SEVIER COUNTY, Tenn. — Music is a language that knows no barriers. It carries with it memories, culture and history. Southern Appalachian music has been telling the story of the people in East Tennessee and the Great Smoky Mountains for centuries.

African American musicians played a critical part in the sounds that we hear in many genres today and the sounds that we will hear in the future.

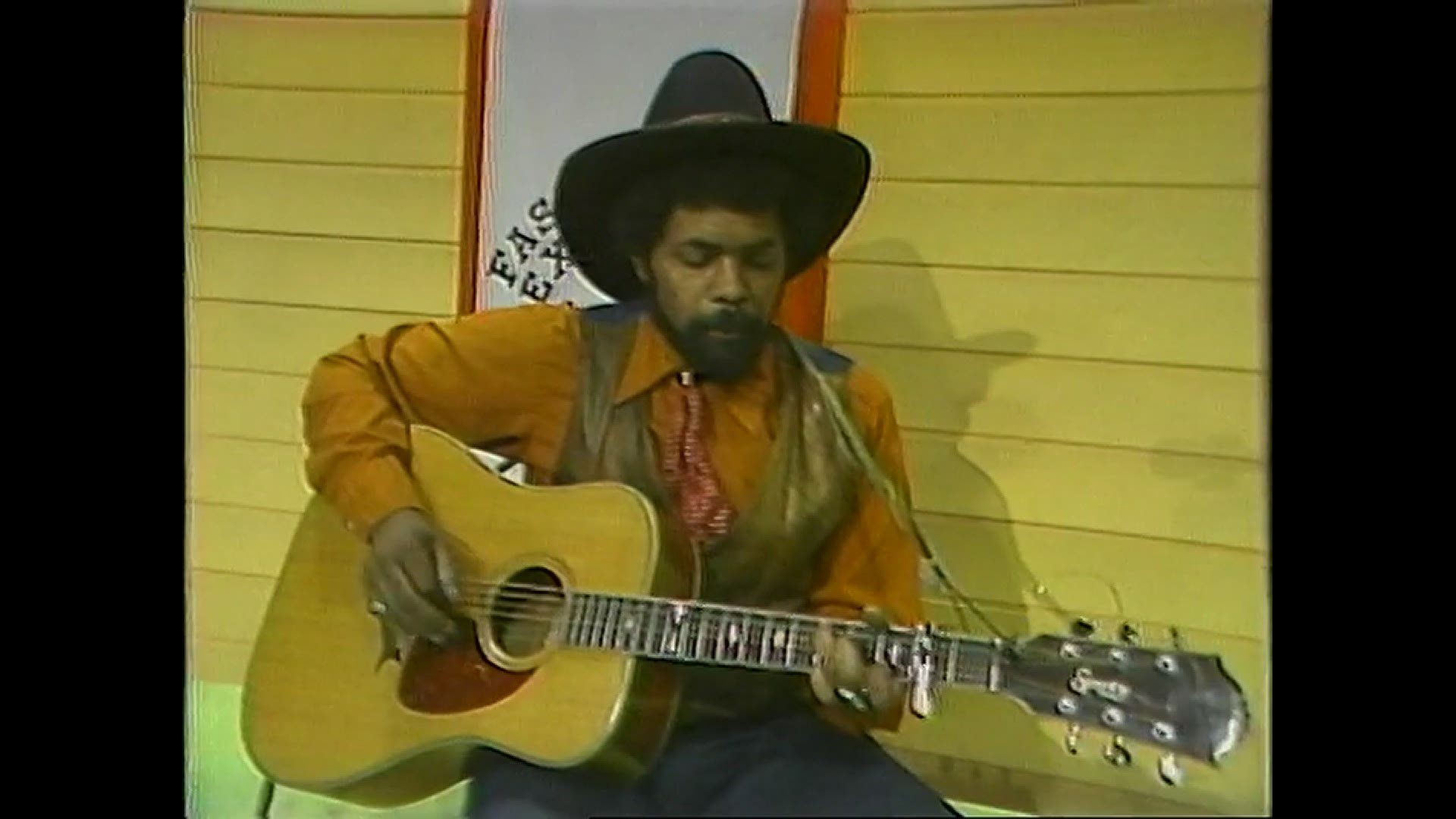

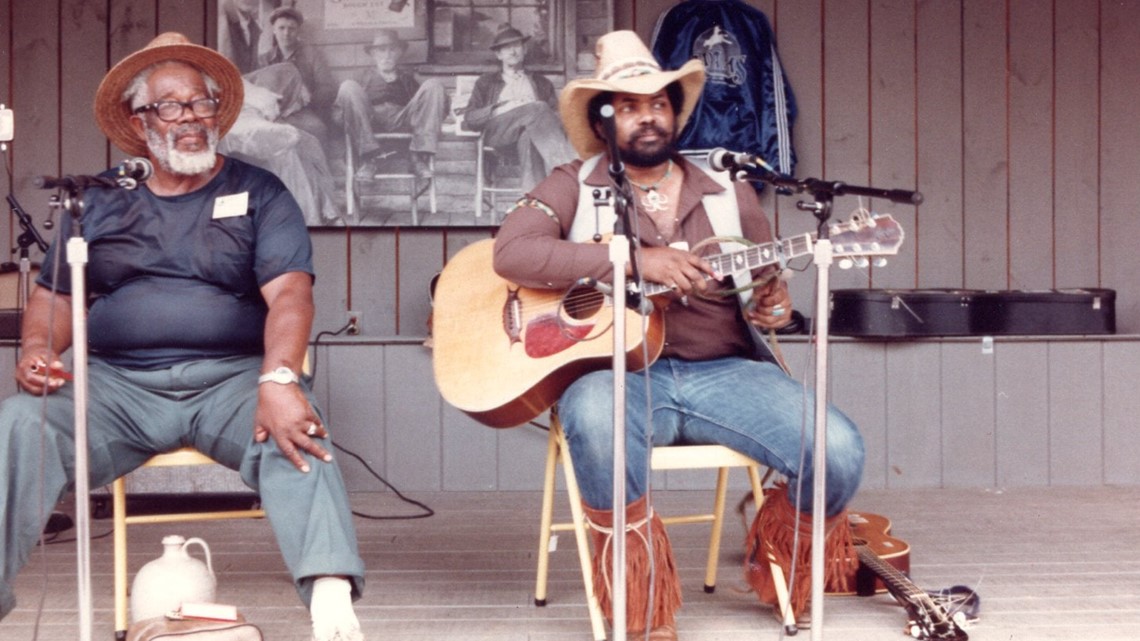

James “Sparky” Rucker is keeping the legacy alive. In addition to being a storyteller and historian, he has been performing American folk music for about 52 years – traveling to various festivals and events across the region and internationally.

“I've done quite a lot in terms of trying to preserve Southern Appalachian music, and especially the African influence on that music,” Rucker said, adding that his research has revolved around trying to find the origins of the music and its long history rooted in African American culture and traditions.

“The music that comes out of the Black performers, the Black musicians, and the Southern Appalachia musicians is American music. It was created here in this country, not something that we brought in from some other place, but it was a blending of African and Native and Scott and Scott Irish and Irish music. And it's truly beautiful, unique music,” he said.

The beginning

Southern Appalachian music was born in bondage.

Various West African cultures, religions and languages were forced to merge in small spaces on slave ships, according to Atalaya Dorfield, a research assistant for the African American Experience Project at the Great Smoky Mountains.

“Even for exercise, they were forced to come on top of the ship on the deck and dance... for entertainment to the white crew. So that's where you start to see these Africanism start to merge,” Dorfield said.

The African American Experience Project is working to document the history of African American people in the Smokies. Dorfield said enslaved Africans were first brought to East Tennessee as early as the 16th century.

Southern Appalachian music was created when different cultures intertwined, she said. Native Americans and Europeans were also on those ships with Africans – causing the merging of different practices and sounds.

Once those people were in what is now the United States, the music started adapting and changing depending on where they were geographically and who was living there.

“African American culture, music began on slave ships, because they were forced to kind of communicate for us to combine languages, religions and cultures,” she said, adding that once they were dispersed throughout the country that’s “when we start to see different things develop and evolve.”

“It's definitely an intercultural genre,” she added.

In the late 19th to mid 20th centuries, the railroad industry spread Southern Appalachian music even further, prompting even more nuances of the sound to emerge. During this time, many African American people from the deep south moved to the Appalachian region for jobs.

“There are a lot of different stories of people like on breaks, or just whatever living arrangements that they had for them, playing music,” she said.

Some people also traveled to northern states, still bringing Southern Appalachian music with them. As it spread, and new genres were developed like folk and country, the African American influence became less visible.

“The record industry in the 20th century did not want Black people playing that music. They thought it was white music and they call black music ‘race music’ and align that with jazz and with blues,” she said.

The sound

Southern Appalachian music features several distinct sounds and unique playing techniques that come from African traditions.

The banjo is one object that serves as an example of this history.

Derived from multiple West African gourd stringed instruments, a five-string banjo has four melody strings in one drone string. The drone string is the short string at the top. It never changes, whereas the melody strings allow the musician to play notes depending on finger placement.

Now a distinct sound in other genres like folk and country, the banjo was one of the things that came with enslaved people to the United States, Dorfield said. Even the downward stroke playing style was started by enslaved Africans.

“Once they got here, that's when you start to see them take on other European stringed instrument characteristics, but the basics of the banjo,” she said, adding that this one instrument shows how people took what they knew, and through intercultural practices, adapted it depending on the geographic location.

Rucker said the banjo and how it is played also served as a point of commonality between different groups of people.

For people from Ireland, their main instrument was the bagpipe. Similar to a banjo, it has four drone strings and then a “chanter” that plays the melody,” Sparky Rucker said.

“All of the sudden you see these cultures have similar music,” he said. “They started listening to each other and looking at the instruments and ‘oh my gosh, that’s basically being played the same way,’ and all of the sudden, the rest of the week you would see them trading instruments – let me play your banjo, let me play your ngoni, let me play your angklung, which is another similar instrument,” he said.

The banjo went through various changes, eventually becoming the instrument that we hear in various genres of music today.

The fiddle is another key sound.

"When you play a violin, you know, you tuck it under your chin and you play the precise notes and you play everything that Bach or Beethoven wrote. But the fiddle a lot of times they were actually playing on their arm as opposed to up against their chin," Rucker said.

Keeping the history alive

Today, researchers and historians, through efforts like the African American Experience Project in the Smokies, are looking to document this history. While music is just one facet of the initiative, the project’s goal is to educate visitors about the presence of African American people in the mountains and East Tennessee.

Dorfield said oftentimes when people think about Southern Appalachian music, the African American influence is not mentioned. In fact, it wasn’t until the mid to late 20th century that people started to acknowledge Black people were in these spaces as musicians, she said.

“A lot of that is because historians, when they were looking into Southern Appalachia music, and ballads and things like that, they looked at the European roots and not the African roots,” Dorfield said. “We know that this is a big part of the narrative but the stories aren't told.”

This idea of invisibility is a reason why the Smokies are spearheading initiatives to research and tell this history, Antoine Fletcher, the science communicator for the Appalachian Highlands Science Learning Center said.

“I think about all the great creativity that was lost because of this invisibility because African Americans for so long, did not pick up these instruments or these spaces were inviting to them,” Fletcher said.

He said teams have been researching since 2018, compiling a deep dive of records and personal stories.

“We want to make sure that when people come through the gates, or the trees or wherever of the Smokies, that they're not only finding the history of early White settlers but also African Americans as well, and it inspires them to advocate for the park,” he said. “Then we foster stewardship with these new audiences and so this project is very challenging, but that is that's a great thing.”

The next step is to get all of this information to visitors. Fletcher said they plan to install panels and exhibits throughout the park that tell these stories. He said they want it to be a way for people to engage with history and learn new things.

They are also planning a series of town halls to share information with people, Fletcher said. He hopes this prompts community members to come to them with more information.

“I think this project is a trailblazer for many projects to come in the National Park Service,” he said, adding that the effort to continuously document history will go on for years to come.

While making the invisible history visible again is the main goal, Fletcher and Dorfield also hope their research builds relationships with people of all backgrounds.

“I didn’t grow up going to national parks,” she said. “Just thinking about how this project can connect African Americans with a park itself because nature is for everybody to enjoy, and just making national parks become something that first comes to mind with African Americans who are going to go on vacation and knowing that they're a part of that history as well.”

Telling this history that was ignored for so long is something Sparky Rucker is also working to do as a musician himself.

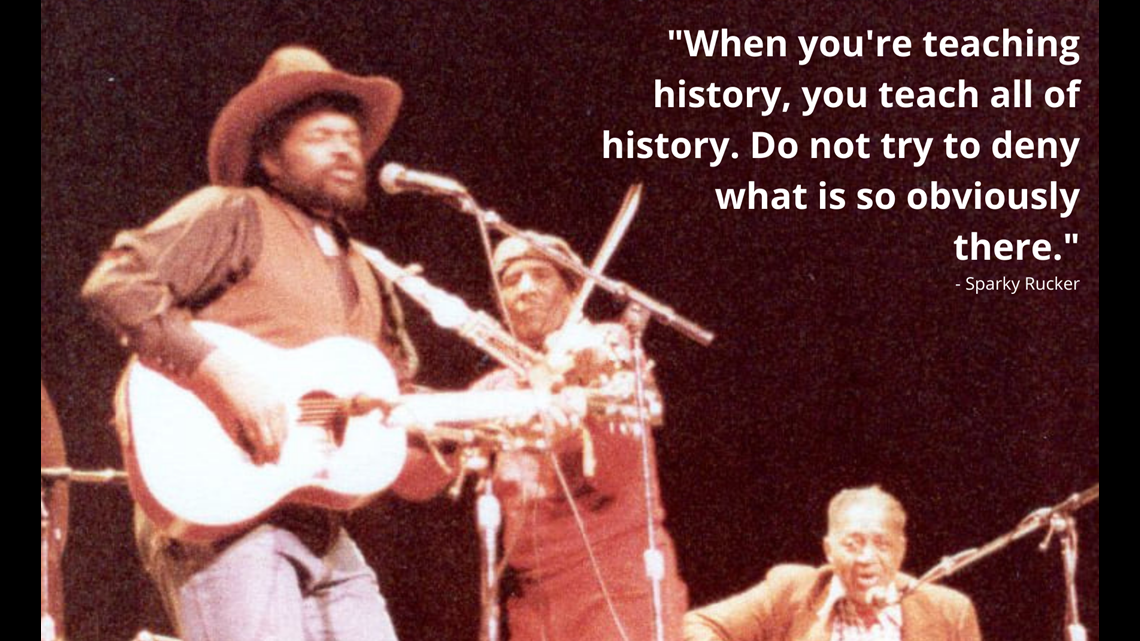

“There's this been this problem of people trying to deny the history of this country,” Rucker said.

“When you're teaching history, you teach all of history. Do not try to deny what is so obviously there,” he said. “We don't deny it because people that don't know their history are in danger of repeating the same mistakes.”

Rucker is also making it his mission to keep the music alive.

He started as an art teacher in Chattanooga, but now, he and his wife Rhonda teach classes to help mentor the next generation of musicians and artists.

“There's a whole bunch of young banjo players and fiddle players out there that have learned from these camps. It's been a blessing for us," he said.

If you are interested in learning more about the African American Experience Project, or you have a personal story you would like to share, you can visit their website here.