KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — Arthur Bohanan can't say how many bodies or fragments of bodies he processed at Ground Zero after the terror attack.

The collapse of the World Trade Center's mammoth twin towers proved so violent the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, that many victims simply were obliterated or became unrecognizable as human beings.

Bohanan saw everything from complete corpses during the labeling and DNA collection process to a right human eyebrow.

The retired Knoxville Police Department criminalistics specialist and his colleague KPD Lt. Steve Tinder knew during the weeks they spent in lower Manhattan, just down the street from the attack, that they had to keep working.

Photos: 15th anniversary of Sept. 11 attacks commemorated at Flight 93 Memorial

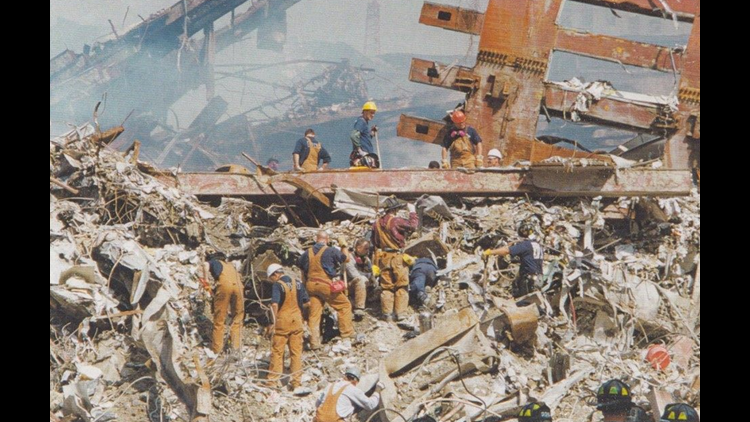

They were among the dozens of people who worked hour after hour, day after day, following Sept. 11 to inspect, inventory and send off for testing every kind of human remain found at the scene to try to confirm the hundreds of victims killed when the hijacked passenger planes hit the WTC.

More than 2,700 people died in the lower Manhattan attack.

Twenty years later, many Americans may assume that every victim has been identified. That's far from the truth.

More than 1,000 people have yet to be formally identified.

Just this week, two victims --- a Hempstead, N.Y., woman and a man whose name was withheld at the request of his family became the 1,646th and 1,647th people whose remains have been identified through “ongoing DNA analysis,” NBC reports.

Bohanan and Tinder say that's just one reason why the United States must never forget what happened that sunny, cloudless morning in Manhattan, at the Pentagon and outside the little town of Shanksville in southwest Pennsylvania.

The men, now 77 and 70, have their own scars from that day. Each has suffered health effects from exposure to the smoke, toxic dust and debris created when the towers came down.

Sept. 11, 2001 attack: Aftermath and cleanup

"You know it took me probably six months to get to the point where I could sleep again," said Bohanan, who has written an autobiography, "Prints of a Man" that includes recollections of his time after Sept. 11. "I still have flashbacks from some of the things I've seen."

Tinder has endured three rounds of cancer. Bohanan has problems breathing sometimes.

"It was a very toxic area," Tinder told WBIR. "And I think most people who got sick, did it by inhalation. You were breathing all this."

DMORT

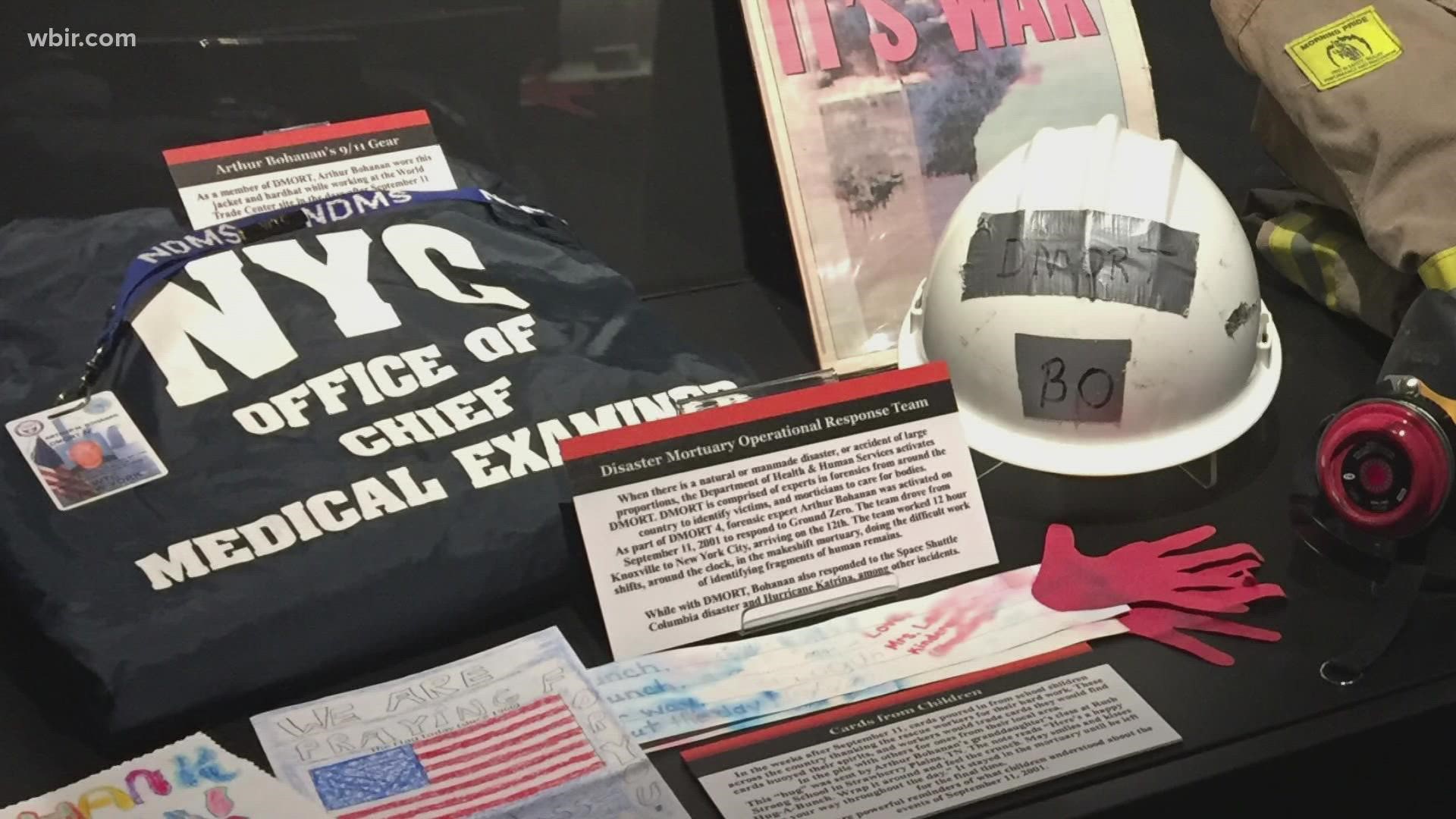

Bohanan and Tinder were among a group of Tennesseans who responded to New York recovery efforts as part of what's called a Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team, or DMORT. Teams typically respond to a large disaster, such as a plane crash, and feature members who are experts in victim identification and mortuary services.

Bohanan had retired from KPD in spring 2001 after years as a crime scene specialist with an internationally recognized expertise in fingerprint recovery. Tinder was a longtime KPD lieutenant with experience in working with the media. Together they'd worked other disasters including a Boeing 747 crash in Guam in 1997 and the aftermath of Hurricane Floyd in 1999.

They were used to seeing trauma, but nothing like what they witnessed as they worked at DMORT centers just yards away from Ground Zero.

They arrived at the scene mere days after the attack itself. Fires burned for days in debris piles.

Bohanan said the extent of the damage was staggering. Chunks of buildings were strewn throughout the neighborhood. Airplane parts from the hijacked jets sat on the street.

"My first time (being there) was at night, walking around in the rubble, and I (saw) a huge red crane slowly going over the rubble trying to find anyone that was living," he said. "It was just – I can't explain what I seen and felt at that time because we knew thousands were dead there."

Part of the 110-story North Tower crashed into the American Express building down below on Vesey Street. Bohanan used to look at what was left of the North Tower and wonder whose remains still were in there.

Smoke rose from the site day after day.

Tinder was awestruck.

"I just could not believe it," he said. "You know, two days, three days prior to that, we were watching it happen on TV -- right where I was standing. And now I'm standing here. I went back to the hotel after that, totally disbelieving what I just experienced."

"My first time was at night, walking around in the rubble, and I (saw) a huge red crane slowly going over the rubble trying to find anyone that was living," Bohanan said. "It was just – I can't explain what I seen and felt at that time because we knew thousands were dead there."

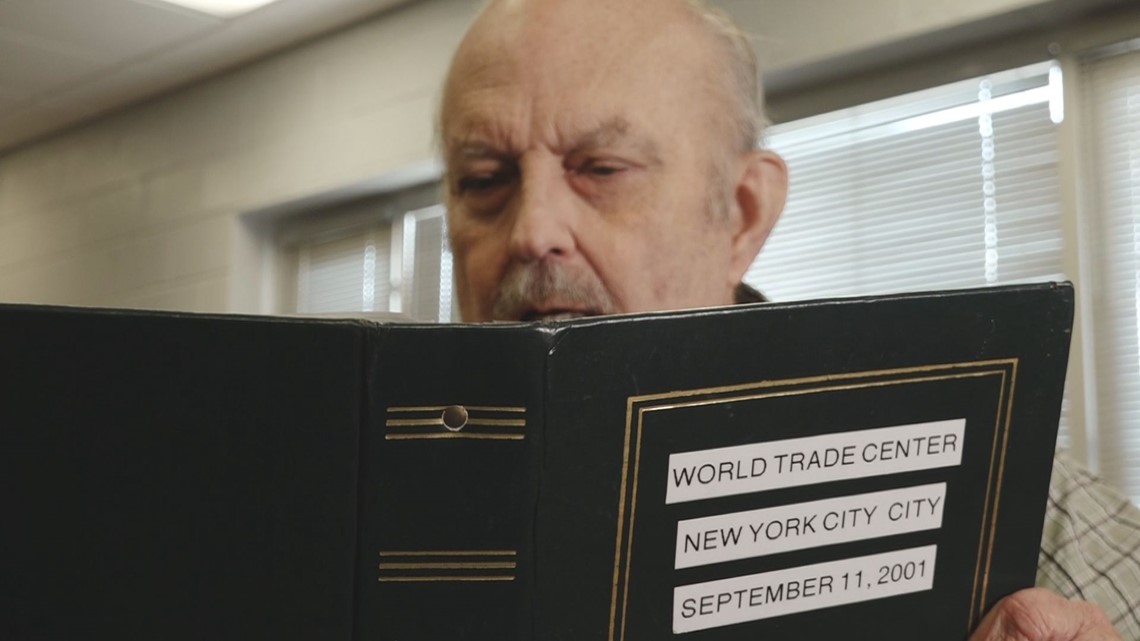

Both men took photos when they weren't working. Their prints, though somewhat faded with time, offer mute evidence of the horrific scene.

The men worked long shifts -- all day and into the night -- as crews found and brought in for processing the human remains. The hope was always that enough would be found to get a DNA sample that would confirm the person's identity.

More than 340 firefighters and 60 law enforcement officers died in the attack doing their jobs. Anytime the remains of a member of service was brought to DMORT, everyone stopped to pay their respects, Bohanan and Tinder said.

Photos: The Tribute in Light for 9/11 terror attacks

"As we worked on the remains, I'd look up and you'd see all these big, burly, strong firefighters or police officers. And I mean, they're just shaking or there was tears pouring down because some of them knew who that was. It was just unbelievable," Tinder said.

Bohanan worked first at a makeshift morgue on Trinity Place before shifting to the Vesey Street morgue, where Tinder worked.

Sometimes if no remains came in, the team would take a break at night, sitting outside in the cool night air.

Often, the winds would shift at night, blowing the smoke from the destruction away from where they worked. Othertimes, the smoke would blow straight into the morgue, Tinder said.

Bohanan spent several weeks in New York before returning home with fellow team member and Knoxville mortuary operator Fred Berry. He'd become sick from breathing the air around Ground Zero. He needed rest and recuperation.

Bohanan wouldn't stay away long, however. He was summoned back to New York after the Nov. 12, 2001, crash of an American Airlines jet in Queens. More DMORT work was needed to identify those victims.

After a few days Bohanan wrapped up time at the Queens plane crash and returned to helping with Sept. 11 remains, this time in DNA recovery through the city's Medical Examiner's Office. He wouldn't come back to Knoxville until early December.

Tinder also spent weeks with DMORT at the Vesey morgue site. Eventually, however, he, too, had to come back to Knoxville and his job as a KPD lieutenant.

Both returned changed men.

'STILL HANGING IN'

Bohanan experienced upper respiratory problems as a result of his work in Manhattan. He and Tinder are among the hundreds of workers who developed maladies now certified as having come from exposure at the attack site.

Tinder retired from KPD a few years later. In early 2007, he came to realize fully how being in New York had damaged his health.

During a routine exam, his doctor spotted what turned out to be breast cancer, which is relatively rare in men. Tinder beat it, but he's since faced two more bouts with the disease.

He's endured round after round after surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. Today, he must contend with COPD and asthma and walks with a cane to help maintain his balance.

"It's just a rough, rough road after three cancers," Tinder said.

But he said he doesn't complain.

"I wish I still had the ability in all that I had many years ago," Tinder said. "There's so many of our fellow DMORTS and firefighters and police officers out of New York that are now deceased. And it's just...you look at it like, I could be like them. And I just don't want to give up yet. So I'm still hanging in."

Twenty years later, all Americans should remember the sacrifices made that day as a result of September 11, Bohanan said. It's something children should be taught now and going forward.

Bohanan himself gives talks to young people to help them understand what happened.

"So many people gave their lives saving others," he said.

At noon and 1:30 p.m. Saturday, Bohanan will speak about his experiences at Ground Zero at the Alcatraz East Crime Museum in Pigeon Forge.

The event, “Forensics at Ground Zero: Disaster Response After September 11th,” will be part of regular admission to the museum.