The Oak Ridge man facing deportation for his role as a German concentration camp guard during World War II will appeal the judge's decision.

Knoxville attorney Hugh Ward, who represents Friedrich "Fritz" Berger, would not comment Wednesday about his client's case but confirmed an appeal will go forward.

The U.S. Department of Justice announced last week that an immigration judge in Memphis had ordered Berger's deportation after a two-day trial. The judge concluded Berger, age 94, who has lived more than 60 years in the United States, could be forced out by existing federal law for what he did during the war.

Berger's case has drawn international attention. The DOJ has been working for decades to identify and address anyone with ties to the Nazi "machinery of oppression" during the war.

Berger was a member of the German Navy assigned to become a camp guard, according to stipulated testimony from Berger's trial obtained by WBIR. Ward said his client was not a Nazi and was never accused of war atrocities.

Adolf Hitler's government seized millions of innocent people during World War II, from Jews to the Roma to homosexuals.

Many were ordered to prison or concentration camps. Many were exterminated.

Berger declined Wednesday to talk with WBIR.

Neighbor Kathy Turner said she'd been surprised to learn this month that Berger guarded prisoners at a Nazi camp.

"I just thought he was an elderly German guy," she said of the man who lives about six doors down. "I knew that he was German, but I didn’t know anything about him. He seemed to keep to himself."

Helene Sinnreich is an associate professor in the University of Tennessee's Department of Religious Studies and director of the Fern and Manfred Steinfeld Program in Judaic Studies.

Sinnreich said people like Berger helped the Nazis do their evil.

"This is a part of genocide and we can’t allow perpetrators of genocide to go unpunished," she said.

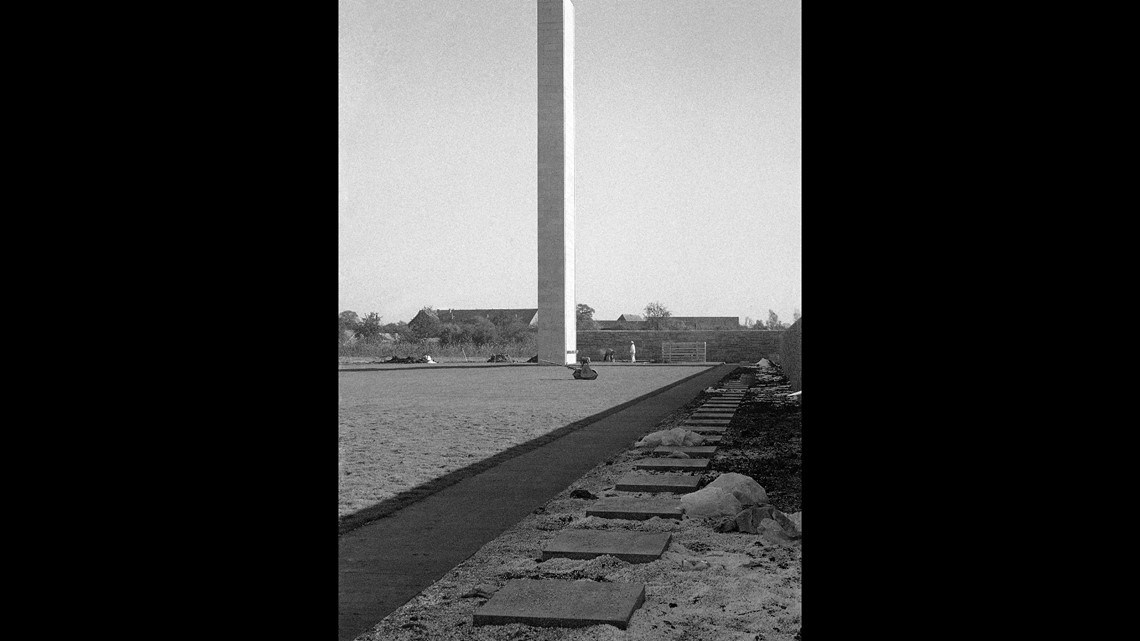

MEPPEN CONCENTRATION CAMP

According to the DOJ, "The court found that Berger served at a Neuengamme sub-camp near Meppen, Germany, and that the prisoners there included 'Jews, Poles, Russians, Danes, Dutch, Latvians, French, Italians, and political opponents” of the Nazis. The largest groups of prisoners were Russian, Dutch and Polish civilians."

Court records offer a more detailed look at Berger and his background. He was born in what was then Germany in October 1925.

In 1943, like thousands of young men in Germany, he was conscripted into the German civilian labor service and sent to France. He joined the German Navy rather than be drafted into the Army, according to records.

In January 1945, his naval unit was assigned to the Neuengamme sub-camp near Meppen close to the Dutch border. He was age 19 at the time.

Berger and his peers guarded camp prisoners, according to stipulated testimony.

"Mr. Berger understood that the SS operated the Meppen camps, but he was supervised by naval personnel," records state. "Mr. Berger and the other navy guards wore a navy land uniform which did not have an SS insignia. Mr. Berger was not given an SS blood type tattoo."

The SS served as the black-uniformed elite corps of the Nazi Party.

It was Berger's job to help escort prisoners to worksites outside the subcamp, to watch over them at the sites so that they didn't escape and to take them back at the end of the day.

Sinnreich said the camp had a high death rate and subjected prisoners to "horrible conditions."

"They were subjected to forced labor. They were essentially slaves," she said.

Thousands of prisoners died in the Neuengamme system during its operation.

Berger didn't ask to be transferred from Meppen, according to the DOJ.

He was there until late March 1945, the court found, and also helped with a forced two-week march of prisoners in the closing days of the war to the main Neuengamme camp near Hamburg.

At the time the allies were closing in. An estimated 70 prisoners died during the forced march, according to the government.

Germany began to collapse in April. Hitler committed suicide in April 1945, signaling the end of the war.

"In April 1945," according to the stipulated testimony, "Mr. Berger and others fled into the woods and were coaxed to surrender."

The British Army took him prisoner. They held him as a prisoner of war until Christmas Eve, 1945.

"He was subsequently employed by the British as a truck driver into 1946," stipulated testimony states. "The British did not charge Mr. Berger or contact him as a potential witness during their war crimes investigation of Neuengamme subcamp personnel."

He moved to Canada with a wife and daughter in 1956 and then arrived in the United States in July 1959.

AFTER THE WAR

Berger draws a German pension for work he did in his home country including his wartime service.

"Mr. Berger regularly renewed his permanent resident immigration status without incident," according to records. "He has had no adverse encounters with the law. He was regularly employed and retired to Oak Ridge, Tennessee."

Sinnreich said it's ironic that Berger ended up living among survivors of the Holocaust in Oak Ridge.

The US government is right to find and deport such people, she said. It sends the right signal, she said.

"I think it’s important for us to recognize these crimes that took place -- to not excuse them because time has passed and to keep in mind that it is always possible in various situations to have genocide arise again," she said.