KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — Editor's Note: WBIR is reporting this week on the evolution of the University of Tennessee's Body Farm. This is the fourth installment.

Look beyond the queasy nature of the place and you'll discover there's a rich amount of science conducted at the Body Farm.

Facial recognition studies, chemical emissions of a corpse post-mortem, fire's effect on bones, how light detection technology can discover long-lost graves.

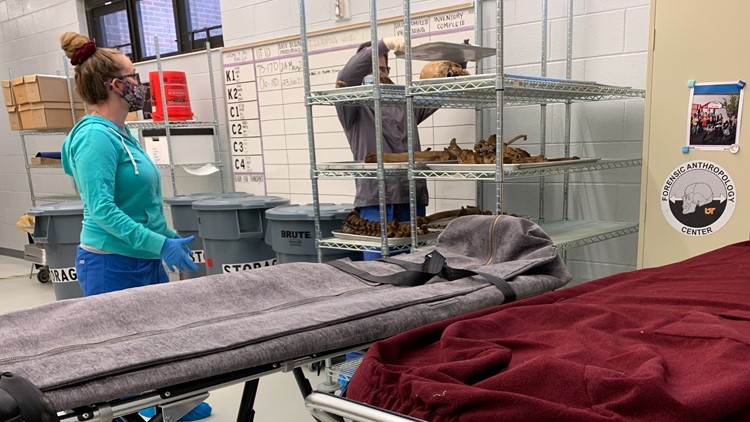

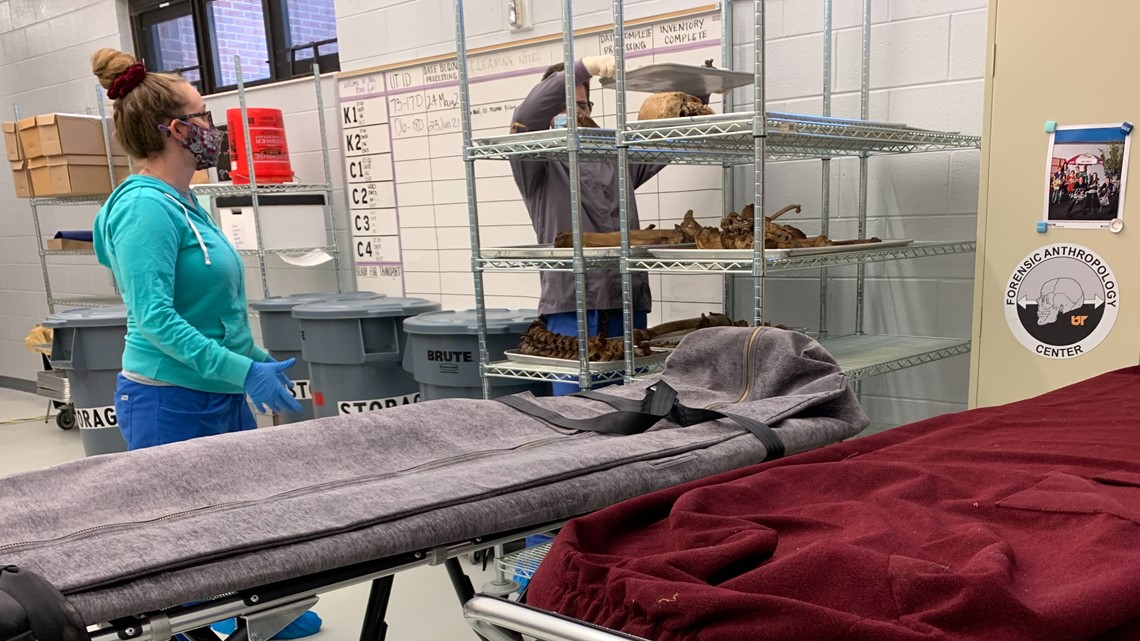

Dr. Dawnie Steadman, who heads the University of Tennessee's Forensic Anthropology Center, which includes the Body Farm, said while the anthropologists who work there maybe aren't crazy about the pop culture depictions of what they do, the hype does get the public's attention and present an opportunity to educate people about the actual science going on there.

"The research we do helps people, and that brings a sense of community and pride to what we do, and I think that that's really important," Steadman said.

FIRES AND FACES

The possibilities are limitless for experiments with bodies and bones.

Past research by forensic anthropologist Arpad Vass has looked at what chemical compounds are emitted over time by a corpse.

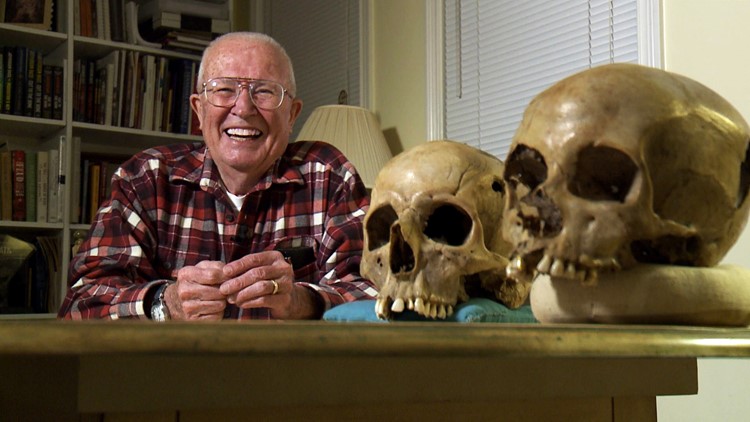

Dr. Bill Bass, the founder of the Body Farm, recalls a time when Vass had several bodies buried at once, with pipes leading up to the surface so that readings of the chemical emissions could be made. The research was supposed to go on for several years but was extended much longer in time, he said.

Vass's work has practical uses: Even if a body is no longer present, are there key chemical markers or signatures that may be left behind -- that can show the presence of a dead person? Vass argues that the answer is yes.

He would end up testifying about his research in 2011 at the ballyhooed Central Florida trial of Casey Anthony, accused of murdering her toddler daughter. Prosecutors sought to show that Anthony's car contained chemical compounds consistent with those given off by a dead body.

FAC Associate Directors Giovanna Vidoli and Joanne Devlin are conducting an ongoing project that looks at how fire affects bones.

It's an area that hasn't been deeply explored. We know fire can do awful things to bodies, but how do you differentiate skeletal injuries to a body that happened before death, perhaps because of an assault, and trauma inflicted by the flames and heat themselves?

For this work, they're deliberately breaking the bones of a corpse and then subjecting them to fire and comparing those effects with bodies with no trauma at all.

The forensic center advises and gets permission ahead of time from donors or their families that a body could be subjected to trauma as part of the research, said FAC Associate Director Lee Jantz Meadows. Over 80 percent consent, she said.

"That's going to be a game-changer with how we interpret fire deaths, and give us so many better tools to understand what the difference is between trauma that happens to a body before the fire and after the fire," Steadman said.

Hayden McKee-Zech, a doctoral student in UT's Anthropology Department, is studying how hungry scavengers, such as insects, affect a body's decomposition and how scavengers react to medications that a human may have in him or her.

For years the FAC has looked at the external factors that can affect decomposition such as temperature and season.

It turns out the drugs a person has in their system at death change how scavengers develop, which means entomologists must alter their estimates of time since death to factor in the chemical influence inside a body, Steadman said.

"It really does affect the entire decomposition process and everything we use to help identify people or time since death," Steadman said.

Amy Mundorff, assistant professor of anthropology at UT, has tested a technology called LIDAR on corpses buried at the Body Farm. It measures the distance of light beams between objects and can be used to define objects and shapes underground.

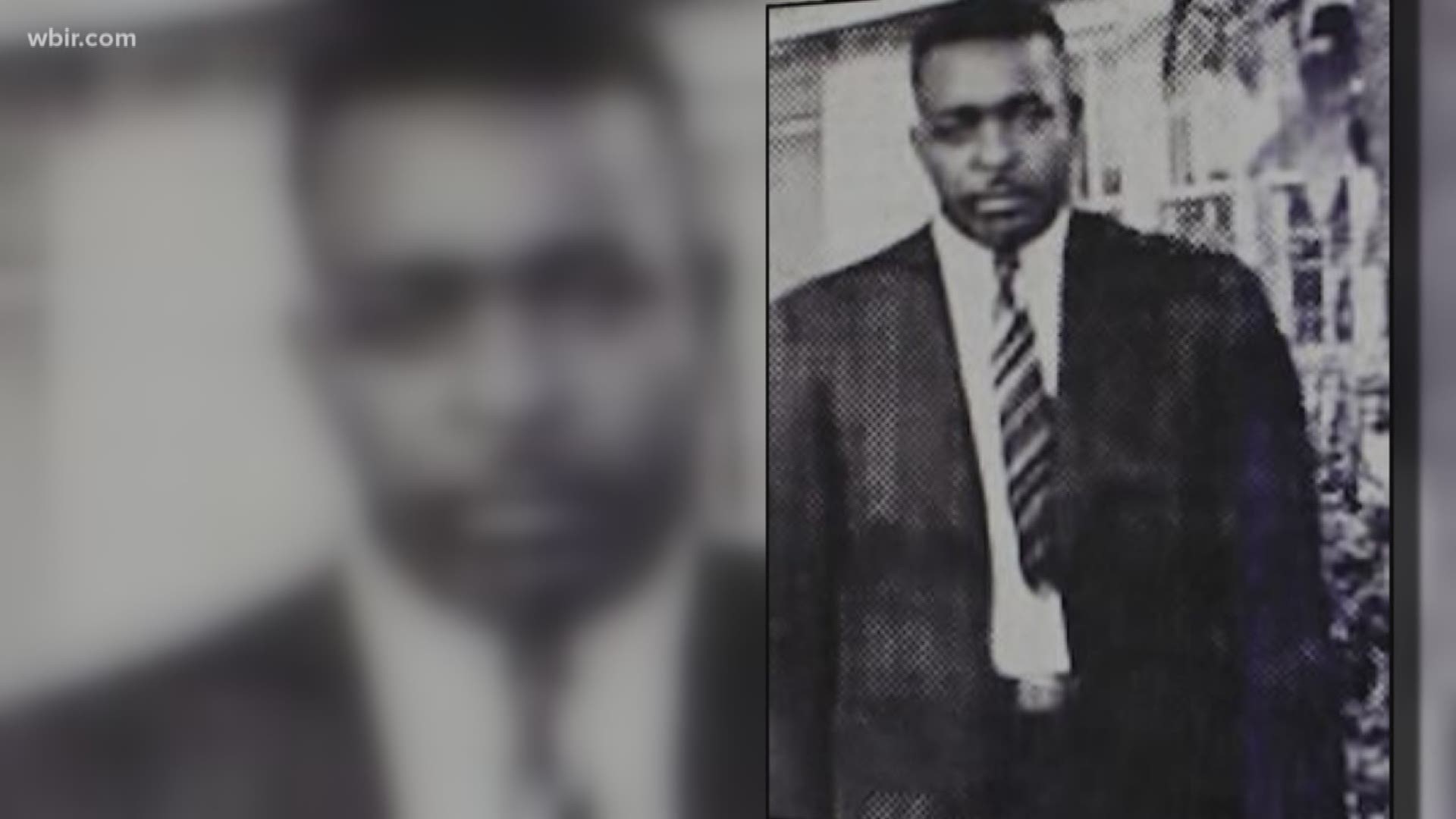

Mundorff found that LIDAR could be used to detect bodies in a mass grave. She's now going to use the technology to find a Black man, Elbert Williams, who was abducted and later found dead in 1940 in a West Tennessee river. He'd been one of the founders of a local NAACP chapter.

He was hastily buried in an unmarked grave. The NAACP announced several years ago efforts to find his remains to look further into his death. Mundorff has said she'd use her experience with LIDAR to help in the search.

Other research has looked at how exposure to water affects bodies and what happens to them if they're left in a car. (The car remains today at the Body Farm.)

Other ongoing research is looking at biometric markers -- such as the face and fingerprints -- and how they can be used to identity people after they die. Living "pre-donors" are taking part in the research, with images being recorded of them in life for later comparison in death.

It's one of the FAC's oldest current projects, dating to 2014, according to UT.

What goes on at the Body Farm

Another study is looking at how decaying material from a human body can affect the coloration of nearby trees -- perhaps offering a physical sign of the presence of a dead person. If leaking material from a body changes the leaf pattern, that could be a telltale sign for searchers trying to find a missing person.

Vidoli said there's no end to the kinds of research the Body Farm and the FAC can accommodate.

"I don't think we are ever maxed out," she said. "I think that as our abilities grow and as our knowledge also grows and technology changes, we will always be able to increase and improve what we can do," she said. "I think that's the beauty of any forensic science. It's not stagnant."