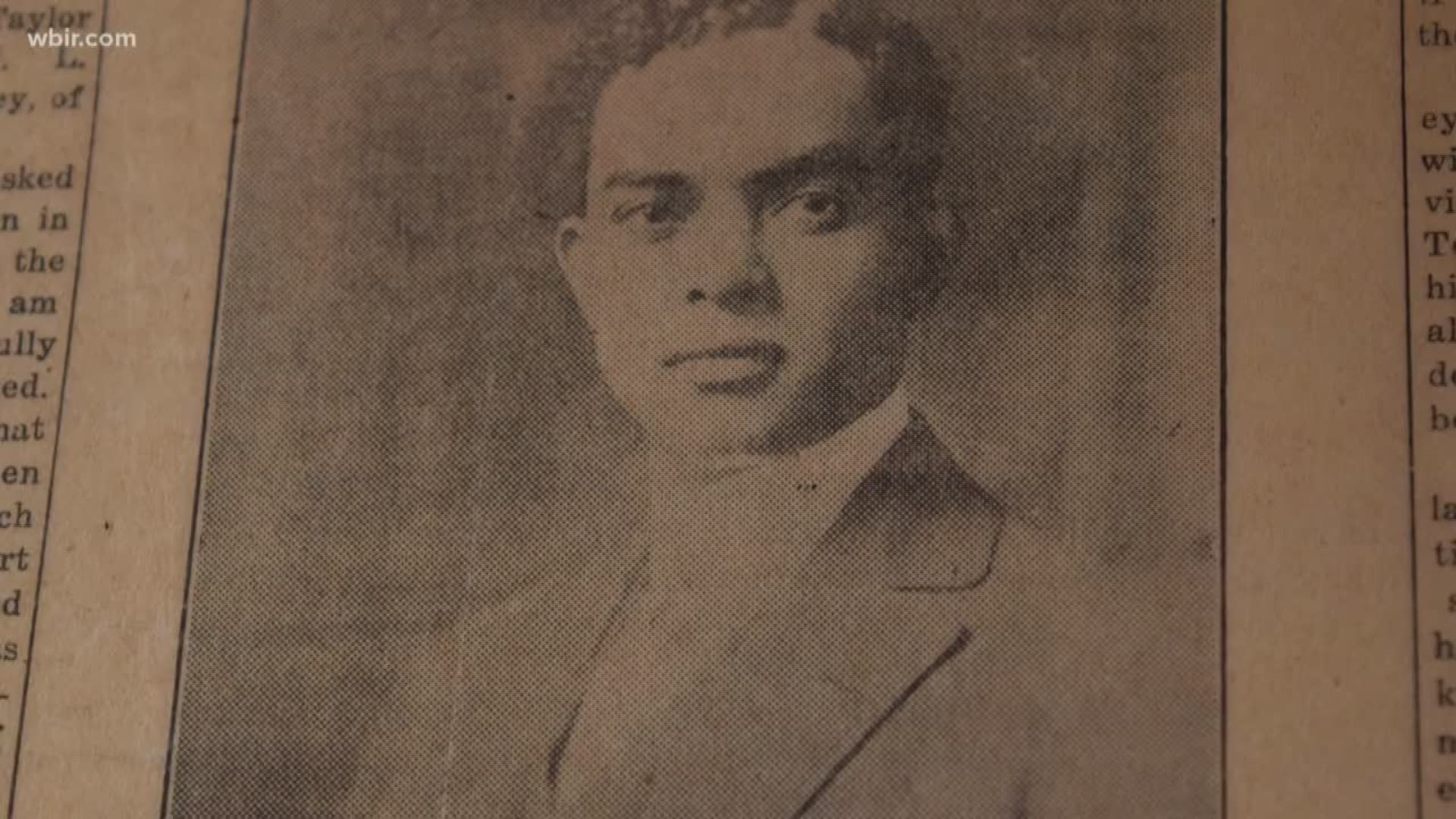

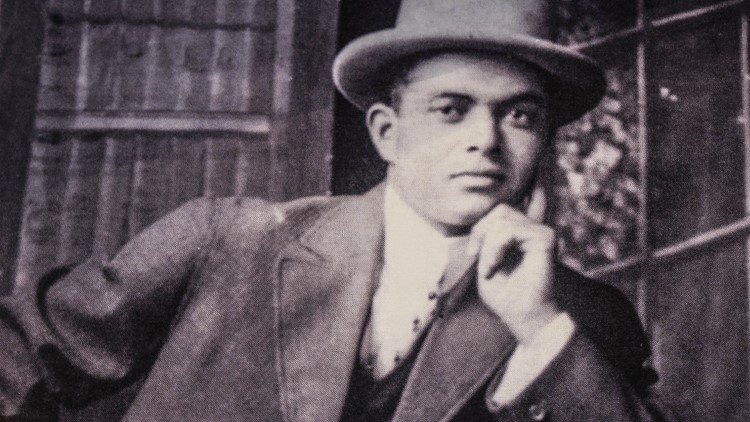

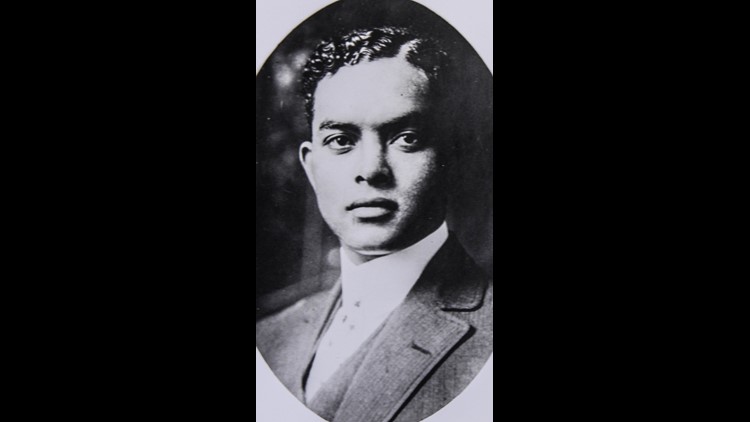

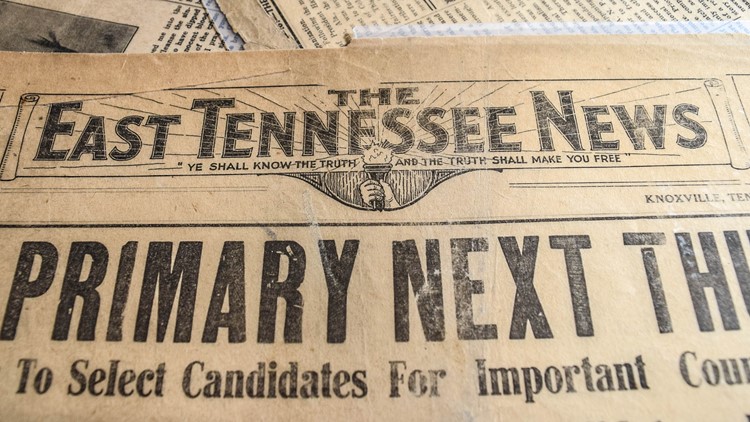

East Tennessee's story starts with one man by the name of Maurice Mays.

Photos: Maurice Mays and the 1919 race riots

"So Maurice Mays is interesting and his life was interesting from the very beginning," Kesler said. "He was a businessman, politically active, but he was also known to bend the rules."

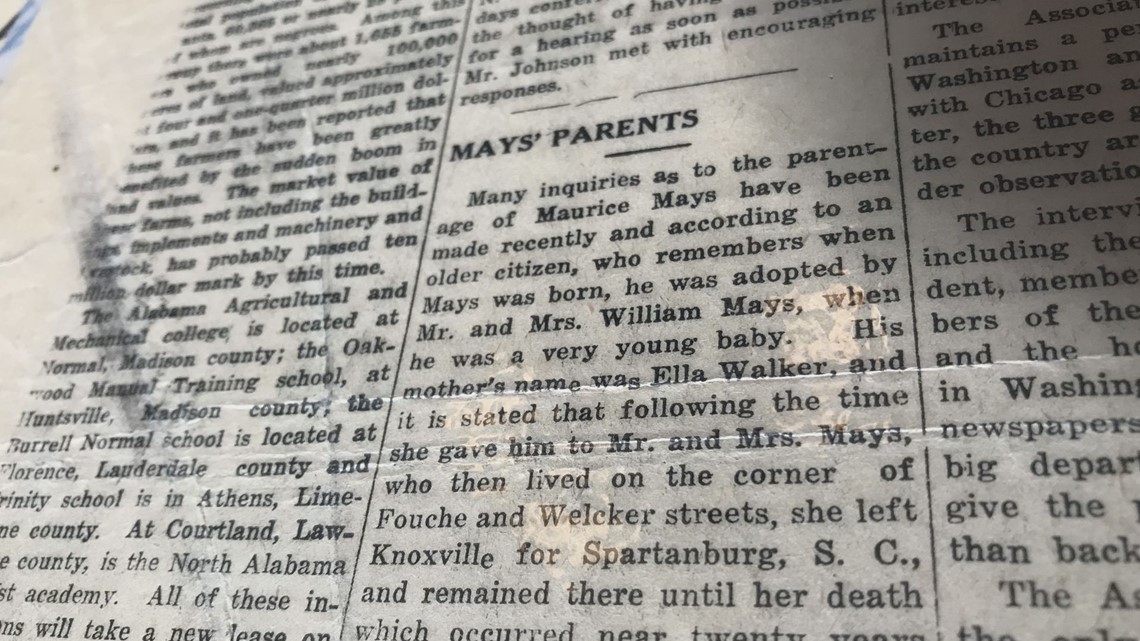

Multiple historic accounts and newspapers of the time detail how people questioned May's background.

"So the story goes that he’s actually adopted by the Mays family, a young African American family who raised him as their own child, who could not have children," Kesler said.

Historians have said his role in the community led to a few rocky relationships.

Robert Booker is the former executive director of the Beck Cultural Exchange Center. He said Mays had a particularly difficult relationship with law enforcement at the time.

"There was a white policeman who threatened him and told him he better leave white women alone or he’d end up in the penitentiary,” Booker said.

And that encounter is where the story of the Knoxville Race Riots begins.

"The story goes that supposedly this African American male kills this white female and it doesn’t take long for word to hit the streets," Kesler said.

Court documents show on the morning of Aug. 30, 1919, a woman was murdered in her home in North Knoxville.

“Just so happens that a white woman by the name of Bertie Lindsey was murdered and her cousin who was staying with her at the time said a black man did it,” Booker said.

That cousin's name was Ora Smith. Court documents show that after she alerted a neighbor, police got to the scene.

"This policeman who hated Mays said 'I know exactly who did it', went by Mays’ house, arrested him," Booker said. "He took him out to the scene of the crime, put him under a street light and the woman who said that her cousin was murdered by a black man identified Mays as a person who did it.”

Kesler said after word spread of Mays' arrest, mobs took to the streets in an uproar looking for Mays.

"When the mob goes through downtown to raid the jailhouse and lewd and raid downtown Knoxville," she said.

Historians said the actual riot lasted about 48 hours and at one point the National Guard was called in.

But little did the mob know, Mays was no longer in Knoxville.

“The county sheriff knew that they were coming and put a wig and a dress on Mays and snuck him down to Chattanooga for safekeeping,” Booker said.

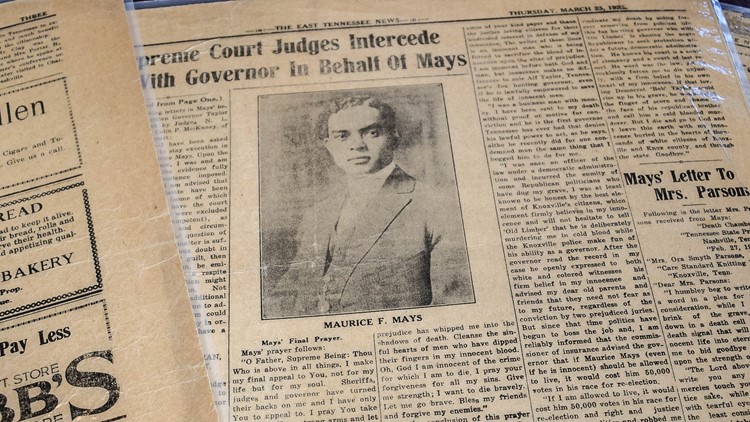

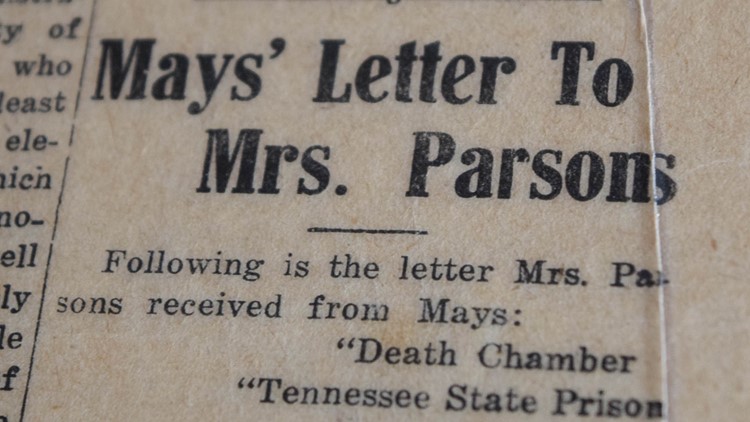

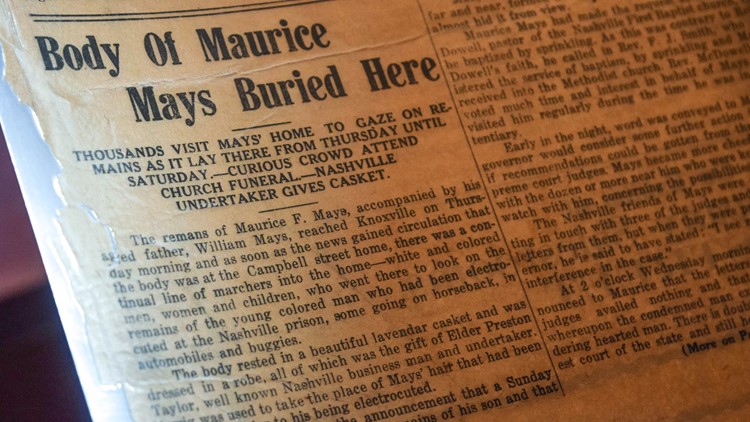

Months later, Mays was put on trial and found guilty. His case was appealed multiple times before he was executed on March 15, 1922.

“He was accused of this heinous crime and paid his life for it," Booker said.

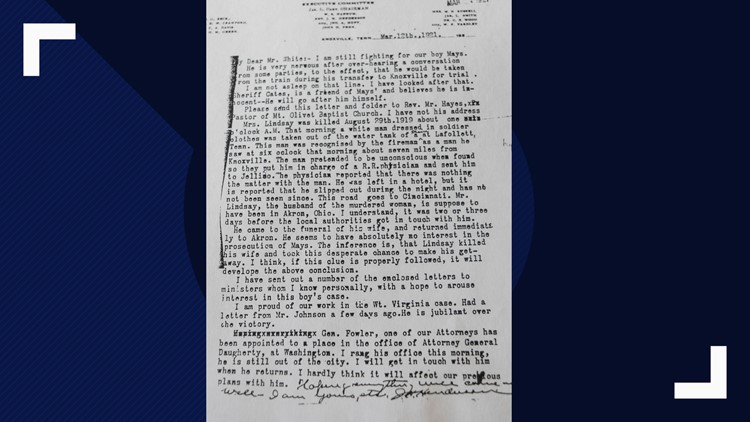

In the last 100 years, multiple local and national groups have pushed for Tennessee Governors to pardon Mays and clear his name for good.

No one has been successful.

"Did he kill and murder a white woman in the summer of 1919, there’s no evidence to suggest he did, there’s just one person who says he did," Kesler said. "Justice and equality demand that we always take a second look."

►Make it easy to keep up-to-date: Download the WBIR 10News app now and sign up for our Take 10 Lunchtime Newsletter.

Have a news tip? Email 10Listens@wbir.com, or visit our Facebook page or Twitter feed.