OAK RIDGE, Tenn. — Scientists in Oak Ridge are working to develop lifesaving drones that can help locate and rescue missing people. The emerging technology is intriguing to crews in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP) who embark on roughly 100 search and rescue missions every year.

"We look at emerging technology and if it means the difference between life and death, we'll certainly try it," said GSMNP ranger Jared St. Clair. "They are still evolving and can become another tool we use regularly, just like infrared and night vision technology was new for us a few decades ago."

When discussing drones, St. Clair emphasizes there is no substitute for trained searchers on the ground and eyes in the air from helicopter crews. He thinks the technology can become an additional tool to accompany the already proven methods of search and rescue.

"The huge advantage of the drones is you're not putting anyone at risk. You can use them when the clouds are lower. They can fly in conditions that wouldn't be safe for a helicopter crew. Sometimes weather between a search area and an airport can keep helicopters grounded, where the drone can take off from the search area," said St. Clair.

The National Park Service called on Oak Ridge National Laboratory's drone team for help with a large search in late-September 2018 for missing Ohio woman Susan Clements.

"We had not used drones before that particular search," said St. Clair. "The drones we were using came from Oak Ridge. They had capabilities on there that we didn't have."

"That was the first time we responded to an actual emergency. We learned a lot of lessons we can apply for the future," said Andrew Harter, ORNL research scientist.

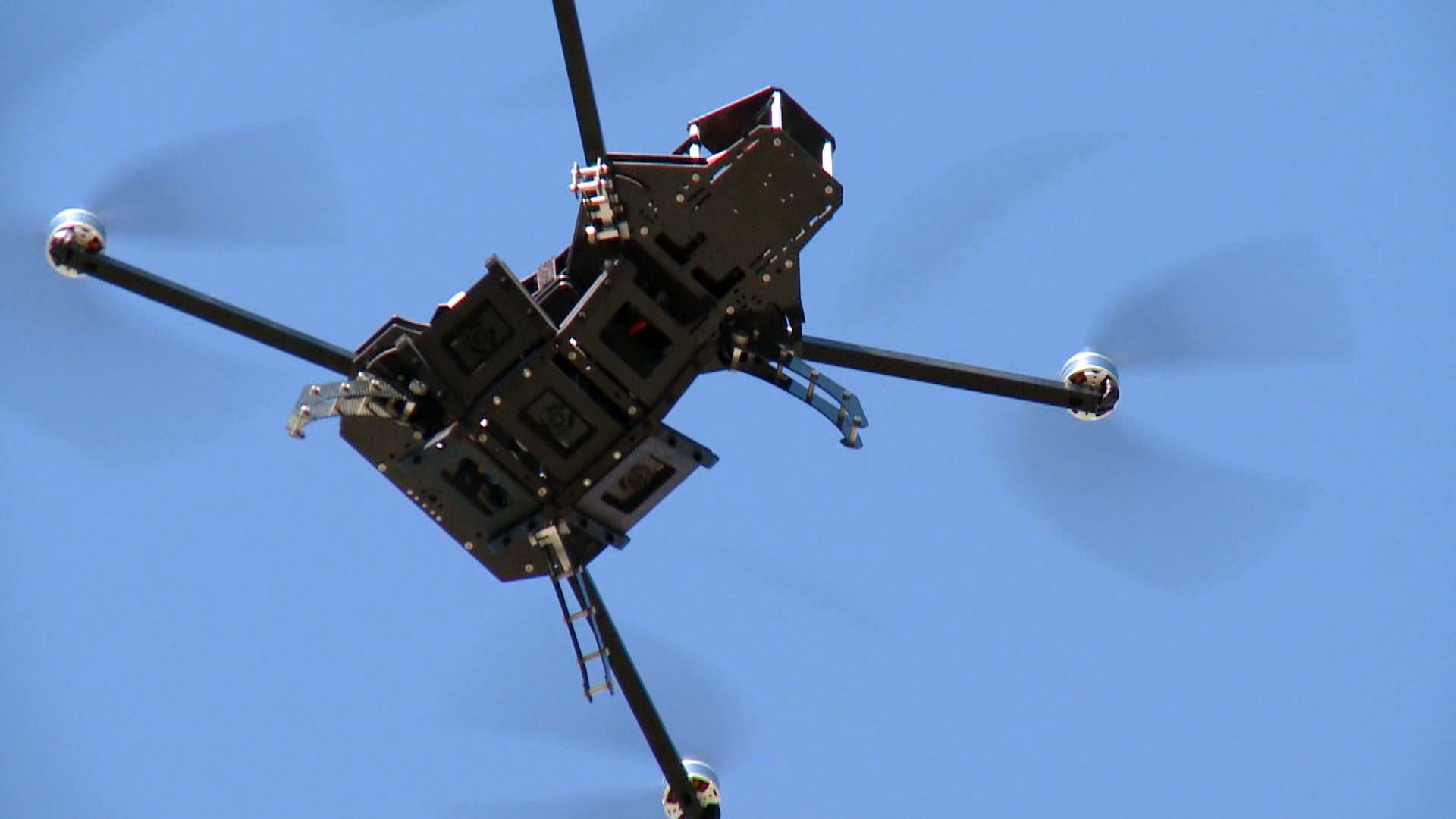

ORNL's unmanned vehicles include various copters and fixed-wing aircraft, some of them designed in-house. Whatever type of vehicle is used, they are all considered "platforms" to carry technology such as high-resolution cameras and thermal sensors.

"We use the drones as tools to collect that data. The magic really happens with what we do with that data on the back end," said Andrew Duncan, a pilot for ORNL's unmanned systems.

In the Susan Clements search, the drone took thousands of high-resolution pictures of the scene and stitched the photographs together for one large snapshot of the search area. ORNL's computing power can quickly process and complete what would be a prolonged manual task.

"It is speed. How much faster we're able to stitch the images together," said Brad Stinson, an electrical engineer for ORNL's autonomous systems group. "Our initial idea was to take all of these photos and scan for any pixels that matched the color of the missing person's clothes. Then when we got there, we realized she was wearing colors that matched the terrain."

Clements was wearing green and grey. The colors were impossible to pick out of a rocky landscape canopied by a green forest.

The ORNL team shifted the photos to a new purpose by creating real-time maps of a mountain landscape that constantly changes due to rockslides, erosion, and shifting drainage areas.

"So having real-time information is very important for us because a map may not capture what's really out there right now," said St. Clair.

The ORNL systems take the high-resolution photos from the drones and create mosaic three-dimensional maps to reveal the exact terrain crews have to navigate. It can reveal rockslides, downed trees, and help crews plan the fastest routes possible.

"In as near to real-time as possible, we can take that imagery and convert it to a very accurate detailed imagery of the area," said Stinson.

After a week-long search, crews found Clements body in a rugged drainage area a couple of miles from Clingmans Dome. She died from hypothermia on a cold and rain-soaked mountain, likely on the first night she was missing before any search could have saved her.

"We had high hopes of actually finding the individual," said Harter. "It did not work out the way anyone wanted it to and was just a very difficult situation."

The first search attempt ended with tragedy, but still marked the beginning of a real-world learning process.

"We were really severely limited by the weather and by the fog. If we're going to respond to something like this in the future, we need sensors that can operate through fog and not have to worry about what the weather's doing," said Harter. "You also have to deal with limited connectivity in these remote areas, so we need to make sure we have systems that can operate and communicate anywhere."

The need for high-speed wireless networks is especially important for ORNL as it develops a network of aircraft that depend heavily on internet access.

"We're kind of transforming the way we do drones. We're connecting them to the internet. Unmanned vehicles and autonomous vehicles are really going to be the future," said Duncan.

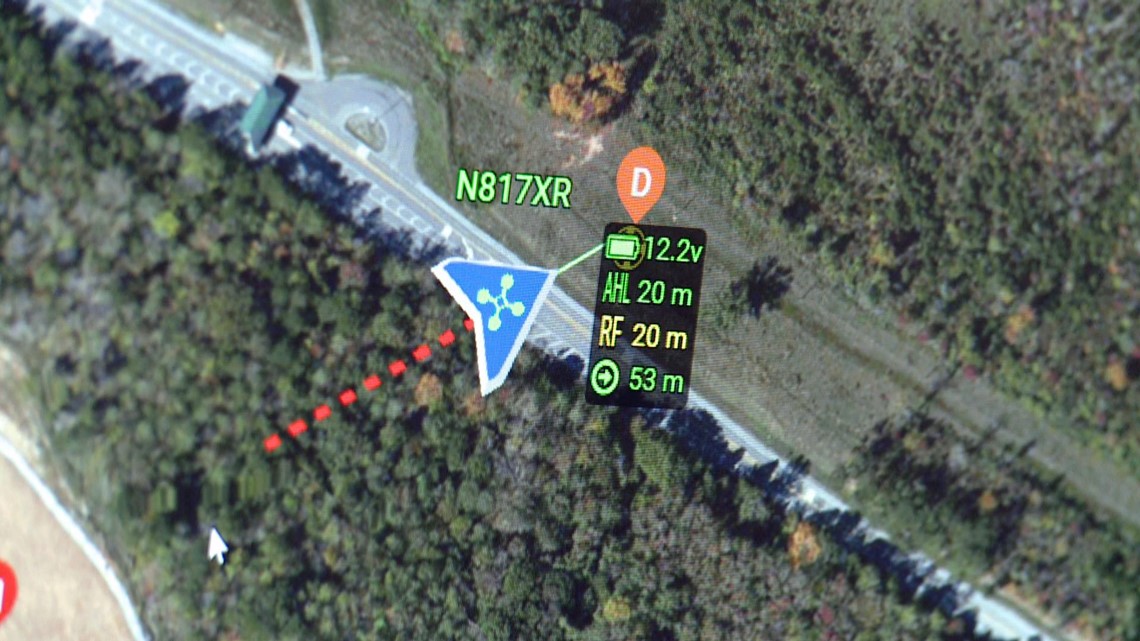

Current FAA regulations require drone pilots to remain within a certain distance of the unmanned vehicle. ORNL is dreaming of a time when robust drones are given limitless range and can be controlled with a few clicks on a map.

"We want to develop drones that basically fly themselves and you don't have to be a trained pilot to operate one in a search and rescue or other emergency situation," said Stinson. "We're developing a system where you can click a few buttons, the drone will take off, and if I want to send it somewhere it is relatively easy. This is powerful in that we can control these vehicles from essentially anywhere in the world."

Improving the speed and strength of connections to drones could make them a standard piece of safety equipment installed at any location. The vehicles could standby, ready to launch in an emergency.

"Think about a situation like a chemical spill. You have a plume of toxic materials in the air, you don't want to send people into that environment to find out what's going on. You can launch drones with sensors that detect what substances are in the air, their concentration, and what direction they're being carried in the air," said Harter.

St. Clair reiterated the drones are still new tools that need advancements before they are a vital part of search and rescue missions.

"Right now, I don't think they are as good as having an actual person in the air who can see what's going on. But I expect them to find new ways to use drones, maybe in ways we're not thinking about right now. As they evolve, if they can help us save lives, we will use them," said St. Clair.

As for visitors who may want to fly their personal drones in the national parks, the unmanned aircraft are banned.

Flying a drone in a national park can cost you. Rangers can write tickets for a misdemeanor violation that is typically accompanied by a $75 fine. However, the penalties can go much higher to include a mandatory court appearance. A judge then has the authority to issue a $5,000 fine and/or 6 months in jail for the violation.