KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — The moment felt like one of those end-of-the-world movies where everything turned pitch black but the character was still alive.

The 110-story South Tower of the World Trade Center had just come thundering down, hurtling debris across multiple blocks and shrouding lower Manhattan in a curtain of gray-tan dust.

But 32-year-old Amy Mundorff, her head covered by her Kevlar New York City Medical Examiner's Office jacket, had survived.

"I remember saying, 'I'm alive. Is anyone else out there? It was black. I couldn't see anything," the forensic anthropologist told WBIR recently.

Today, Mundorff is an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Tennessee. On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, she was trying to do her job as a forensic anthropologist with the Medical Examiner's Office when she became swept up in one of the most significant events of the 21st century.

Every day, in some way, Mundorff confronts what happened Sept. 11. Her body is one testament: Along with a severe blow to the head, she suffered fractures to her neck that morning which have resulted in several surgeries.

She also breathed in ash and debris that caused sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease, in her lungs. For many it can be fatal.

But Mundorff doesn't wallow in the negative.

She's grateful for her husband, Kurt, who helped her through years of rough times and for the daughter born after the attacks. She's delighted she ended up in Knoxville at the University of Tennessee.

"I was very lucky," she recalled from the living room of her North Knoxville home. "And everyone who was down there from my office lived. People had a lot of injuries. Some people didn't come back after. But we were very, very lucky."

'WE JUST CRIED'

After the South Tower -- the first to go down -- collapsed, Mundorff and colleagues who also had responded to the scene after the attack evacuated across the Hudson River to New Jersey.

They needed medical help quickly, and the North Tower was soon to fall down as well, enveloping the financial district in even more dangerous dust and detritus.

"We sat on the shore just in shock and and then watched the North Tower crumble. It was so surreal, just seeing one building and realizing everyone in it was gone. Just one minute it was there. And then the North Tower fell, and everyone else was gone. And it was nauseating. And we just cried," she said.

Despite multiple welts, two black eyes and that concussion, Mundorff didn't stay away from work long.

By Sept. 13, 2001, she was back doing her job: Helping the Medical Examiner's Office identify the remains of the more than 2,700 people who died in the New York attack.

Identifying disaster victims is one of her specialties.

"We were a team. And so if there was a victim on the table that somebody knew -- and that happened -- we all stopped together. We all consoled each other we took care of each other," she said.

It's been painstaking work that's still going on, 20 years later. Just this week, NBC reported, recovered remains have been confirmed through DNA analysis to be those of a Hempstead, N.Y., woman and a man whose family declined to release his name.

The process proved laborious in part because authorities had to figure out just who might be missing. The thousands of people who potentially were in the Twin Towers on the morning of Sept. 11 created an "open population," similar to a miniature city.

Mundorff said there were multiple reports of the same person missing, perhaps with a slightly different name. There were multiple people who shared the same first and last name. There were fathers and sons with the same home address.

Then there was the challenge of matching a person's known identifiers -- fingerprints if you were lucky or genetic material if you had to work harder -- with all the remains collected around Ground Zero.

Some 22,000 fragments were collected and catalogued; 5,000 pieces were an inch or smaller, she said.

All had to be tracked as they made their way through the testing process.

"I don't think people understood the logistics, how complicated they were," Mundorff said. "And that was all being done while we were doing it. Because there was this sense of urgency to get the IDs."

Another wrinkle no one had originally considered: the fact that human remains could be mixed together. The physical force of the tower collapses drove the flesh of some victims onto the bones or cavities of others. But that was something the forensics teams didn't realize until they started getting conflicting DNA data results.

Mundorff spent several years on the identification effort. But by 2004, she said her family could see her healing had plateaued and it was time to get out of New York.

She and husband Kurt moved to Canada, where she got a doctorate and thought about her next steps.

HOME IN KNOXVILLE

Ultimately, she ended up in 2010 at the University of Tennessee, renowned for its forensic anthropology department. The university allows her to do practical research on victim identification and mass graves as well as work with smart students.

"I have phenomenal colleagues. My department is supportive. My grad students are brilliant. Our undergrads are super keen. I do the research I want. I teach the classes that I love," she said.

She's been here 11 years, the longest she's lived anywhere since she was a schoolgirl in Connecticut.

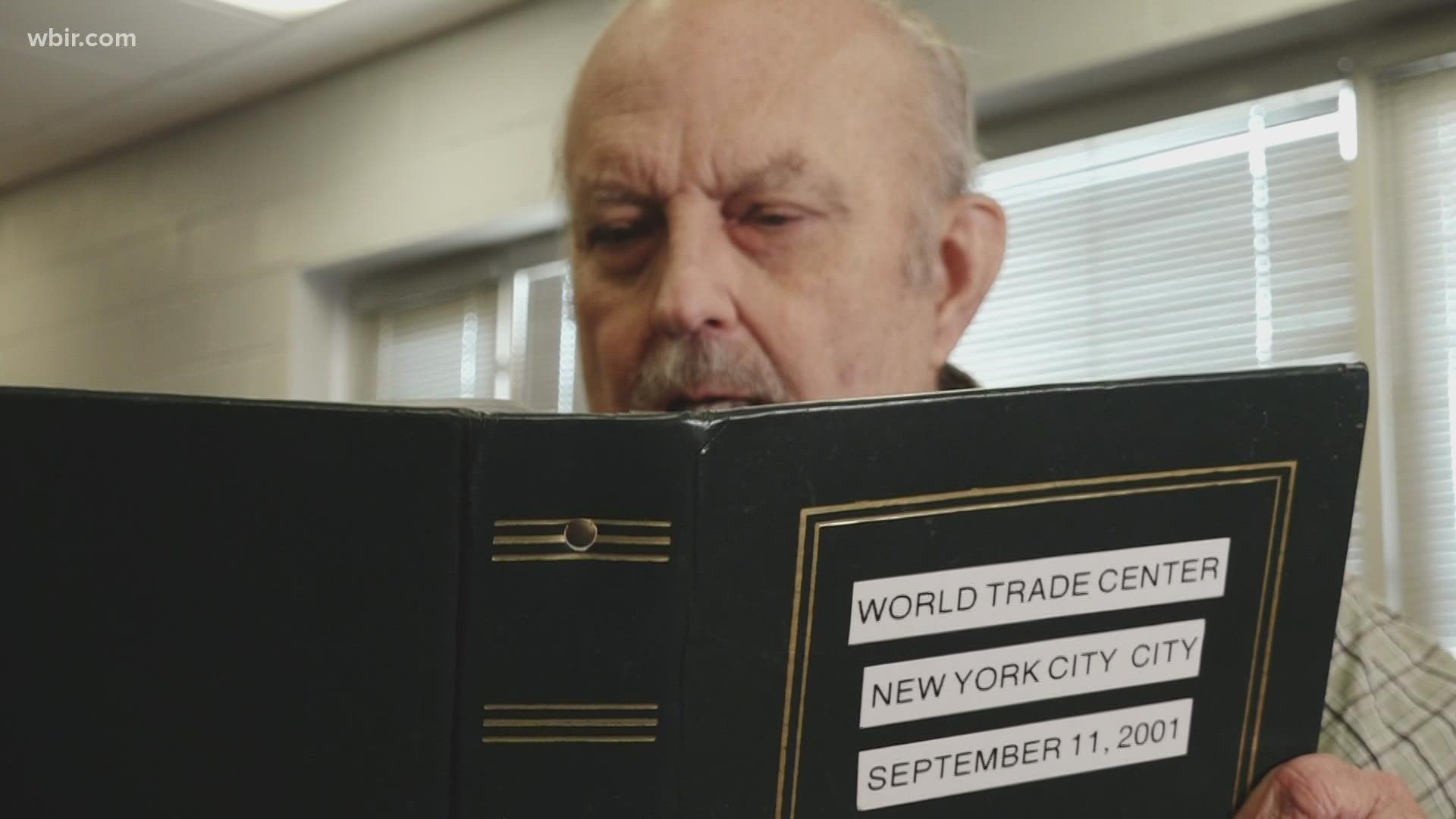

While Mundorff doesn't look at it often, she keeps mementoes and artifacts from her time in New York in an old container. It includes her IDs, letters, photographs, some newspaper, paintings made by children after the disaster, the hard hat she wore down at the site, and a container that includes chunks of debris found her coat pockets after the South Tower went down.

The Examiner's Office jacket Mundorff wore that morning is now part of the collection of the 9/11 Memorial and Museum at the original WTC site.

Twenty years on, Mundorff wants people to remember how resilient the population was then, and how everyone reacted when they fully absorbed the depth and loss of the attacks.

"I don't think that people remember how much we all pulled together. I think right now in particular, there's...there's so much separation. And there's so much anger and hatred and disharmony. And there was something about 9/11 that made people care about each other again," she said.

And in New York, the efforts to match some 1,000 terror victims with all those human remains goes on.