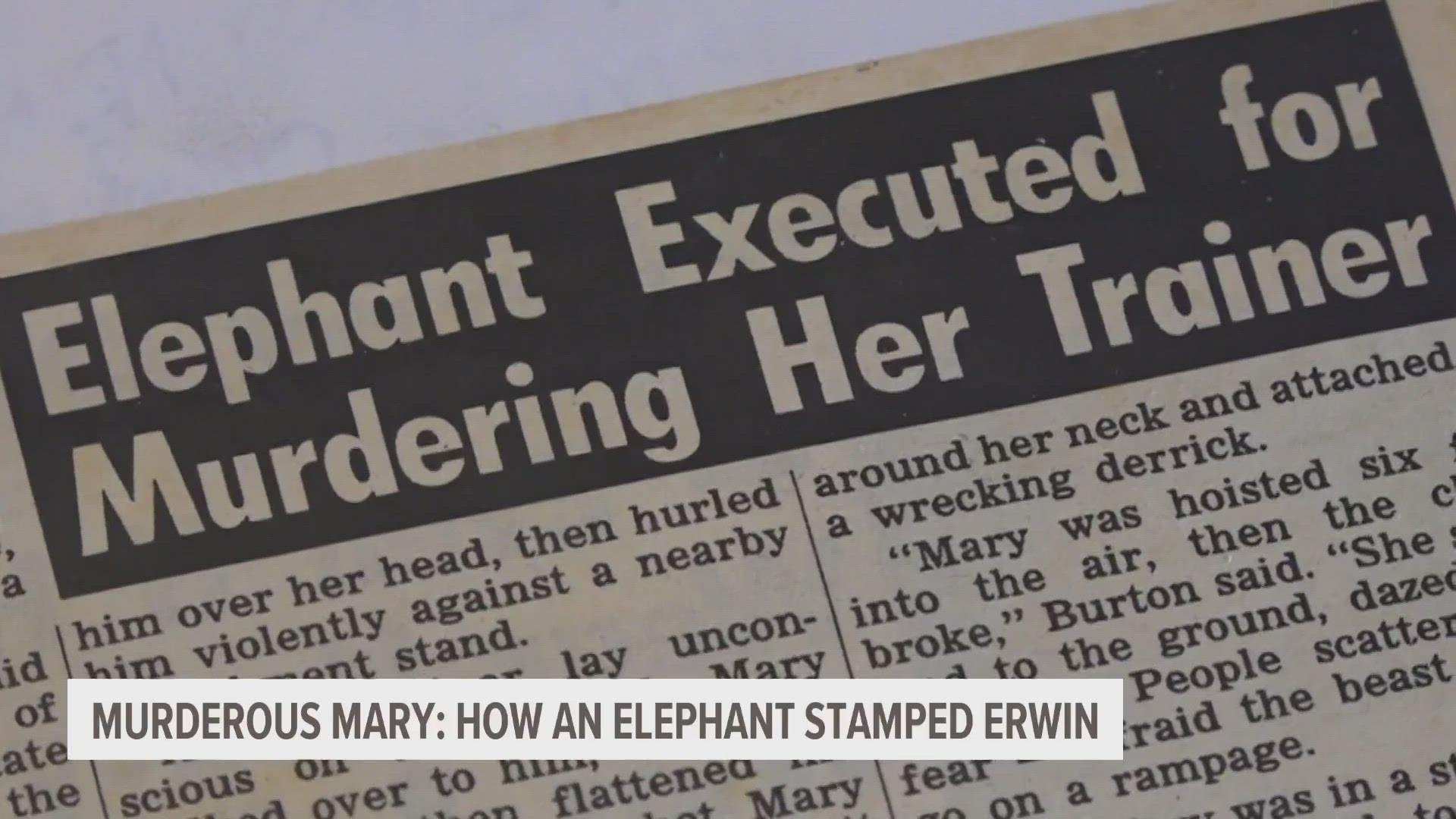

The hanging of Mary the elephant: TN town wrestles with legacy of circus animal's death

Mary was killed in 1916 after she grabbed, slammed, and stomped her handler.

Buried near a creek on the west side of the wide Erwin railyard is a circus elephant.

Many have tried to find her. Many are the myths about her.

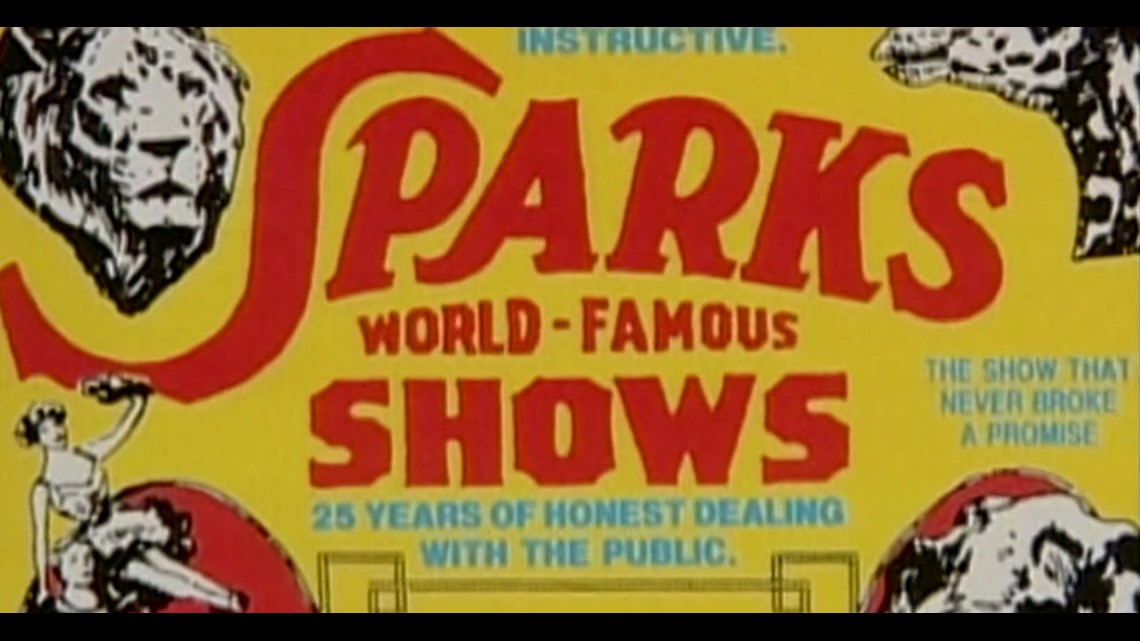

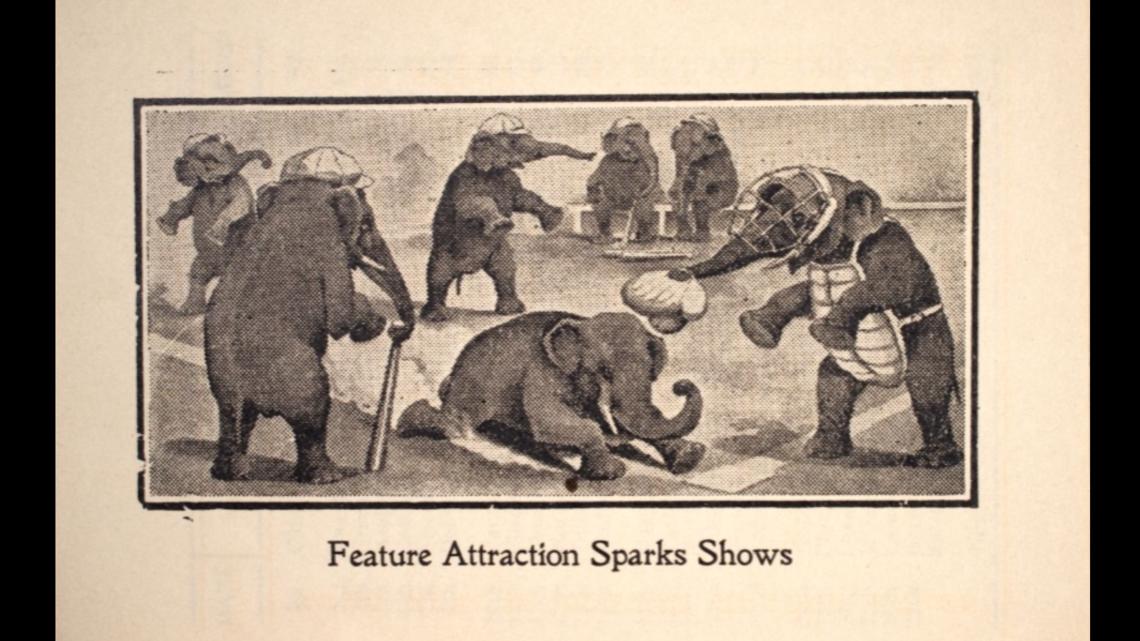

An Asian elephant of 20-some years, Mary performed for Sparks World Famous Shows to audiences from Warsaw, N.C., to Bangor, Maine, to Velva, N.D., and all points in between. It wasn't the Greatest Show on Earth, but it always drew a crowd when the train pulled into town.

Billed with showbiz hyperbole as "The Largest Living Land Animal on Earth," Mary proved a star attraction for Sparks until she killed a man in Kingsport, Tennessee. He made her mad, so she snatched him off her back with her trunk, flung him to the ground and stomped on his head.

It was curtains for the elephant. Sparks couldn’t keep a murderous Mary.

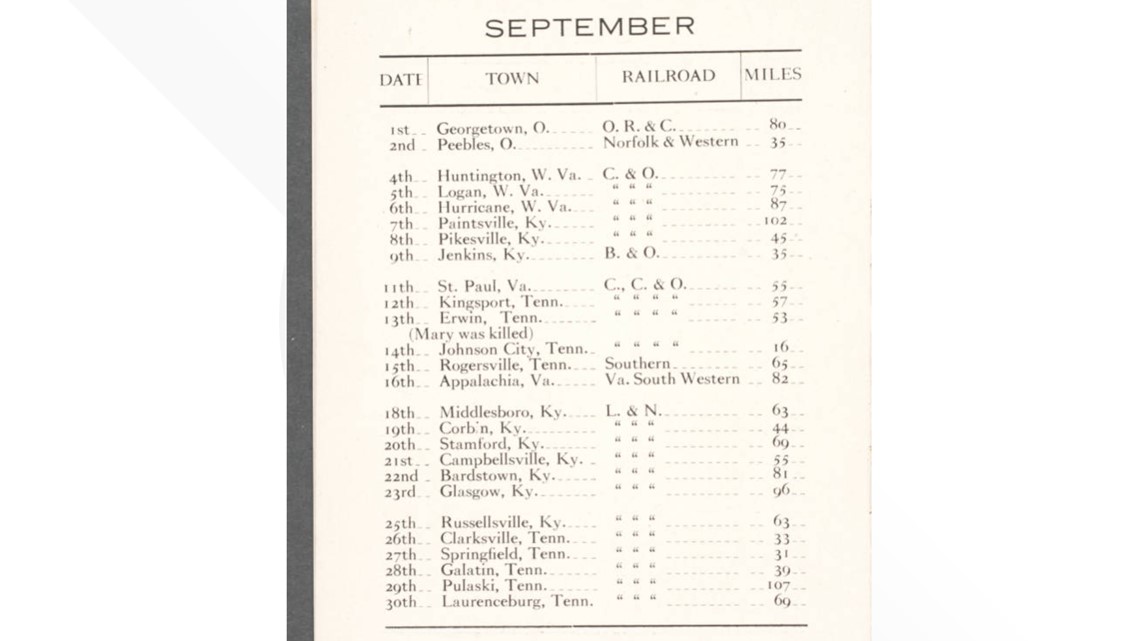

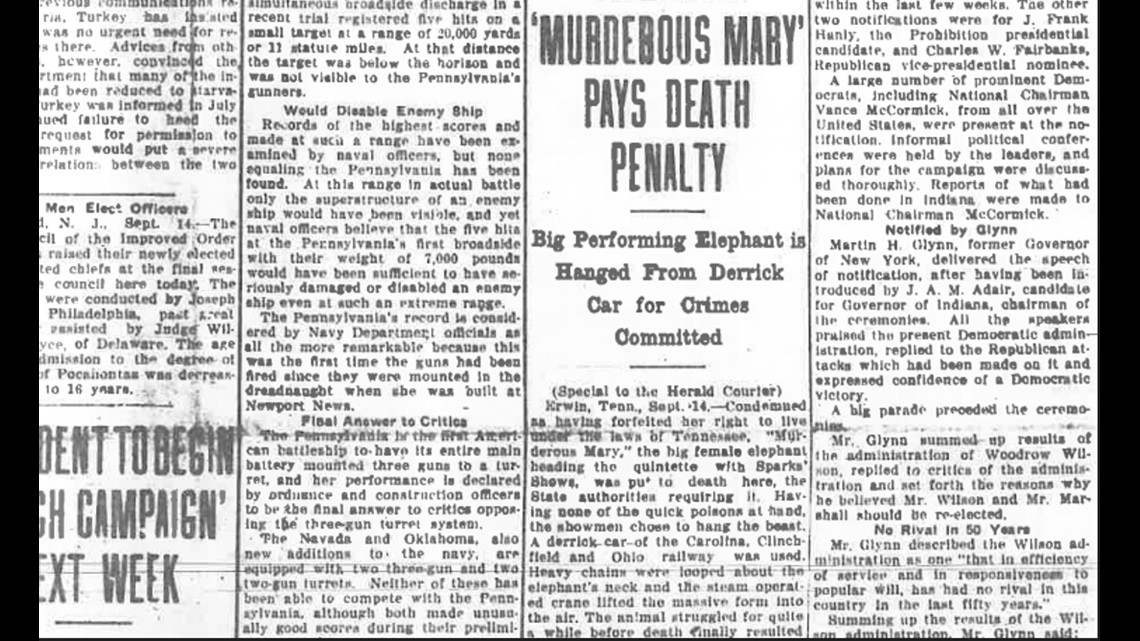

On the afternoon of Sept. 13, 1916, a Clinchfield Railroad man hoisted her up on a chain from a 100-ton wrecking derrick in the Erwin rail yard and hanged her. Thousands watched.

When witnesses were satisfied she'd died, they rolled her body down the far west side of the yard, dropped her in a freshly dug pit and covered her up.

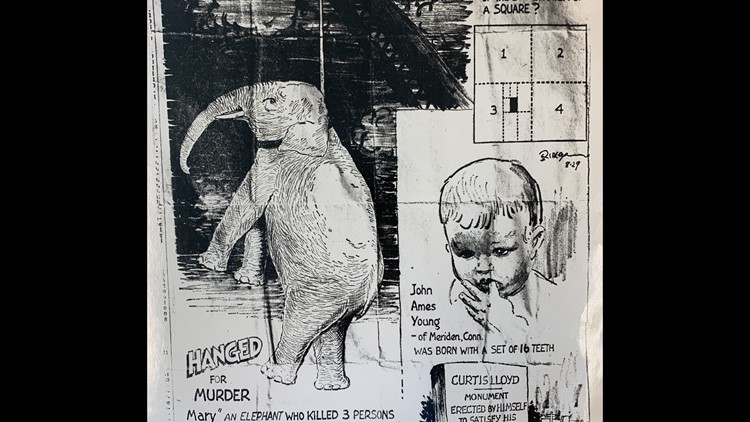

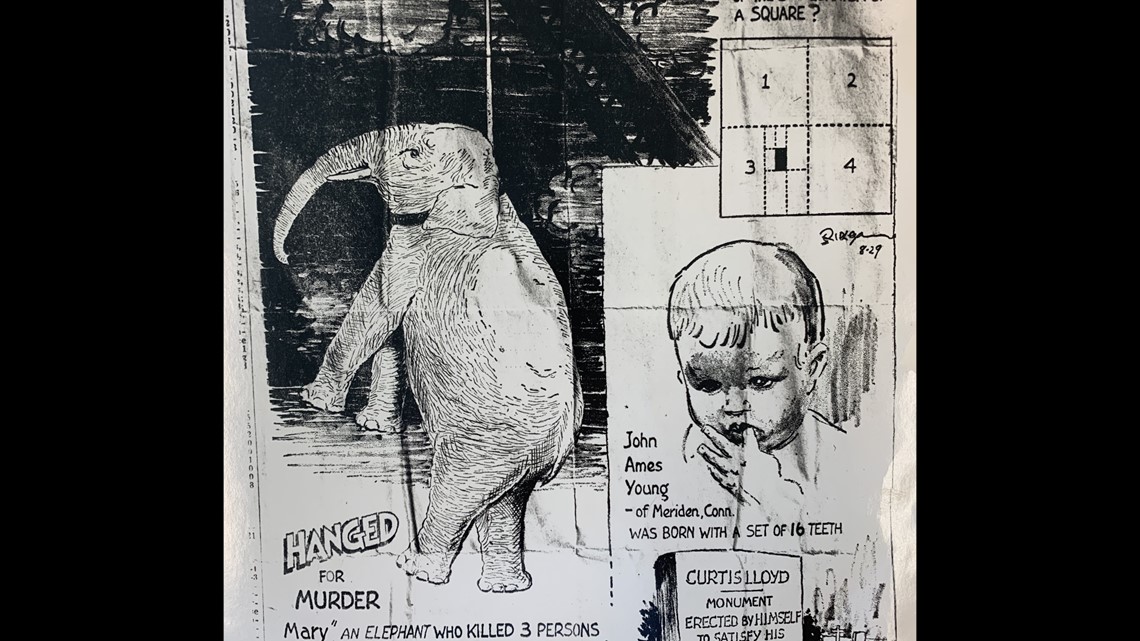

Dead more than 100 years, Mary remains a fascination today. Her story has been featured on National Public Radio, in documentaries, a play, the tabloid National Enquirer, newspapers in Europe, and in Ripley's Believe It Or Not.

WBIR sought permission last month from rail yard owner CSX to look for Mary's burial site. No, came the answer. It's private property, a CSX spokeswoman at headquarters in Jacksonville, Florida, replied.

"It's a misunderstood tragedy," said Martha Erwin, curator of the Unicoi County Heritage Museum and adjoining Clinchfield Railroad Museum.

Erwin's great-uncle witnessed the 1916 hanging and wrote about it in a report that appeared days later in a Knoxville newspaper.

"This is a subject that's hard to talk about because we were never allowed to speak on it," Erwin said.

Erwinites answer questions politely about their town's macabre moment in history.

Yes, the elephant died here, they say. But we're not the ones that killed her.

The story really started in Kingsport, they say. That's where they should have done the hanging.

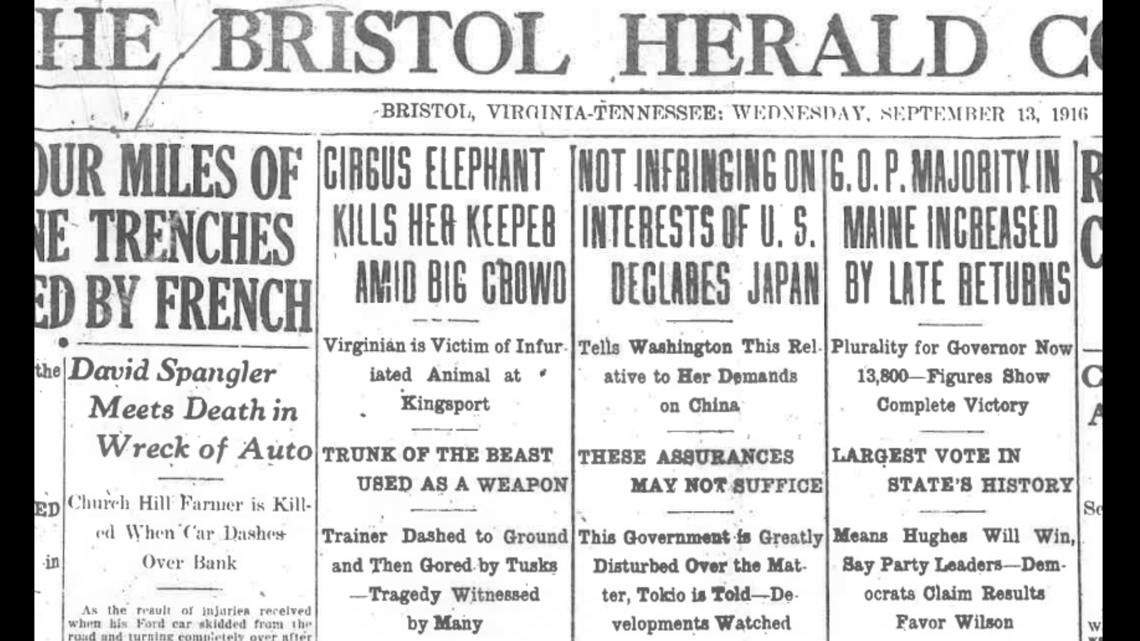

Circus elephant kills her keeper amid big crowd

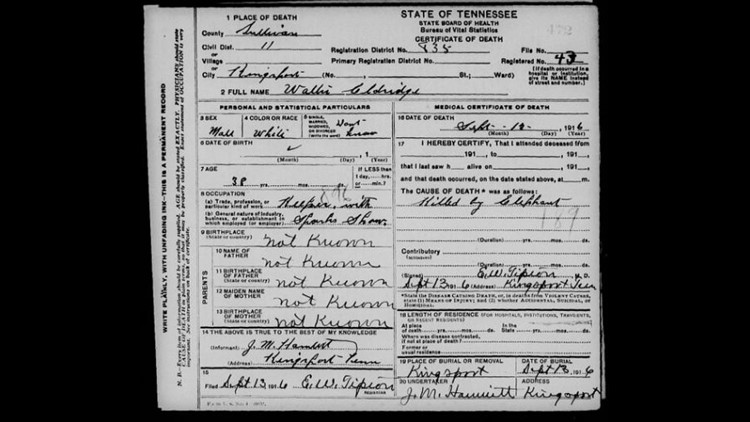

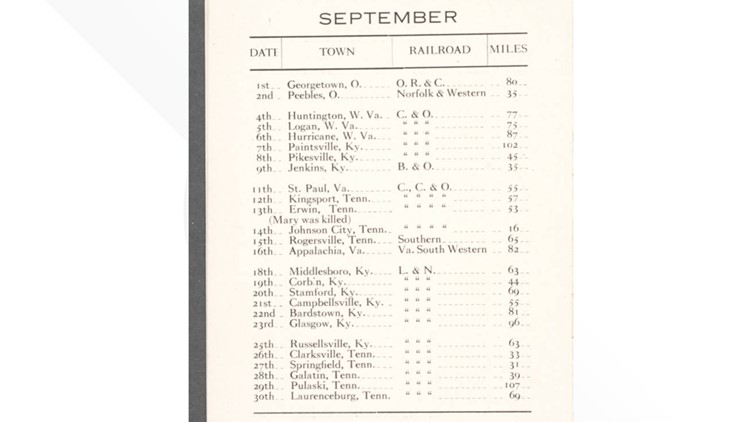

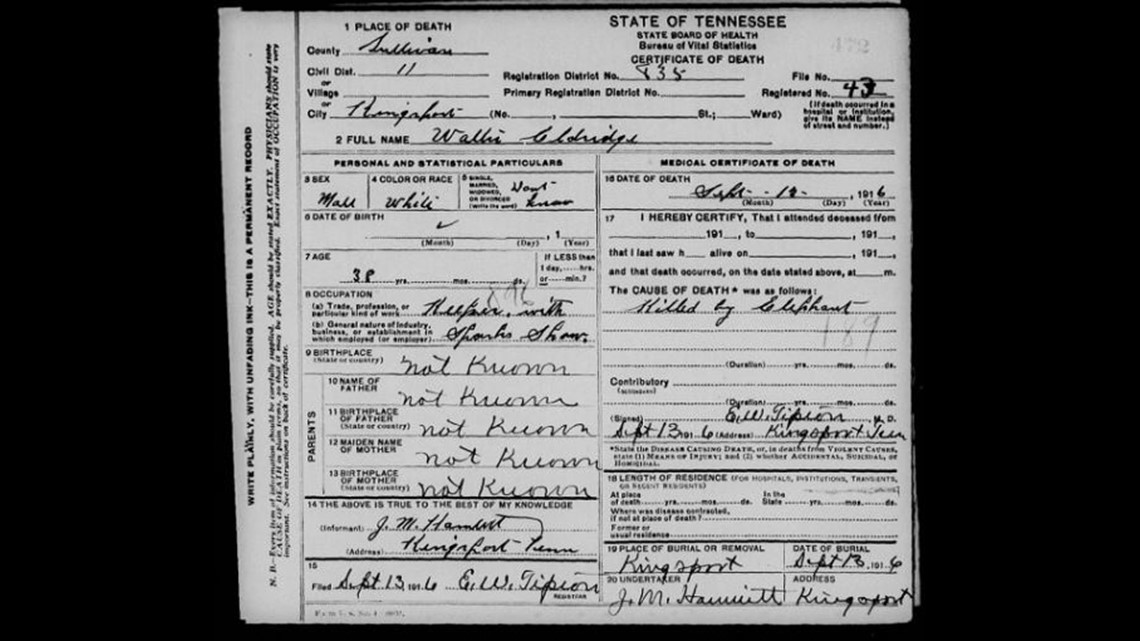

Sparks World Famous Shows hired Walter "Red" Eldridge on Sept. 11, 1916, in St. Paul, Virginia.

Eldridge, it appears, was a rolling stone -- a handyman, janitor and porter at a hotel in town, historian and author Charles Edwin Price wrote in his 1992 account "The Day They Hung the Elephant." Red lived in St. Paul but it appears he came originally from the Midwest.

When the circus eased into St. Paul for the day, Eldridge jumped at the chance to hire on as an assistant elephant handler. He knew nothing about pachyderms.

The next morning, the circus train made the 55-mile trip over to Kingsport, a town of about 5,500 tucked in the northeast corner of Tennessee.

Sparks was not a big circus. By author Price's reckoning, it used about 10 rail cars, traveling annually throughout the South, Midwest, Upper Midwest and New England.

Charlie Sparks, who inherited the big top from his father in the 1890s, could boast of "20 funny clowns," acrobats, barking seals and a handful of elephants, including Mary, records in the Archives of Appalachia at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City show.

Sparks newspaper ads proclaimed it "The Show That Never Broke A Promise," complete with "Perfect specimens of the Earth's most curious creatures gathered together into one immense menagerie."

Crowds loved 5-ton "Big Mary," and Sparks loved showing her off. She was worth thousands of dollars to the showman, never mind the rumors that she'd killed at least one man in the past.

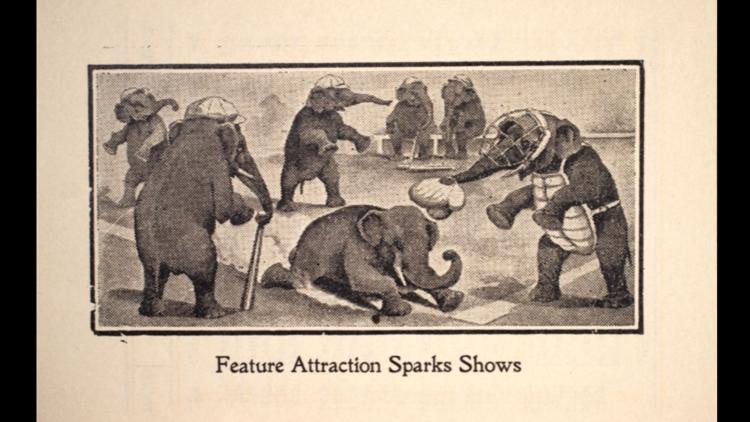

She pitched the ball in mock baseball games. She took a lead role in the parade whenever the show came to town.

On this particular September day, Eldridge rode Mary’s back for a stroll through town. It was almost certainly one of the few times he'd ever ridden an elephant, let alone Mary.

The assembly made its way through Kingsport. Onlookers watched from the side. Among those was a country girl of about 5 years old named Alma Brown.

Alma's mother had carried her into town in a buggy to see the circus, her first time ever.

"They were bringing 'em up Sullivan Street, taking them to water," Brown told WBIR's "Heartland Series" host Bill Landry years later. "My mother and a lot of other folks had their children up in these paths to watch the elephants being taken to be watered."

Mary led the elephant group. She spotted a watermelon rind off to the side. She made up her mind to march over and get it.

The greenhorn Eldridge had a stick that was supposed to help him control Mary. He poked her on the head to keep her moving, Brown recalled.

"When Mary reached over with her trunk to put that (rind) in her mouth, he took his pick and punched her behind the ear and wouldn't let her have that watermelon skin. She took her trunk and just deliberately reached up, wrapped it around him, brought him out and slammed him down in that gravel road," Brown said.

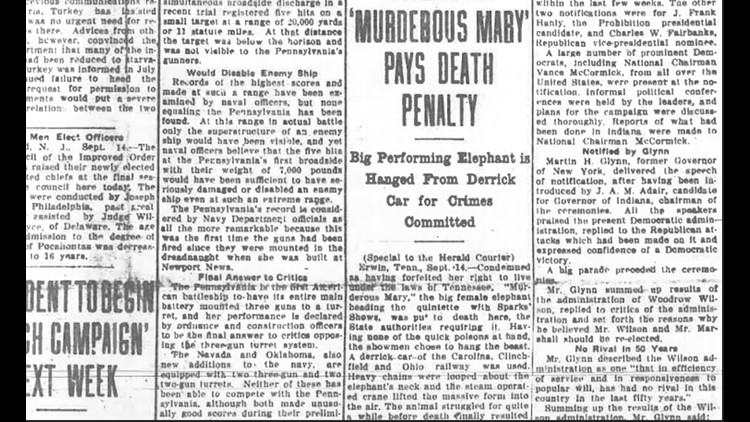

The Bristol Herald Courier ran a front-page story that afternoon with a Kingsport dateline.

The first sentence read: "The mad fury of an elephant when seized with an unwonted thirst for the blood of its keeper, as is sometimes related in fiction, was witnessed here at 4 o'clock this afternoon as a ghastly reality. Walter Eldridge, a Virginia mountaineer, 36 years old, was the victim."

The crowd retreated in horror. They feared she'd go on a rampage.

"It looked like, the best I can remember, that man's body splattered all over that gravel road. She slammed him down there so hard," Brown told WBIR.

Mary calmed down long enough for circus hands to gain control of her.

A blacksmith, hearing all the commotion, stepped out and fired repeatedly with a pistol at her. The bullets had little effect on her tough hide, Price wrote.

Witnesses, having seen a foreign animal suddenly squash the life out of a man, began calling for her death, Brown said.

In two days, Sparks was supposed to be in nearby Johnson City, but that town quickly made it known it wanted nothing to do with a killer elephant.

Charlie Sparks had little choice. He could get rid of Mary or risk financial ruin and permanent bad press.

The show went ahead that night in Kingsport -- with Mary in it, according to Price. It was her last performance.

The next day, Sparks elected to head to Erwin as previously scheduled and string her up by a derrick, or "big hook," used to right wrecked cars. The heavy-duty derrick would meet the circus in the Erwin yard.

They could kill her right there.

The execution of the monster elephant

Sparks circus pulled into Erwin on a soggy Wednesday morning, Sept. 13, 1916. It had rained all night, historian Martha Erwin said.

Much of Sparks’ equipment got mired in mud, according to a 1970 paper by ETSU Professor Thomas G. Burton now kept at the Archives of Appalachia.

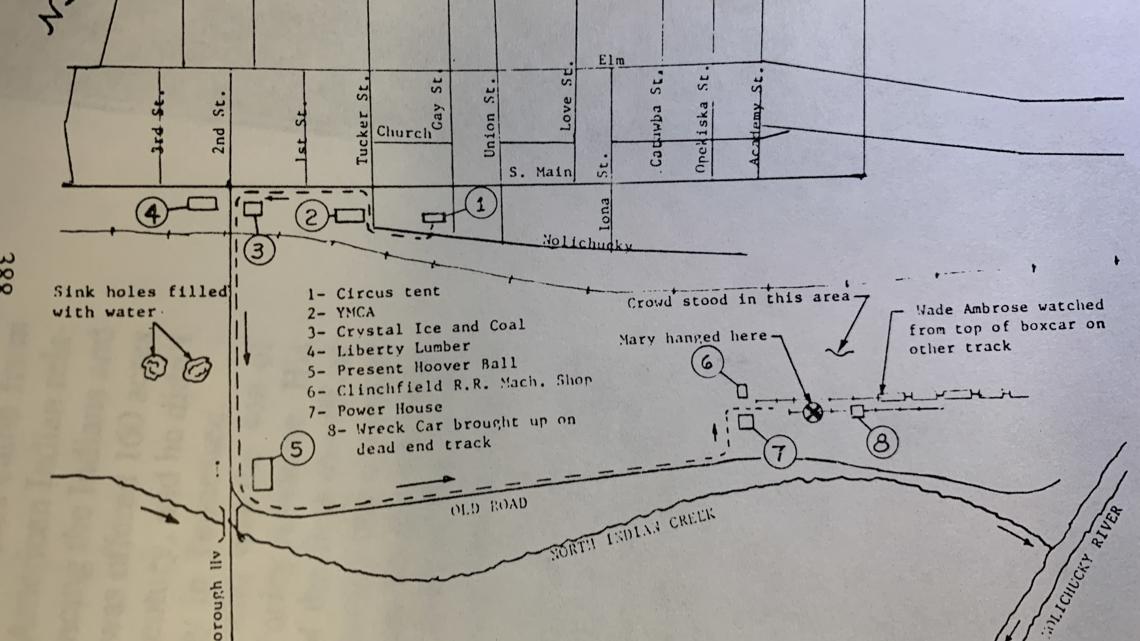

The elephants, Mary included, used their great might to pull the wagons across the swampy yard. The circus set up its tent downtown at Gay Street and Nolichucky Avenue near the railroad tracks.

After putting on a matinee, it was time to kill Mary. A diagram that's now part of the archives details key spots that day.

Mary could tell something was up, witnesses recalled. She acted nervous and suspicious. To get her to go with them, circus personnel walked the rest of the elephant troupe with her down Nolichucky to Second Street, took a left at Liberty Lumber and headed across the yard to a far access point on the western side that ran parallel to North Indian Creek

Hundreds of people fanned out to catch a glimpse of the spectacle.

Lawson Reams, age 6, of Kingsport, watched the procession while perched atop a boxcar. He was visiting an uncle in town and had a prime – and safe – spot to watch.

“They tried to walk the elephant down to the shop area, but she wouldn’t go by herself,” the late Reams recalled years later for WBIR's “Heartland” story.

He added, “I thought it was a great thing to watch.”

Sparks employees led Mary to the big hook and hitched her with a chain. They turned the rest of the elephants around and head back to town. Some trumpeted at Mary, realizing she was no longer with them.

“They had a time getting the chain around the elephant’s neck,” 16-year-old railroad shop employee Guard Banner told Price decades later. He guessed at least 1,500 people were on hand to watch.

Clinchfield fireman Sam “One-Eyed” Harvey agreed to throw the winch that would lift her in the air. The regular winch operator was unavailable that day, according to Price.

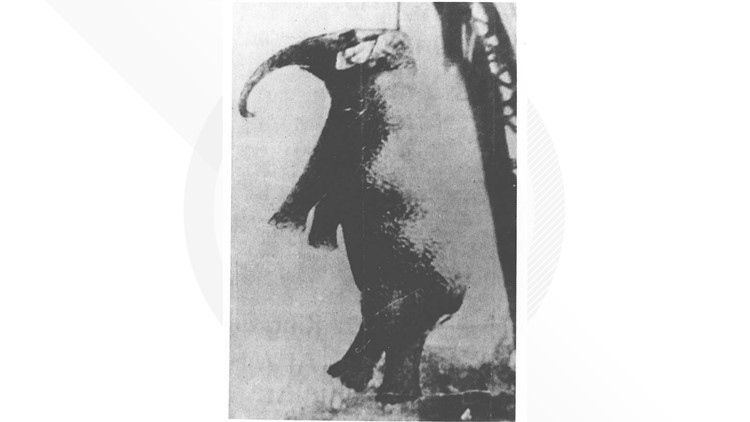

Harvey hit the gears and raised Mary into the gray, gloomy sky. Witnesses would differ on just how high she went – a few feet by some estimates, 8 feet by another – but she didn’t hang long.

The hook in the chain broke, sending Mary plunging to the ground with a thud. She landed on her rear.

“The people really scattered out of the way in a hurry when they saw that elephant fall and hit the ground,” Reams told Landry.

But Mary posed no threat. She’d broken her pelvis; she couldn’t really move, witnesses would recall for Price.

“That kind of stunned it,” Erwin resident Bailey would recall in a late 1960s interview with ETSU’s Burton. That gave the elephant handlers time enough to affix another chain around her neck.

Up went the chain, and this time it held. Her legs kicked a bit as she struggled to survive. Then her body fell still.

After she’d been up there a solid 15 to 30 minutes, Harvey lowered her body to the ground.

Down on one of the lower side tracks, near the roundhouse, the circus people had dug a big grave.

Oldtimers once could find the spot. But with the passage of so many decades, there’s no sure way to tell exactly where it lies.

Clinchfield master mechanic G.F. Shull, Martha Erwin’s great uncle, may offer the best clue. He wrote about the hanging in a letter that appeared in the Knoxville paper a few days after the hanging.

The hanging of Mary the elephant

“She was buried alongside of the powerhouse coal wharf track within a few feet from where she was executed. Her grave was 10 feet by 12 feet by 15 feet,” he wrote.

Some of the Sparks workers cried as they wished the elephant farewell. Others couldn’t bring themselves to watch so they stayed behind at a downtown hotel. Mary had been with them a long time, Shull wrote.

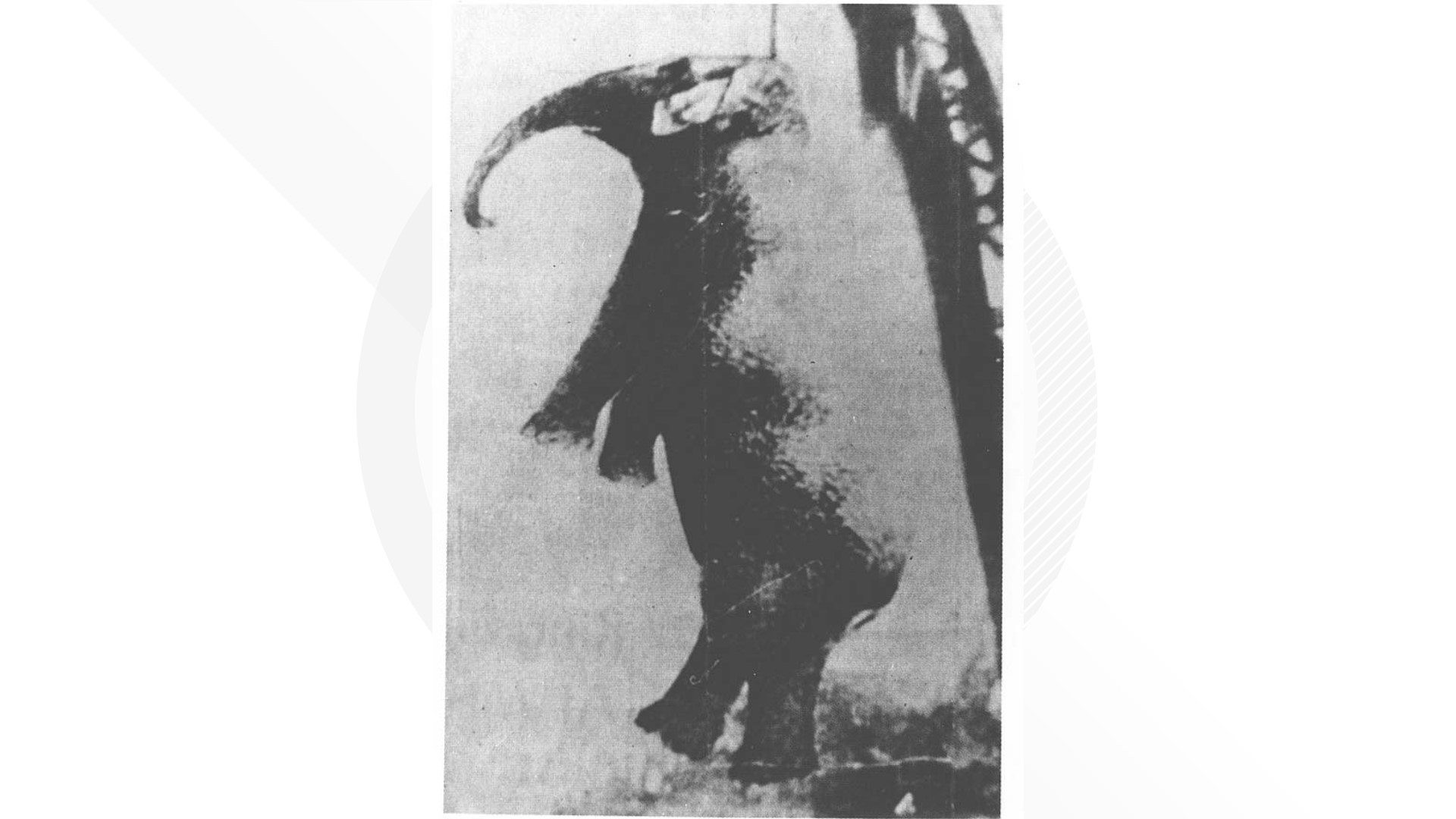

A single photograph exists today that purports to show the hanging. It depicts Mary in the fading light at a high, odd angle, a fact that's always made some suspect it's a fake. Shull wrote that some people tried to take Mary’s photo by the beam of the wrecking derrick's headlight.

The Bristol paper printed for its readers a page 1 story describing the demise of Mary.

"The execution of the monster elephant was witnessed by a throng of mountain people, who will not soon forget it," the newspaper declared.

Erwin Elephant Revival

Convenience, plain and simple, is the reason Erwin gets blamed for the execution of Mary.

Because their big rail yard could accommodate a derrick mighty enough to hang her, they’re remembered as the town that hanged an elephant.

The area has seen a lot of history in its time, including Native American skirmishes and Civil War battles, said Jack Yarber, assistant curator of the Unicoi County museum.

Erwin became famous in the 20th century for its Blue Ridge Pottery, collectibles that remain in high demand across the United State. The idea for the pottery started in Erwin in 1916, the same year Mary died.

Erwin also has given birth to heroes, including Lattie Tipton, who served in World War II with that war's most decorated soldier, Audie Murphy. Tipton died in August 1944 in France while trying with Murphy to charge a German strongpoint.

To Yarber – and other people in Erwin – there's more to the town than the hanging of an elephant.

"There's other things that happened here. But I guess it's a big story,” Yardley said with a resigned chuckle.

Tall tales persist about Mary, including that she’d killed multiple people before Eldridge, and that men dug her back up to salvage her tusks in the rail yard after the hanging.

The story is still told – unverified so far as historians can tell – that Kingsport held a trial and declared she must be put to death after throwing Eldridge to the ground.

Then there’s the yarn that she was the biggest elephant in America, bigger even than Jumbo, the giant African bull owned by P.T. Barnum who ironically died in 1885 after being rammed and killed by a locomotive in St. Thomas, Ontario, Canada.

For decades, Martha Erwin said, people only talked about Mary amongst themselves. You knew better than to discuss it in public, she said.

But the story never died.

In 2016, as the town approached the 100th anniversary of Mary’s death, townspeople decided to turn the story into something positive, said Jamie Rice, the town's communications director.

For four years, they sponsored the “Erwin Elephant Revival,” which featured elephant statues painted in tribute to Mary. The statues were displayed downtown and eventually sold, with the money going for good causes, including to an elephant sanctuary in Hohenwald southwest of Nashville.

When COVID hit in 2020, they could no longer find a statue supplier and the project was put on hold, Rice said. Some statues can still be found around town, in businesses and in people’s yards and homes.

Rice said she’s hopeful that someday they’ll be able to resume the project and raise more money in Mary’s memory.

They’ve raised about $60,000 so far for the elephant sanctuary in Hohenwald, Rice said.

If Mary were alive today, that’s probably where she would have ended up.