Knoxville — Knoxville's oldest black cemetery sits hidden in scrub and brush so thick neighbors can't see it from the road.

The overgrowth is so dense, in fact, that many who live near the 5,000-6,000 graves off Fuller Avenue in East Knoxville don't even know it's there. Anyone who tries to push their way in must confront spiders, snakes and ticks.

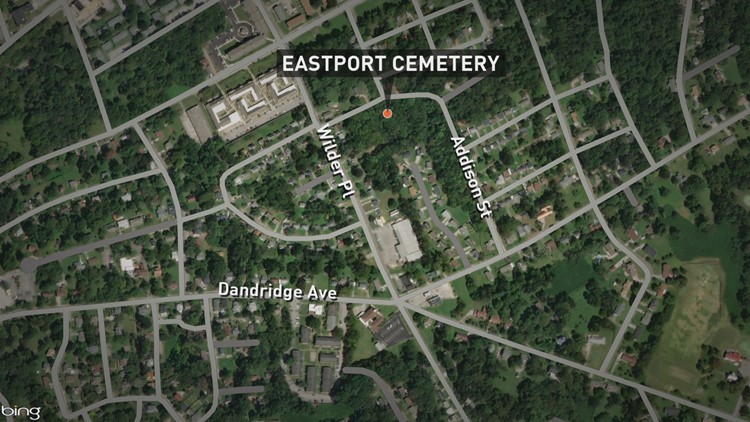

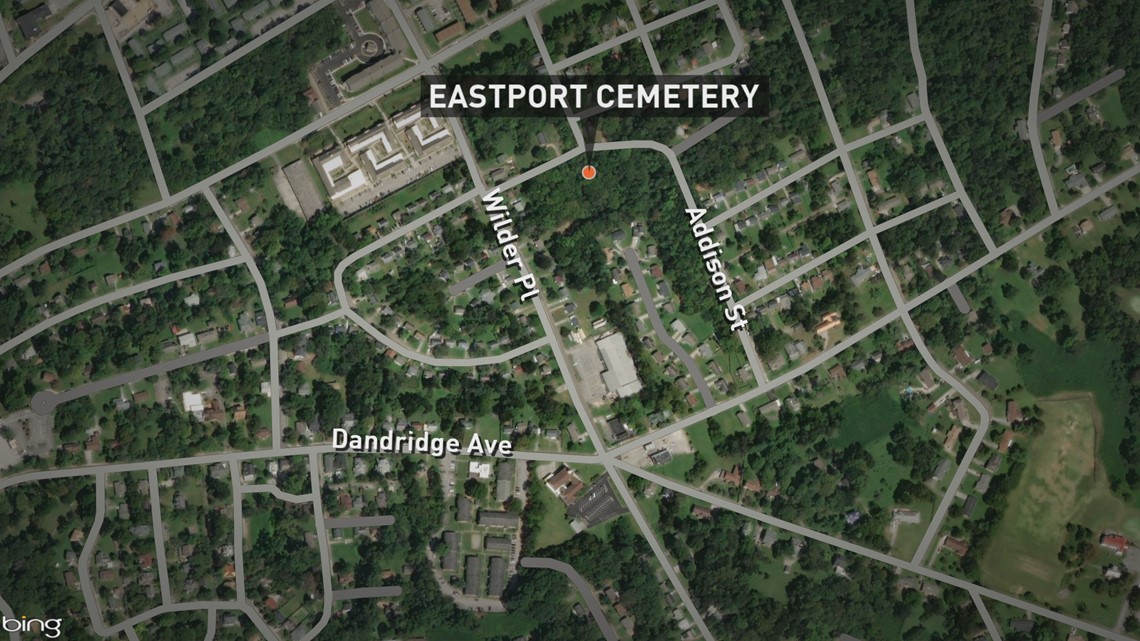

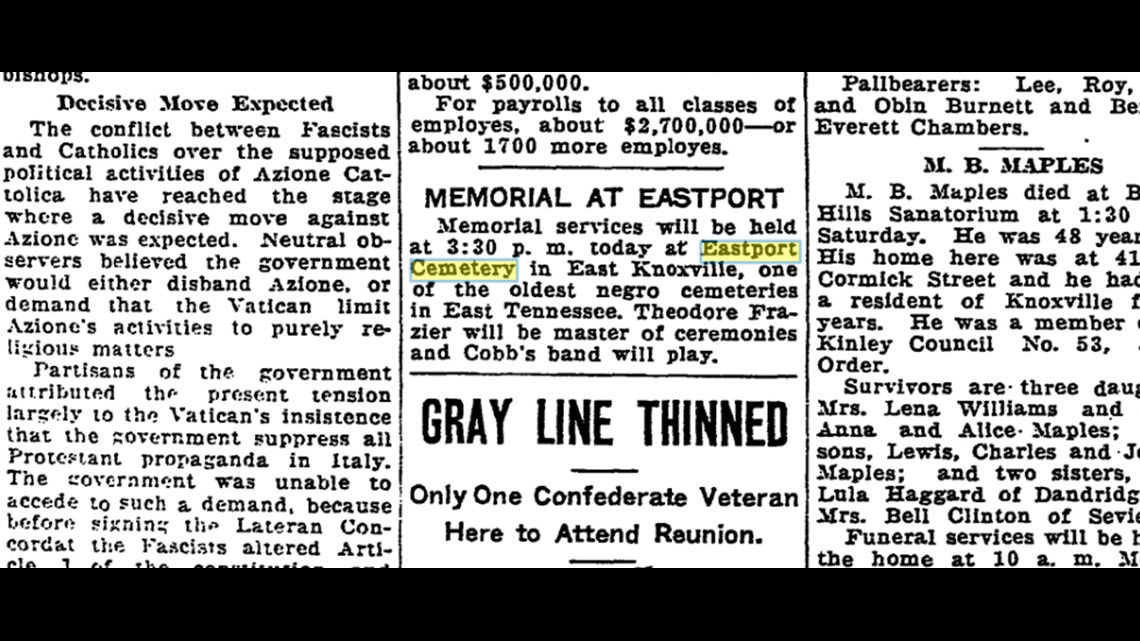

Eastport Cemetery, founded in 1836, has sat neglected more than 60 years. The last burial is believed to have taken place in the 1950s.

Although a handful of citizens would like to save it and renovate it, the chances of that appear slim.

It would take so much work to clear it -- trucks, chainsaws, bulldozers working day after day -- that the task appears too great to tackle.

And then there's this: Who would do it? Who would want to?

Knox County owns two contiguous cemetery parcels, acquired in 2007 in a tax sale. But it has no plans and no duty to restore it, county officials say. As for who owns the rest of the Eastport site, it appears no one has done a clear search.

"There are actually stones up there where you'll see a corner in a tree. Where the tree not only grew up next to it but began to wrap around it and encircle it," said Stephen Scruggs, who has led a successful effort to save another historic black cemetery, Odd Fellows, on Bethel Avenue.

"So you'll see the worst of the worst there."

East Tennessee historian Robert McGinnis calls it a "wasteland. The worst jungle you could possibly think of. I wouldn't want my family buried in something like that."

How it got that way is a reflection of changes in society and shifting values.

Sometimes we preserve the graves of our elders, trimming the grass, pulling the weeds, cleaning the stones. Other times we give in to the passage of time.

Hidden in Plain Sight: The historic Knoxville cemetery abandoned to the ages

The common, the remarkable

Eastport includes the graves of slaves who worked Col. John Williams' plantation nearby on Dandridge Avenue. Williams married Melinda White, the daughter of Knoxville's founder James White. Acclaimed playwright Tennessee Williams traced his ancestry to John Williams, a former U.S. senator.

Nine years after Eastport became a cemetery, Knoxville's oldest black church opened just yards away on Fuller.

A plaque erected in 2015 commemorates the original site of Warner Tabernacle African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, now known as Greater Warner Tabernacle and located on Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue. It was thought to be a stop on the Underground Railroad, the network that helped slaves escape the Deep South in the 19th century, said McGinnis, who has written books about East Tennessee cemeteries and is curator of James White's Fort on Hill Avenue downtown.

Both freedmen and slaves were buried in the 1800s in Eastport. Until the 1880s, when Odd Fellows opened, it was the main resting place for black people in Knoxville.

McGinnis, based on his research, estimates there are perhaps 6,000 buried there. Not all have gravestones. Many, in fact, went without. Some graves have caved in on themselves.

He isn't surprised the cemetery has slipped out of the black community's mind.

"It's quite prevalent in East Tennessee to see that kind of thing," McGinnis said. "Not just in the African-American community but in our own Caucasian community. Some people don't think about the dead the same way others do."

McGinnis's research offers clues about those buried in the sloped ground.

He knows, for example, of the Mason family, who operated a school for deaf black children after the Civil War on the old Williams home place. James Mason helped found Shiloh Presbyterian Church in East Knoxville, the first "Colored Presbyterian Church" in town, according to the church.

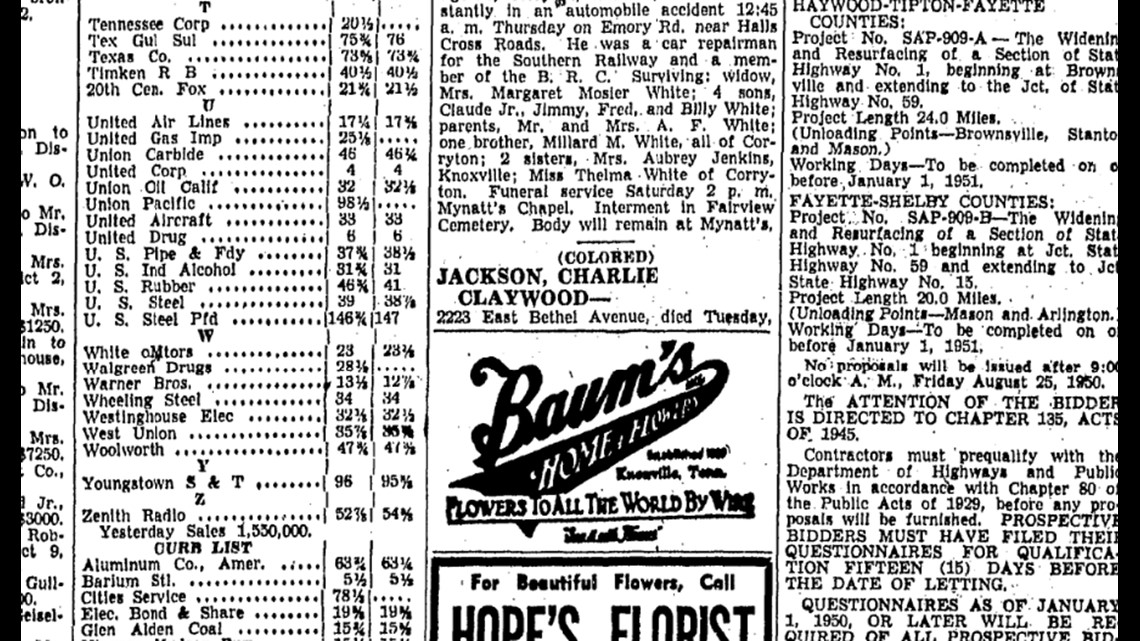

Old newspapers examined by McGinnis offer up other tales of both the average and extraordinary.

An April 1886 article in the Knoxville Chronicle relays the funeral of a man named Charley Mitchell.

"There was quite a lengthy cortege," the story states. "For some years past he had been employed in the railroad shops in this city and by his industry and sobriety was promoted to a lucrative and important position. His presence will be sadly missed."

In June 1886, "Uncle David" Scaggs died at age 60 at his home on Gay Street. He was born in 1825 in Cocke County, according to a story in the Knoxville Journal. He'd been a jockey and a barber, with a shop on North Gay Street near Vine Street. He, too, helped found Shiloh Presbyterian Church after the Civil War.

Fannie Clark died in 1894 at age 96. She was born into slavery in 1798 near Mussel Shoals, Ala. The slave owner, according to the story, sold her to another man and she ended up in East Tennessee.

In 1863, at the age of 65 she became a free woman thanks to Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, according to a death notice in the Knoxville Journal.

"She was a remarkable woman in every respect and retained full possession of her reasoning facilities to the day of her death. Aunt Fannie was greatly loved by many people and was one of those famous antebellum housekeepers and cooks and she prepared many a superb banquet for many a notable wedding..." the story states.

Somewhere in Eastport's decrepit, roughly 4 acres of dense overgrowth lie the remains today of Charley Mitchell, David Scaggs and Fannie Clark. Along with thousands of others.

What do we do?

Knox County isn't in the cemetery business. But it ended up acquiring two contiguous pieces of Eastport on the south side of Fuller in a public tax sale in 2007, according to Ben Sharbel, the county's supervisor of property development and asset management.

Before that the city of Knoxville briefly owned at least one of the parcels, according to documents. And before that, records show, Lula Pollard was an owner. Records aren't clear who owns the other surrounding pieces, and Sharbel doesn't know if anyone has ever tried to find out.

Documents identify Good Citizens Cemetery as the owner of one piece, but what that means is really anyone's guess.

While most of the cemetery is located south of Fuller and west of Addison Street, some graves sit in overgrowth on the north side of Fuller. McGinnis said people likely are buried under homes off Addison and perhaps in a residential cul de sac to the south.

Some of the dead also probably are buried under Addison, he said.

"The way that street cuts through it you almost think that if you took a ground-penetrating radar you'd find graves under there," he said.

Sharbel said employees only discovered after the tax sale that the county had acquired part of a cemetery.

The county handles hundreds of pieces of tax delinquent property. It typically is obliged to make the first bid when derelict properties go up for sale, but the hope is that someone else will make a bigger, better bid and put the property back on the rolls themselves.

In Eastport's case, that hasn't happened.

Polluters occasionally dump trash and construction materials on the fringes of the cemetery. The city and county both have come out and picked it up in the past. Today, the edges of Eastport appear mostly trash free.

In the past, volunteers have tried to clean up and clear out the sides. But the graveyard is so overgrown, the vegetation just grows right back, McGinnis said.

Ideally someone would come forward and take responsibility for the county's two parcels as well as the rest of the graveyard, Sharbel said. The county would work to transfer the land to a legitimate buyer, he said.

Until then, the county's only concern and duty is to ensure there's no threat to the safety of the public.

"We tried to figure out -- what do we do? So we've kind of been there ever since," Sharbel said.

'My little niche'

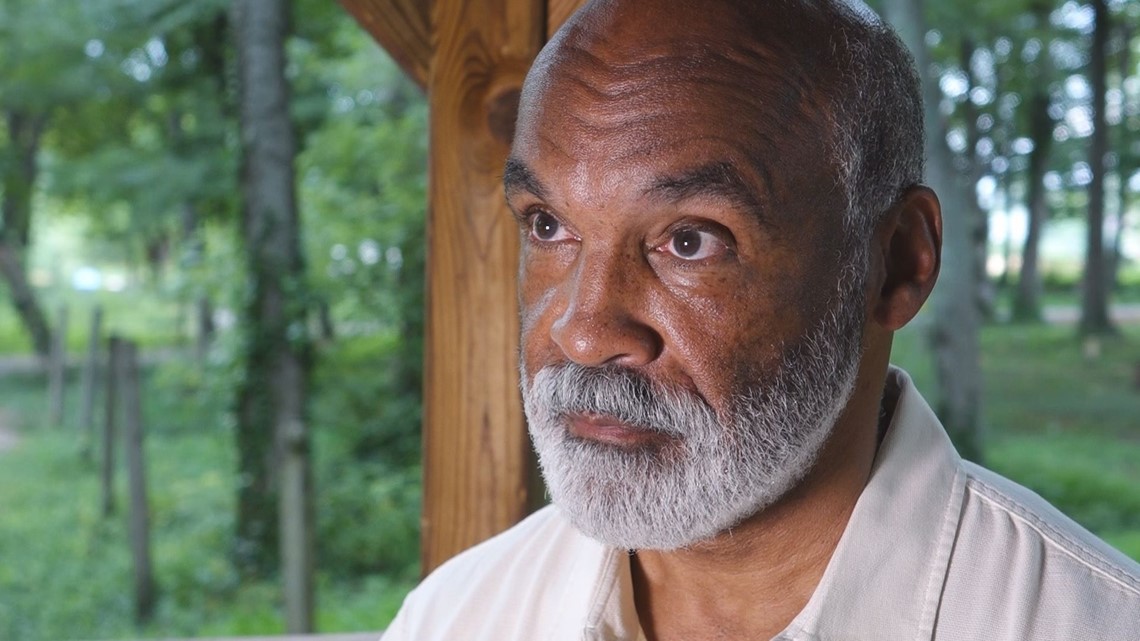

George Kemp isn't giving up, at least on his little part of the cemetery. George Kemp won't give up.

The lifelong Knoxvillian and retired Knox County Schools educator faithfully tends to a family plot on the northeast side of Eastport Cemetery by Addison and Fuller. Buried here are his father, a cousin, an uncle.

Kemp's family purchased the plot decades ago. His grandmother told him people bought land in the cemetery with the expectation that families would assume responsibility for the upkeep.

That method worked, more or less, until families began to move away and die off.

"The people who are buried here aren't getting their just due," said Kemp, who grew up near Fuller. "I'm sure many of the families are no longer around."

The forest that chokes Eastport looms over the Kemp family ground. Kemp goes out there faithfully, keeping the grass trimmed and pulling out the weeds. He took on the job a couple years ago when an aunt, in her 80s, had to stop.

In March 2013, before spring growth began, Kemp and Scruggs went into Eastport looking for the burial site of a church bishop. They couldn't find him, but Kemp was struck by what he saw: "You have very intricate and elaborate headstone work and then you have very simple and plain. It runs the gamut of who's in there."

Swales in the ground indicate where graves have collapsed. In many spots only the corner of a stone sticks out above ground. The rest -- claimed by the elements.

They haven't been back since. They certainly wouldn't go in the summer, when you can't see what lurks under your feet.

Odd Fellows, which came along after Eastport, was fortunate in that people were ready to work to bring it back. Its highly visible location between Bethel and Kenner avenues near the old Walter P. Taylor Homes development helped ensure generations today still know about it.

Eastport, tucked off a side street in a small, quiet neighborhood, hasn't been so fortunate.

Scruggs, who has worked so hard to preserve Odd Fellows, doesn't think the community desire exists to save Eastport.

There are some problems that can't be solved, he said. In the old cemetery's case, it might be best to bring a bulldozer in, smooth the site over and declare it a single memorial to all who reside there.

"I think the best you can do is turn it into a collective memorial as opposed to individual memorials," he said. "Because individuals require individual care. A collective memorial you might be able to get help from organizations."

McGinnis, along with Kemp and Scruggs, likely is among the few who has trekked so deep into the abandoned graveyard. Fixing it up would require a lot of money.

"A lot of times I say it's just better to leave them alone," he said. "I know that it looks bad. But considering what our ancestors thought about the dead and how they revered the dead, we're never going to get back to that point."

Kemp wishes someone would come forward, but he knows it involves "a gargantuan task."

He doesn't plan to be buried there himself. He has his own space elsewhere. But he will look to his children some day to carry on his work at the Easport site.

"I just think it's like a passing of the baton," he said. "I'm concerned about everyone else around, but I know the reality of what I can do. This is my little niche right here, and I'm going to try to keep it as clean and presentable as possible."