KNOXVILLE, Tennessee — Once in a generation, maybe, a city gets a chance to transform itself.

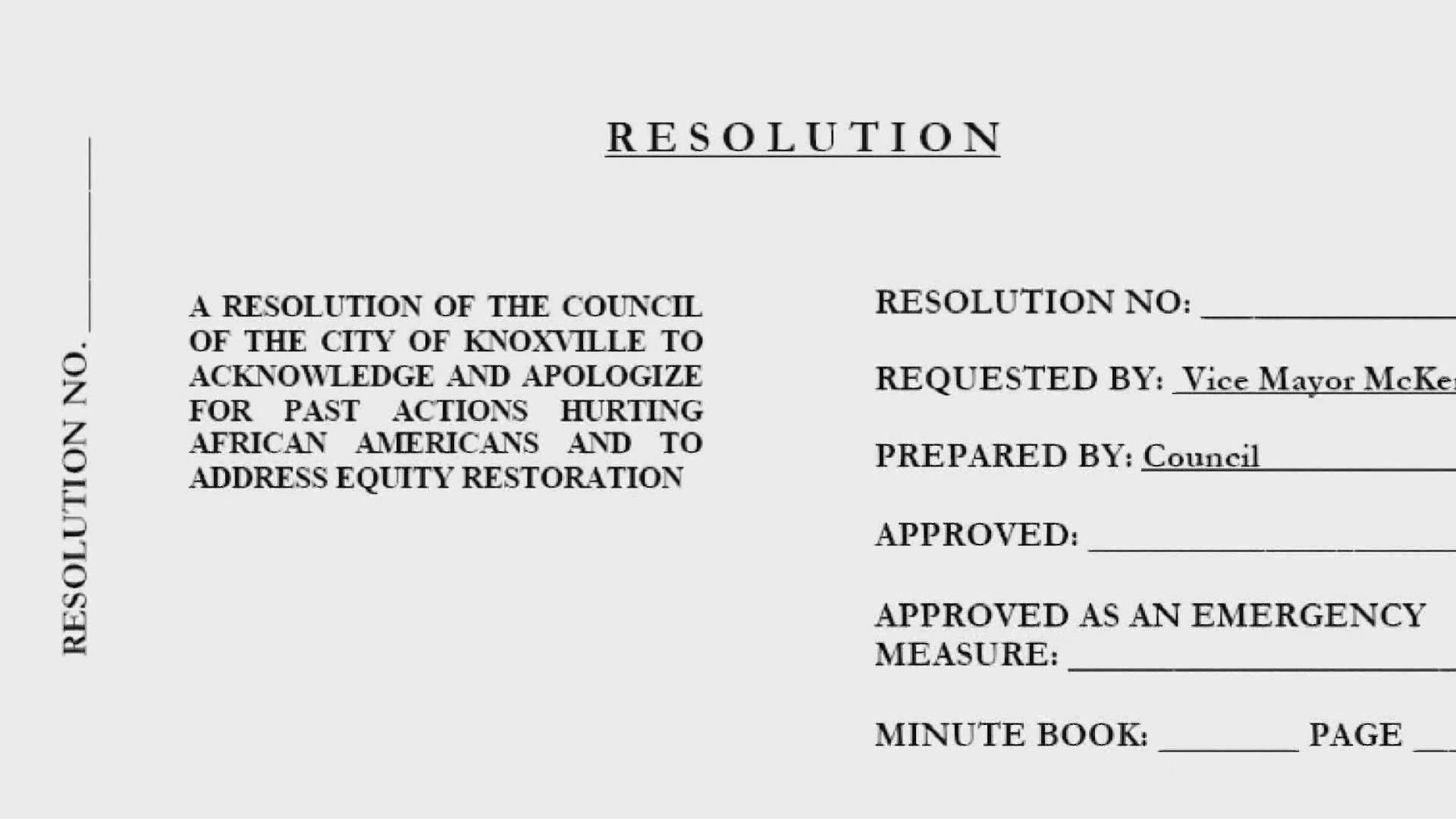

The 1960s saw dozens of Black families and businesses forced out of neighborhoods east of downtown to make way for a trafficway and a civic and government complex. Survivors still bemoan the damage wrought by mass evictions.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Butcher brothers pushed development of an old rail and industrial yard west of downtown for the 1982 World's Fair. The site floundered for years afterward but the grounds below the watchful eye of the Sunsphere today are a draw for visitors, city-dwellers, runners, bikers, sunbathers and -- when the virus subsides -- live music fans.

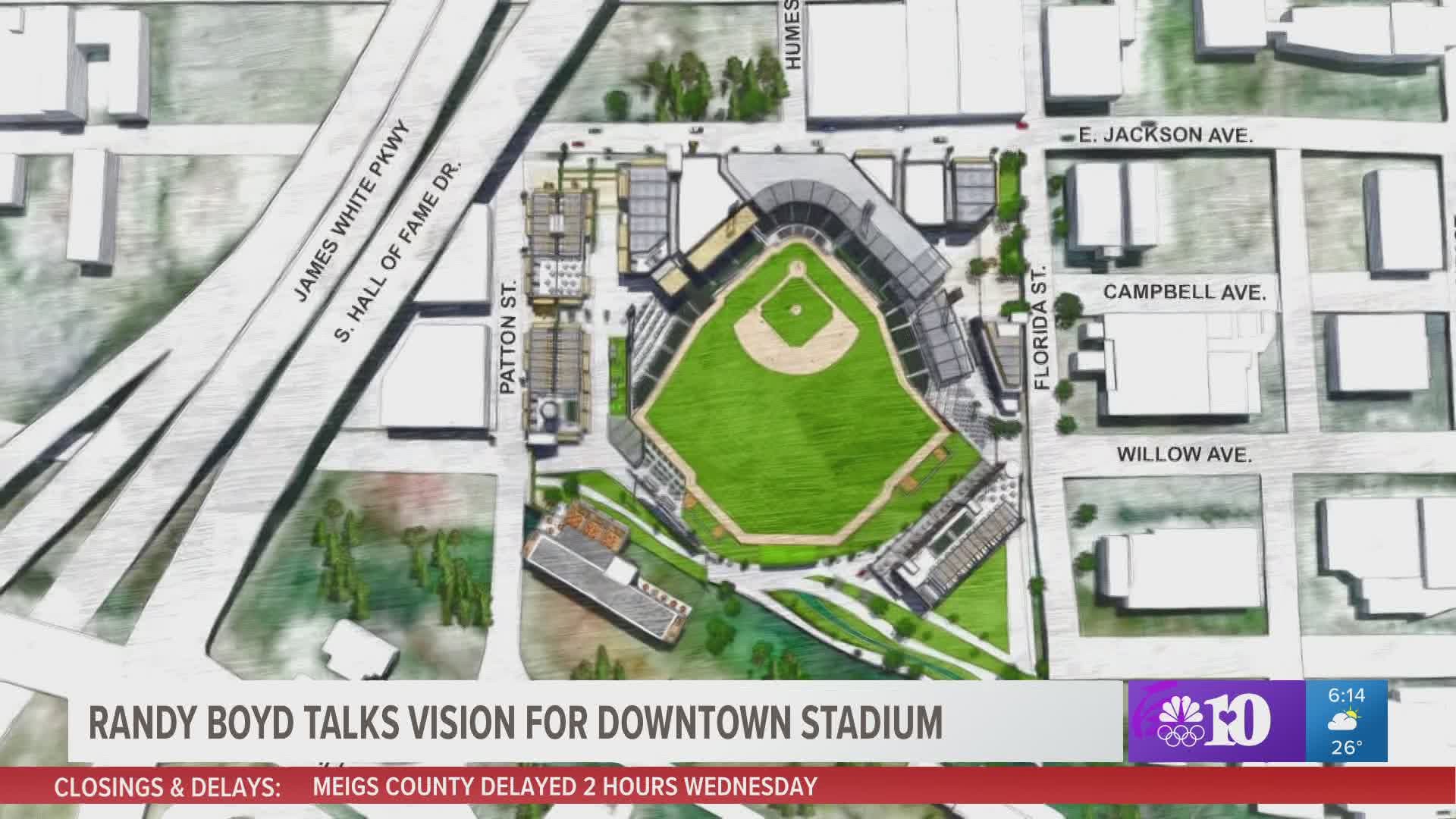

Now developer and South Knoxville native Randy Boyd is touting the transformational benefits of a sports park just east of the Old City.

Boyd thinks it will revitalize the blighted area, triggering new development and creating new life on the western edge of East Knoxville.

"I've had a love for baseball for decades. One of the things I have loved about it is how it brings communities together," said Boyd, owner of the Tennessee Smokies baseball team among others.

The most successful baseball teams are the ones that operate in a downtown, he said.

"They bring people from all parts of the community together. They share local foods and local cultures, and it's just a great community-building event."

City and county leaders like what it would offer, even as they express caution about all the obstacles that must be overcome for it to become a reality.

There's the cost and financing. The planning. The infrastructure. The construction. The community skepticism.

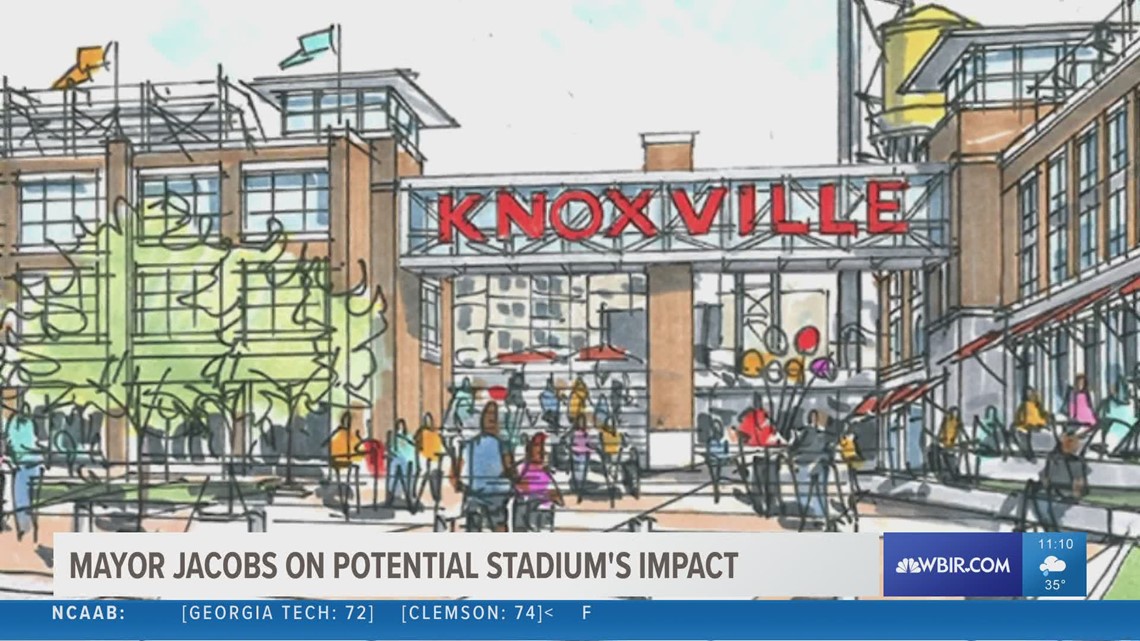

At first a skeptic, Knox County Mayor Glenn Jacobs is now a supporter.

"If this were just a baseball stadium that we were building out in the middle of nowhere and surrounding with a parking lot and that was it and we were just handing the deed over, that would be one thing," he told 10News.

"This is part of a comprehensive economic development. In addition, it is a multipurpose facility. It really helps the civic furniture here in Knox County."

Mayor Indya Kincannon sees many potential community benefits to the project.

"What I can envision here in a few years is a municipal stadium that is the home to the Knoxville Smokies baseball but also is a place where people can come and walk and can have festivals and concerts and be a venue for other sports," she said.

DETAILS

Boyd has been quietly preparing for a stadium near Knoxville's Old City for months. He's bought up land at and around the old Lay's packing plant between Jackson and Willow avenues below the James White Parkway for the site, plus he's been recruiting backers for another $140 million in private development.

Boyd would give the land for the stadium to the public. That part of the project would be overseen by a sports authority, featuring city- and county-appointed members.

The stadium has an estimated cost of about $65 million. The city and county also anticipate additional infrastructure costs once crews starting digging around in the dirt.

The sports authority would issue bonds -- creating debt -- with a 25- to 30-year life to pay for the stadium.

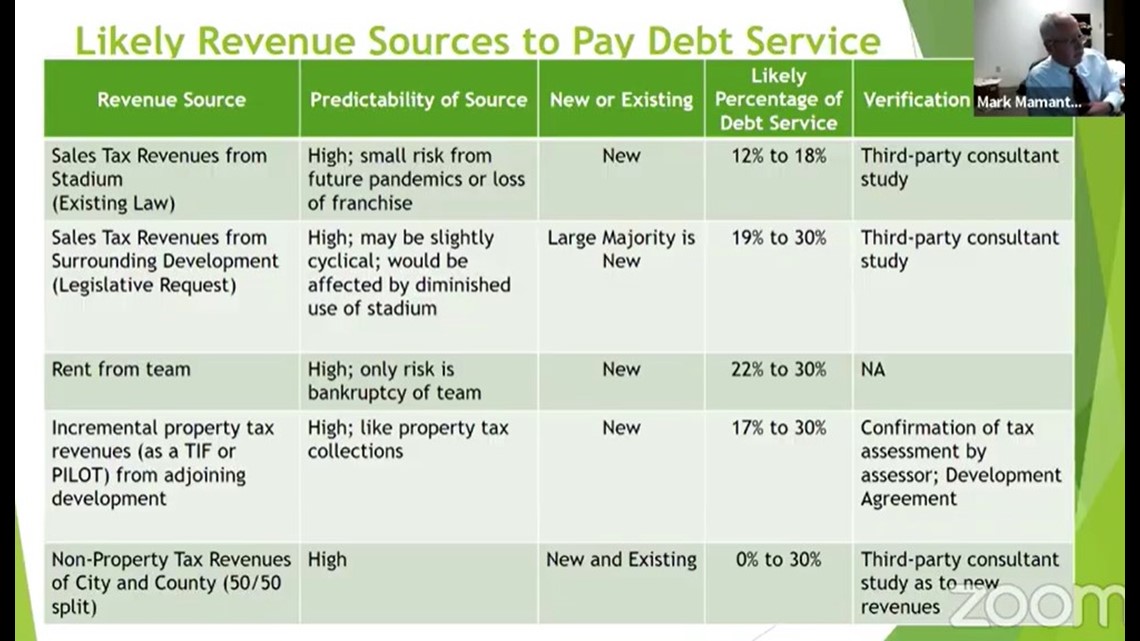

Deputy Knoxville Mayor Stephanie Welch and Knox County Finance Director Chris Caldwell said a variety of sources would be used to cover the project costs including sales tax generated from stadium concessions sales, sales tax from sales in a defined area around the stadium and "significant" team rent. Tax-increment financing or a PILOT also are envisioned to help cover costs.

Property tax rates would not be raised to pay for the complex.

Staff concedes there's the chance the project could run into money problems. Sales tax receipts, for example, could fall below expectations.

Across the U.S. in 2020, for example, the onset of the pandemic halted or sharply cut into public use of sports facilities. Something like that would hurt stadium funding.

Welch, however, said she didn't think any potential shortfall would exceed monies on hand that could cover it.

"Worse comes to worst and it's a complete failure -- that's not good. But we're trying to protect that as much as we possibly can," Jacobs said.

Last week, state Sen. Becky Duncan Massey introduced legislation that would allow a share of state sales tax collected from an area around the stadium to be used to help cover costs.

Boyd's Double A Tennessee Smokies would play 70 home games at the stadium, bringing in potential revenue for surrounding businesses. It could also be used to host events other than ball games, officials said. Boyd said that he hopes the stadium could host around 350 events per year.

QUESTIONS

Some council members and community leaders have raised concerns about the stadium.

County Commissioner Charles Busler has asked about parking. As proposed the current project doesn't include a parking garage.

Welch and Caldwell say hundreds of parking spaces already exist within a quarter to a half-mile of the site. The idea is for users to plan an outing around the stadium site, making stops perhaps at a restaurant or bar.

A developer-commissioned study found there are 1,333 existing parking spaces within a quarter-mile radius of the stadium site, 7,675 within a half-mile radius and 15,730 within a one-mile radius

Parking questions may persist from motorists prefer easy in-out access.

At-large City Councilwoman Amelia Parker asked numerous questions of Welch, Caldwell and bond counsel Mark Mamantov on Feb. 4 during a Zoom workshop about the project. It was the first time Council and Commission got together to talk about it.

Parker raised the question of private financing for the stadium. Boyd said he and his investors can't afford to pay for that. He said being in Sevier County as the team is now also is a perfectly fine business arrangement.

Parker also wondered about Boyd's commitment going forward to keep the team. What if he runs into "financial challenges" that force him to sell?

Boyd, 61, said that's not going to happen.

"We have the resources to continue to support this team as long as we live," he said.

She also wondered why Boyd hadn't donated the land to a Black non-profit if he wanted to help counter the community's high-poverty rate. Boyd said he thinks the overall economic impact of the project will help everyone, including disadvantaged people in East Knoxville.

"If the city and county -- and you have a vote in this -- decide that this isn't a good use of the land then I'll go back and re-think what I do with this land," Boyd said.

Commissioner Randy Smith inquired about annual operating expenses and long-term upkeep expenses.

Mamantov said the team would be responsible of operating expenses but negotiations still must occur to address long-term capital expenses as the stadium ages.

The lawyer, responding to Smith, also said a consultant would be hired to backstop Boyd's estimated costs and economic impact estimates. Mamantov said he hopes by the end of March to get an independent financial assessment of the project.

Hours before the county-city workshop, 11 area groups sent an open letter to government leaders and Boyd about the project.

They argued more time should be devoted to public discussion and debate. They also want the new sports authority to include some of their members.

"We request transparency and public accountability during the negotiations of this proposed project. Our respective memberships, which include a wide variety of individuals with many unique interests and skills, represent many voices concerned about the public interests in this project," the letter states.

"Our inclusion will allow this discussion to occur in a way that protects the various stakeholders and their respective interests. Our input is vital to the success of any proposed baseball stadium."

Signatories included Alliance House Community Coalition, the City Council Movement, Jobs with Justice – East Tennessee, the Knox Liberty Organization, Statewide Organizing for Community eMpowerment (SOCM) and the United Campus Workers, UTK Chapter.

Parker requested additional workshops as well. City and county leaders said during the Feb. 4 workshop that future briefings can be held.

WHAT'S NEXT

Boyd told government officials earlier this month that if he just wanted to make money, "we'd stay where we're at."

He views the project as part of his legacy, something that will expand the tax base, create jobs and give people in East Knoxville a shot at a better life.

Kincannon told 10News the stadium can be one "catalyst" among many that makes Knoxville better. The stadium site gets little use right now, she said.

Besides offering multiple uses, the new development can trigger partnerships with area schools and offer apprenticeships that lead to career skills, she said.

"It's all part of a collective effort to invest in the people of this community," she said.

Jacobs worries there's not enough in Knox County to keep younger, upwardly mobile people around, people in their mid 20s to early 50s. They're leaving because they want more things to do and see better opportunities elsewhere, he said.

Big employers, when they think about relocating, look at how appealing a prospective city will be to the workforce.

"We've actually lost younger folks," Jacobs said. "They're the ones that are in the prime of their careers. We can't afford to have that happen."

The stadium and its accompanying development offer appealing amenities, he said.

Boyd, who has a reputation for wanting to get things done yesterday if not sooner, said he hopes construction on the residential and commercial part of the $140 million private development can occur simultaneously to stadium construction.

A potential timeline has stadium construction starting in the fall and continuing through early 2023 in time for Boyd's baseball team to take the field in April 2023.

As everyone agrees, it's a very tight schedule.

"My goal is for all of it to be built at the same time," Boyd told city and county leaders.