The Music of the Mountains: African American artists in Appalachia

Black music has been present in East Tennessee since the 1790s. Since then, many artists have contributed to the tapestry of sounds Appalachia is known for.

From Elvis to Usher, Timberlake to Tina Turner to Three Six Mafia, the state of Tennessee has produced innumerable musically gifted artists.

In the Great Smoky Mountains, Appalachian music birthed the sounds we know as country, bluegrass and rock and roll. For every superstar like Dolly Parton or Kenny Chesney, there’s a Clarence Beeks or a Leola Manning, artists that helped pave the way for all future Tennessee musicians but have faded into obscurity since their heyday.

In celebration of Black History Month, we shed a light on these forgotten musical figures.

Origins

Some of the first documented cases of Black music in the area came by way of banjos on riverboats making their way into Knoxville.

The sounds of the banjo led to the introduction of what we know today as the blues ballad.

“They were story songs introduced by African American musicians, often telling stories based on prominent African American figures in the community. Sometimes mythologized, and sometimes quite accurate and documentary of the real deeds of real people," Professor of Appalachian studies at East Tennessee State University Dr. Ted Olson said.

The most famous of these mountain melodies was the song “John Henry.”

“'John Henry' is probably the most popular Appalachian song of the last 150 years. I think what really is important is that the ballad was so powerful, it transfixed across the entire population and people in all walks of life sang 'John Henry' and continue to sing 'John Henry' today," Olson said.

By the turn of the 19th century, the banjo had been adopted by whites and used in minstrel shows, which were quickly becoming the premiere form of entertainment across the country. The performers in these shows often learned to play the banjo from slaves.

Black Appalachian music carried on, but given the lack of documentation at the time, a lot of the early African American musicians have, unfortunately, been lost to time.

Encompassing influences from cultures the world over, such as African, Native, Scot and Irish—the music of the mountains is something truly unique.

“All this music fused together to create the blend that is now today Appalachian music. Black music is an essential part of that blend. It’s been overlooked, but it deserves recognition, and exploration, and appreciation,” Olson said.

Lesley Riddle

Lesley Riddle was born in Burnsville, North Carolina in 1905. Growing up, he often traveled to Kingsport to stay with family, eventually making the East Tennessee town his permanent home.

During his youth, an accident with a firearm cost Riddle some of the fingers on his hand. He was able to find work in a cement factory until 1927 when he tripped on an auger. The injury resulted in the amputation of his right leg up to the knee.

“His uncle gave him a guitar to pass the time as he was trying to recover. He became completely absorbed in music. He played with the rest of his fingers, and it created a sound and a rhythm that was very distinctive,” President of the Traditional Voices Group Ellen Denker said.

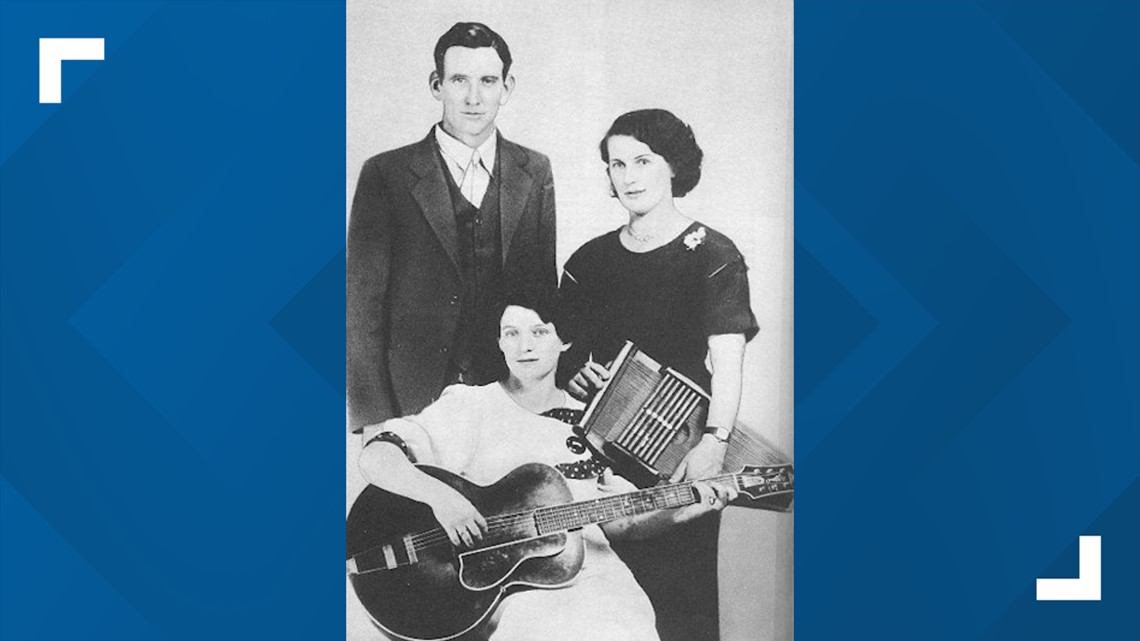

Riddle would busk in the streets of Kingsport to try and eke out a living. In 1928, he was approached by A.P. Carter, one of the premier country music artists in the area.

Carter offered Riddle the opportunity to travel the mountains with him and memorize the melodies he heard while Carter would write down the lyrics. Riddle agreed and the duo would work together well into the 1930s.

Riddle acted as composer on a multitude of songs for Carter and the other members of the Carter family, Maybelle and Sara, all while going uncredited for his work.

“Lesley Riddle didn’t get credit for having arranged many songs for the Carter family. It wasn’t that the Carter family were trying to deny him his rights, they always spoke very highly of Lesley Riddle and liked him immensely. It was simply the way the industry operated in those years. It was highly segregated and discriminatory," Olson said.

Riddle married in 1937 and moved to New York in 1942. He would not play secular music again until the 1960s.

Folk musician Mike Seeger had just finished a collaboration with Maybelle Carter who confessed that she learned to play the guitar by watching Riddle. Seeger sought out the former musician and convinced him to return to his roots. The two toured and recorded music for the next 13 years.

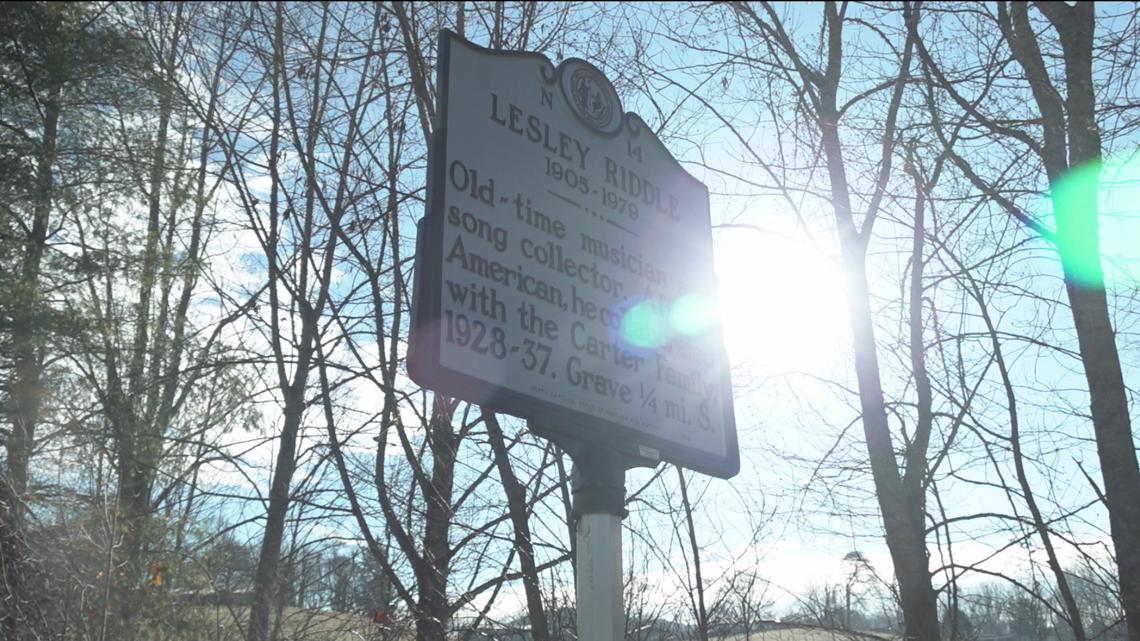

Lesley Riddle passed away in 1977 after a bout with an illness, but today, the town of Burnsville continues to honor the legacy he left behind.

There is a historical marker bearing his name as you enter the town, and in 2008, the Traditional Voices Group started the annual event known as RiddleFest. The festival brings in artists from around the region to play and celebrate the music left behind by Lesley Riddle.

“To have that kind of recognition, I wish he could have seen it in his lifetime. I think he would’ve been embarrassed about it. I don’t think he would be wanting to receive that limelight. It’s just wonderful that Burnsville has stepped up and was at the forefront of reviving his music and acknowledging his contributions to country music and I think that it has spread tremendously," Riddle's great niece Cathy Henson said.

Wallace Coleman

Blues harmonica player and Morristown native Wallace Coleman first picked up the oral instrument from a friend in Oak Ridge, and the first song he ever played was "John Henry."

Coleman’s mother was an avid ukulele player with sounds steeped in country and gospel, but it was a local radio station that piqued Wallace’s interest with the unique sound they called the blues.

“I remember when I first started listening to WLAC, and they had all of these records by Little Walter and Muddy Waters and Howling Wolf, and I could go to school, and sometimes I could hear that music in my head. I could actually hear the music while the teacher was talking, and I knew then, something about the music that just grabbed me. It never left me," Coleman said.

Coleman left Tennessee in the 1950s and moved to Cleveland. He found employment with his stepfather at a bakery and brought along his harmonica to practice on his work breaks.

One of his co-workers introduced him to local artist Guitar Slim. Slim asked Coleman to play and perform with him but, unsure of his ability, the self-taught harmonica player was hesitant to begin playing with Slim.

Eventually, Coleman gave in and began a partnership playing in clubs around Cleveland. The duo’s performances were halted after only a year, as a new form of music took over and the blues were pushed out.

“When the '60s came in, and Motown wiped out the blues, the Black people stopped playing blues. The only guys that are really playing blues today, especially traditional blues are the older Black guys like myself," Coleman said.

His time playing in clubs wasn’t for naught, as Coleman’s harmonica skills caught the attention of famed blues guitarist, Robert Lockwood Jr., who offered Coleman an opportunity to join his band. However, Coleman wished to retire from the bakery before he committed to touring.

In the 1980s, at the age of 51, Coleman gave Lockwood a call. Over the next decade, Coleman toured as part of Lockwood’s All-Star band, and performed on his Grammy-nominated CD, “I Gotta Find Me a Woman.”

In 1996, Coleman branched out yet again to form the Wallace Coleman Band and released his first album the following year. At the turn of the millennium, Coleman started his own record label, Pinto Blue Music, and after traveling the world with Lockwood, Coleman finally returned home to perform in Morristown.

“If you listen to a real true blues person, you can almost tell that he's had a lot of pain in his life. I've had quite a bit, but I've never felt that I was down on myself. It gives me great joy to really express myself. I don't know of any better way of expressing who I am than to play music for people," Coleman said.

Wallace Coleman still tours across the world and is considered the standard-bearer for the blues harmonica.

Howard Armstrong

William Howard Taft Armstrong, known in the music world as Louie Bluie, was born in 1909 and grew up in Lafollette. His father was an ironworker and his mother stayed at home to tend to their large family.

Armstrong grew up in the poverty-stricken coal camps of Campbell County where he was able to pick up multiple languages from the melting pot of different cultures that lived there.

During his teenage years, Armstrong taught himself how to play the fiddle and joined his brothers, Roland and Carl Martin, in a band. The trio toured the nation singing spirituals and songs of all sorts, eventually setting up shop in Knoxville.

In the late 1920s record companies began holding extended recording sessions with artists in East Tennessee cities like Johnson City and Bristol. In 1929, prominent record label Vocalion held sessions in Knoxville at the St. James Hotel.

When the second St. James recordings took place in 1930, the group, now known as the Tennessee Chocolate Drops, recorded songs for Vocalion Records such as “Knox County Stomp” and “Vine Street Rag."

Soon joined by guitarist Ted Bogan, the quartet toured with a medicine show as a backup for the lead blues act. By 1934, Armstrong had been given the nickname “Louie Bluie” and performed at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago. Although he added songs in different languages to his repertoire, the public wasn’t always accepting of the music Armstrong played.

“I remember one time we were getting down on some low-down dirty blues. A man came over to say, ‘What kind of music are y’all playing?’ One of them jumped up like a fool and said, ‘The blues!’, he said, ‘You better turn them red because we don’t want to hear that funny kind of stuff that y’all are playing.’ So, we had to let it go," Armstrong said.

Armstrong took time away from music to serve in World War II. He then moved to Detroit and worked in the auto industry until the early '70s. He got the band back together; by then, it seemed that people had changed their tune about the blues.

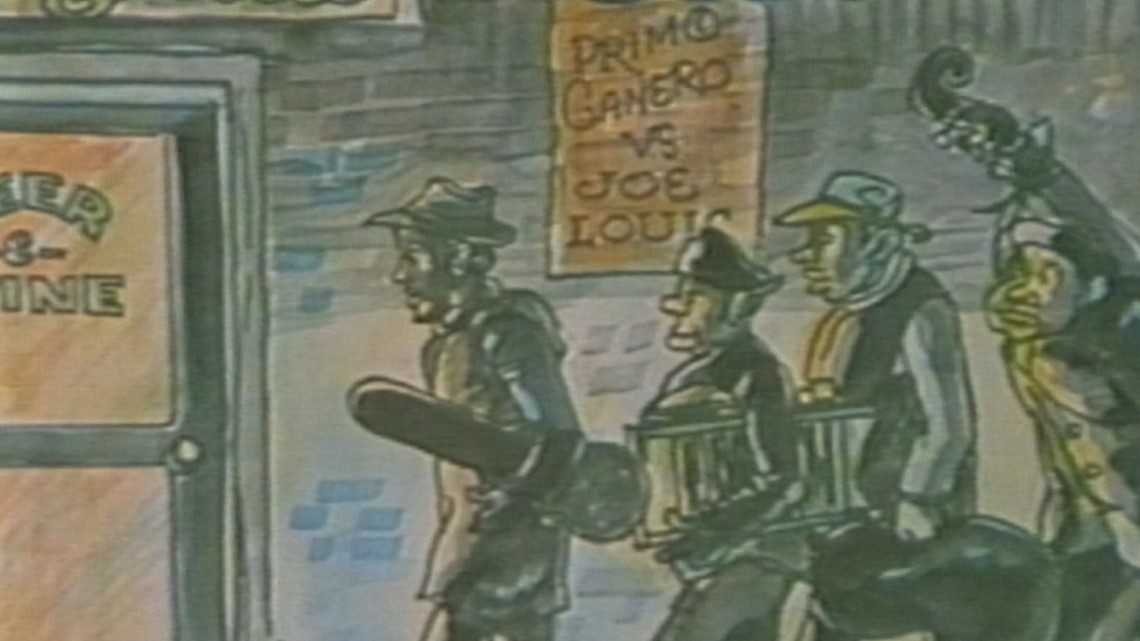

The band toured together until 1979 when Ted Bogan passed away. Aside from his musical prowess, Armstrong was a talented painter. He created many of his band’s album covers and even helped build one of the sets for the movie, “The Color Purple.”

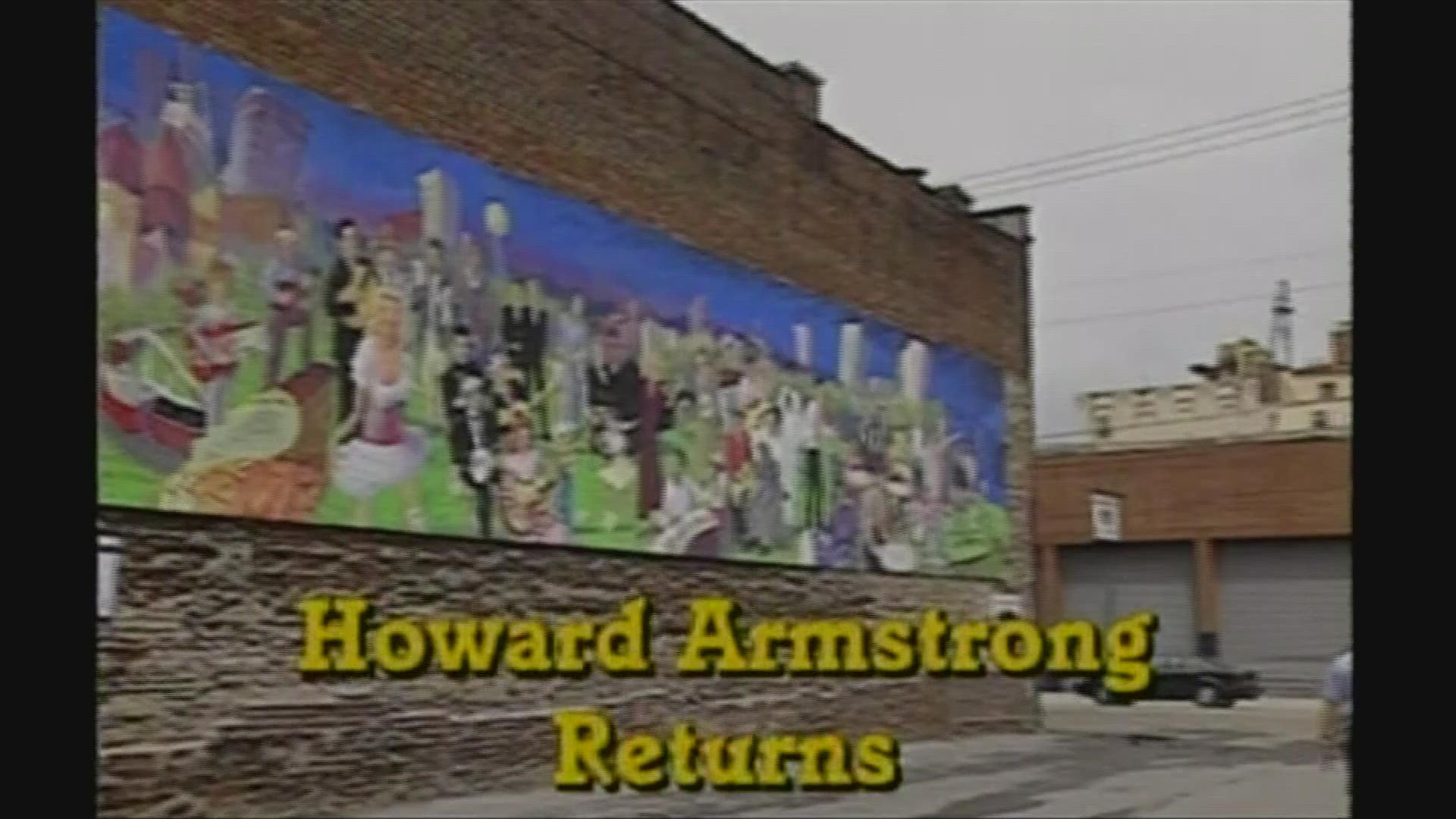

In 2000, a mural was unveiled highlighting the history of East Tennessee music. Among those depicted was Howard “Louie Bluie” Armstrong.

“They say music is a universal language. A guy would rather hear you playing a beautiful song than running some jive on him," Armstrong said.

Armstrong passed away at the age of 94 in 2003, but his legacy carried on.

Since 2007, the Louie Bluie Music Festival has been held in Lafollette to honor the late fiddler.

In 2022, the city of Lafollette unveiled a Tennessee Music Pathways historical marker to forever commemorate Armstrong’s contributions to the city and to music.

“It means an average layman can live his dreams and accomplish his dreams by trying and having perseverance and faith that if you want to do something you can get it done," Armstrong's grandson Ralphe Armstrong said.

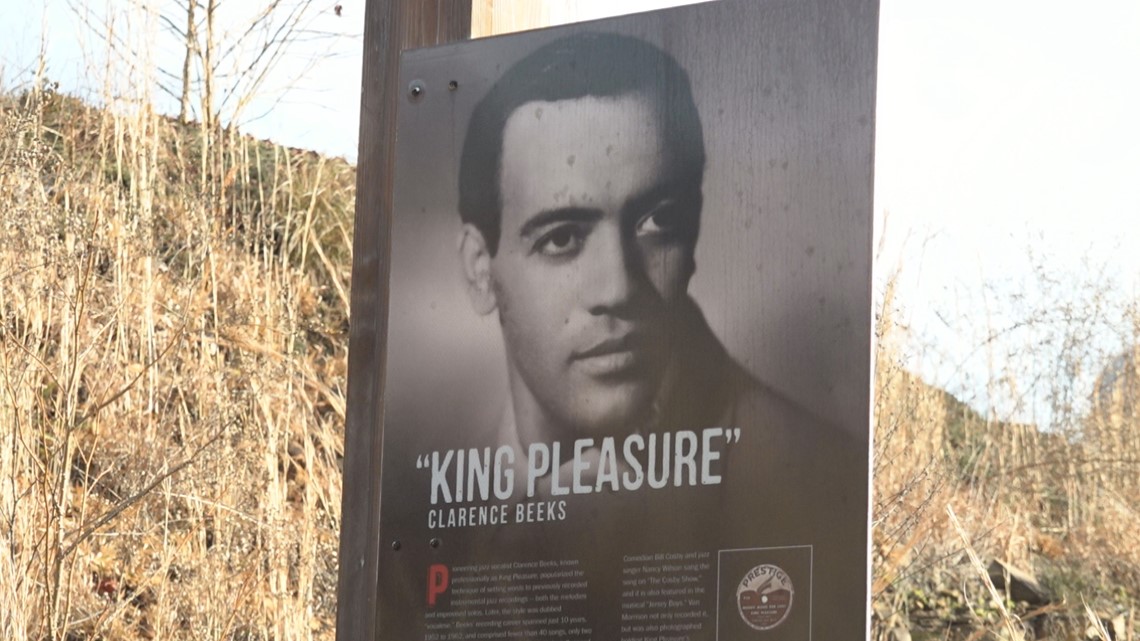

Clarence Beeks

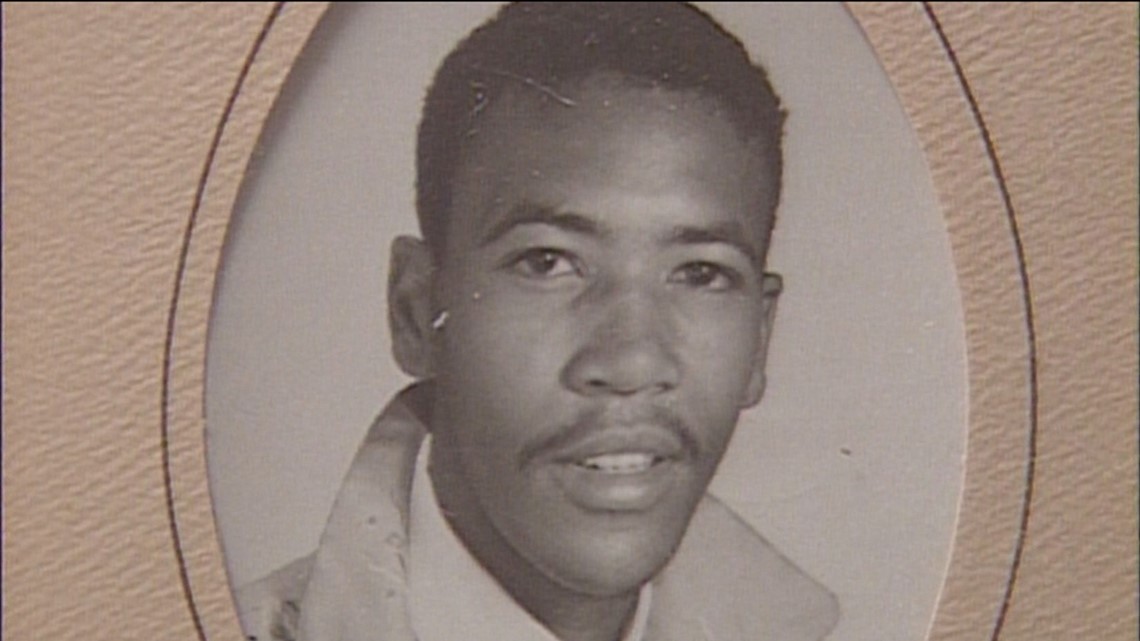

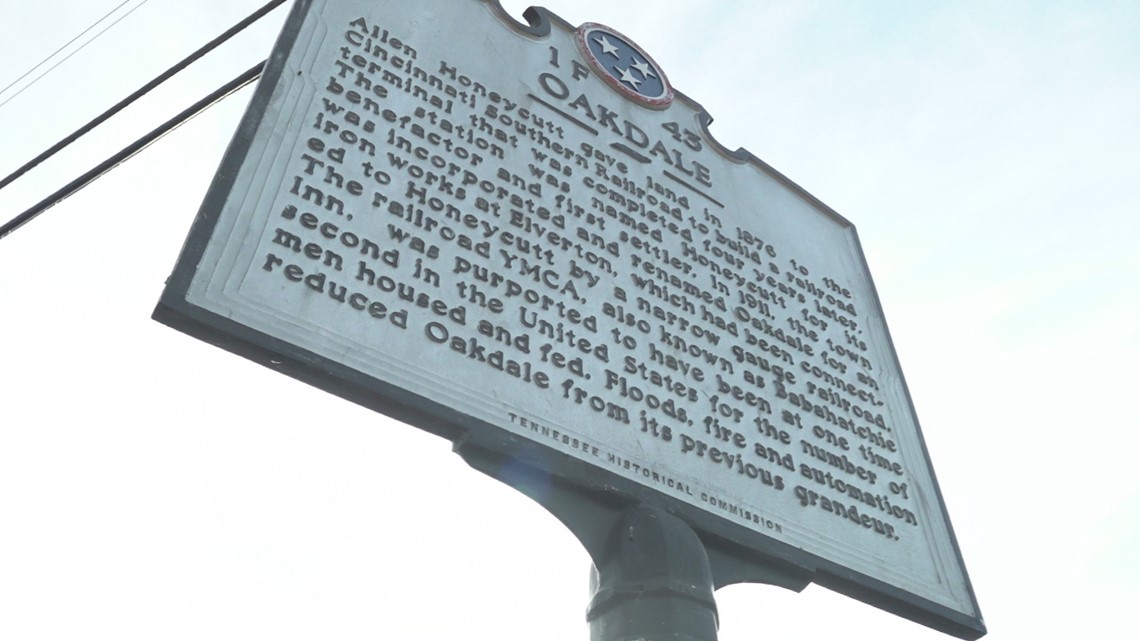

Clarence Beeks was born in the small railroad town of Oakdale on March 24, 1922.

“There weren’t that many Black people in Oakdale. It was the only place in Morgan County where Blacks could live and work. So, they worked on the railroad,” Oakdale historian Vera Scarborough said.

Both his father and grandfather worked along the tracks, but at an early age, Clarence told himself he wanted to be something more.

By the age of six, a young Beeks had already given himself the moniker of King Pleasure. He relocated to Ohio with his mother and traded the train tracks of Oakdale for tracks of a different kind.

“Clarence went on to Cincinnati. His mother took him on the train. So, we don’t hear from Clarence until he becomes this well-known singer and musician," Scarborough said.

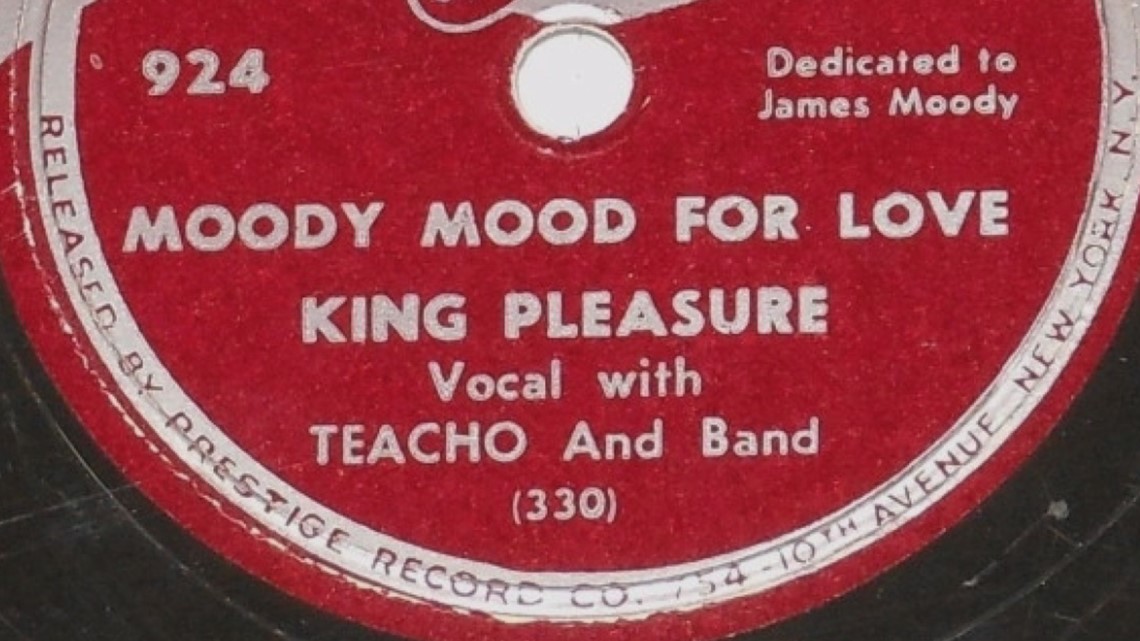

In 1951, King Pleasure won a contest at the world-famous Apollo Theater in New York and was signed to Prestige Records. In his first session with the jazz label, Beeks laid down the track “Moody Mood for Love” in which he delivered improvised vocals over the previously recorded jazz instrumental of “I’m in the Mood for Love” by saxophonist James Moody. This style of freestyle music would go on to be known as “Vocalese.”

“Vocalese is very much like rapping jazz. He sings then he repeats what he sings, and he repeats it in several different ways. He’s a bit telling a story and he’s singing. His music is kind of like cooing and gentle and like a breeze blowing,” Scarborough said.

“Moody Mood for Love” went on to become the number two R&B song in the country and popularized the style of “Vocalese.” He followed up his first hit song with another entitled “Red Top” in 1953. His final session for prestige came in 1954 and was produced by Quincy Jones. Beeks continued performing and recording until he released his last album in 1962.

After his final album was released, Beeks stepped away from the music industry.

In a 1958 article from the Pittsburgh Courier, Clarence voiced his disdain for the recording industry, which may have led to his exit from music. After his career, Clarence settled in Los Angeles before he passed away in 1981 at the age of 59.

Since its release, “Moody Mood for Love” has been covered by Queen Latifah, Aretha Franklin, Amy Winehouse and many others. King Pleasure has become the favorite son of Oakdale.

“There are so many people that are a part of America’s history. He joins many people who are far more well-known than he, and I hope what people take away from his story is that this small, little town in Oakdale, where this little boy grew up, had this God-given talent, and went on to use it and give pleasure to those who loved music,” Scarborough said.

Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith was born in Chattanooga in the early 1890s, the exact date is unknown.

She grew up in the poverty-stricken area known as Blue Goose Hollow. Orphaned at a young age, Bessie was raised by her sister. Wanting to provide for her family, Bessie and her older brother, Clarence, would perform in the streets for pennies.

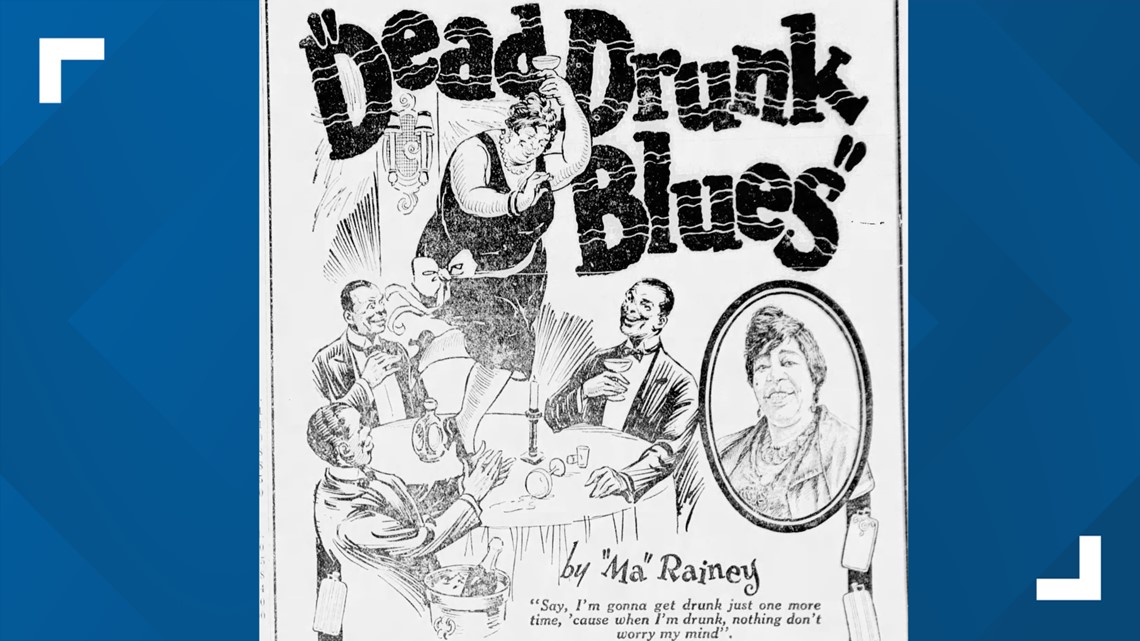

In 1904, Clarence’s talent eventually landed him a spot traveling with a small, music troupe. When he returned years later, Clarence was on tour with one of the prominent African American acts of the time.

“Ma Rainey was the headliner on this particular tour. Ma Rainey saw Bessie perform and thought Bessie was someone that might fit in. Her brother encouraged Ma Rainey to give her a chance,” Director of Community Relations for the Bessie Smith Cultural Center Elijah Cameron said.

Smith joined the tour and started out as a dancer, but soon joined Rainey on stage as a singer. Before long, Bessie was performing in chorus lines in Atlanta and headlining shows on the vaudeville circuit.

“After a while, everyone started to take notice of her. She was in New York at the time, and Columbia Records picked her up,” Cameron said.

Smith signed to Columbia in 1923 and recorded the first race record released on the label, “Cemetery Blues." She followed up with the song “Downhearted Blues” which went on to sell 780,000 copies in its first six months. With the success of her new record, Bessie began touring the country with her unique blues sound.

Before long, Bessie was the highest-paid female entertainer in the country, making in excess of over $2,000 per week.

Bessie’s success had her dubbed by the press “The Empress of the Blues." She sang about her life, her struggle and her sexuality. However, the topics of her songs, as well as her lifestyle, turned away some would-be listeners.

“Bessie was a brawler. Bessie liked to drink, and Bessie was somebody that you didn’t want to pick on. She could hold her own. She was someone who really enjoyed the spirit of the night. She loved her men, but on the same token, she loved her women. Bessie was someone, when you looked at her, you would say that ‘she’s not conducive to the times,' but she was conducive to the times. She continued to be a full force when it came to the blues,” Cameron said.

Bessie would go on to record 160 songs for Columbia, but by the end of the 1920s, the Great Depression put an end to vaudeville acts. She kept touring and had brief stints on Broadway and film and sold over six million records during her career. On September 26, 1937, Smith was traveling in Mississippi on her way to a performance when she was involved in a wreck with an oncoming truck. The accident nearly severed her arm, and she passed away in the hospital shortly thereafter.

Bessie Smith was buried in Philadelphia. Thousands of fans attended the funeral, but the singer’s grave was left unmarked.

A proper headstone was purchased years later by singer Janis Joplin.

Today, Bessie Smith’s legacy is alive with an African American Cultural Center carrying her namesake in downtown Chattanooga.

Leola Manning

Born in Chattanooga in 1905, Leola Manning and her family made East Tennessee their home by the mid-1910s.

Manning came from both a musical and religious home. She decided to follow in her mother’s evangelical footsteps and earned her vocal stripes singing in church.

When the St. James recording occurred in Knoxville in 1920 and 1930, Manning decided to lend her vocal talents.

Most of what Vocalion records found in Knoxville was country music, with a sprinkling of jazz and novelty music thrown in. Manning attended these sessions and gave the record label a more unique sound.

“She sounds like an urban blues singer, but her heart and her repertoire is much more gospel-based. She viewed herself as a church singer, not a blues singer. She never wanted to be called a blues singer. It had to do with her faith and her feelings that music needed to be upright and serve the religious community,” professor of Appalachian studies at East Tennessee State University Dr. Ted Olson said.

Manning recorded six songs in total during both the 1929 and 1930 sessions. The session included a mix of popular music and gospel songs, but also some original works.

"She recorded two songs that she wrote herself. The amazing thing is, she wrote them right before she recorded them. We know this because they describe crimes that happened right before the sessions took place. One is called 'The Arcade Building Moan,' Knoxville historian Jack Neely said.

In March of 1930, a deafening explosion rattled Gay Street and the Arcade Building was quickly engulfed in flames. Four people died in what was the worst fire Knoxville had seen in 20 years.

Manning’s second original song was titled “Satan is Busy in Knoxville.”

The song chronicled two recent murders in the city. One was the killing of Lefford Franklin, a Swan’s Bakery delivery driver who was robbed and murdered while making his final stop of the day.

The other murder occurred near Mountain View School where Leola Manning was employed as a cafeteria worker. The victim, Amanda Toole, was found with her head nearly severed by a rusty razor.

“It’s how she felt about her life. She felt like a lot of negative things were happening around her,” Olson said.

Vocalion never paid Manning for her contribution to the sessions, but her songs did enjoy a modicum of success in Texas and Oklahoma.

The six songs she recorded at the St. James Sessions were the only songs Manning ever recorded. Following her musical endeavor, she devoted her life to her faith and married her guitarist, Eugene Ballinger.

“She lived quietly in Knoxville and lived into her 90s. Her kids never heard that she had made recordings. Her family never heard that. It may have been something she may have forgotten about it,” Neely said.

Leola Manning’s work was dormant for almost six decades until the St. James recordings were uncovered and released as a set.

Today, blues scholars study the songs left behind by Leola Manning, and the St. James Sessions, now known as the Knoxville Sessions, have been released in their entirety.