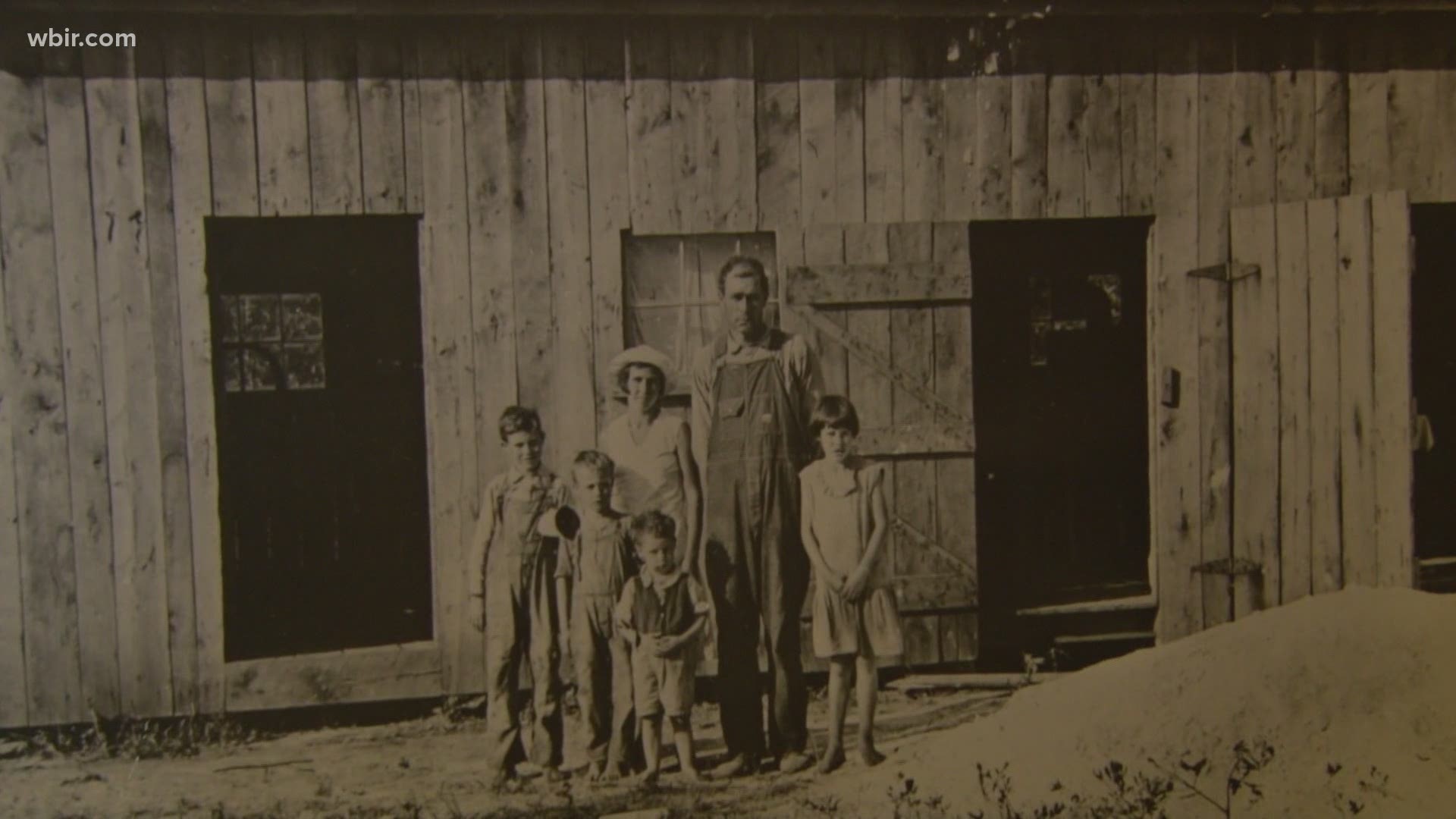

CUMBERLAND COUNTY, Tenn. — During the Great Depression, the Cumberland Plateau was one of the places the federal government looked to jumpstart the nation's economy. With that designation came a new rural resettlement program created with the New Deal that offered optimism and opportunity for many Tennesseans.

Out of thousands of applicants, more than 200 families were given a chance to work in exchange for a house and farmland. The community of houses and other buildings, like the 8-foot water tower, are still standing today and serve as museums to preserve the area’s history.

Established in 1934, the Cumberland Homesteads was the only rural resettlement project in Tennessee and the largest of the hundreds of communities built by the Division of Subsistence Homesteads.

“This gave them a chance and gave them hope when they had lost all hope at that time,” Kelly Cox said.

She serves as the museum director and manager for the Cumberland Homestead Tower Association, the non-profit organization which maintains the history of the community.

“The main reason that it was so successful is because these families were so desperate and they were willing to work, they were willing to do anything that they had to do in order to have a home again,” she said, adding that most of the people who applied were unemployed miners and textile mill workers.

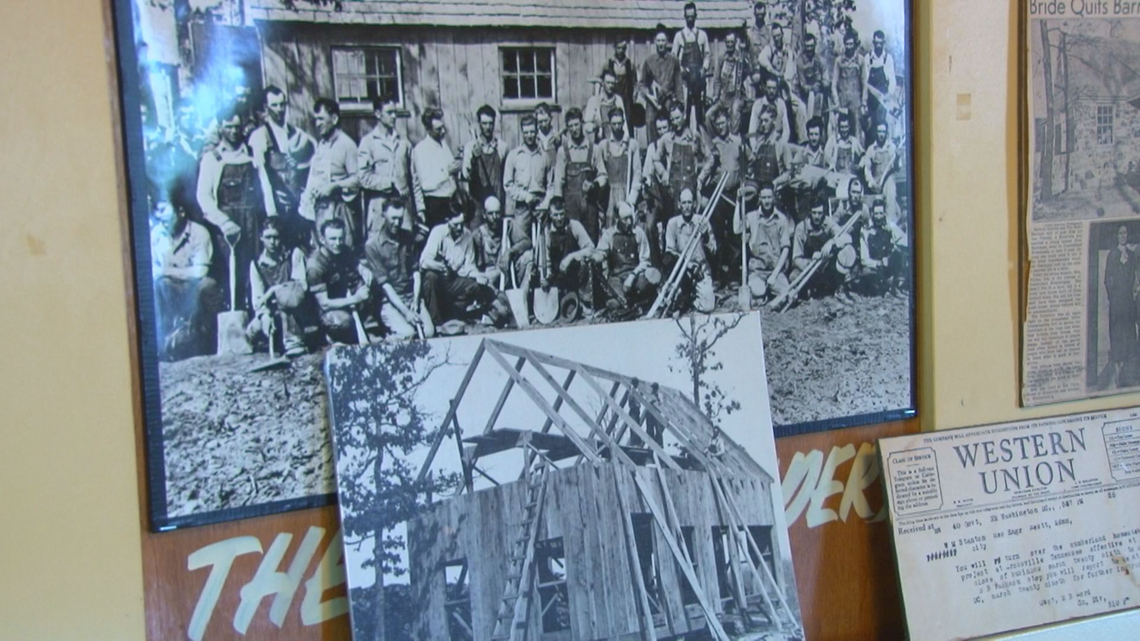

The new homesteaders became part of the Civilian Conservation Corps under the Works Projects Administration.

Home sweet home

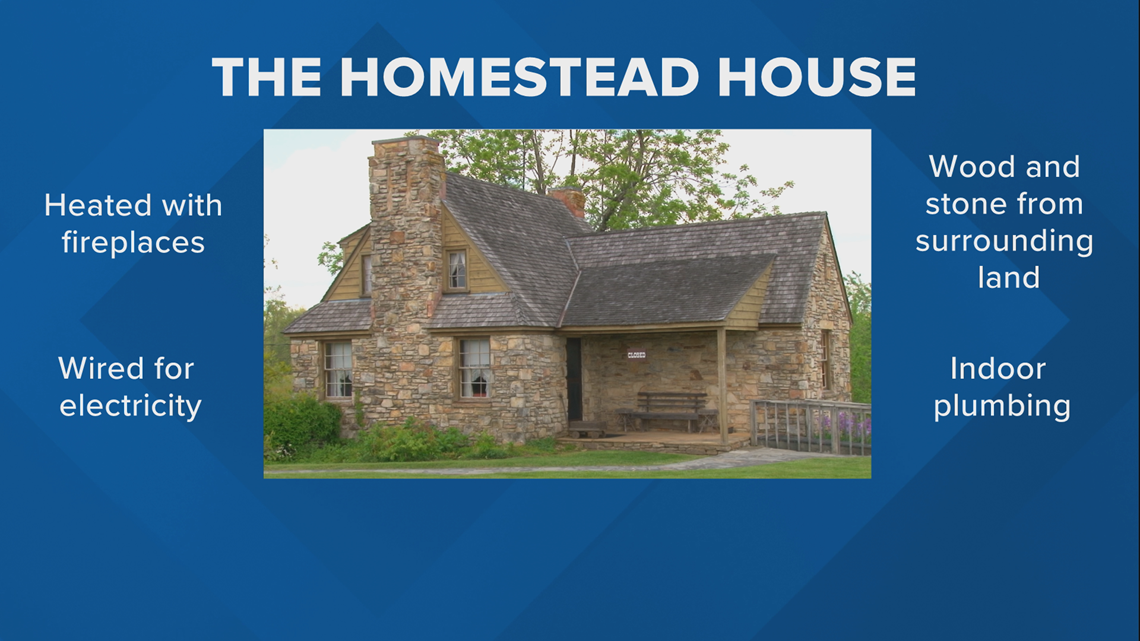

The houses were designed by architect William Macy Stanton. All of the building materials, like wood and stone, were taken from the land around the homesteads.

“I think one reason we were chosen here on the Cumberland Plateau was for that reason -- for this Crab Orchard sandstone and it's very abundant in the area. Building these homes, that's the first time it was actually really publicized, but I think that's one reason why we have so many of the homes still standing is because this stone is sturdy, and the homes were well built,” she said.

Cox said when the project first started, the area was not cleared yet. It was considered a “stranded community.”

“All the timber was here, and they had their own sawmill,” Cox said. “The homes have hardwood floors, ceilings, pine walls. The Crab Orchard stone, it's used throughout the world now.”

The homesteads were heated with fireplaces and were some of the first homes in Cumberland County to have indoor plumbing. They were also wired in anticipation of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s creation. The homes eventually had electricity by 1987.

But that didn’t come without some pushback. Cox said because these homes were so nice, the Cumberland Homesteads were controversial.

“A lot of people felt like they were nicer than what some of the prestigious government officials had lived in,” she said. “It was a little controversial in that area.”

In addition to trade skills, the project worked with the University of Tennessee Agricultural Department to teach homesteaders about maintaining their farms and growing food.

“There were families that were chosen to monitor their nutrition stats so they would kind of weigh the children when they started and keep a log of the things they ate. And then just kind of experiment with the ways they were eating and how much better it got the longer they were in the project,” Cox said.

The state park

Other woodlands that were not suitable for farming were set aside for community use. What began as the Cumberland Homesteads Park eventually became the Cumberland Mountain State Park.

Constructed in conjunction with the homesteads, the Civilian Conservation Corps built cabins, a man-made lake, a beach, a boathouse and hiking trails.

Again, Crab Orchard sandstone was used to construct many of the buildings. In fact, the stone bridge is the park’s most well-known landmark and the largest masonry structure ever built by the CCC, according to Tennessee State Parks.

“They had all of these young families with lots of energy and they needed somewhere for them to go and have recreation and it was a very stressful time,” Cox said. “When they had an opportunity to get to go and swim, just relax and be with their family and friends, that was extremely important for the community.”

History lives on

Today, much of the homesteads are still standing. One of the original houses and the water tower operate as museums, preserving the history and offering an opportunity for visitors to explore life on the cusp of the depression.

The museum features artifacts of homestead life including handmade furniture.

Cox said the Cumberland Homestead Tower Association relies on donations and a big fundraising event in September to keep everything running.

Cox said another big part of preserving the history of the area is record-keeping. She said the CHTA recently received a grant to expand and organize their archives to track the homestead families as far back as they can.

“We have an abundance of records here,” he said. “We encourage people to come and research their families."

You can learn more about how to donate or become a member here.