Beyond History: Knoxville's Black Experience - Past

We're highlighting stories that played an integral role in the foundation and development of African Americans in East Tennessee.

Black History Month is a time for people to honor and focus attention on African Americans who made contributions and sacrifices that helped shape the nation.

East Tennessee has many stories of how African Americans made improvements within its region.

From when the enslaved were freed to civil rights protests in downtown Knoxville to how the musical origins of African Americans influenced Appalachian music, there is so much history that is explored.

This is the journey through East Tennessee's Black history.

Emancipation Day

On Aug. 8, 1863, a group of enslaved African Americans in Greeneville were freed from their enslaver, Andrew Johnson.

Today, the 8th of August is known as Emancipation Day and is a day of celebration, remembrance and reflection of that moment in Tennessee history.

Aug. 8 will forever be remembered as a day of freedom in East Tennessee.

Underground Railroad

Over 16 decades have passed since Harriet Tubman helped the enslaved to freedom along the underground railroad, and one of those stops was in East Tennessee.

In 1862, Friendsville resident Wilson J. Hackney used a cave on his property, known as Cudjo's Cave, to help those who wanted to escape slavery.

He furnished the cave with enough supplies, food and bedding for up to 50 people at a time. During its use, Hackney's cave helped over 2,000 people on their way up north.

Red Summer

1919 was the year of high racial tension in Knoxville and led to what we now know as "Red Summer." Riots spread through the city's Black community and it all started when Maurice Mays was arrested for a crime some say he didn't commit.

"The story goes that supposedly there was this African American male has killed this white female," said Renee Kesler, Beck Culture Exchange Center president.

Mays was a former deputy sheriff and politician in the early 1900s. He also dabbled in gambling and bootlegging, which raised the anger of local police officer Andy White.

In August 1919, an intruder entered Bertie Lindsey's home and murdered her in her bed.

"[Bertie's] cousin who was staying with her at the time said a Black man did it," said Robert Booker, a Knoxville civil rights activist.

Soon, a mob of angry white people gathered outside of the jail where Mays was being held. A few were able to break in and searched for him but were unsuccessful.

Many businesses in Knoxville's Black neighborhoods were destroyed and the National Guard had to be brought in.

By the end of the riots, there were hundreds injured and seven people were dead. Six were Black and one was white.

"As history records, it becomes one of the bloodiest, most violent parts of our history, with respect to race relations," Kesler said.

Mays was sentenced to death by an all-white jury and died in the electric chair on March 5, 1922.

Civil Rights Movement

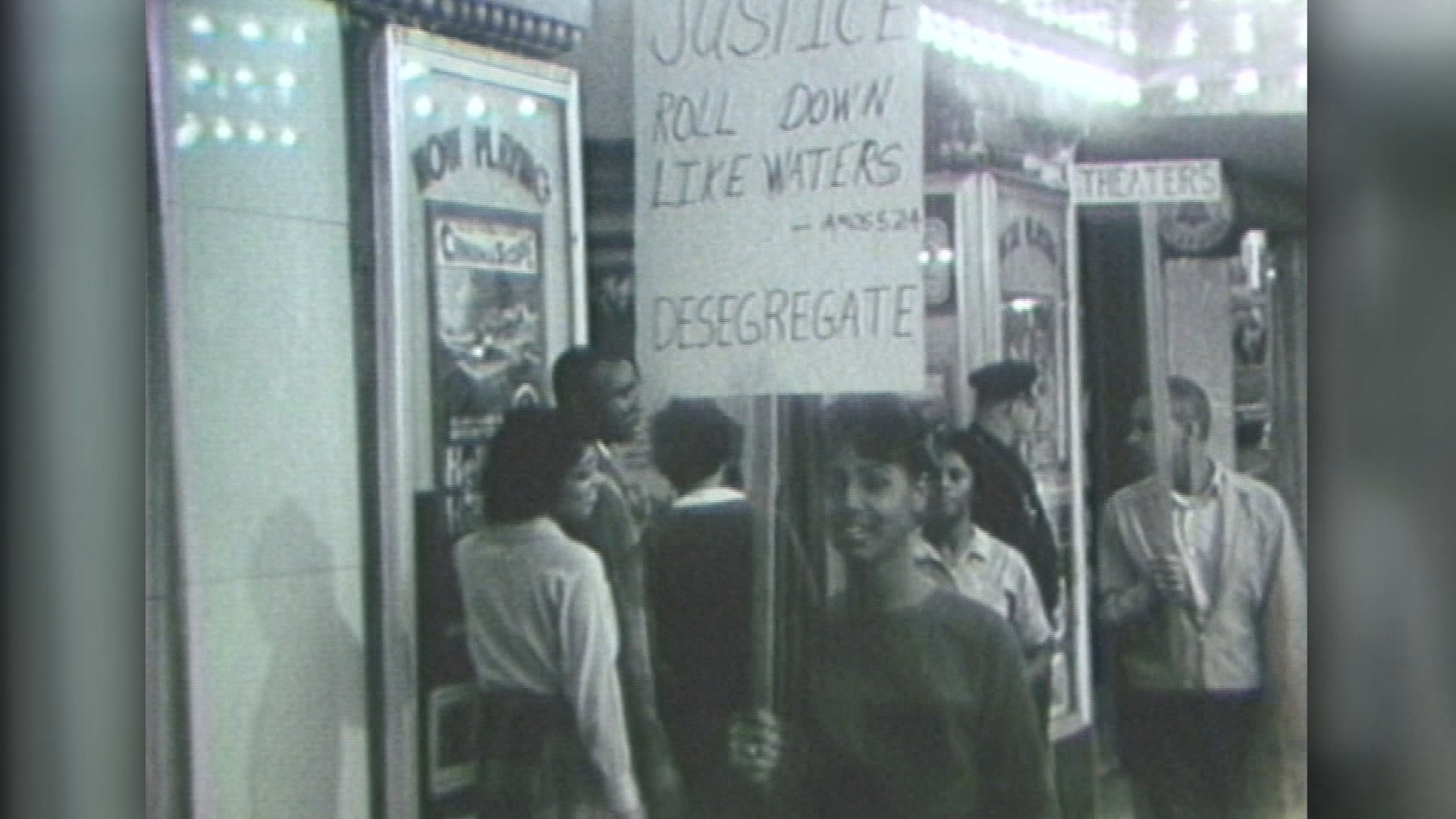

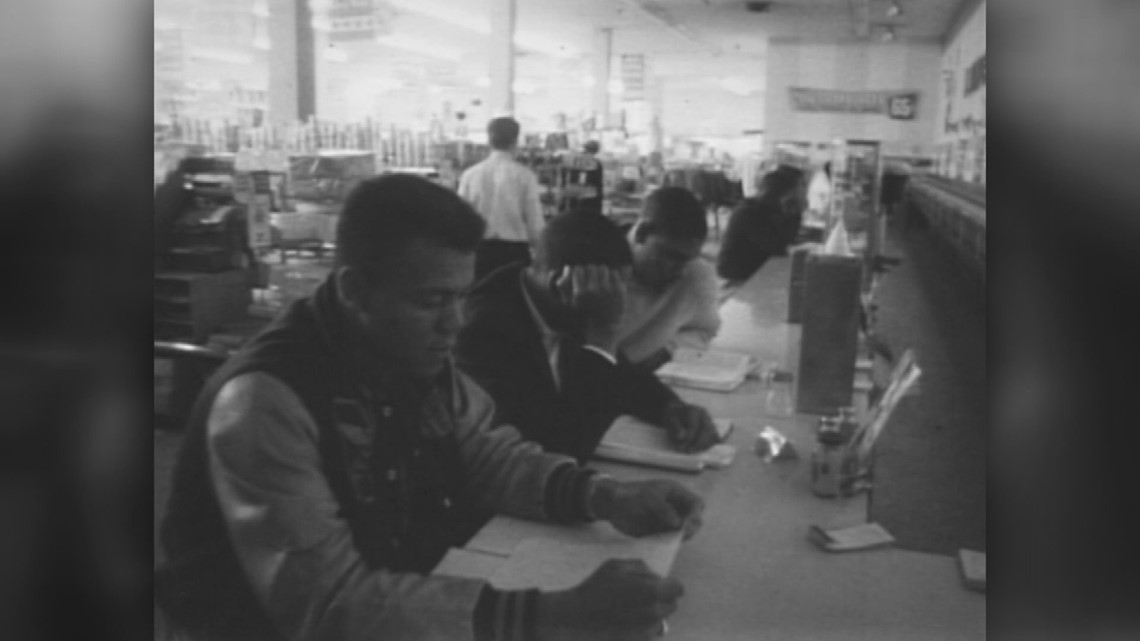

The height of the national civil rights movement happened in the 1960s right here in Knoxville.

Although public schools in Knoxville were being integrated, African Americans were still denied access to theaters, restaurants and other businesses downtown. This was where protests were concentrated.

One of the leaders of the demonstrations was Avon Rollins who later marched through the South with Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

"We were students at the University of Tennessee. I was along Marion Barry and we joined forces with students from Knoxville College," said Avon Rollins, a civil rights activist. "Probably hundreds of people were put in jail as a result of the demonstrations."

Protests were also aimed at cafeterias and restaurants in the University of Tennessee neighborhood.

On July 5, 1963, theaters and restaurants and other businesses were open to Black people. This was a result of the realization by local merchants that African American customers would bolster business.

The Knoxville civil rights movement was for the most part orderly and failed to produce violence experienced in other parts of the South.

Notable Visits

In May 1960, Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. visited Knoxville College to share his words of wisdom with the graduating class.

One of the leaders of the Knoxville civil rights movement, Robert Booker, was present for the visit.

"It was one of the most fascinating speeches I'd ever heard," Booker said. "Dr. King told the class, 'You're now graduating, and you're getting ready for the world of work. Remember when you go to work to do the best you can. If you become a teacher, teach like Shakespeare wrote plays. If you become a doctor, practice like Beethoven wrote symphonies. Even if you are a street sweeper, sweep streets like Raphael painted pictures.'"

The speech brought encouragement to Black men and women who lived in a deeply segregated city.

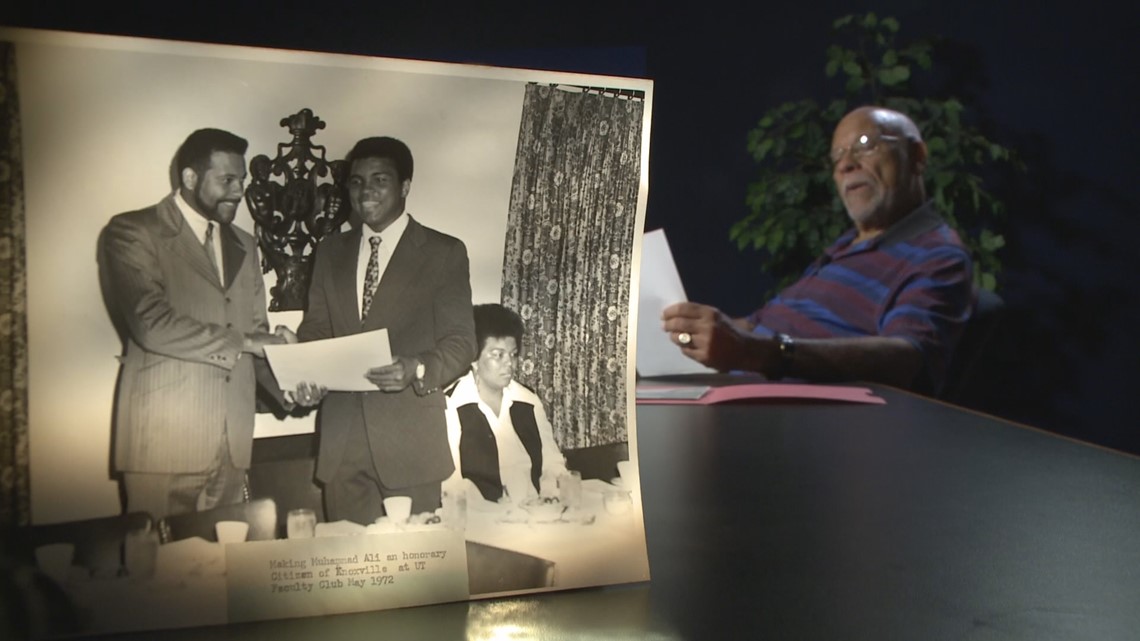

Booker was also present when Muhammad Ali visited the city in the '70s.

To welcome Ali to the city, Booker prepared a poem to present during a speech at the Black Student Union at the University of Tennessee.

Part of the poem reads:

On behalf of the mayor and the people of Knox, I salute the greatest of all those who box.

And so we in Knoxville affix our official stamp in welcoming this man who is truly the champ.

He wanted to surprise Ali and according to Booker, it worked.

"[Ali] said, 'Who wrote that?'. I said, 'I did.' He said, 'Can't nobody write poetry like that but me,'" he said.

Booker said he admired Ali for his commitment to his faith. Ali was stripped of his title for not enlisting in the military because it went against his religion.

"He was a true hero. He, like Martin Luther King, put himself on the line," Booker said.

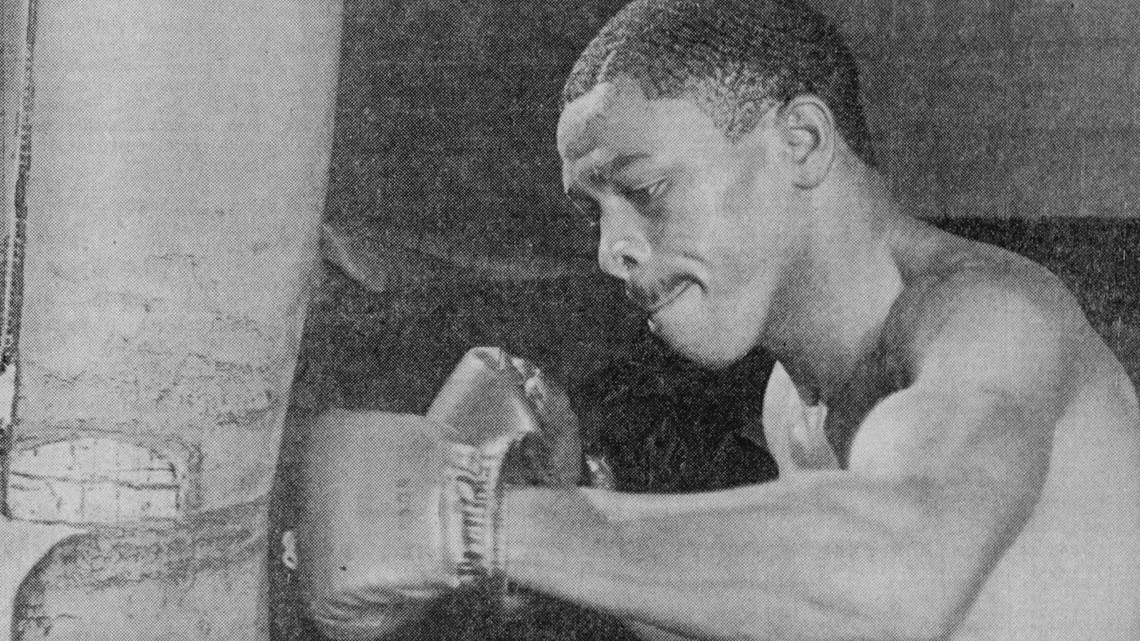

Frankie Randall

From one boxer who visited East Tennessee to one who made it his home, Frankie "The Surgeon" Randall, who grew up in Morristown, was a three-time world champion.

Randall was a standout amateur boxer who turned pro in 1983. Over the next 11 years, he tallied up an impressive record of 48 wins, 2 losses and 1 draw.

In 1994, he earned the opportunity to fight for the WBC Light Welterweight Championship of the World against undefeated Julio Cesar Chavez, who boasted a record 89 wins, 0 losses and 1 draw.

On that night in the MGM Grand Arena, Frankie Randall became the first man to defeat the legendary Chavez and won his first world championship in the process.

He went on to win the WBA Light Welterweight Championship on two occasions and would retire in 2005 after over two decades in the ring.

Randall died in December 2020, but his life and contributions to the sport of boxing will not be forgotten.

Music Origins

The musical origins of African Americans go back to the late 18th century and it started with a single-stringed instrument.

"Some of the very first evidence of documented Black music in Appalachia happens to be the presence of banjos on riverboats that came up the Tennessee river in the Knoxville area," said Dr. Ted Olson, East Tennessee State University professor of Black Appalachian music.

The African American influence on Appalachian music dates back to the 1790s. The sounds of the banjo led to the introduction of what we know as the blues ballad.

"They were story songs introduced by African American musicians, often telling stories based on prominent African American figures in the community," Olson said.

By the 19th century, the banjo had been adopted by white people and used in minstrel shows, which were quickly becoming the premiere form of entertainment across the country.

Although the instrument became appropriated, the Black influence continued to be present in the performances.