KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — East Tennessee’s roller-coaster climate featured a range of record-setting droughts and downpours in recent years.

When extreme floods or dry conditions set records, the official government rainfall data in Tennessee only goes back to 1871. In terms of how our climate changes over time, 148 years is not very much information from a scientific standpoint.

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) wants to go back a lot farther than 1871 to know its dams and water intakes can handle whatever Mother Nature throws our way.

TVA contacted the University of Tennessee's geography department to revive an abandoned project from the 1930s. The research could reveal the untold history of our climate's most extreme conditions. The data is contained in the rings of trees.

"The fact that we can understand little bits and pieces about the environmental history through tree rings, I think it is really interesting and exciting,” said Laura Smith, Ph.D. student at the University of Tennessee.

Smith’s field of study is called dendrochronology. Simply put, she looks at tree rings to figure out the age of wood, determines the years when a tree was alive, and see how the climate changed during the tree’s life.

“The trees are going to allow us to have a better idea of what happened over longer time spans,” said Smith. "Some of the samples we have in the Norris database are from trees that were alive in the 11th century."

The current project also returns to TVA’s roots in the 1930s when the efforts of a groundbreaking female scientist stalled as she encountered gender discrimination.

TREE RING SCIENCE COMES FULL-CIRCLE

Dendrochronology is not new to TVA. When TVA was formed in the early 1930s and began work on Norris Dam, it hired a leading scientist in the country to study the trees and climate history of the Norris basin.

The expert TVA hired was Dr. Florence Hawley. Hawley learned directly from the founder of the nation’s first laboratory for tree ring research, A.E. Douglass at the University of Arizona. Hawley was generally recognized as second only to Douglass in expertise and experience in the field.

"Florence Hawley was the first female dendrochronologist. She is a rock star in our field,” laughed Smith. “She took on an enormous project to establish dendrochronology as a science in the Mississippi drainage, so she was doing research throughout the Midwest and the Southeast."

TVA contracted with Hawley to lead the project to study the Norris basin. She came highly-recommended by some of the leading scientists in the country, including TVA’s lead archaeologist Major William S. Webb.

“Dr. Hawley is a young woman of unusual ability and it is my firm conviction the one person best trained in the whole of America, or for that matter in the world, to do a study of rainfall in the Norris Basin,” wrote Webb in 1934.

Hawley’s valuable research stalled at TVA and never met its full potential for many reasons. One factor was impatience with a slow scientific process. Another was discrimination against women.

"There were certainly gender discrimination issues with her being a female scientist in the 1930s. And because it was the 1930s, it is pretty blatant at times in the documents,” said Smith. “There is an exchange where one manager says they should just hire an engineer, a man, and train them to do Hawley’s job.”

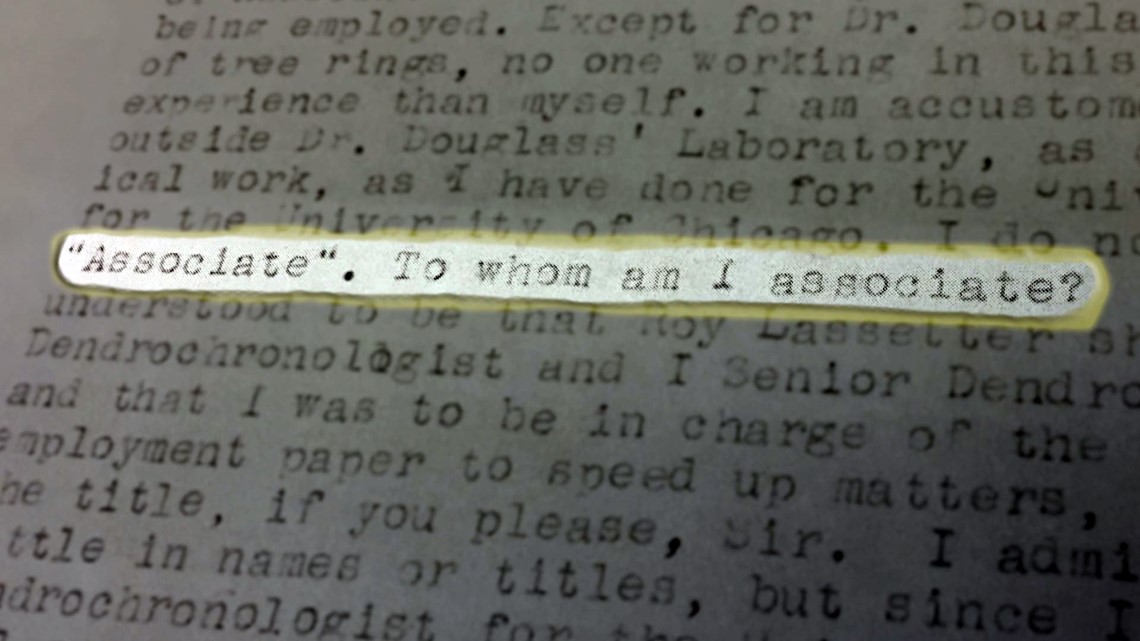

In a letter to TVA dated Oct. 15, 1934, Hawley objected to TVA assigning her the unexpected title of “associate dendrochronologist” despite her role as top scientist for the project.

“To whom am I associate? The arrangement was understood to be that Roy Lassetter should be Junior Dendrochronologist and I Senior Dendrochronologist for the TVA and that I was to be in charge of the work,” wrote Hawley.

As the project advanced, so did Hawley's academic career. She returned to the University of New Mexico where she was hired as a professor of archaeology and anthropology. Her research for TVA was primarily conducted between semesters. After years of work, Hawley was never allowed to publish the results of her red cedar study and she abandoned the project in the 1940s.

A couple of years ago, TVA lead hydrologist Curt Jawdy came across Hawley’s abandoned project. Jawdy contacted the University of Tennessee and Smith about renewing the research.

Smith said she is happy for anyone to resume Hawley’s efforts. Yet, she takes additional pride as a female scientist.

"I do. I feel like I have a lot of emotional investment in this project. I want to do right by her legacy,” said Smith. "It's important for young girls and young women to see other women going out there and doing the work."

DRAWING COMPARISONS

The tools and techniques have advanced since Hawley began collecting samples in the 1930s. The science itself is fundamentally the same.

“To put it simply, each ring is one year. The thicker the ring, the more water was available to the tree when it was growing during that particular spring and summer. A narrow ring means there was a drought,” said Smith.

Smith collects samples from old eastern red cedars by drilling to the center of the trees and extracting core samples that are about as thick as a drinking straw.

“The first question I get is whether it kills the tree. It does not. These trees are well-adapted to dealing with things like insects or birds that bore holes in them. This technique lets us see the rings of a tree without having to cut it down,” said Smith.

Smith uses eastern red cedars because the species can live hundreds of years and the wood often remains well-preserved long after the tree has died.

It’s one thing to know how many years a tree lived. It takes another step to figure out exactly when it was alive.

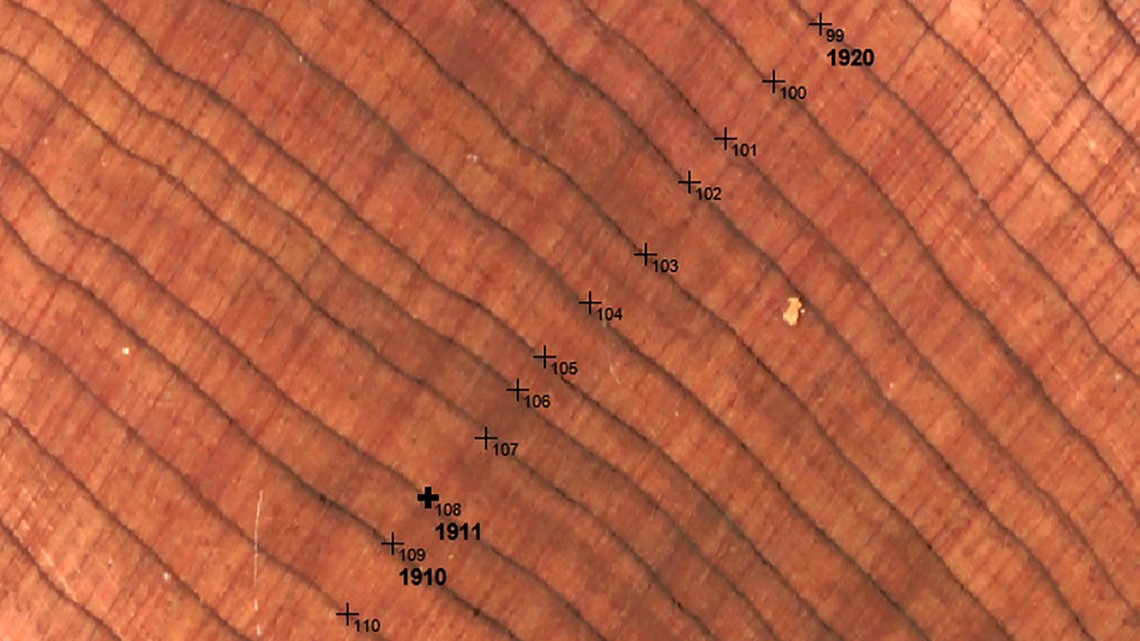

“Some of the stumps we find have been dead on the landscape for potentially millennia. We don’t know how long ago they died. So, we can measure their rings and then do a cross-comparison with our data from other trees we’ve already dated. The rings will line up to a specific year,” said Smith.

Getting the tree rings to line up with a specific moment in time often relies on distinct patterns from “marker years.” Those years are when harsh conditions impacted all the trees in the region.

“One of the marker-years is 1774 because it has a frost ring. That’s a darkened scar caused by a hard freeze that spring. That freeze in 1774 happened after two straight years of drought, so you have a distinct pattern of two very narrow rings beside a dark frost ring,” said Smith.

EXTREME EXPLORATION

Smith’s research specifically looks at years with extreme droughts. If Smith knows what a typical tree ring looks like from the worst droughts of the last 100 years, she can compare them to the most narrow rings going back almost a thousand years.

By comparing the thickness of the rings, the research can determine if the droughts centuries ago were significantly drier than anything we’ve experienced in recent generations.

TVA wants the research for a practical purpose. The utility believes its current setup for water supplies can handle a historically worst-case scenario. Smith’s research could prove it correct or reveal TVA should consider making changes.

The research could not only prove TVA’s longtime boast that it has one of the most stable water supplies in the nation. It could quantify how much better its system is than other parts of the country. This could boost the local economy by helping recruit industries that can be confident they will not run out of water.

“I think understanding historic climate and how that may impact us in the future is something that affects everyone,” said Smith.

HELP HUNT FOR CEDARS

There is still a lot of work to be done collecting and examining core samples before the results of the research are in. TVA wants your help finding eastern red cedar trees for samples at its public lands and recreation sites.

You can help with the hunt by installing the free iNaturalist app on your smartphone. The app allows you to take pictures of trees and mark their exact GPS coordinates.

When you install the app, search for the project named TVA Cedar Seekers.

The app shows you how to identify red cedars. The researchers are especially looking for old twisted cedars found along river bluffs and rock outcrops.

TVA prefers trees on its lands, trails, and campgrounds near Norris Lake, Nickajack Lake, Kentucky Lake, and Fontana Lake. However, it welcomes observations anywhere in Anderson, Benton, Marion, Perry, Henry, and Decatur counties in Tennessee, and Swain and Graham Counties in North Carolina.