Reporter's note, Nov. 19, 1:15 p.m. - If the videos embedded within this article do not display on your device, there is a bullet-list at the end of the article with direct links to all five parts of the series and the extra videos of Granville Hunt's full lost-and-found footage.

INTRODUCTION

(WBIR) An old box of unseen film was nearly thrown in the trash. Now it is a historic treasure. Professional archivists call the discovery "a miracle." The films contain pristine color home movies shot in the 1930s and 1940s. These are far from your typical home movies. They were filmed by a trailblazing professional photographer and filmmaker with tremendous skill. The images provide a window in time with scenes of cities, Hollywood stars, the Great Smoky Mountains, marquee sporting events, and historic farms.

WBIR 10News reporter Jim Matheny takes you on a "Hunt for History" to learn about the incredible people and places in the lost films of Granville Hunt.

CHAPTER 1 - TRASH TO HISTORIC TREASURE

In 2016 at his home in Sweetwater, Monty Barger cleaned out the storage shed in his yard. He made a pile for trash and a pile for items to keep. In the trash pile sat a weathered carrying case full of unseen films he bought at a community auction in 1970.

"I bought the box of film at a community auction that was raising money for a park in Philadelphia, Tennessee. I asked the guy who donated it what was on the films. He said it had shots of early-Knoxville, but didn't know much about it. It came with a projector, but I never could get it to work. I put the film in a storage shed and forgot about them. I never did open them again," said Barger.

Barger nearly trashed the film a few times in the decades since he bought it, usually when cleaning out a storage area. On multiple occasions, he placed the box in a throw-away pile and then had a last-second change of heart.

"It has been stored in all types of weather. I didn't know if the film was still any good. Just something in the back of my mind said this will mean something to someone," said Barger.

Through family connections, Barger sent the box of films to me (WBIR reporter Jim Matheny). I then took the box to the archivists at the Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound (TAMIS) to see if the film was viewable.

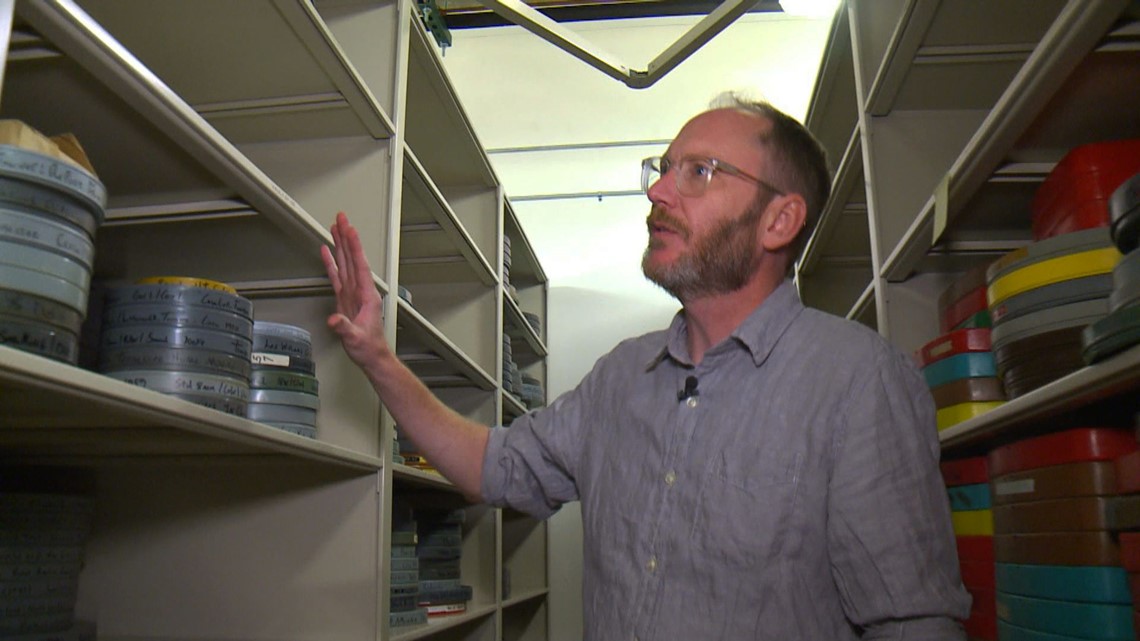

"Man, that is old," said professional archivist Bradley Reeves as he opened the worn case full of metal canisters. "This has been stuck in a can all these years. Usually, materials like this stew in their own juices, decompose, and crumble to the touch. It is 50-50 whether this film will be a pile of dust or usable."

Reeves opened the first metal canister and took a whiff of the film, smelling for the dreaded vinegar odor that accompanies decomposed film.

"That is in mint condition. Look at this label, it says 'Smoky Mountains 1939.' This looks like some really historic footage. These are 16-millimeter films. They are silent home movies and they're in color. People were shooting home movies in color even before Hollywood," said Reeves.

Reeves then opened seven more metal canisters and found all the films in terrific shape.

"I cannot wait to see what is on these films. First, we need to give the film a bath. We use a cleaner and a lubricant that essentially takes off 80 years of gunk," said Reeves.

With the film cleaned and ready to roll, Reeves was unable to contain his excitement as the vibrant color images appeared on the screen.

"Oh, this is beautiful! Look at this! Whoever shot this was clearly a pro. Look at the color and the beautiful composition. This person knew what they were doing. A lot of the amateur footage only lasts a couple of seconds and is really jerky. This was a serious filmmaker with a natural ability," said Reeves.

The reels show images of sporting events, including the 1939 Orange Bowl and the 1939 Kentucky Derby. The scenes shift to the Great Smoky Mountains, a dairy farm, and a mother holding a newborn daughter. The footage rolls and reveals shots of trolleys on Gay Street in Downtown Knoxville. Movie stars emerge from airplanes at the brand new McGhee Tyson Airport in the 1930s. Theaters sell tickets for the new movie "Gone with the Wind" as heavy snow blankets Knoxville in January 1940.

The reels then show off the filmmaker's skill with several minutes of trick photography and stop-motion animations.

"This is incredible. This is someone who really knew how to shoot and have fun with a camera," said Reeves.

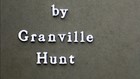

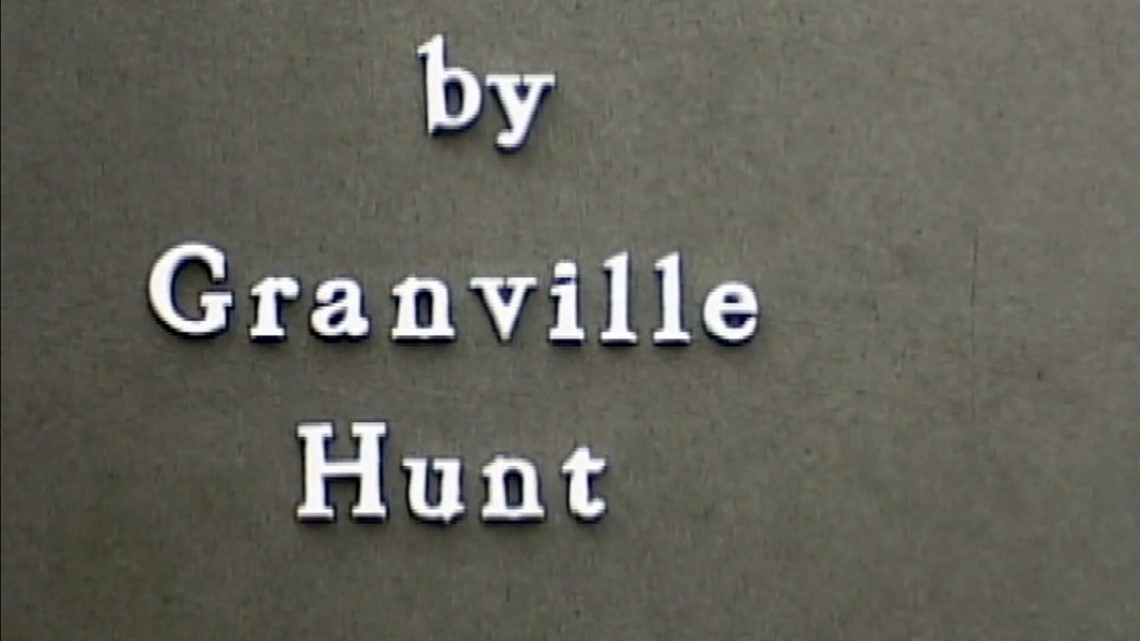

TAMIS receives many home movies that are deemed "orphan" films because there is no way to identify who shot the footage. In this case, the films come complete with a signature. Title screens appear that state the photography is "by Granville Hunt."

"As you can see, we know these were shot by Granville Hunt. Now we begin the research to figure out who this guy was. It's a mystery I love to solve," said Reeves. "This is unique footage and historically valuable. My goodness, you have to consider these are one-of-one. There are no other copies out there. They are home movies, not mass-produced."

We know the name of the photographer. But who was Granville Hunt? How did he become so skilled with a camera? Who are the other people in the films? When and where was this footage shot? What do those places look like today?

LAUNCHING THE "HUNT FOR HISTORY"

Before we delve into all the information discovered about Granville Hunt and this amazing lost-and-found footage, here's some insight into how I chipped away at this "Hunt for History" for a couple of years.

First, the "Find A Grave" website showed Granville Hunt was buried in Loudon County and died Oct. 18, 1963. With a trip to the library to view microfilm copies of the newspaper, you'll find the Knoxville News Sentinel headline "Granville Hunt Dies at Age 54" published on the date of his death.

Hunt's obituary reveals he died from cancer of the esophagus. It also said Hunt was one of Knoxville's first newspaper staff photographers in the 1920s before beginning a 25-year career as a photographer with TVA. There's no more wondering why the home movies look so professional. They were shot by a pro.

The obituary includes other details about Hunt's career with TVA, including an assignment in Chattanooga during World War II that involved "exciting, top-secret work." You also find the name of a wife, Mildred Robinson Hunt, and a daughter, Karen, as surviving relatives in 1963.

In addition to information specifically about Hunt's life, old newspapers and city directories are also invaluable for determining when and where these lost-and-found movies were shot. For example, you see footage of actor Raymond Massey at the McGhee Tyson airport. In June 1939, the Knoxville News Sentinel published an article about Raymond Massey flying to Knoxville to receive an honorary degree from Lincoln Memorial University.

A large visual part of telling the story is shooting photographs from the same angle today as Hunt shot them in the 1930s and 1940s. Photos from the same angle have been juxtaposed with a slider tool for you to compare the scenes of today with the same perspective in the past.

Online Extra: Then-and-now photo comparison slider tool

It is often difficult to identify a shot's location. For example, a shot of a man walking along a city street in 1939 does not resemble anywhere in Knoxville today. If you look up the name of the businesses shown in the background in a 1930s city directory, you learn you're looking at an entire city block that has been torn down and replaced with a parking deck on Walnut Street.

The search also turned up a collection of photographs and writings by Granville Hunt in the Special Collections of the library at the University of Tennessee.

For all the information in libraries and online databases, there is no resource more valuable than talking directly to people. To learn more about these films and the man behind the camera, I conducted interviews with several historians and archivists. I also began an exhaustive search to locate a family member shown in the films.

The end result is we learn Granville Hunt did not just shoot film of history. He was a historic figure himself. Here is the story of the footage and the man behind the camera.

CHAPTER 2 - CAMERAS AND ACTION IN APPALACHIA

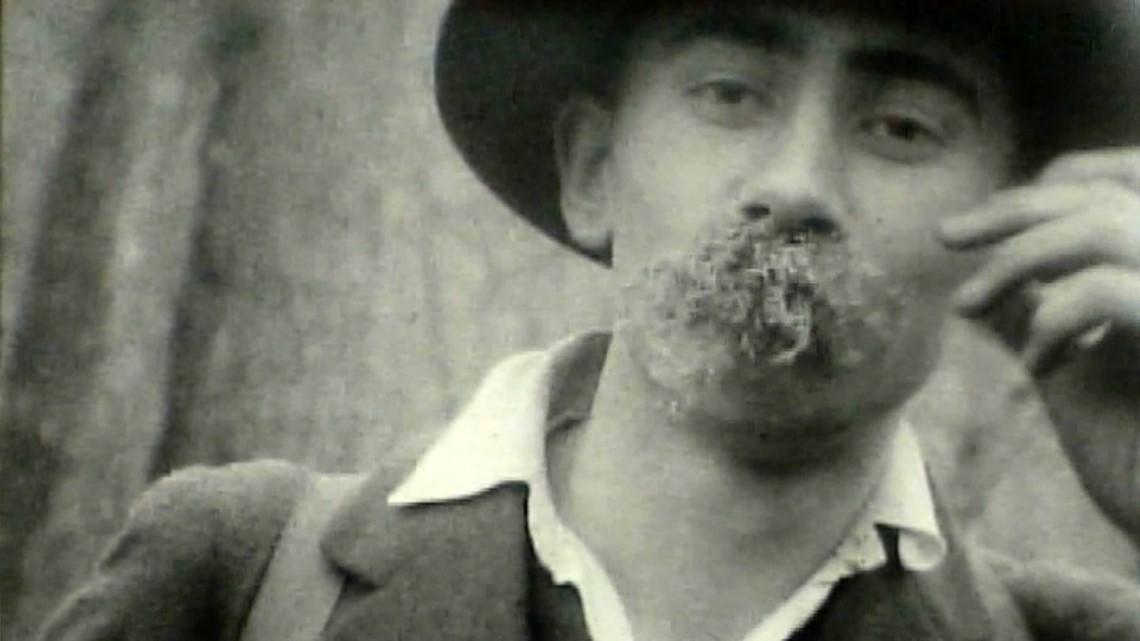

Granville Hunt's parents moved to Knoxville shortly after he was born in Chattanooga. His father, James Hunt, was a commercial artist and sign-maker who enjoyed sharing stories of his wartime adventures as a bugler in Spanish American War.

The apple did not fall far from the tree. Granville Hunt grew up with a flair for drama and art. He also loved sharing stories of current events and embarking on daring adventures.

As a child, Hunt began working as a copy boy for the Knoxville News, the predecessor to the Knoxville News-Sentinel. Hunt's name appears several times in the Knoxville News as a reporter for the weekly kids' edition of the newspaper in 1922.

Hunt also developed a love of the stage and cinema. Early newspaper articles show he acted in plays at Downtown Knoxville theaters. A 1926 article says Hunt was a student at Knoxville High School who wanted to be a movie director.

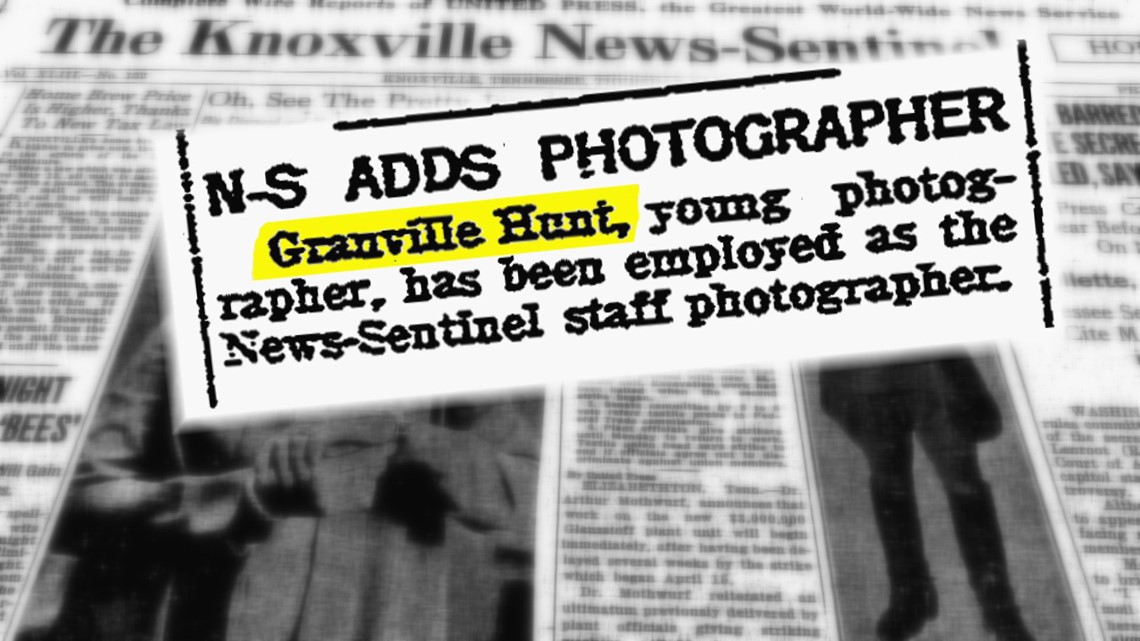

Hunt was a high school student when he began working for the Thompson Co., the premier commercial photography business in Knoxville headed by Jim Thompson. Within a couple of years, Granville Hunt returned to the news business as one of Knoxville's first staff photographers for the Knoxville News Sentinel in May 1929.

"He was a professional photographer for the newspaper for several years and then joined TVA and worked there for 25 years. He had quite a reputation as a photographer," said film archivist Bradley Reeves.

Hunt photographed news, sports, and was a daredevil when it came to capturing dramatic shots for the newspaper. Several captions describe the lengths Granville Hunt went to in order to snap the picture, such as hanging out of the door of an airplane, standing in an area exposed to a dynamite blast, or riding a Studebaker car traveling at the then-incredible speed of 90 miles per hour.

Granville Hunt's name was in the newspaper in the 1920s for more than his daring photography. He was an Eagle Scout and one of the best young hikers in the area. Despite his relative youth, Hunt led treks for the new Smoky Mountain Hiking Club.

A young Hunt can be seen posing and having fun in some of the earliest films of the Smokies shot by Jim Thompson. Photographs and films of the Smokies by Jim Thompson, with help from Granville Hunt, played a major role in gaining public support for the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

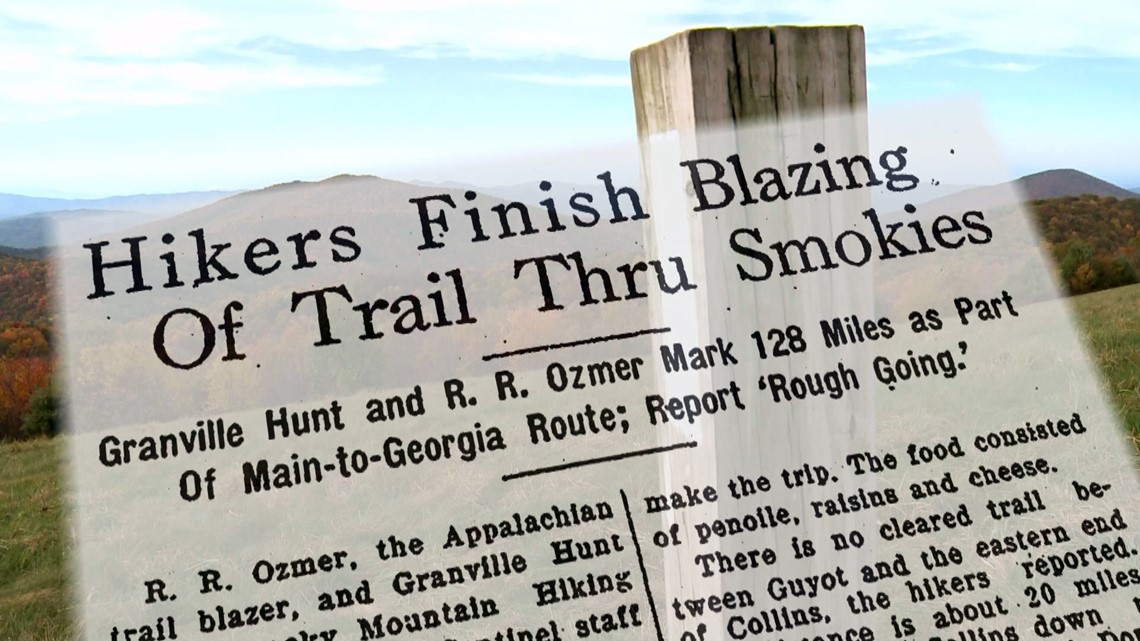

In the summer of 1929, Hunt began marking his path in history. He was appointed by Myron Avery to blaze the new Appalachian Trail through the Great Smoky Mountains. Hunt and Roy Ozmer drudged through the wilderness together along the Tennessee and North Carolina state line for a few weeks to mark 128 miles of the new Maine-to-Georgia route.

"It is Hunt and Ozmer that go through step-by-step in the Smokies to find the actual way the trail will go," said Charles Maynard. "They are carrying a lot of equipment and marking the highest elevations of the entire Appalachian Trail at Clingmans Dome. These places are not easy to reach. There were no trails."

Charles Maynard has written several books on the history of the Great Smoky Mountains and the Appalachian Trail. He served as the first executive director of the non-profit Friends of the Smokies and also serves on the national board of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. He says there are several reasons Hunt was chosen to mark the rugged section of the new Appalachian Trail through the Smokies.

"First of all, Hunt is a very good hiker and he is from this area. He has hiked a lot in the Smokies and knows how to make it for an extended period in the wilderness. The other main thing is both he and Ozmer are young. They were physically able to do the job and they had time to do it. Guys who were just a few years older might have a job and a family to support. Ozmer and Hunt were experts who were also young enough that they could to afford to spend a few weeks in the summer marking the trail," said Maynard.

Several articles appear in the Knoxville News Sentinel in 1929 about Hunt marking the Appalachian Trail. Hunt is also mentioned in the August 1931 issue of Field and Stream magazine in an article written by Roy Ozmer titled, "Blazing the Great Smokey (sic) Trail."

It should be no surprise a large portion of the lost-and-found films of Granville Hunt includes beautiful scenes of the Great Smoky Mountains. One of the reels has more than 12 minutes of amazing color images of the park in 1939, a year before it was officially dedicated. You see classic cars roll through the tunnels on Newfound Gap Road and tourists enjoying the Chimney Tops, Mount LeConte, and The Sinks waterfalls on the Little River.

"I was amazed to see these color movies of the Smokies in its early days as a park. It is almost like time travel. You are getting to look over Granville Hunt's shoulder at a young forest that had been logged instead of the mature forest that we see now. There are views and overlooks you truly cannot see anymore because the forest has grown up. You get so much more of what he experienced by seeing these movies instead of just one snapshot. It is important for us today because without a sense of how we got this [park and trail], you take it for granted like it has always been here," said Maynard.

Extra Video: Granville Hunt's full 1939 footage of the Smokies

There is certainly no shortage of home movies of the Great Smoky Mountains in its infancy. Professional archivist Bradley Reeves says there is more footage of the Smokies than any other location in the collection of home movies at the Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound (TAMIS).

What makes the Granville Hunt footage in 1939 so spectacular and unique is its professional perspective and artistic eye.

"The difference here is the quality. It is shot on 16-millimeter film, which is a higher-quality format than 8-millimeter. The photographer is a professional. He holds the camera for steady shots that last several seconds. The color is stunning. The pictures are composed beautifully. It's a work of art that really captures the beauty of the mountains," said Reeves.

"It's amazing to find this hidden treasure of home movies. You're getting to look over Granville Hunt's shoulder at what he saw," said Maynard. "You get a sense of what he was experiencing. I think people should care because it's a window in time that sets up our time."

CHAPTER 3 - PHOTOJOURNALISM PRODIGY

The adventurous young Granville Hunt from Knoxville made headlines in the summer of 1929 for blazing the Appalachian Trail through the Smokies. Yet, at that point, Hunt was already making the front page of the newspaper for a living.

Hunt was hired in May 1929 as one of the city's first newspaper staff photographers. Hunt joined the staff of the News Sentinel, which was a natural transition after working for years at the paper as a copy boy.

Hunt shot news, sports, and life in East Tennessee at the dawn of the golden age of photojournalism.

"Granville worked at the newspaper and he obviously knew what he was doing. He had great skill and shot a wide variety of subjects," said professional film archivist Bradley Reeves.

Extra Video: Granville Hunt's full Knoxville footage in 1939-1940

The Knoxville News Sentinel archives show Hunt was a prolific photographer with an artistic streak. On multiple occasions, the paper included captions with Hunt's photographs noting they sent him to shoot a disaster and he came back with a postcard.

One caption for a photograph of sunlight glistening on floodwaters in Knoxville said "Hunt has an incorrigible poetic streak" and posed the rhetorical question, "What's a newspaper supposed to do when a photographer brings back a beautiful picture like this other than print it?"

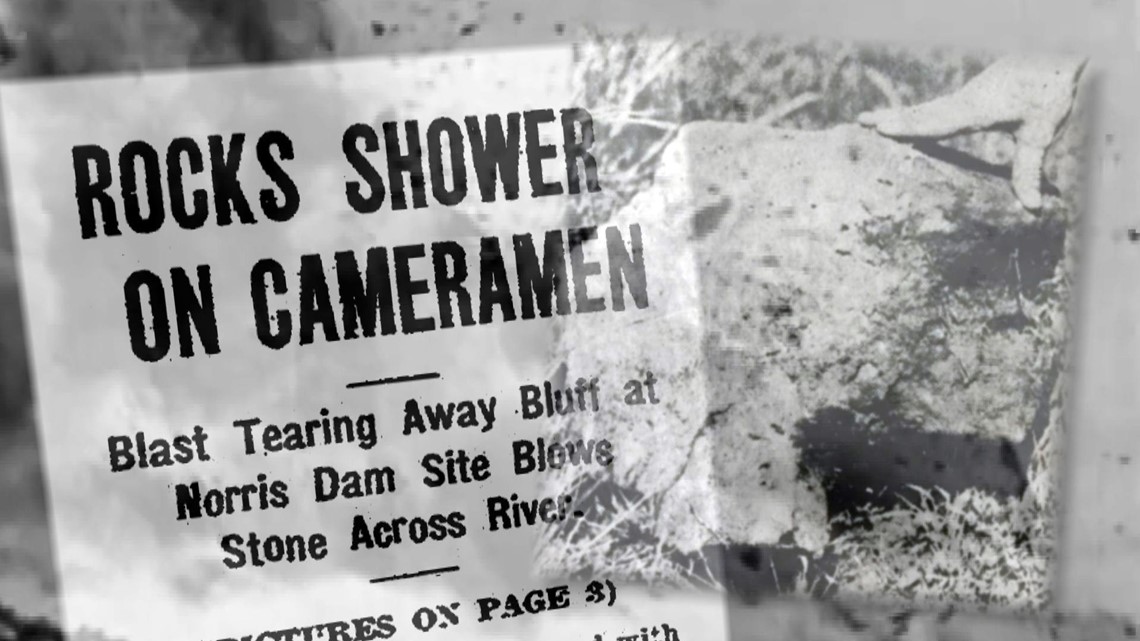

The University of Tennessee's Special Collections has a box of Hunt's photographs and news clippings from the early-1930s. The collection includes a four-page typed story by Hunt about an explosive assignment in September 1933.

"He's working for the Knoxville News Sentinel and goes to cover the first early-stages of construction of Norris Dam," said Pat Ezzell, TVA historian. "The crews are going to blast part of the cliff. The head dynamite guy explains where he [Hunt] needs to stand to be safe, that it's going to be fine, it's going to blow the rock away [in one piece], and that is definitely not what happens."

Instead of tearing away one solid chunk of the cliff, the 400 pounds of dynamite shattered the hillside and sent a shower of boulders and rocks across the river at Granville Hunt. Boulders three-feet wide landed all around him. Some of the large boulders were thrown more than 100 yards beyond where the group of photographers were standing.

A flying rock tore the camera from Hunt's hand as he ran for cover. The debris shredded trees and peppered Hunt with "machine gun fire" of smaller stones.

Hunt wrote the rocks hailed down for "the most thrilling 20 seconds of my life" before the sky began to clear. Hunt's notes say nobody was injured aside from bruised backs.

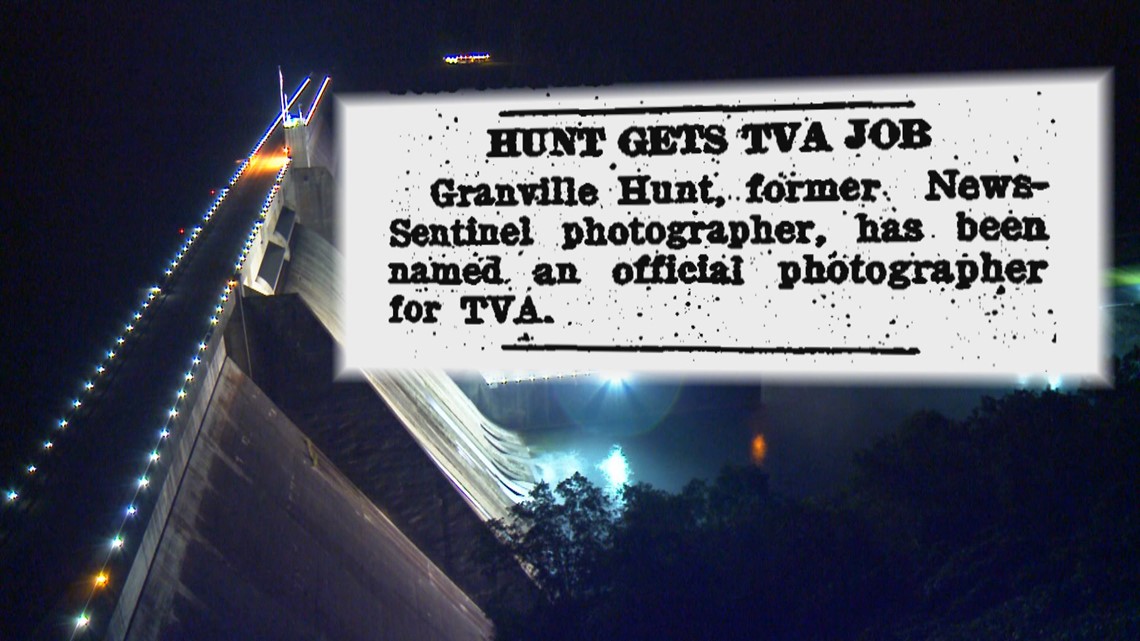

"He published that story in the News Sentinel with his photos. The clincher of the story is shortly thereafter, maybe the end of the week, he became a photographer for TVA," smiled Ezzell.

Hunt landed a job with the brand-new TVA photographic division in October 1933. When the division opened in November 1933, it consisted of Hunt assisting head photographer E.H. Neukon of Ohio and outsourced New York photographer Lewis Hine. The article in the News Sentinel states, "Hunt's job is to take pictures of all the houses and property acquired for the Norris Dam reservoir."

As a TVA photographer, Hunt continued documenting the construction of Norris Dam and all the other projects that tamed the rivers of the valley while delivering a new age of electricity.

"TVA had a staff of photographers and they took amazing photos. They shot everything from the construction pictures of the dams to the quality-of-life cultural pictures that show how hard life was in East Tennessee," said Ezzell.

A Knoxville News Sentinel article in 1934 says Hunt was responsible for photographing more than 4,000 graves that would be relocated before the creation of Norris Dam and Reservoir. The article also says hundreds of people have already applied for jobs as gravediggers before the positions have even been posted.

"People needed a job, they were desperate, and TVA paid well. I think to be a photographer for TVA back then would have to be one of the best jobs around," said Ezzell. "In my mind, I think of those photographers like cowboys. Some of these photos from great heights, I think about the danger and risk these guys were willing to take to get some of these shots."

ABOVE AVERAGE AMATEUR

Hunt's professional skill with a camera comes through in the lost-and-found home movies that were nearly thrown away.

"Mr. Hunt knew what he was doing. You see fade-ins and fade-outs. That is so unusual for an amateur film," said Reeves. "He was using special effects and having fun with a camera."

In 1938, the News Sentinel published articles about the formation of a club for Knoxville's amateur movie photographers. Hunt organized the club and affiliated it with the national Amateur Cinema League.

Hunt may have left the news business, but he never lost his love for capturing current events. When something big happened in news, sports, and weather, he shot it on his home movie camera.

"You see in the film movie stars like Raymond Massey coming to Knoxville. It's really interesting to see the brand new McGhee Tyson Airport," said Reeves.

Massey was a famous actor who was in town in June 1939 to receive an honorary diploma from LMU for his portrayal of Abraham Lincoln. It was quite a day in LMU's history with Massey in attendance and former U.S. President Herbert Hoover delivering the commencement speech.

Sometimes, Hunt captured history merely by shooting film of his friends. The movies include shots of Knoxville's B.F. Henry. He was a groomsman in Hunt's wedding and a reporter for the Knoxville News Sentinel. Henry went on to become the longtime editor of The Washington Post.

The footage also includes shots of News Sentinel photographer Harold Davis as well as TVA photographers Jim McCoy and Sherrill Lakey.

A captivating portion of Hunt's lost-and-found films features shots of Downtown Knoxville during a large snowstorm on January 23, 1940. Deep snow piles up as Hunt shoots scenes of Gay Street, the Tennessee Theatre, and the old Knox County Courthouse. A large marquee advertises tickets for the new movie "Gone with the Wind."

While the near-record snow is the main focus of the footage, archivists are enthralled with the images in the background.

"You have whole city blocks that have been torn down since then. You see the famous Lyric Theater that goes back to the late-1800s. We didn't have any footage of the Lyric. There are lots of missing pieces of the downtown puzzle," said Reeves.

Other shots include streetcars on Gay Street and springtime dogwood blooms in Sequoyah Hills.

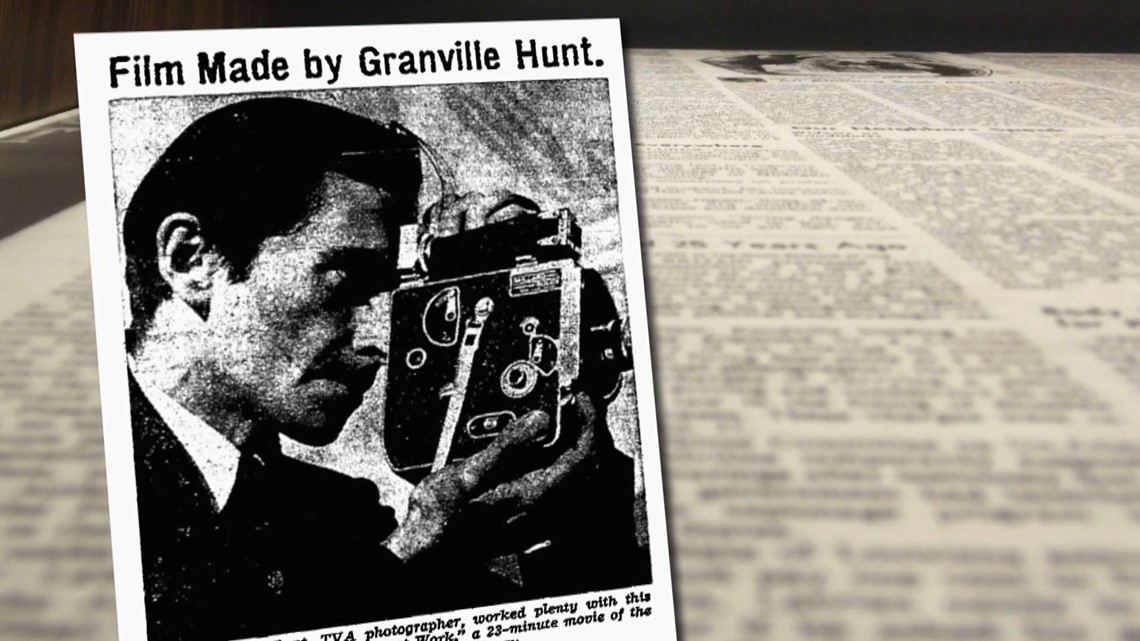

Hunt put his filmmaking abilities to use for the local library and the University of Tennessee. In 1940, an article in the News Sentinel covers Hunt's creation of an educational film titled "Your Library at Work" to highlight the services and resources available at Knoxville's Lawson Library.

In 1941, Hunt shot a film called "Your University at Work" about the University of Tennessee. This was the first official movie UT ever produced. The final product was an 11-minute film showcasing the ways the university benefits the region. An article in the News Sentinel about the film's "world premiere" at the Tennessee Theatre expressed shock because "it does not include a speck of football."

The Knox County Public Library and the University of Tennessee have not been able to locate copies of the films shot by Hunt. This makes the discovery of his lost home movies even more historically-valuable.

SENSATIONAL SPORTS SHOTS

Hunt and his friends clearly loved the news. Hunt also loved sports.

One reel of Hunt's lost-and-found films contains color footage of the Kentucky Derby in May 1939. It is possibly the only known color footage of the 1939 race. It is certainly the only color footage shot by a professional on a 16-millimeter home movie camera from a prime position on the infield rail.

Video Extra: Full 1939 Kentucky Derby film and shot list

The Kentucky Derby is a 1.25-mile race on a 1-mile track. Hunt positioned himself on the home stretch after turn four, allowing him to get up-close shots of the horses at the start of the race and as they round the final turn for the home stretch. The footage shows a horse named Johnstown wearing a bright red mask burst out of the gate, gallop by the camera at the start of the race, then charge around the fourth turn en route to the title at Churchill Downs.

Another reel from the beginning of 1939 seems to be a typical Florida vacation with vibrant color shots from Miami Beach. Then the footage suddenly strikes gridiron gold.

"You find stuff like this that absolutely blows you away," said Reeves. "They are in Miami because the Vols are playing in the Orange Bowl."

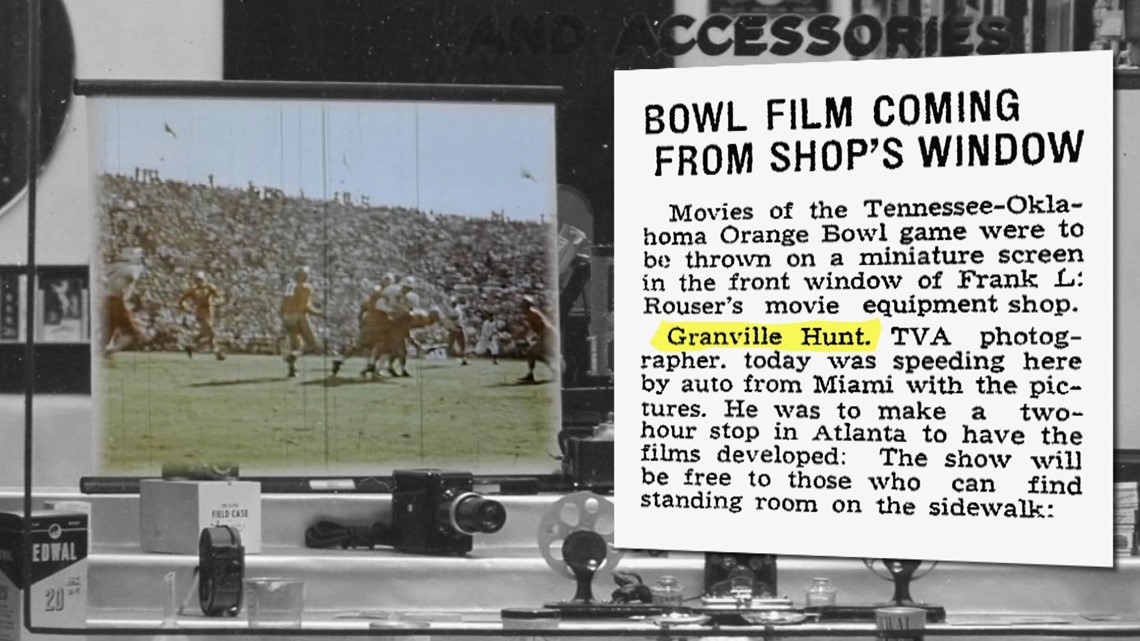

The family has traveled to Miami for the 1939 Orange Bowl where the undefeated Tennessee Vols played the undefeated Oklahoma Sooners. Hunt shot color footage of the game that capped the first national championship season for UT and legendary head football coach Robert Neyland.

"You see General Neyland and the Vols. It's not just the game, but the fans and the stands," said Eric Dawson at TAMIS.

Hunt teamed up with Frank Rouser, the owner of a photo shop in Knoxville, to shoot the game from multiple angles. The two then edited the highlight reels together and played the films in Rouser's storefront window.

"They would film these games, edit them together, and have public screenings. They created artwork and were very clever and creative," said Dawson. "This was long before the days of television. These public screenings were the only way you could see the game if you did not make the trip to Miami."

Hunt provided a window to the world of sports that would have otherwise been unavailable to fans of the Volunteers. Without the miraculous discovery of his lost films, we may have never had this view of history and the adventurous nature of a Knoxville photographer.

"These are incredible shots that nobody else has. You're never going to see anything quite like this again," said Dawson.

To briefly recap, a lost box of film not only turns out to have incredible footage of Knoxville, the Smokies, and landmark moments in sports history. The footage was shot by one of the first professional news photographers in Knoxville history who also happens to be the guy who blazed the Appalachian Trail through the Great Smoky Mountains. And we still have not told you about Hunt's role in World War 2 or his amazing family.

CHAPTER 4 - LIKE FATHER, LIKE DAUGHTER

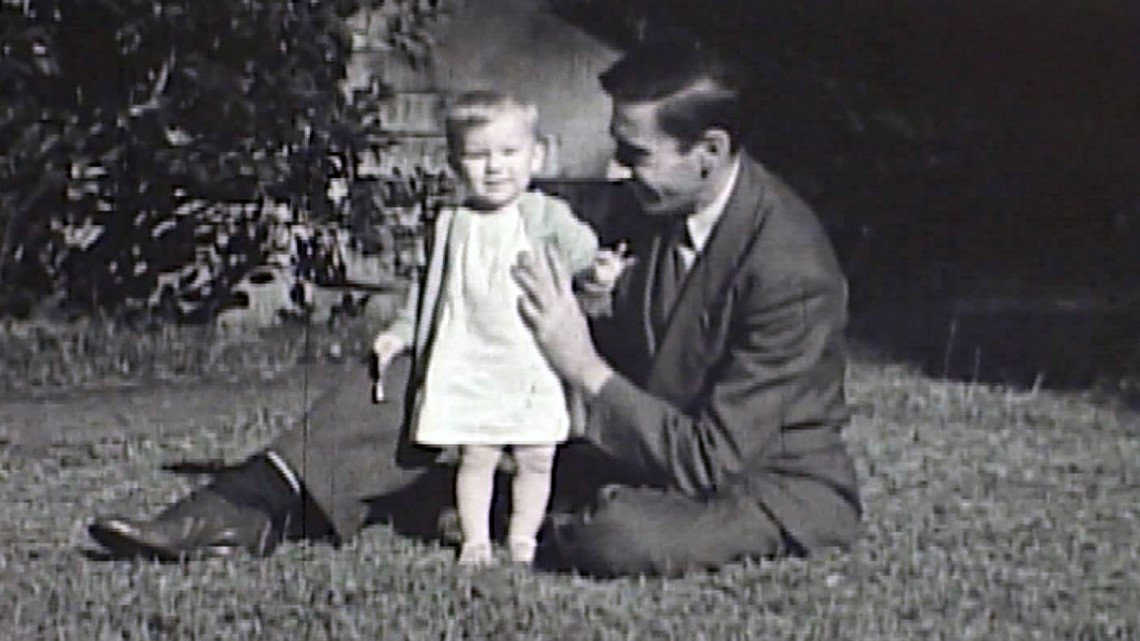

Several reels of Granville Hunt's rediscovered home movies show the life of his daughter, Karen Robinson Hunt, from a newborn in 1945 through her first birthday party in 1946.

After searching obituaries, marriage records, newspaper articles, and other databases, I located the woman who appeared in the films as an energetic infant. Karen Robinson Hunt Hackney now lives in Bowling Green, Kentucky, where she is a retired professor of physics and astronomy professor at Western Kentucky University. Hackney and her late-husband both served as the head of the NASA Consortium for the state of Kentucky.

"My father was Granville Hunt and my mother was Mildred Robinson Hunt. Her friends called her Mickey or Mick. You see these films show the Robinson family farm and cabin near Loudon. On that farm, my father would show me the constellations and say he was sure everyone had a star up there," said Hackney.

The lost films show Granville, Mickey Hunt, and her parents designing and building a log cabin near Robinson's Mill in 1940. When Granville's father-in-law, Carl Robinson, retired from a long career as a railroad machinist in 1946, he and his wife spent their summers at the cabin on the farm.

"I spent my summers at the farm, too. You see in those films, farming in those days was difficult. We had to plow some areas with mules. During those summers, my father would drive back and forth from the farm to his job at TVA in Chattanooga. Some of my proudest memories were when he flew over the farm to photograph the TVA transmission lines. He would get the pilot to circle and we would wave at him while he was hanging out of that airplane with his camera," smiled Hackney.

Hackney said her father was adventurous and took her mother along for the ride. Granville proposed marriage after taking Mickey up in an airplane in 1934.

"There was no way she could say no at that point," laughed Hackney. "He liked airplanes and flying."

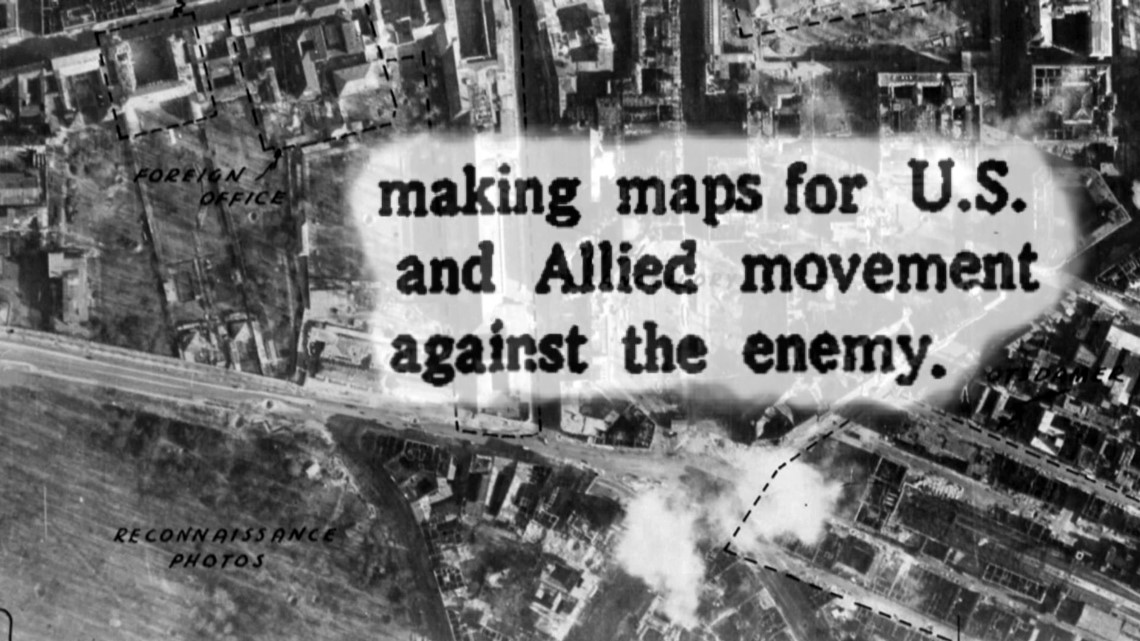

Granville Hunt had access to airplanes as a photographer for TVA. Hunt had a knack for working with aerial photography that developed into a new role during World War 2. TVA transferred Hunt to Chattanooga for "exciting, top-secret work" making aerial maps for the military of enemy territories and troop movements.

"TVA made a tremendous amount of contributions during World War 2. A lot of people are not aware we had the maps and surveys unit in Chattanooga," said TVA historian Pat Ezzell. "The work they did there was so secretive, the only photos we have of the operation were taken after the war. They re-created some of the work for photos after the war, but never allowed cameras when it was actually taking place."

"Reconnaissance would send all the aerial pictures they took over enemy territory to Chattanooga. They would develop these huge prints that were then converted to maps and sent back to the war in Europe and the Pacific," said Hackney.

Hunt toured several government photo facilities and wrote the guidelines for how TVA developed photography for the large military maps.

For an adventurous person like Granville Hunt, there were mixed feelings about serving his country in an office in Chattanooga while his friends went overseas to fight. Hunt was in his 30s and physically able to fight. He was also an expert outdoorsman who blazed the Appalachian Trail. More than once, he tried to leave TVA and enlist for combat.

"He would get on the bus and head to Fort Oglethorpe. The military never would take him because they said, 'You have to go back and keep doing your job.' The job that he was doing was so vital and there was not time to get anybody in and trained his level," said Hackney.

Hunt fought for his country as hard as he could from home. His team at TVA mapped more than 500,000 miles of enemy territory to provide crucial intelligence to the U.S. and Allied forces.

"Think about half a million miles of foreign territory. That is tedious work you're doing and it required expertise," said Ezzell.

"One of the impressive things about my dad was the work ethic he had. During the war, that important task that TVA had to do, he really worked tirelessly," said Hackney.

Hunt's lost-and-found films show some of his TVA coworkers in Chattanooga. As usual, he is having fun with the camera and performing trick-photography to entertain his colleagues.

"One of the things I remember about my father is everybody liked him. He never met a stranger and people liked him, which was a wonderful quality. He also cared so much about his work. He was someone who really liked cutting-edge technology and learning how things worked," said Hackney. "That is what I love in these films when you see my parents and grandparents designing that cabin and then doing the work. He instilled that in me. As soon as I was old enough to lift something, I was helping him carry photography equipment and take pictures."

PARALLEL UNIVERSE

Hunt encouraged his daughter to learn how things worked. He was also supportive as she pursued an education in scientific fields traditionally dominated by men. her education in the fields of science that were dominated by men.

"My parents were always very encouraging and helped me learn science and math. I was one of only three female students in the physics department at the University of Tennessee," said Hackney.

Karen says she missed her first physics exam as a freshman at UT to attend her father's funeral. Cancer of the esophagus killed Hunt on Oct. 18, 1963, at the age of 54.

"My husband and I both went to Fulton High School and then to the University of Tennessee. My father gave Richard [Hackney] the assignment of researching everything he could about the cobalt cancer treatments," said Hackney. "It was a very sad situation because we knew his condition was not something he could live through."

Granville Hunt is buried at Roberson Cemetery in Loudon County beside his wife. Mildred Robinson Hunt died in 1993. The Hunts are buried next to the graves of Mildred's parents, Carl and Laura Robinson.

Karen Robinson Hunt married fellow physics and astronomy student Richard Hackney in 1967. Both graduated from the University of Tennessee, pursued doctoral studies at the University of Florida, and were hired as professors at Western Kentucky University in the early 1970s. A Louisville Courier-Journal newspaper headline in 1978 reads, "Husband-wife team is studying quasar for clues to the origin of the universe."

"Our first grant was with the International Ultraviolet Explorer Satellite. It was a learning experience for NASA and the space telescope. We studied active galactic nuclei, quasars, and the light that would not split into a spectrum," said Hackney.

CHAPTER 5 - A PRESENT FROM PAST TO FUTURE

Capturing light on film was Granville Hunt's profession and passion. The little girl who helped her father take pictures grew up to capture light from the depths of the universe. As an astronomer, Karen Hunt Hackney recorded the light created billions of years ago as it finally reached our eyes in the present after a journey across the universe.

"I like extremes. Certainly, the Universe is as extreme as you can get for a laboratory. I also like thinking about the future. That's why I loved working with students. They are our future," said Hackney.

The light captured on film by Hackney's father in the 1930s and 1940s has finally reached our eyes in the present. A lost-and-found box of Granville Hunt's home movies may feel like a gift from the galaxy with reels of 16-millimeter windows to the past.

Hackney says her father's lost films are especially meaningful because she lost many photographs in a house fire in 2011. But the films serve as more than personal nostalgia. The gift from the past to the present is precious to Hackney for what it means to the future.

"What I have enjoyed is how happy my son, Andy, is to see these films. He obviously never knew his granddad. He and his wife, Odette, live in Australia and I have two beautiful young grandchildren. My son has enjoyed seeing my dad playing with me the same way he does with his children. I'm also looking at this through the eyes of my granddaughter, Olivia, and grandson, Leo, and maybe their children someday. I like to think about the future. This is something people will enjoy seeing in the future," said Hackney.

The film itself is historic. So is the photographer. Granville Hunt made history. He blazed the Appalachian Trail through the Great Smoky Mountains. He became one of the first newspaper staff photographers in Knoxville at the dawn of the golden age of photojournalism. Hunt joined the brand new Tennessee Valley Authority as a photographer and documented the beginning of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. He shot color sports footage and shared it at public screenings, providing a rare glimpse of games for fans in Knoxville before the days of television. During World War 2, Hunt was part of the top-secret team that used reconnaissance photos to create massive maps to provide military intelligence of foreign terrain and troop movements.

Hackney says despite her father's long list of groundbreaking accomplishments, he would shy away from the well-deserved title of "historic figure."

"I think he would laugh about that and say. He would say that he wasn't. I know journalists like to say they don't want to be the story. But you are reporting, photographing, and videoing history. When history comes, they are going to be part of it," said Hackney. "I would think people might enjoy seeing how Knoxville looked back then, regardless of who took the pictures."

SERENDIPITY IN SWEETWATER

Granville Hunt is buried just a few miles from the historic Robinson Mill and family farm featured in some of his color home movies from the 1930s. The cemetery and the farm are only a few miles from a storage shed in Monty Barger's back yard in Sweetwater.

Barger stored the film for 46 years without watching it. He bought the box of film at a community auction in 1970, but could not get the projector to work. Now the box of film he nearly threw away is a historic treasure.

"I am amazed. I would not have dreamed the film would turn out like this. The quality of the film is incredible, plus all the pictures of Knoxville, the Orange Bowl, Robinson's Mill, the family building a log cabin. Just amazing," said Barger. "Mr. Hunt was ahead of his time. The details and the work that went into this film, you can see it. I hope his daughter and family will enjoy seeing this as much as I have. I'm sure they will enjoy it even more because it is their family history. This is something that is all of our history, seeing how times have changed. Being able to look back and preserve that means a lot."

Barger reiterated how close he came to tossing the box of film in the trash.

"A couple of different times, we would be cleaning out a storage area and I'd set it over there in a throw-away pile. By the time we got through, it would always end up in the keeper-pile. How I ended up with something like this, I have no idea. I'm just so thankful I didn't throw it away," said Barger.

The man who donated the box of film to the community auction, Bud Barr of Philadelphia, died in 2001. We will never know the exact path the films took from Hunt to Barr to Barger. One possible connection is Barr likely knew the Robinsons because they all owned dairy farms in Loudon County.

An even greater mystery is how the film survived the sweltering heat and freezing cold of a storage shed.

"It is a miracle, one, that they were shot. Two, that they survived. And three, that they were able to make their way into the archive," said Bradley Reeves, a professional film archivist who founded the Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound (TAMIS). "Think about how meaningful this footage will be to future researchers. People are going to be able to see what Knoxville and these other places were like in a way they never would have without these films."

"It's a view we never would have had without Hunt's skill and his willingness to go into the Smokies and open up the area," said Charles Maynard.

"I think when we make a discovery like this, it gives us all a greater sense of community," said TVA historian Pat Ezzell. "Whether you're new to Knoxville or you've lived here all your life, this is all of our history. This is something none of us have seen before. It belongs to all of us."

The shots by Granville Hunt are now a priceless cultural record from the 1930s and 1940s. The additional research into the story behind the films reveals the story of a talented trailblazer who made capturing light on film his personal and professional passion.

PRESERVING HUNT'S FILMS... AND YOURS

Barger was given free digital copies of the film because he donated the originals to TAMIS. The film has been cleaned, placed in archival cans that allow it to breathe, and stored in a cold vault in the basement of the East Tennessee History Center.

"We keep the film in a cold storage vault where we can control the temperature and humidity. Once they are stored in here, it slows down the deterioration process. They should be good for hundreds of years," said TAMIS archivist Eric Dawson.

Dawson says the clock is ticking for many home movies from the era of 8-millimeter and 16-millimeter film. He says TAMIS wants to help preserve old images and audio recordings.

"People have old home movies stored in places where the films are decomposing. We want you to bring us those movies, we'll archive them, and give you digital copies for free. Then those films are preserved for the future and can be used by researchers and production houses in the future," said Dawson.

One caveat to the TAMIS offer for free digital copies is the footage or the photographer needs to have a connection to East Tennessee. For film that may not be relevant to a regional historical record, you can pay a private archival service to preserve your family films. Bradley Reeves, the founder of TAMIS who originally digitized Granville Hunt's lost films, provides private archival services through his Cinegraphic Archives and Preservation business.

FULL VIDEOS AND EXTRAS

Below are links to full extended clips of Granville Hunt's lost-and-found footage, complete with shot logs that list the time of each shot with a description. The extras also include a then-and-now photo slider comparison tool with photographs taken in 2018 from the same angle as Hunt's footage in the 1930s and 1940s.

- Video Hunt for History Part 1: Trash to Treasure

- Video Hunt for History Part 2: Adventure in Appalachia

- Video Hunt for History Part 3: Photojournalism Prodigy

- Video Hunt for History Part 4: Like Father, Like Daughter

- Video Hunt for History Part 5: A Present from Past to Future

- Extra: Then-and-now photo comparison slider tool

- Extra: 1939 Great Smoky Mountains film and shot list

- Extra: 1939-1940 Downtown Knoxville film and shot list

- Extra: 1939 Orange Bowl film and shot list

- Extra: 1939 Kentucky Derby film and shot list

- Extra: 1939-46 Robinson Mill farming film and shot list

- Extra: 1940 Log cabin construction and shot list

- Extra: 1943 Chattanooga TVA film and shot list

- Extra: 1945-46 Daughter's first year film and shot list