Note: This article is part 5 of the 10News series (link) Hunt for History: The lost films of Granville Hunt.

(WBIR) At Western Kentucky University, retired physics and astronomy professor Karen Hunt Hackney studied the stars. Some of her research focused on quasars, watching the light created billions of years ago finally reach our eyes in the present after a journey across the universe.

"I like extremes. Certainly, the Universe is as extreme as you can get for a laboratory. I also like thinking about the future. That's why I love working with students. They are our future."

The light captured on film by Hackney's father in the 1930s and 1940s has finally reached our eyes in the present. A lost-and-found box of Granville Hunt's home movies may feel like a gift from the galaxy with reels of 16-millimeter windows to the past.

The film itself is historic. So is the photographer. Granville Hunt made history. He blazed the Appalachian Trail through the Great Smoky Mountains. He became one of the first newspaper staff photographers in Knoxville at the dawn of the golden age of photojournalism. Hunt joined the brand new Tennessee Valley Authority as a photographer and documented the beginning of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. He shot color sports footage and shared it at public screenings, providing a rare glimpse of games for fans in Knoxville before the days of television. During World War 2, Hunt was part of the top-secret team that used reconnaissance photos to create massive maps to provide military intelligence of foreign terrain and troop movements.

Hackney says despite her father's long list of groundbreaking accomplishments, he would shy away from the well-deserved title of "historic figure."

"I think he would laugh about that and say. He would say that he wasn't," said Hackney. "I know journalists like to say they don't want to be the story. But you are reporting, photographing, and videoing history. When history comes, they are going to be part of it."

Esophageal cancer killed Granville Hunt at the age of 54. He's buried beside his wife, Mildred "Mickey" Robinson Hunt, who died in 1993. They are buried next to Mildred's parents, Carl and Laura Robinson. All can be found just a few miles from the historic Robinson's Mill and family farm featured in some of Hunt's color footage from the 1930s.

The cemetery and the farm are also only a few miles from a storage shed in Monty Barger's back yard in Sweetwater. Barger stored the film for 46 years without watching it. He bought the box of film at a community auction in 1970, but could not get the projector to work. Now the box of film he nearly threw away is a historic treasure.

"I am amazed. I would not have dreamed the film would turn out like this. The quality of the film is incredible, plus all the pictures of Knoxville, the Orange Bowl, Robinson's Mill, the family building a log cabin. Just amazing," said Barger. "Mr. Hunt was ahead of his time. The details and the work that went into this film, you can see it. I hope his daughter and family will enjoy seeing this as much as I have. I'm sure they will enjoy it even more because it is their family history. This is something that is all of our history, seeing how times have changed. Being able to look back and preserve that means a lot."

Barger reiterated how close he came to tossing the box of film in the trash.

"A couple of different times, we would be cleaning out a storage area and I'd set it over there in a throw-away pile. By the time we got through, it would always end up in the keeper-pile. How I ended up with something like this, I have no idea. I'm just so thankful I didn't throw it away," said Barger.

The man who donated the box of film to the community auction, Bud Barr of Philadelphia, died in 2001. We will never know the exact path the films took from Hunt to Barr to Barger. One possible connection is Barr likely knew the Robinsons because they all owned dairy farms in Loudon County.

An even greater mystery is how the film survived the sweltering heat and freezing cold of a storage shed.

"It is a miracle, number one, that they were shot. Two, that they survived. And three, that they were able to make their way into the archive," said Bradley Reeves, a professional film archivist who founded the Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound (TAMIS).

Barger was given free digital copies of the film because he donated the original film to TAMIS. The film has been cleaned, placed in archival cans that allow it to breathe, and placed in a cold storage vault in the basement of the East Tennessee History Center.

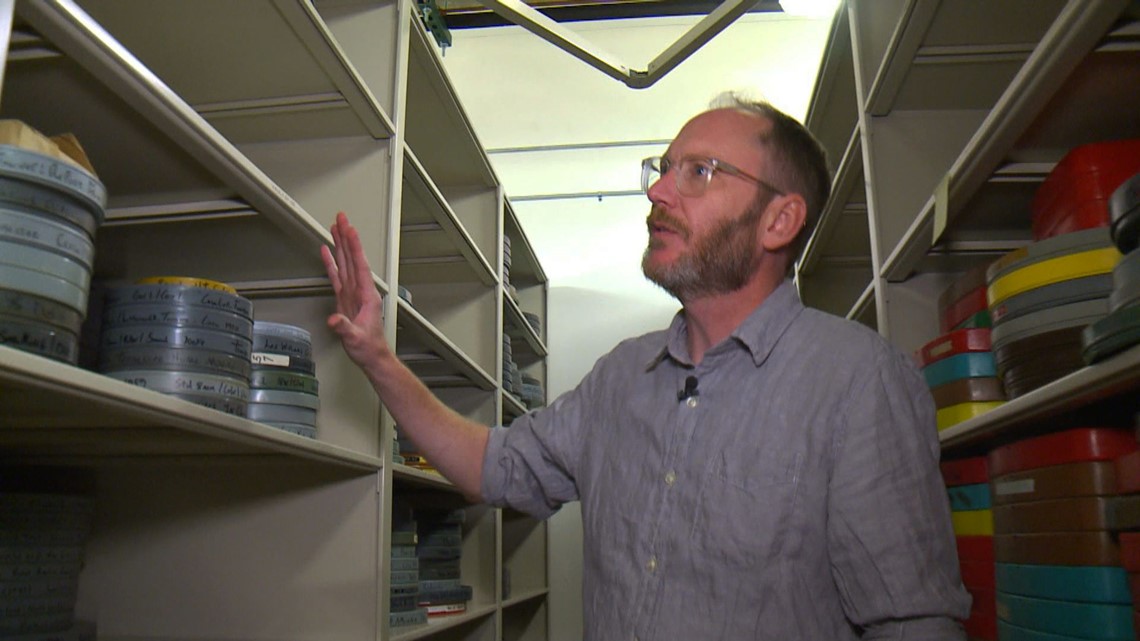

"We keep the film in a cold vault where we can control the temperature and humidity. Once they are stored in here, it slows down the deterioration process. They should be good for hundreds of years," said TAMIS archivist Eric Dawson.

The shots by Granville Hunt are now a priceless cultural record from the 1930s and 1940s. The additional research into the story behind the films reveals the story of a talented trailblazer who made capturing light on film his personal and professional passion.

"I would think people might enjoy seeing how Knoxville looked back then, regardless of who took the pictures," said Hackney. "It does mean so much to me and my family. One positive response has been how happy my son was to see the movies. His grandfather died long before he was born. He knew his grandmother and loved seeing her, too," said Hackney.

Much like her passion for staring at the stars, Hackney keeps her focus on the future when viewing the films from the past.

"I look at it through the eyes of my granddaughter, Olivia, and my grandson, Leo, And, who knows, maybe their children and grandchildren someday. I like to think about the future. This is something people will enjoy seeing in the future," said Hackney.

PRESERVE YOUR FILMS

Dawson says the clock is ticking for many home movies from the era of 8-millimeter and 16-millimeter film. He says TAMIS wants to help preserve old images and audio recordings.

"People have old home movies stored in places where the films are decomposing. We want you to bring us those movies, we'll archive them, and give you digital copies for free. Then those films are preserved for the future and can be used by researchers and production houses in the future," said Dawson.

One caveat to the TAMIS offer for free digital copies is the footage or the photographer needs to have a connection to East Tennessee. For film that may not be relevant to a regional historical record, you can pay a private archival service to preserve your family films. Bradley Reeves, the founder of TAMIS who originally digitized Granville Hunt's lost films, provides private archival services through his Cinegraphic Archives and Preservation business.