KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — The way Lucinda Denton sees it, when you're dead, you're dead.

So why leave your remains to rot in the ground when they could serve science? She's never liked tombstones anyway.

The 84-year-old West Knox County resident signed the papers years ago to donate her body to the University of Tennessee's Anthropology Research Facility, better known as the Body Farm.

"The idea of being buried -- that's the end. But if you go to the Body Farm, you're useful -- you're useful for research!" the Rocky Mount, N.C., native, mother of three and grandmother of seven said.

Her family understands her wishes. Her late husband, Harold, understood her wishes, although he wasn't interested himself in going out to the three-acre grounds near the University of Tennessee Medical Center.

Some day, hopefully while she's at her wooded home by Fort Loudoun Lake, she'll pass in peace, she said. Then, it'll be time to come get Lucinda and take her to the Body Farm.

Who knows? Maybe the former schoolteacher will be wearing the Body Farm T-shirt her son gave her as a birthday present several years ago.

WHEN THE RED PHONE RINGS

Forensic Anthropology Center administrators at UT say it over and over: They can't pursue science without donors' bodies. They are forever grateful for the people who decide to donate their remains.

"We have the utmost respect for our donors," said FAC research associate Mary Davis.

Some at the center have even made the decision to donate themselves, including Davis and veteran Associate Director Lee Meadows Jantz.

"I do plan on donating," Davis said. "I strongly believe in the work we are doing, and I know firsthand we can't do this work without our donors, so I plan on continuing this work even after I die."

Would-be donors must go through an application process.

Hundreds have done it over the last 40 years. More than 5,000 people are "pre-donors," meaning they've been screened and are in the system, according to FAC Director Dawnie Steadman.

You can find more information about donating your body here. They can't take everyone who wants to donate. No one who is HIV-positive or has had tuberculosis, for example, will be accepted.

They also can't accept people who have been embalmed.

Once you're accepted into the program, you'll get a donor card to keep in your wallet or among your personal papers, Davis said.

While most people who come into the program have made arrangements long before death, sometimes donations come abruptly. There've been instances, for example, when the family decided at death that they wanted a member's remains handed off quickly.

What goes on at the Body Farm

It's possible that as part of the research, a person's body will be subjected to trauma. In the name of science, their bones could be broken. Donors and families are advised about that in advance in case they have objections.

It's wise for donors and families to have talk about a donor's wishes, Steadman said.

"Not everyone in the family may understand or agree with it, but as long as they know those are your wishes and why, they may be more likely to follow through," she said.

Many people who plan to donate are already enrolled in a research program.

Denton, for example, is taking part in long-term biometrics research for the military that involves facial recognition and how well a face can be recognized during decomposition. Her face has been photographed in life; it'll also be photographed in death.

The Body Farm doesn't come pick up your remains from your house or nursing home. But someone from the center will drive anywhere in Tennessee within 100 miles to retrieve your body and bring it back to Knoxville if, for example, it's at a hospital, medical examiner's office or funeral home.

The FAC has a special phone, carried by someone all the time, that's dubbed the Red Phone. Steadman is among those responsible for answering it.

It's a phone that families can call with questions about the donor program. And it's the phone that a funeral home or police will call when it's time to pick up a body.

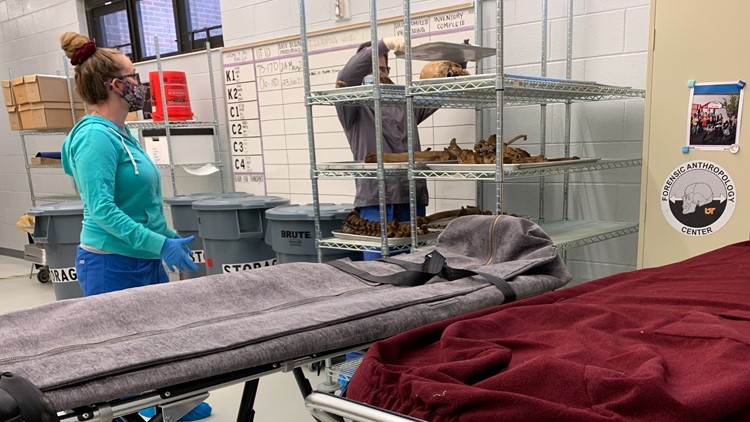

Donors are taken to an intake center at the William M. Bass Forensic Anthropology Building, named after Body Farm founder Bill Bass, where they're catalogued and tagged. Most eventually will end up at the nearby Body Farm. They may be buried, put on the ground under a cover of black sheeting or left in the open.

Students and researchers will study them maybe for a year or two, investigating everything from decomposition rate to the impact scavengers such as raccoons and vultures have on decay rates.

At any given time there are 150 to 200 bodies out at the center, Steadman said.

THE COLLECTION

When a research project ends, a donor's remains go back to the Bass building. This time they'll be scrubbed, picked and cleaned by students. If necessary, the lab has crockpots for boiling away small bits of mummified tissue and cartilage.

The lab works to ensure every single one of your 206 bones comes back to the intake center.

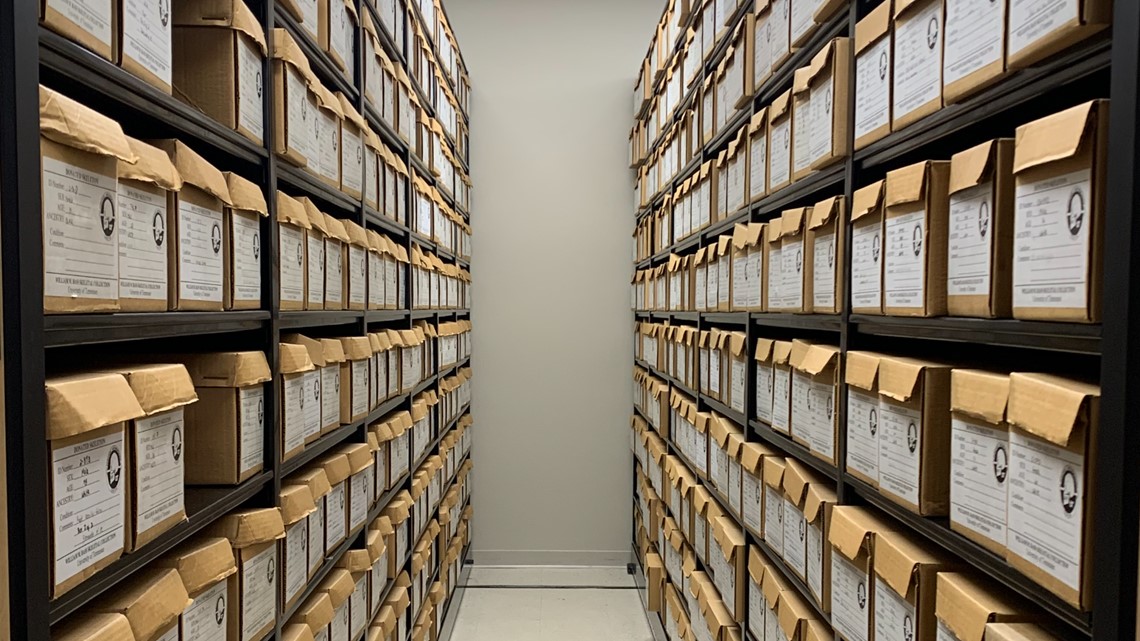

After they've all been cleaned, they're numbered and prepared to be boxed and housed in the Bass Donated Skeletal Collection housed at Strong Hall on the UT campus.

Every donor's box includes their catalogue number, sex and age.

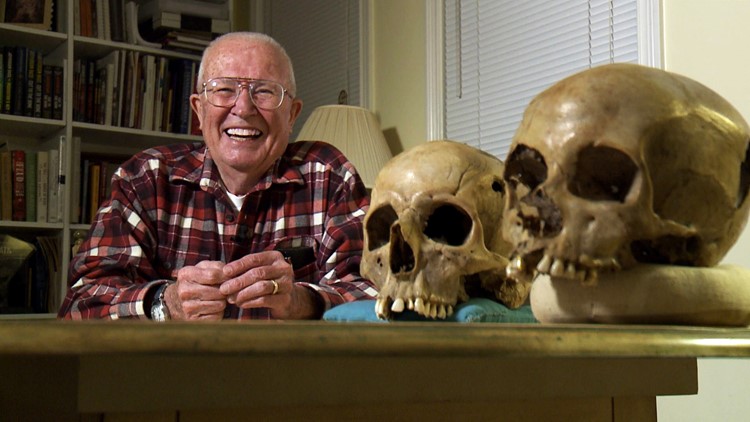

More than 1,800 people are in the skeleton collection, the oldest of whom was born in 1892. Bass started the collection in conjunction with the creation of the Body Farm in 1981.

Even though a donor goes on a giant shelf among giant rows of boxed bones at Strong, their educational contributions continue. Your bones could still be used for further study.

If they want, family members can arrange to come visit a loved one's bones. Staff will also talk over with them the kind of research that's been conducted with the remains, Jantz said.

Years ago when she first started working with families, Jantz said, staff was reluctant to say too much because they didn't want to upset anyone. What she's realized over time, however, is that sons, daughters, siblings and grandchildren actually are curious and eager to learn more about a donor's time at UT.

WHAT COMES NEXT

When she taught science in the Washington, D.C. area, Denton told her students she might just donate her body so her skeleton could be displayed one day in the classroom.

"And they said, Mrs. Denton, who will we know it's you? And I said, Look at these teeth!" she recalled, opening wide.

That was before Denton know about the Body Farm. She became interested in becoming a donor after moving with her husband, the retired head of the Office of Nuclear Reactor Regulation at the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, in the 1990s.

She read Bill Bass's books, fiction and non-fiction, and she even met the retired forensic anthropologist, ultimately telling him she wanted to be part of the program. He told her how to sign up.

In Denton's family, they talk about her decision to donate often, she said. Harold Denton was cremated after his death four years ago. When he died, the family eventually gathered to celebrate his life over a long weekend in the North Carolina mountains.

That's how Denton prefers it. No funeral.

Every Sunday when she was a child in Rocky Mount, Denton's family would go out to the cemetery to see her grandfather and the family plot. They fixed the flowers, tended to the grass.

Little Lucinda had her own assignment.

"They made me take a toothbrush and a little bucket of water to clean the bird poop off of the tombstone. So I have a very negative feeling about tombstones," she said.

Denton hopes there is a hereafter, but she's not convinced anyone's proved it actually exists.

Instead, she's focused on living a full life. Three years ago she went hang-gliding with her son. She loved to ride rollercoasters until her orthopedic surgeon told her it was time to stop.

When her time comes, off she'll go to the Body Farm - the next chapter of the journey.

"I want it to be used for something good, so I feel like the Body Farm and all of the scientists there can have use for my body. I won't know what. But whatever it is, I'm game!"