Note: This article was originally published March 31, 2014, and won the 2015 National Edward R. Murrow Award for best sports report.

(WBIR) Think about what you did between 6:48 a.m. Saturday and 4:38 p.m. Monday. There was plenty of college basketball with the NCAA tournament, thousands of people in Knoxville ran a marathon on Sunday, and it was back to the daily grind for many with the start of a new workweek on Monday.

Now think about what Jared Campbell of Salt Lake City did during the same span of time. He was the sole person to complete this year's Barkley Marathons in Morgan County. Campbell finished the sadistic 100-mile race up and down the steep cliffs of Frozen Head State Park in 57:50:20. To be clear, that is 57 hours, 50 minutes, and 20 seconds. The time limit for the race is 60 hours.

To fully appreciate Campbell's accomplishment, first you need to understand the ridiculous nature of the Barkley Marathons and why the nearly impossible event is known as "the race that eats its young."

"Everyone should have a chance to put themselves to the test. Especially among ultra-marathoners, a big part of the culture is testing your limits," said race founder and director Gary Cantrell. "But you haven't tested your limit until you've tried something you can't do. Then you know where your limit is. It's right there where I quit. That was it. That was the limit."

RIDICULOUS RACE'S ROOTS

Gary Cantrell, an author who writes under the pseudonym "Lazarus Lake," may seem like the most unlikely race director you'll ever meet. When you walk up to the campsite the day before the race, the bearded man in his late-50s smokes cigarettes as he checks in an exclusive group of around 40 runners chosen from sites across the globe.

"We get hundreds of applicants, believe it or not," said Cantrell. "We do not tell anyone how to enter. People have to figure out how to apply on their own. They write an essay that explains why they want to run the Barkley. This year we have runners from 10 different foreign countries. I think every continent is represented this year."

The runners brave and fortunate enough to have "Laz" allow them to compete in the Barkley Marathons will be required to travel up and down the steep cliffs of Frozen Head State Park in Morgan County. Participants have 60 hours to complete five 20-mile loops through some of the most grueling terrain in the state.

"These are just modest sized hills in East Tennessee," chuckled Cantrell. "And they're steep. And there's a lot of them. You're going straight up and straight down."

First-time runners have to pay an odd entry fee of just a couple of dollars and one of their license plates.

"These are the 'Barkley skins' we've collected," said Cantrell as he tied together a large stack of license plates to create a dangling decorative wall to hang around the campsite.

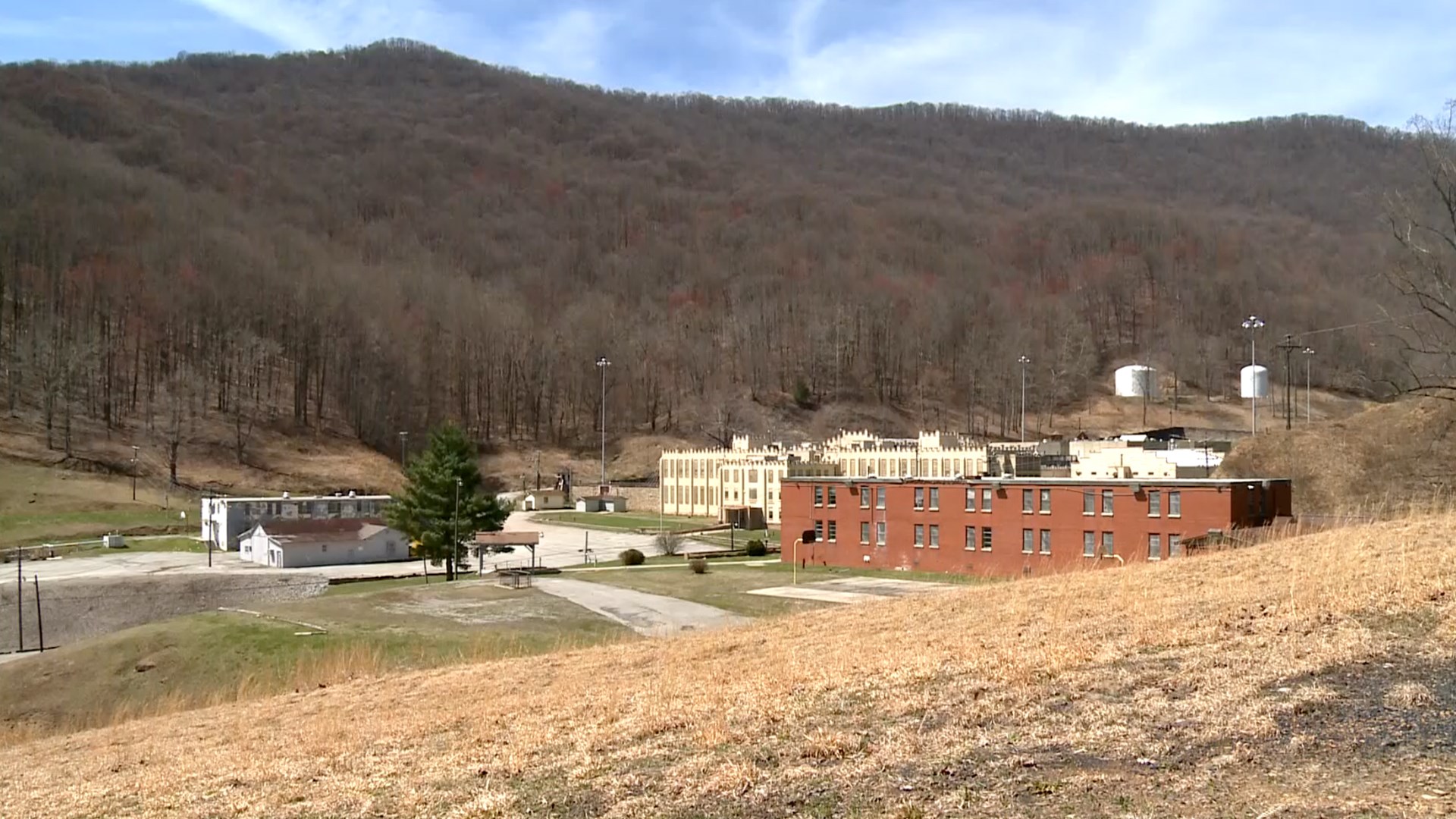

Cantrell concocted the race when he was an elite ultra-marathoner in the mid-1980s. The inspiration for the race was the 1977 jailbreak by James Earl Ray, the man who assassinated Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

James Earl Ray escaped from what is now the closed Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary at the foot of Frozen Head State Park and fled into the unforgiving hills. After running from authorities for almost three days, Ray had only traveled eight miles through the Park's torturous terrain when he was captured.

"We were laughing at him [Ray] only making 8.5 miles in 54 hours. I said in that length of time I could have gone 100 miles, because I was young and cocky. That stuck in my brain and we eventually set that out as a challenge to see if it could be done," said Cantrell.

This race that mocks James Earl Ray's futility ultimately serves a massive dose of humility to the best runners and climbers on Earth.

RANDOM RIGOR RUINS ROUTINES

Elite ultra-marathoners are notorious creatures of habit who meticulously plan when to sleep, dress, and eat before a big run.

They will find no such comforts in the hills near Wartburg, Tennessee, as they prepare for a sadistic course that takes runners through a cumulative climb of more than 60,000 feet. Prior to this year's race, only 14 people have ever completed the race within the 60 hour time limit.

Runners do not know when the race starts. They set up at the campsite in Frozen Head State Park on Friday and wait for the sound of a conch shell that signals one hour until the race begins. The conch can blow anytime between midnight and noon on Saturday.

"We have blown it as early as 2:00 a.m. and as late as noon. You have to be ready," said Cantrell.

Cantrell may not be an elite runner anymore, but he personally travels the loop when he plots the course that changes each year.

"I never send anyone some place I haven't gone. I'm an old guy with a crippled leg, so if I can do it they can do it."

As for the exact route, Cantrell jokes that each year someone sets a course record. That's because the course changes every year and is rarely on the beaten path. Runners are forced to navigate up and down cliffs through thick thorn-covered brush.

Not only does the course change every year. Runners are not given a map of the route until just before the race. Further complicating matters is the map is hand-drawn by Cantrell and hardly-to-scale, meaning it could be worthless.

"You don't know the exact course. You're out there by yourself all day and all night," said Cantrell. "After dark, what do you think route-finding is like up there at the top of the mountain in the fog? We have some special forces guys who have participated and they are really talented. They do a great job navigating."

One hour after the conch blows, runners line up at a yellow gate at the campground that serves as the start and finish of each 20 mile loop.

Cantrell does not signal the start of the race with a traditional shot from a starting gun. Rather, he casually and coolly leans against the gate, lights a cigarette, and blows a puff of smoke into the air. With that, the runners are off into the woods to meet the hills of Frozen Head State Park.

LITERARY CHECKPOINTS AND 'FUN RUN'

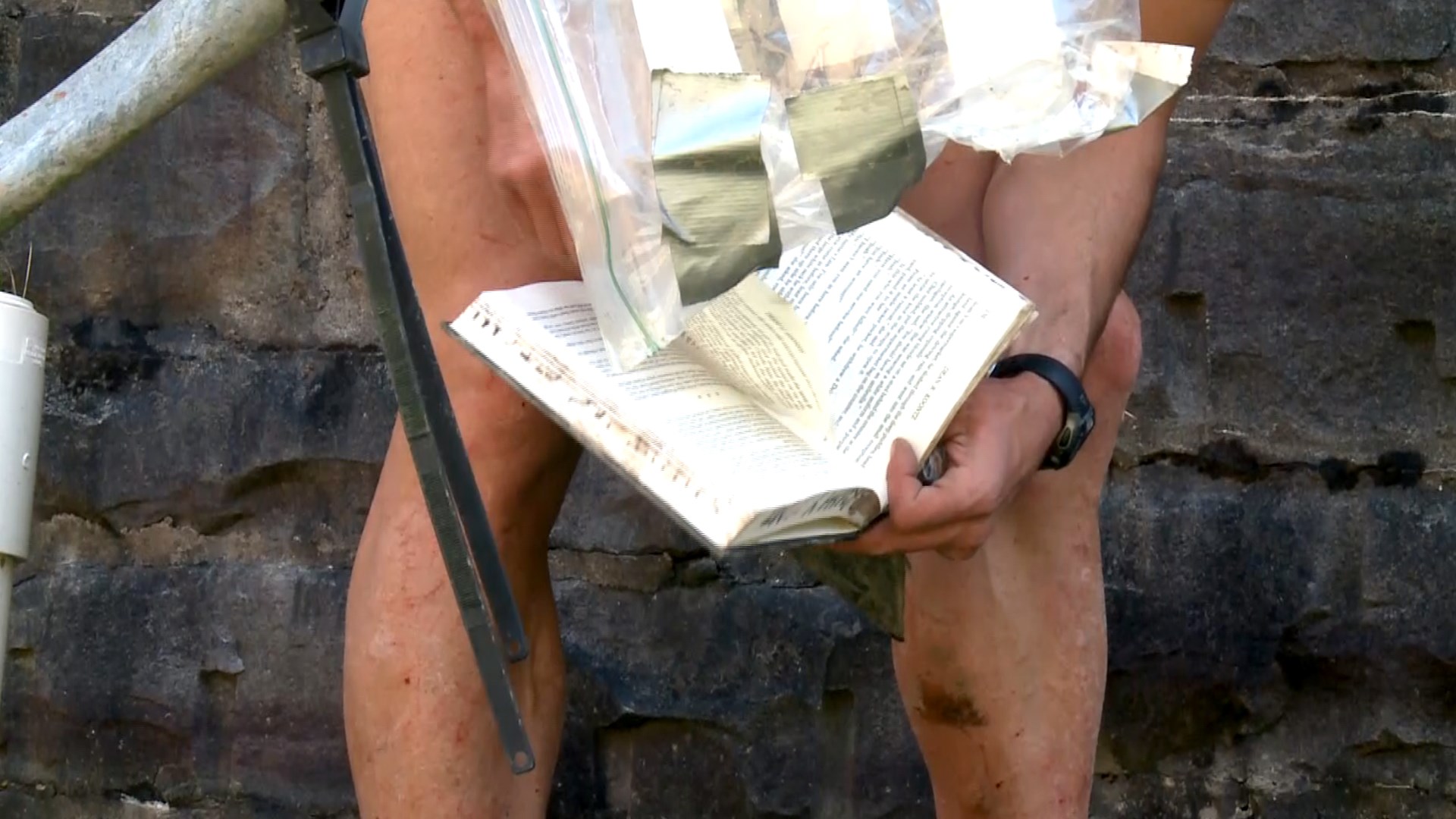

Once runners set off on their journey, a big part of the race is a hunt for 13 checkpoints in the woods to mark the loop. Those checkpoints are books in the woods protected from the elements by zip-lock plastic bags. The runners must tear a page out of the book and return with it to prove they actually ran the designated course.

"You see me giving them their numbers. They get that page number out of the book and they bring them back. If they don't have one of their pages, their loop doesn't count. It has happened before and it was tragic for the guy who lost a page," said Cantrell. "After each loop, we check the pages, make sure it counts, then give them a new number. Then they go back out for the next loop."

The only measure of any comfort is knowing one location will always be part of the loop. The now closed Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary where James Earl Ray escaped in 1977. Runners are allowed to go through a tunnel beneath the prison and emerge at the site where Ray jumped over the stone wall during his escape. This year the book placed at the Brushy Mountain checkpoint was 'The Bad Place' by Dean Koontz.

There are no water stations along the route. Runners must carry any food, water, and supplies they choose. They can also keep supplies at their tent at the campground to restock for each loop. Many runners also attempt to take naps between loops.

Many runners fail due to an inability to find the checkpoints while trying to figure out the first loop. Those who spend hours running through the woods during the initial search have wasted precious time and energy that dooms their attempts to complete four more loops.

"The time limit is not what causes most people to fail. They mentally break. You go 60 hours with no sleep, constant climbing and descending. You have to find yourself on a map. There are no pacers to find the way. You're out there by yourself all day and all night."

Runners who cannot complete all 100 miles can switch to a smaller goal. If they finish three of the 20 mile loops, they can officially say they ran the 60 mile "fun run" at the Barkley Marathons.

"The 'Fun Run' is just one more mental obstacle. It gives the runners an 'out.' One more thing that might make them decide to quit," said Cantrell. "We have some of the most incredible runners in the world here. There are guys here who have done every ultramarathon in the country. They've done 250 mile races through the Alps. They come here to test their limits."

Cantrell insists the ridiculous obstacles are not created in order to make success an impossibility. Rather, he wants the best in the world to have to perform at their maximum for the even the slightest possibility of success.

"I want them to succeed. Especially when they get on into it, you want them to succeed so bad because they've gone through so much. When someone does finish, you feel like you're elevated just by being there. It is one of the extremes of joy that can come with sports. Joy that you only get when failure was probable."

RUNNERS HUMBLED AS CAMPBELL CONQUERS

Of the more than 40 runners chosen to participate in the Barkley this year, Jared Campbell of Salt Lake City was the only person to make it more than three loops. While Campbell kept climbing his way through the thorny route, all the other runners tried to recuperate at the campsite.

The event is full of some of the world's elite runners, including champion runner Jamil Coury from Arizona who took his first crack at the Barkley. Coury made it three loops and qualified as a 'fun run' finisher of 60 miles within 40 hours. That was enough for him.

"The steepness of the slopes and the trails that we go on, it was painfully brutal. I did not expect what was out there," said Coury. "I have a 'no quit' attitude when I do events. But I was trying to come up with every excuse in the book to stop. I knew it would be difficult, but you have no idea until you actually try it."

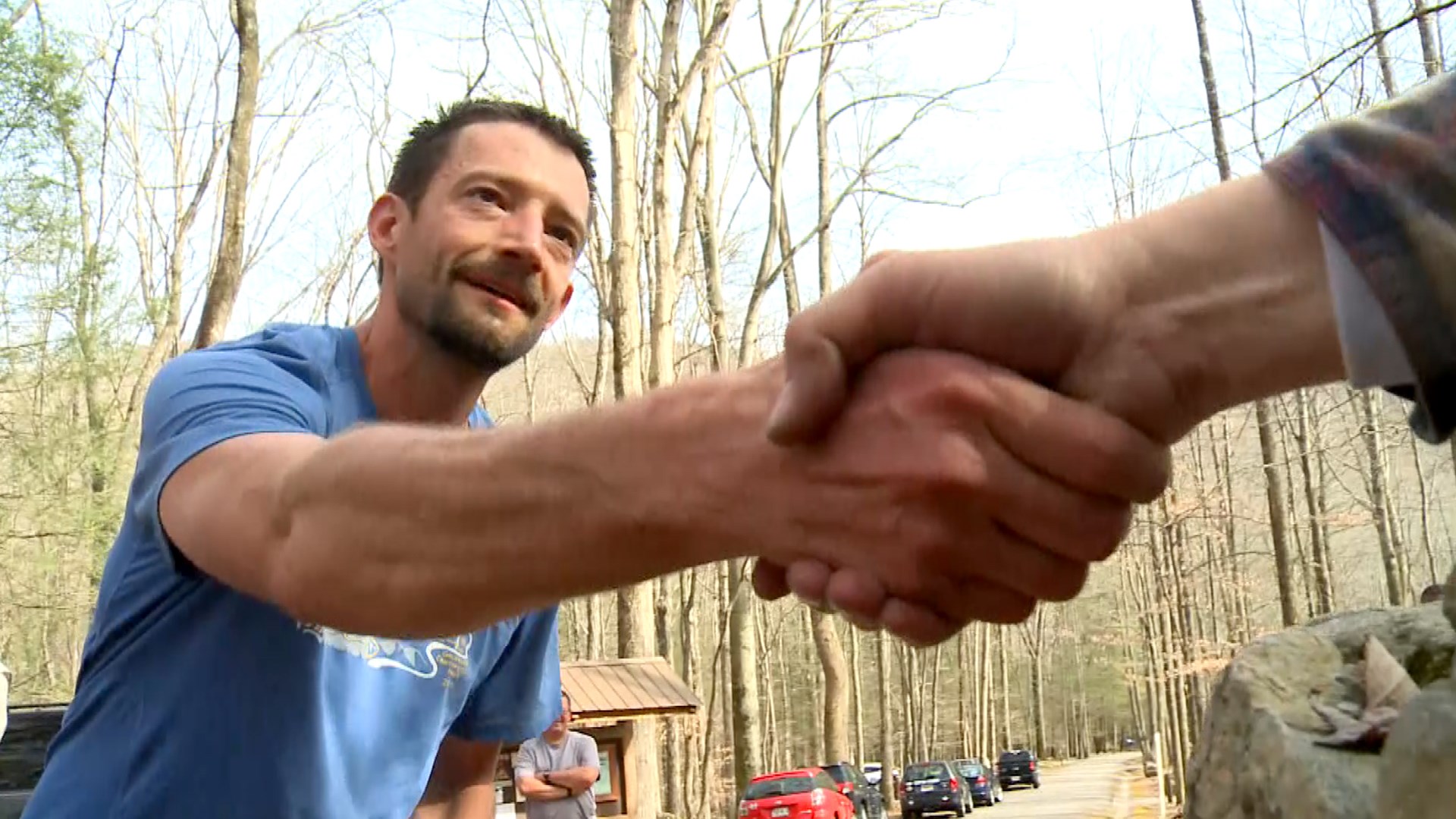

The impossible nature of the race brings unbridled joy when someone successfully conquers the course. Rousing applause greeted Campbell as he climbed towards the finish and touched the golden gate at the campsite. It marked only the 15th time the 100-mile course has been completed since the race was founded in the mid-1980s.

Campbell also became the second two-time finisher in Barkley history. He also completed the race in 2012. In all, he has attempted the Barkley Marathons three times.

"Having been out there before, it was really neat to know the streams and the terrain, even though I still got lost," laughed Campbell.

Campbell finished with a few bumps, bruises, and scars along with a lot of luck along the way.

"At one point, I literally fell head over heels 25 feet," said Campbell. "I didn't break anything. I couldn't believe it."

Other runners from around the world gathered and marveled at Campbell as he sat exhausted and answered questions from the group. An audible gasp came from Campbell's answer to a question about his training regimen.

"We go up and down Grandeur Peak in Utah. It's 3,400 feet of gain and I run it 12 times in one day. So that's about 40,000 feet in 22 to 23 hours," said Campbell. ""I end up running up and down the peaks, breaking trail and snow, so it's a lot like the slick conditions and thick forest floor here."

Campbell only took a single one-hour nap during the entire run. He said this year he also had some training with sleep deprivation.

"My wife and I, we had our first child around three months ago. So the baby definitely will teach you how to deal with no sleep," joked Campbell.

Campbell said he was cognizant of the fact he was the only person running the final 40 percent of the race. He says it served as motivation as he kept pushing towards the finish line.

"You feel like you have a little bit of a duty to finish if you're the only one out there on loop four and five. It's kind of interesting thinking about everyone here (at the campground where the race is stationed). I guess I better drag my ass to the finish line," laughed Campbell.

THE ULTIMATE PRIZE

There are no trophies or prize money for 'winning' the Barkley Marathons.

"The respect of your peers is the ultimate prize in sports," said Cantrell. "To anyone this sounds like an incredible feat. But to anyone who has actually been out there, you realize how amazing this is. It is inspiring."

There is limited mobile network coverage in Frozen Head State Park, but just enough cell service for some of the people at camp to post updates to Twitter and social media. A captive online audience from around the world kept up with the event using the #BM100 hashtag.

"All of the people who really know what it takes to do this already know he did it. The respect of your peers is the biggest prize you get," said Cantrell.

Campbell's performance definitely inspired respect after completing one of the most ridiculous races in the world.

"I mean it really is silly. But you have to get into that head space. You have to just make up your mind before that you're just going to go at all costs," said Campbell.

WORLD TAKES NOTICE

Many people in East Tennessee have never heard of this world-famous race in their own backyards. Yet, the race attracts international media who want to observe the unique race.

This year, a film crew from Paris covers the campground with cameras for an upcoming segment that will air on "Interieur Sport" in France. The race has also been covered in the New York Times, Washington Post, and by other major media outlets.

A documentary about the Barkley Marathons has already been filmed and is in production for Netflix. Filmmaker Brendan Young also profiled some of the athletes (utilizing and crediting WBIR's footage and audio) in a 22 minute film called "Barkley 100."

** Reporter's Note: This written article was originally published in separate parts on March 28, March 31, and April 1, 2014, as the Barkley Marathons progressed and concluded.