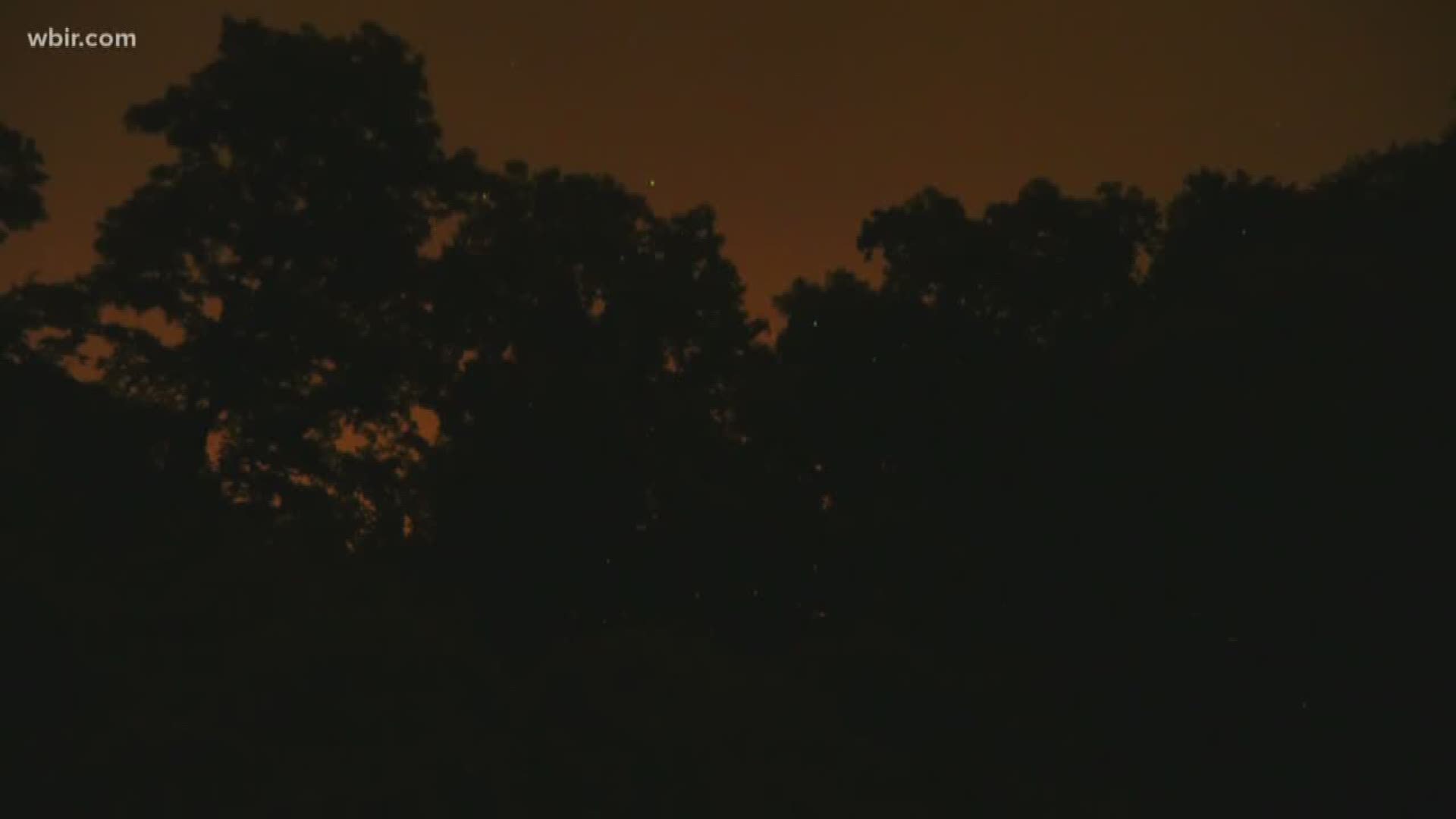

Elkmont, Tenn. — Elkmont, Tenn. - On Thursday, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park will start shuttling thousands of lucky people to the highly anticipated synchronous firefly show in Elkmont.

The week-long event runs from June 7-14. In April, the park announced the date of the viewing and held a lottery for trolley tickets. Predicting when the fireflies will be at their peak so many weeks in advance is both a science and a gamble.

"Nature goes by its own schedule. It's always a gamble," said Lynn Faust, a firefly expert who discovered the synchronous fireflies in Elkmont in the early 1990s. "The peak for the synchronous species in the Smokies has been as early as mid-May until late-June, so there's around a five-week range. I always feel stress for the park folks who have to guess in April, because so much can change in a month. But the park has to hold a lottery, advertise, and schedule shuttles, so there's no way around it."

The peak for fireflies changes with the weather. Faust makes her predictions based on an agricultural formula of degree-days. She keeps track of the cumulative temperature of the ground, much like farmers do to predict the best times to plant and harvest crops.

"Our lightning bugs develop according to how warm or cool it has been. I have a device that logs the ground temperature beginning of March. Becky Nichols, the entomologist for the park, also takes the same measurements and is very good at predicting when the peak will be. We compare notes and I try to help, but I'm really glad I don't have to be the one who tells the park in April when to schedule the shuttles," said Faust.

Think of it like predicting how long it will take to bake a cake without knowing what the temperature of the oven will be. This year was especially tricky with an unseasonably cold April followed by the second-warmest May on record.

"That really messes up predictions, but I think the park has probably timed things pretty well. I'm expecting peak in the next week," said Faust. "We are hoping for a good year. I feel like these people who have worked so hard to get their shuttle tickets and driven from who-knows-how-far deserve to have a really beautiful experience."

Faust keeps track of dozens of species throughout the Southeast. She wrote the first field guide for lightning bugs across the eastern and central United States and Canada.

Along with offering her opinion to the National Park Service, this spring she has helped BBC Nature with a lightning bug shoot and provided guidance to a young romantic.

"Everybody wants set dates. I have people everywhere calling me. But my favorite this year is the man that's going to propose to his lady-love and he wants the fireflies flashing in the background. He's not doing this at the event at the park, but we've been helping him and I really hope she says yes," said Faust. "Lightning bugs are romantic. I have countless people who are complete strangers tell me their child was a 'firefly baby.' This is a time for lightning bugs to mate and apparently has an effect on people, too."

The romantic tone of firefly viewing is fitting because love is in the air for lightning bugs. The insects spend a year or two underground and emerge from the soil in the final stage of life. Then the glowing beetles go out in a romantic blaze of glory. The insects fly, flash, mate, lay eggs, and die.

The insects flying around flashing are males while females are on the ground. The flash is a call-and-response mating ritual. All the males flash and compete with each other while watching for a female to respond with an invitational-flash to mate.

The synchronous species in the Great Smoky Mountains does not flash in perfect unison. What makes them synchronous is they flash together for several seconds and then stop flashing as a group. The silence is also synchronous.

Think of it like a bunch of guys shouting for the attention of a woman they cannot see. All the guys are yelling, but then everyone agrees to shut up for a few seconds so they can hear if a woman responds.

In the case of synchronous fireflies, the males flash like crazy for 5 to 10 seconds, then the forest goes pitch black for 5 seconds while males look for a female to flash on the ground. If all the males were constantly flashing, it would be more difficult to spot a mate amid all the lights.

Degree-days help predict when crops and insects will be at their peak. Then there's the whole other matter of how good the crop will be. In 2017, the light show was relatively dim after prolonged drought and demolition in Elkmont took a toll on the synchronous firefly population.