Back to Brushy Mountain: the historic prison's past and future

The WBIR series "Back to Brushy Mountain" examines more than a century of history and the future of the fabled prison in Morgan County, Tenn.

Update, May 13, 2018: If your device or WBIR app is not displaying the full article and videos (for example, some devices only show the first four paragraphs), click HERE. This will give you the best story experience with parts 1-5 of the series and all SideBar videos posted as chapters for easy navigation. All videos for the series can also be seen HERE as a YouTube playlist.

(MORGAN COUNTY) Around 40 miles northwest of Knoxville, men who were stripped of their freedom dug into the hills and built a place once referred to as “the worst thing in the state” of Tennessee.

Brushy Mountain State Prison operated for 113 years before shutting down in 2009. In that time, it carved a place in the nation’s culture of crime, punishment, violence, and labor.

Now the bars of the vacant prison will shift from serving hard time to serving hard liquor. Developers say the prison should open as a moonshine whiskey distillery and tourist attraction within a few weeks.

Profiting from the prison brings the history of Brushy Mountain full-circle. The main reason the prison was created in the 1890s was for the state to make money. But the financial decision to build Brushy Mountain only came after a bloody battle between free Tennesseans over the state's previous system of cashing in on convicts.

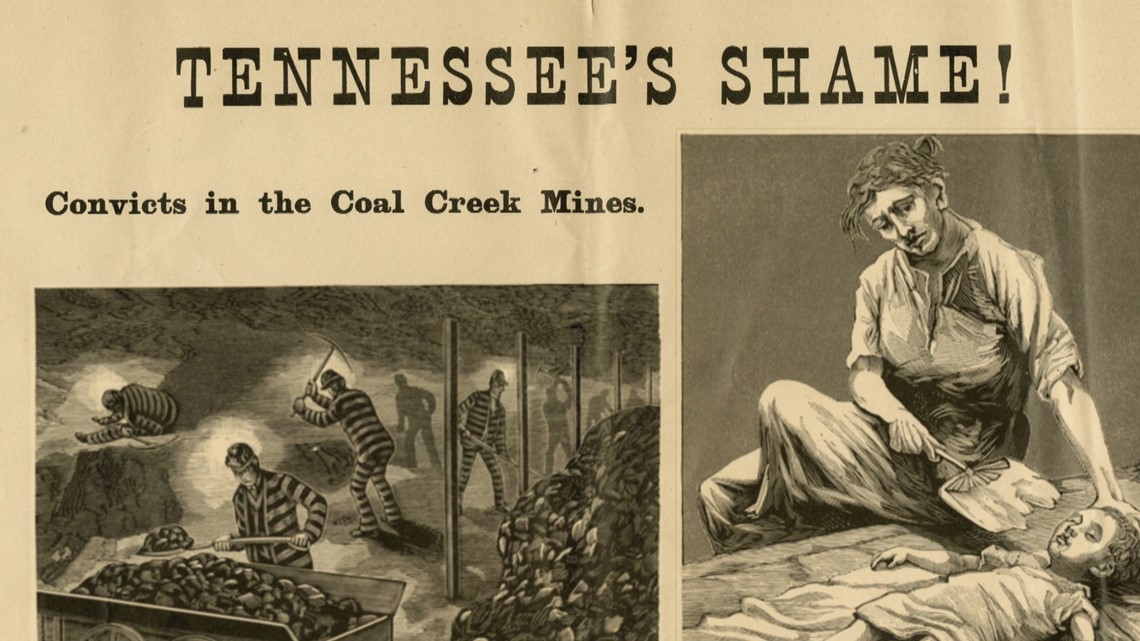

Convicts and Coal

After the Civil War, Tennessee and other southern states were broke. So, convicts were for rent.

The state leased inmates to private companies for mining coal and other hard labor. The system made the government money. It also saved money because the state did not have to build prisons. Coal companies built their own stockades to hold inmates near the mines and profited from cheap labor.

"It was probably a good system in the beginning, but by the 1890s the system had gotten corrupt," said Barry Thacker with the Coal Creek Watershed Foundation.

Leasing convicts essentially turned inmates into slaves at a deadly job. Most inmates had no mining experience and working conditions were awful. The state labor commissioner in the 1890s inspected the convict mines and wrote, "It is shameful to think that any class of men, whether free men or convicts, are compelled or allowed to work within" the mines.

The brutal form of de facto slavery brought another injustice to East Tennessee. Inexpensive convict labor took the jobs of free coal miners. The conflict boiled over in the Anderson County town of Coal Creek. Coal Creek has since changed its name twice, first to Lake City and now to Rocky Top.

The community was named Coal Creek when free miners fought back against convict-leasing. In 1891, the miners raided prison camps, tore down stockades, loaded guards and inmates on a train, and sent them out of town. They made it clear that convict labor was not welcome in Coal Creek.

The coal companies sent the inmates back. Governor John Buchanan sent troops to protect the prison camps. It was a showdown.

"This was a real moment in history. Free miners in Tennessee faced the state's militia in armed battle," said Bob Fulcher, a park ranger and founder of the Tennessee State Parks Folklife Project, during an interview with WBIR's Heartland Series.

Miners and militia fought each other in the Coal Creek War through the fall of 1892. The troops eventually won the battle, but miners won the war of public opinion. The controversy cost Governor Buchanan any chance at reelection. National publicity cast shame on the system of leasing convicts. The new administration banned renting convicts to private companies.

"The miners lost the final battle, but they won the war when the state abolished convict-leasing," said Thacker.

Without convict-leasing, the state government would lose a large source of revenue and incur the expense of building prisons to house inmates. The state’s solution was to mimic private companies and mine coal for itself.

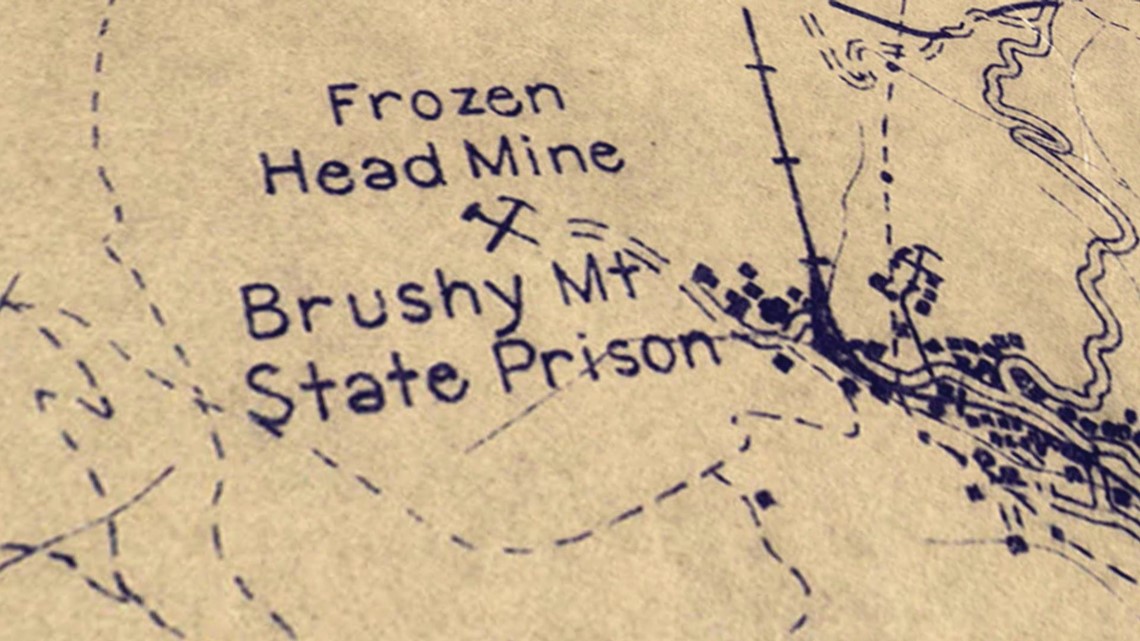

Geology experts inspected several locations across the state and recommended buying the land beside the small town of Petros in Morgan County because "there is no better coal property in the State of Tennessee."

"The state decided to cut out the middle-man. It was state efficiency at its finest. Coal was a valuable resource during the industrial revolution with steam-powered engines and a big demand for steel in cities across the country," said Joe Nowotarski, park ranger and historian at Frozen Head State Park.

"It turned out to be a money-making venture for the state," said Thacker. "Rather than leasing convicts to work in someone else's mine, they built Brushy Mountain State Prison and coal mine and used their own prisoners to mine their own coal. They had their own coke ovens to turn it into coke for making steel."

The state would not go back to being broke. It would force inmates to perform back-breaking work for profit.

Inmates laid the railroad tracks to the brand new Brushy Mountain State Prison, constructed a four-story wooden prison barracks, and started digging for underground riches in 1896.

None of the inmates at Brushy Mountain were on death row. Yet, doing time at Brushy was often a death sentence.

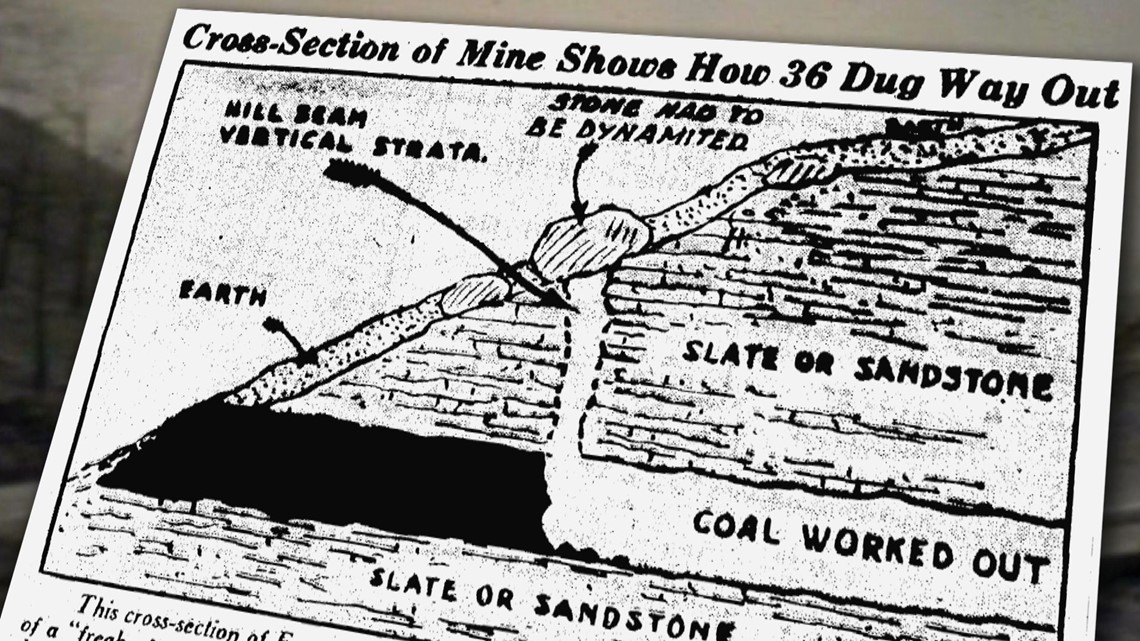

"At the Frozen Head mine, the coal here was very high in methane. That means it is very explosive. You hit one of those explosive pockets and boom. The whole thing will go up," said Nowotarski. "Geologically, I would not want to be digging or tunneling in this area. In addition to the explosive component of coal, the area has a mix of sandstone and shale. Shale is brittle and wafer-thin. Sandstone is very sturdy. You had a mix of strong rocks, explosive coal, and shale that easily crumbled. It was a recipe for disaster and cave-ins."

It was a difficult job in a treacherous location performed by imprisoned men who often had no prior mining experience. Dozens of inmates died in mining accidents. Nonetheless, the state kept demanding the living to mine coal.

Inmates worked all day. If they stopped, they found painful motivation from a seven-foot leather strap. After a day of abuse underground, the convicts spent the night in an overcrowded disease-infested wooden building heated by fire.

If the coal mines and disease did not kill you, another inmate might. Murder was a common cause of death at Brushy Mountain State Prison.

"The mines were dangerous geologically and it was a very volatile work group. These are convicted criminals you are forcing into a hole together," said Nowotarski.

In 1932, former Brushy Mountain prisoner Rex Cosby of Memphis wrote a series of newspaper articles to shed light on the horrific conditions at the prison. The white-collar criminal went to prison for forgery, but found the fortitude to put his real name on the byline of scathing articles that would undoubtedly result in retribution if he was ever imprisoned again.

Cosby wrote about how the prisoners worked in sludge, ate unrecognizable slop, and had to steal food and blankets to survive the cold nights in the prison. Those who survived were destined to endure the slavery that came with the next sunrise. Cosby said floggings were frequent, inmates were “driven like animals,” and he named 13 men who died during a 15-month span at the prison.

Other former inmates publicly verified Cosby's story. A World War 1 veteran from Corryton who served time at Brushy said he would rather go over the top of the trenches during battle in Europe than go back down in the mines at Brushy.

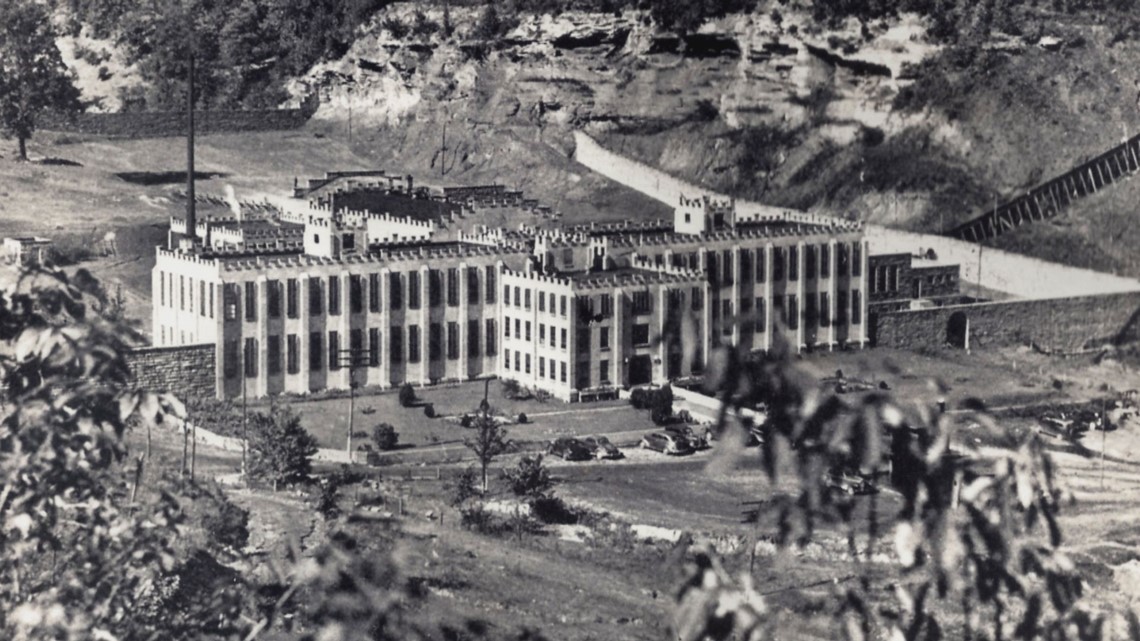

The articles captured the attention of clergy, the women’s league, and politicians. When the state’s new commissioner of institutions inspected Brushy Mountain, he called the wooden building a fire trap and described the overall prison as one of "the worst things in the state."

Improvements were on the way in the form of a fire-proof building constructed of sandstone. In the mid-1930s, the current fortress-like building was completed. It offered improvements in safety, sanitation, and possibly salvation.

"If you look at the building from overhead up top, you can see it is in the shape of a Christian cross," said Nowotarski. "That was to 'just give them some Jesus,' for lack of a better term. They wanted to moralistically reform these people incarcerated at Brushy."

The improved facilities may have been a relative slice of heaven, but Brushy remained a violent hell for prisoners.

Inmates kept killing inmates. On a couple of occasions, guards killed fellow guards. The mines remained a death trap. The cave-ins continued and so did the beatings.

Some guards made money on prisoners by accepting bribes for better treatment. A state investigation in the 1930s found some guards simply stole from inmates. American Legion bonus payments to prisoners who were World War 1 veterans were often intercepted and cashed by prison workers.

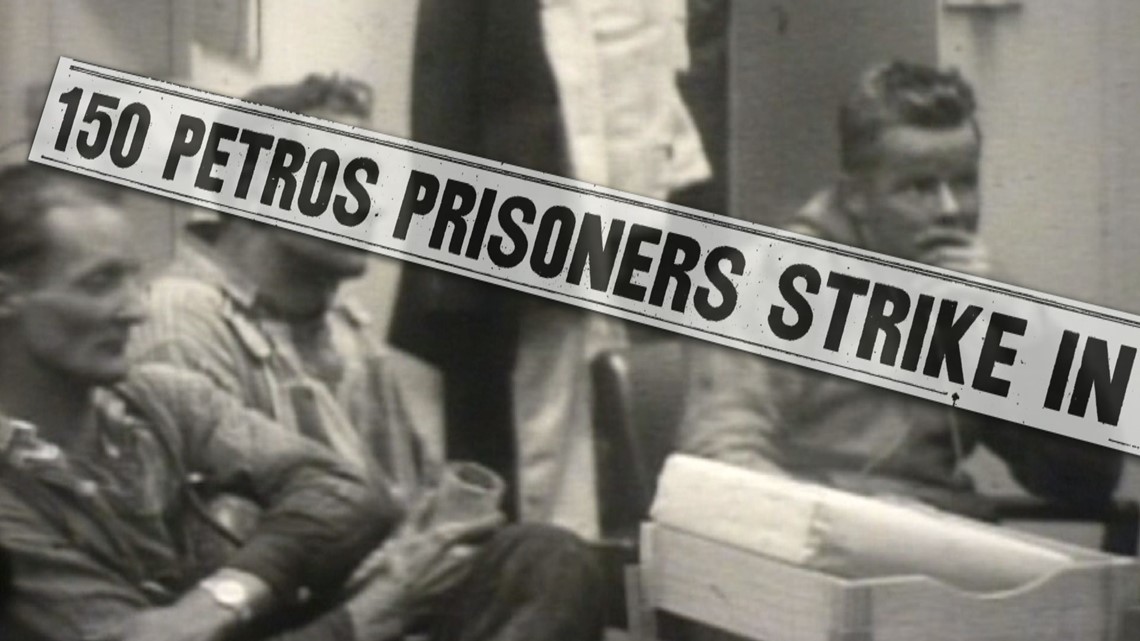

Prisoners who took all they could stand had one main method of standing up for themselves. They went on strike and refused to work.

You can force hundreds of inmates down in the mines with a few guards, but you cannot easily or quickly force them out. Prisoners organized strikes in the mines to force the authorities to acknowledge their complaints.

At least half a dozen times from the 1920s through the 1960s, inmates took guards hostage in the mines and refused to come out until their grievances were heard.

The prisoners who made trouble paid a painful price. The state doled out lashings to the leaders of prison strikes.

A Knoxville News Sentinel article from August 1933 states the leader of a strike was diagnosed as insane and shipped off to a mental institution. The article said the insanity diagnosis was based on a blood test.

The madness of the prison mines continued until the mid-1960s. That’s when another mine collapse killed a couple of inmates from East Tennessee who were convicted of relatively small crimes, far from deserving a death-sentence.

Aside from the accidents, the mines were no longer profitable for the state. The last lumps of Brushy Mountain coal came out of the ground with the inmates in 1966.

The mines were closed for good, but what do you do with all the inmates? Idle hands gave crowds of stir-crazy convicts more time to do the devil’s work and plot ways to escape.

Everyday Escapes

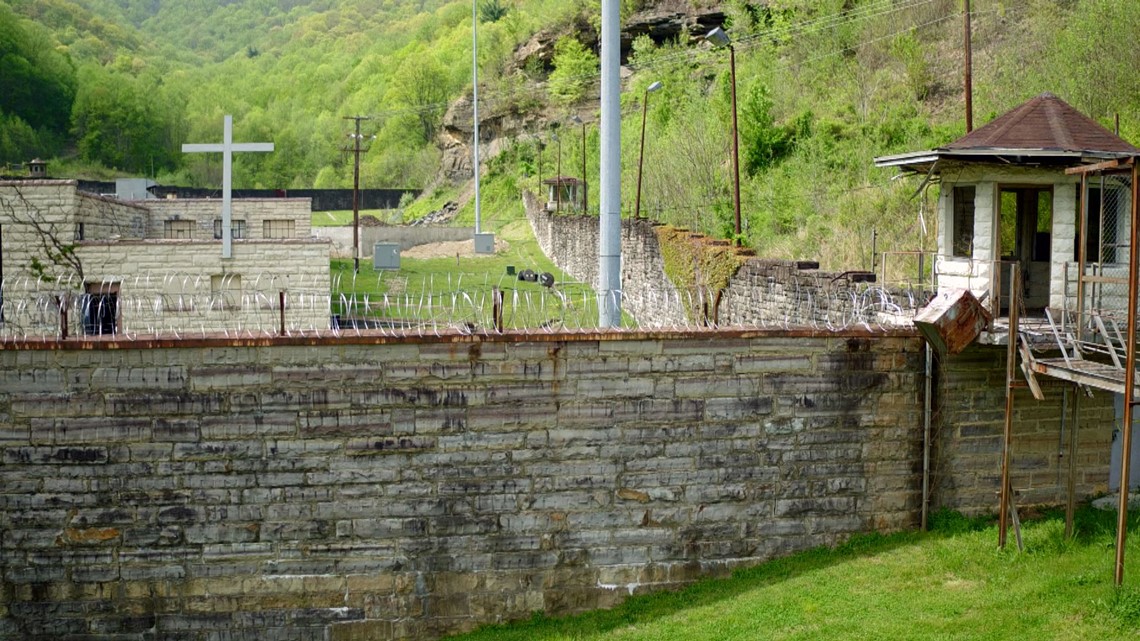

Brushy Mountain Prison's high stone walls and the surrounding horseshoe of rugged hills have given the prison the reputation of a place impossible to escape without eventually being recaptured. Some wardens and media reports touted Brushy Mountain as "Tennessee's Alcatraz," comparing its physical barriers to the famous island prison in San Francisco.

The boasts of Brushy as a historically secure site are simply not true. People escaped from Brushy Mountain State prison all the time. However, the mountains and terrain are definitely an obstacle.

"The mountains are more of a prison than the prison is. There is only one way in and one way out, and that is through the mouth of the valley through Petros. Of course, many people have tried to escape by going over the mountain and that did not fare well for most of them," said Frozen Head State Park ranger Joe Nowotarski.

Escapes were a regular occurrence because inmates were not always confined to cages behind stone walls and barbed wire. They were constantly moving back and forth between the main prison site, the prison's farm a few miles away, the coal mines, and courthouses.

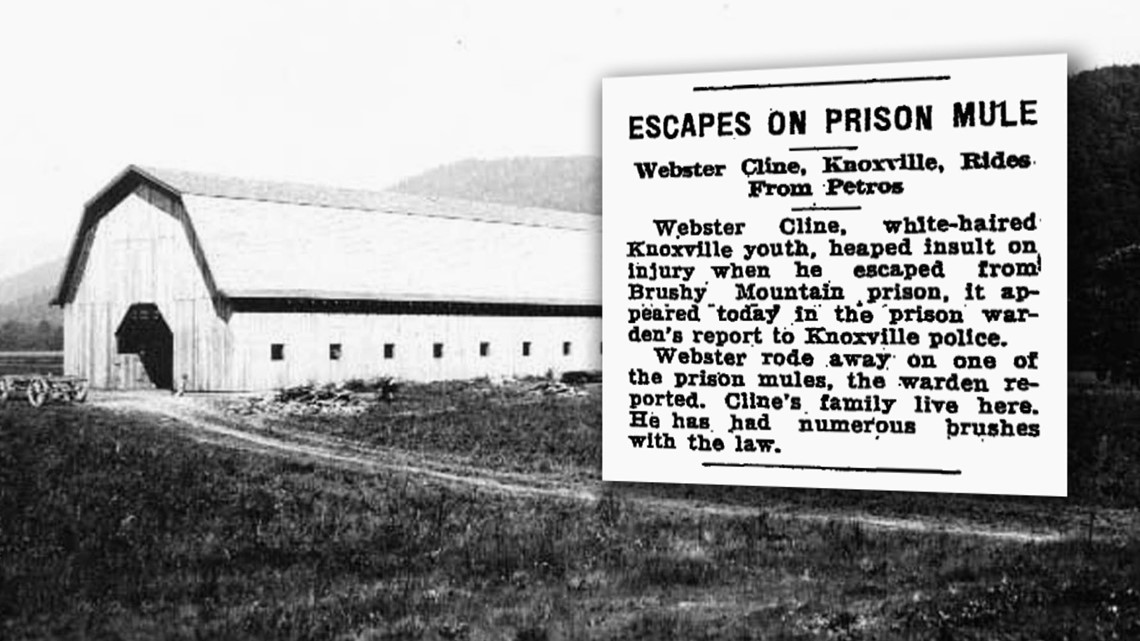

A search of newspaper archives from 1922 to 2009 reveals hundreds of reports of escapes and "killers on the loose" from the prison in Petros. The escaped on foot. They stole cars. One report from August 1931 says a Knoxville man was on the lam from Brushy after stealing a mule.

The inmates did whatever they could to get away from the abusive environment and a deadly job in the coal mines. The job involved going deep underground and blasting coal free with dynamite.

In 1938, the prisoners in the mines blasted their way to freedom by tunneling to the other side of the mountain. A total of 38 convicts were suddenly on the loose and many were armed with dynamite from the mines. Most were quickly recaptured within a few days, sometimes by average citizens. One article tells the story of "Uncle Ike," a man in his 60s who was at home sick with pneumonia when he encountered four inmates and held them at gunpoint until the authorities arrived.

Some families who lived in Morgan County tell tales of a different approach to fugitives. When they learned a prisoner escaped, they would put a meal and a change of clothes outside the home, go inside, and lock the doors. If a desperate inmate came across their property, the food and clothes would hopefully provide enough resources for them to keep moving instead of potentially robbing the home or taking hostages.

Fugitives from Brushy Mountain committed violent crimes against innocent people. One of the notorious stories involves William Tines, a black man from Knoxville. He broke out of Brushy, broke into a home in Harriman, and raped a white housekeeper. He was sentenced to death and executed in the electric chair in 1960 for the rape conviction. On a side note, although his guilt was never in doubt, the Tines rape trial was filled with unjust irregularities during an era of racial prejudice. For example, some members of the jury were also witnesses who testified against Tines.

Throughout the 20th century, prison guards and officers were killed trying to recapture escapees. In some cases, the prisoners obtained their brief freedom by killing guards.

In 2005, Brushy Mountain prisoner George Hyatte was at the Roane County Courthouse when his wife shot and killed longtime guard Wayne "Cotton" Morgan. Morgan was a popular guard who was just a couple of years from retirement. The Hyattes escaped the courthouse and were captured the next day in Ohio. The Morgan County Correctional Complex honors the slain guard's memory in many ways. The road to the prison was renamed Wayne Cotton Morgan Drive and a stone marker was placed beneath the prison's flagpoles.

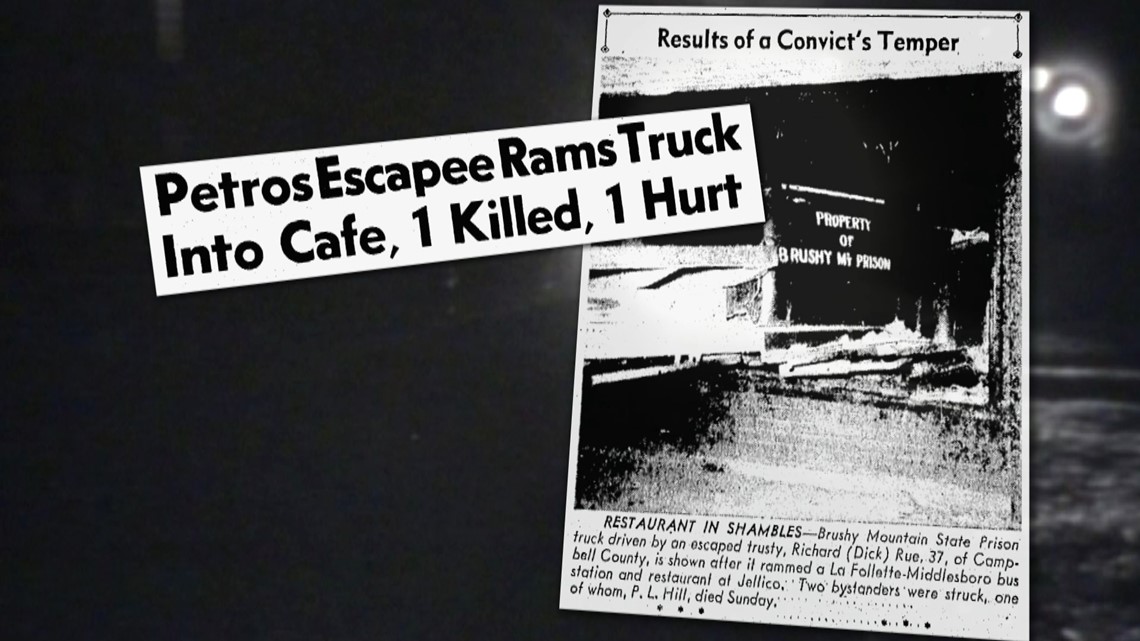

Inmates did not always have to make daring or violent escapes. Many fugitives were minimum security inmates whose good behavior earned them jobs as trustees. Trustees could perform jobs such as driving prison vehicles off-site as well as operate heavy machinery not entrusted to other convicts.

The temptation to take off was too much for many trustees to resist. They would simply drive away in prison vehicles and not return as scheduled.

Family members often made public statements asking fugitives to turn themselves in. Sometimes, the motivation for a prisoner to escape was to settle family affairs.

In 1950, a trustee learned his wife wanted a divorce. He sped in a Brushy Mountain Prison truck to his hometown of Jellico and drove through the front wall of the restaurant where his wife worked as a waitress. Instead of killing his wife, the crash killed a World War 2 veteran who was eating lunch.

The escapes and their conclusions could be dramatic. Other times, the prisoners surrendered peacefully.

"People would do anything to try to escape. One night, some guys took sheets and knotted them up [into ropes] and fixed it where they could swing it over steam pipes and climb out," said former inmate Robert Gibson during a recent visit to the vacant prison. "When they were climbing out, the pipes broke and the guards ran in. One of the guys immediately surrendered and said, 'Don't shoot! Don't shoot! You can't blame a man for trying.'"

Some inmates turned themselves in without being cornered. In 1932, a homesick convict escaped through the mountains with hopes of spending the holidays at home in South Carolina. After a couple of exhausting days dredging through the unforgiving terrain, he found local officers, turned himself in, and said he "preferred to spend Christmas in prison" at Petros.

The exhausted inmate in 1932 is hardly the only person who managed to beat the prison's walls, but was unable to beat the mountains. The same can be said of James Earl Ray, the man who killed civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

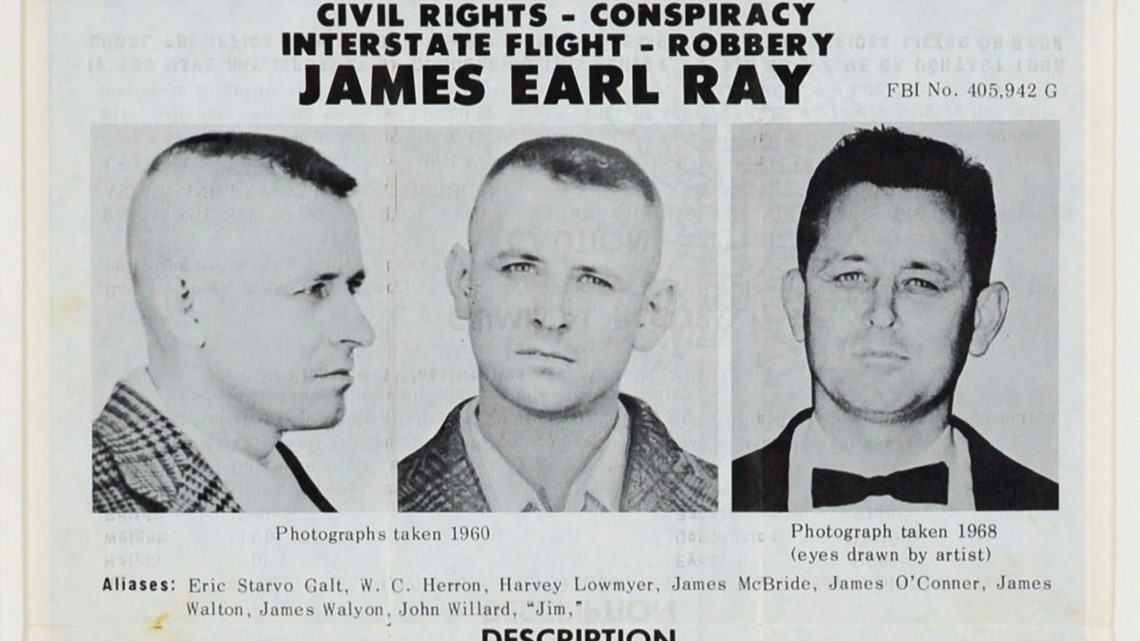

James Earl Ray's fame and infamy

When Brian May with Brushy Mountain Group takes people through the old prison, there’s usually one question he cannot escape.

"What I get asked all the time is which cell was James Earl Ray's. The real answer is he didn't have a single cell. Because of who he was, they had to move him around quite a bit. He was never in the same cell for very long, for his safety."

James Earl Ray was a fugitive who escaped from prison in Missouri when he shot and killed Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at a hotel in Memphis in April 1968.

Ray escaped the country, but was caught in England and brought back to the U.S. Then he escaped the death penalty by pleading guilty to murder.

Just a few days after he was sentenced to 99 years in prison, Ray claimed he was innocent and wanted a trial. He claimed he was lying and was coerced when he pleaded guilty. Of course, he had nothing to lose by requesting a trial because double-jeopardy rules protect defendants from receiving a harsher sentence than the original conviction.

In 1969, Ray was sent to prison in Nashville. He stayed there around a year and complained about being kept in isolation for his own protection.

In March 1970, Ray was moved to Petros at Brushy Mountain State Prison. The warden at the time, Lewis Tollett, told the media there was no reason to worry about Ray ever escaping. Ray was “just another prisoner” and Tollett claimed only three people ever made it over the wall during his time as warden and all three were quickly recaptured.

When Ray arrived at Brushy, he almost immediately began plotting an escape. Before his days at Brushy were done, he attempted at least four escapes.

On May 3, 1971, Ray removed a concrete block from his cell, climbed through an air vent, sawed through bars, and made it to a concrete tunnel that went 100 yards outside the prison. The plan was foiled because the tunnel went to the steam plant with 400-degree heat that melted the scheme.

In February 1972, guards caught Ray crawling in an area where he could not be seen and carrying a makeshift handsaw to cut a hole in the ceiling.

Ray got out of Brushy in 1972, but it was not an escape. He and the rest of the inmates were relocated to Nashville because a labor dispute and guard strike shut down Brushy Mountain Prison for almost four years.

By 1976, Ray and the other inmates were back at Brushy. Ray continued to claim he was the victim of a conspiracy and wanted a trial. He said he was framed and could provide information to prove the FBI killed King.

During his life, Ray convinced many people of various conspiracy theories. That includes the King family and many of his fellow inmates.

" I would not say James Earl and I were best friends, but we were associate-friends during our time in prison,” said former inmate Robert Gibson. “James Earl was a loan shark in prison. Everyone was involved in something and that was what he did. He’d loan you $1 for a $1.50 and that kind of thing. He was just a good guy to be around. An ordinary everyday guy who was very polite. I don't believe he did it [killed King]. I believe the FBI, TBI, and all those people had it all set up to point to James Earl Ray."

Some expressed a belief Ray was involved in King’s death, but that he did not act alone and may have been part of a larger effort by government agencies. Others said Ray was completely innocent of the crime and did not shoot King. Most law enforcement and investigators, including multiple reviews through the decades, firmly conclude Ray was a racist who believed there was money to be made killing civil rights leaders.

Before he was charged with King’s murder, Ray’s criminal history primarily consisted of being an error-prone thief. His previous ineptitude fueled a belief among many that he could not have managed to kill King on his own.

As momentum grew for a Congressional committee to investigate King’s assassination, Ray made his third escape attempt from Brushy.

On June 10, 1977, Ray and six other inmates made it over the stone wall through a gap in the electrical wire. They climbed over the wall with a 16-foot make-shift wire ladder.

Morgan County became the center of the media universe as a massive manhunt ensued for the escaped killer of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The FBI added Ray to its most wanted list and was part of the search.

The FBI’s involvement in searching for Ray immediately led to more conspiracy speculation. Ray’s former attorney, Robert Livingston, told WBIR he believed the government could have been behind forcing Ray to escape so they could justifiably kill him.

[ YouTube: WBIR James Earl Ray escape newscast June 11, 1977 ]

"There are people in the world, in my judgment, that would like very much for James Earl Ray to be dead so he cannot testify before the congressional committee," said Livingston on June 11, 1977.

After two and a half days on the run, the local boys and bloodhounds from Brushy Mountain State Prison sniffed ray out of the wilderness just a few miles from the prison. Ray was alive, but exhausted by his trek through the steep terrain.

"He had laid down, covered himself up with leaves, and the dog team walked up on him and took him into custody,” said Warden Stonney Lane.

All seven fugitives were caught by the next day. Then the prison officials began to catch hell over the escape. As WBIR journalist Steve Dean said during his report on June 13, 1977, “They have to answer questions like, ‘How do you hide a 16-foot ladder in a prison? Why was there no guard at the guard post nearest the escape point? And was there any outside help aiding the escape?’"

Prison guard Floyd Hooks said he grabbed his gun and began to run outside the guard tower when he tripped over his own rifle and accidentally locked the tower door shut. Warden Stonney Lane fired Hooks. A state commission gave Hooks his job back because although the guard was negligent, it believed prison officials were more negligent.

Warden Stonney Lane vehemently disagreed with the commission’s findings and told WBIR it was “a commission that came to this institution and spent five hours. And in that five hours, became experts on security measures in a maximum-security institution."

Ray finally got a trial, but not the one he wanted. He was tried and convicted for the escape from Brushy. The jury added a year to his sentence.

During the trial for his escape, Ray met WBIR courtroom artist Anna Sandhu and the two married.

"I plan to marry James. Because I love him and I like him, very much. He's very private and misunderstood," said Sandhu in a September 1978 report by WBIR’s Dustin Moody. Moody said to Sandhu, "But James Ray is a convicted murderer. How do you feel about marrying a convicted murderer?"

Sandhu replied, "Well, first of all, I know that James is innocent."

Sandhu had accompanied Ray during his testimony to Congress in August 1978. His escape in 1977 lit a fire for Congress to investigate King’s assassination before the man with all the answers could escape again.

"I feel that we have a moral obligation to Dr. King to see Ray. We need to know the role of the FBI in the assassination. The letter that Ray sent is evident that Ray was involved at some level and is now willing to share that information,” said civil rights leader Jesse Jackson in August 1978.

Ray testified in public for the first time since the King assassination. He was allowed one hour to read a statement and answer questions. He told lawmakers he was framed by a mysterious man named Raoul. His story went nowhere. Ray went back to Brushy Mountain.

In November 1979, Ray tried to escape for a fourth time. He and another inmate placed dummies in their beds, complete with human hair from the barber shop. Ray made it through a fan in the top of the building, sawed out of the roof, and climbed down the building. Guard Lorraine Robinson noticed someone sneaking along the wall.

“So, I got my shotgun, went out, fired my gun, and hollered halt. I had no idea [it was James Earl Ray]," said Robinson.

In June 1981, three inmates attacked Ray in the prison library. He underwent surgery for 22 stab wounds to the face, chest, and arms. He also suffered internal injuries from being beaten. The surgeon said it took 77 sutures to close the wounds, but “none of them were dangerous.”

Ray survived and the state moved him to the prison in Nashville. He came back to Brushy Mountain in 1987 and finished a book that claimed he was innocent.

In the late 1980s, Ray and Sandhu divorced. Sandhu later told a different story about Ray’s role in King’s death. Sandhu recalled, "I said, 'James, you sound like the kind of person who could have killed Dr. King.' And he said, 'Yeah, I did it. What if I did?'"

In 1992, Ray left Brushy Mountain Prison for good. He was relocated to Nashville. He died there

April 23, 1998. The cause of death was prolonged liver disease and kidney failure.

Long after his death, Ray's crimes, conspiracies, and attempts to flee Brushy Mountain State Prison live on as a main attraction at the new tourist destination. It’s a part of the prison’s history that will never escape Brushy Mountain.

Wickedness and Redemption

Robert Gibson is a free man. He was released from prison in 2011 and is no longer on parole. He treats life in "the free world" as a gift. He fully expected to die in prison.

"When I first went through those big steel doors out there, I thought to myself, 'What have I done?' I thought I would die right here at Brushy Mountain Prison. This is where they sent all the violent prisoners."

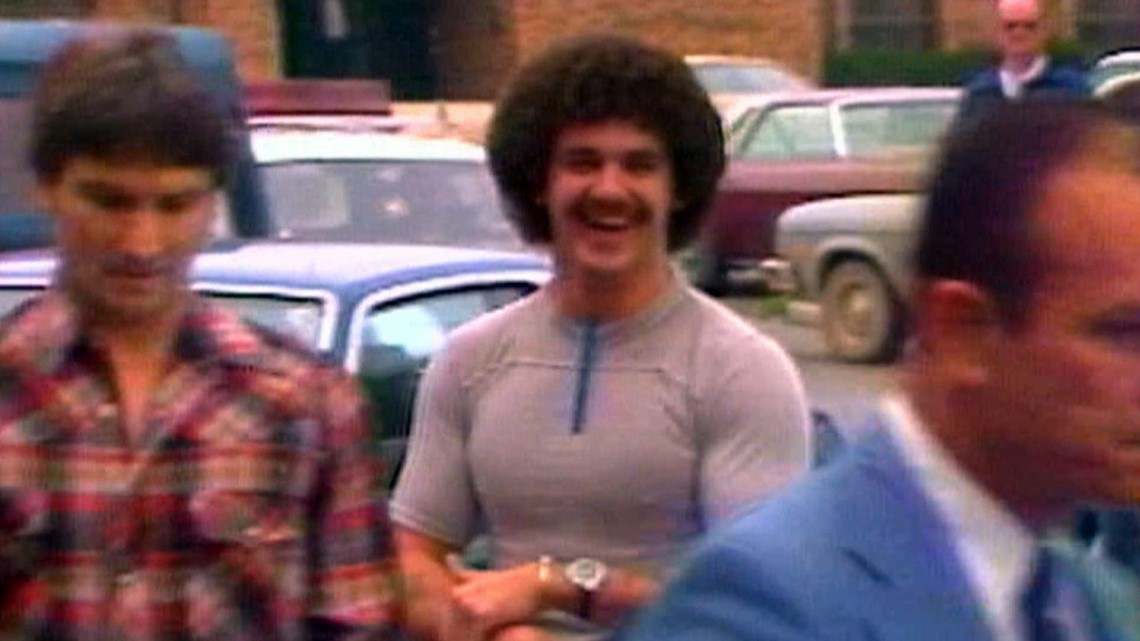

Gibson was reasonable to think he would die at Brushy. He arrived in the late 1970s with a 99-year prison sentence. As a 17-year-old, he was arrested for armed robbery. While he was in the Knox County Jail for robbery, he beat a fellow inmate to death. Gibson was convicted of second degree murder and sent to Brushy Mountain State Prison.

"When you're 18-years-old and come here, you have no hope. This is your life," said Gibson. "This was the most violent place in Tennessee. I've seen many men stabbed and beat to death right here in this breezeway, because they would get trapped in here with somebody on each end where they couldn't get out. You're in prison. But wherever you are, you can't get away. If you're a snitch and run your mouth, eventually somebody is going to get to you."

Gibson's childhood was spent bouncing around in group homes. When he came to Brushy, he was illiterate. But he read the situation in Brushy to mean he could either be predator or prey. He became one of the most feared inmates in the prison.

"I was wicked. I had a wicked heart, wicked mind, and wicked thoughts. You see those steel vents back there? We would take those steel vents off and make homemade knives out of them. We could get everything into this prison from hacksaw blades, drugs, bullets, and anything else you can imagine," said Gibson.

Gibson can be seen in footage from a 1978 WBIR series investigating violence at Brushy Mountain Prison. Warden Stonney Lane gave WBIR unprecedented access for a brutally honest look at life at the prison. Lane was completely transparent about the problems the prison deals with, including problems with drugs, rape, and the many ways inmates take advantage of each other. Lane also allowed inmates to speak freely to WBIR about the environment in the prison.

"This institution right here is the worst place on Earth. They are perpetrating murders up in here and the only victims are black people," said one unidentified black inmate.

When Gibson watched the archive footage, one of his first comments was about the "dangerous guys" in the story. He listened and agreed with Warden Lane's comments about three inmates killed at the prison.

"That's certainly three too many. But in the type of atmosphere and confinement you have here, it's not surprising," said Lane.

"Stonney Lane was one of the best wardens that ever came into Brushy Mountain. He was the warden and did his job, but he treated men like men," said Gibson.

Lane's mutual respect for inmates made him extremely popular. Some inmates gave him a going-away party when he left Brushy Mountain to become warden of the Morgan County regional prison.

His replacement, Herman C. Davis, was considered hardline and unforgiving. Gibson says the approach added sparks to what was already an explosive environment.

"Nobody had respect for Herman C. Looking back on it now, I don't have any hatred or ill will. He was just doing what he thought was right. But he did not treat prisoners with respect and he didn't get any respect," said Gibson. "It absolutely had an effect on the environment here."

Gibson said individual feuds between inmates escalated for a few years. There were attacks, retaliation, and eventually two groups were bound to kill each other. The two groups were black and white, but Gibson says they were not a gang and the violence was not racially-motivated.

The prison tried to diffuse the situation by separating the two groups. Gibson said the black inmates in the feud were sent to West Tennessee. Then, they were brought back to Brushy Mountain.

"The same administration that separated us signed off on bringing them back. Not only did they bring them back, they put them right in the same unit with us. So, there we are. You've got a choice because you know somebody is going to get killed," said Gibson.

Gibson and the other inmates began cutting the bars of their cells with hacksaw blades. They hid the cuts by filling the cracks with soap and then painting the bars.

Gibson won't say exactly who or how, but someone smuggled a .25 caliber handgun inside the prison to someone in his group. Reports at the time said a guard resigned after he failed a lie detector test about the smuggled gun.

"Just like you've got some crooked cops on the outside, you've got crooked guards inside the prison. And money would talk on the outside and talk on the inside. Guards and inmates knew who could be trusted and both sides would be protected by the situation," said Gibson.

In February 1982, Gibson and six others made their move. The first step was to take the guards hostage.

"We had someone down the hall act like they were sick so the guard would go down there. You bend the bars and jump out with a knife and they're trapped," said Gibson.

The guards were held captive with knives while the group took their keys. They then went to the rival inmates' cells and opened fire. The black inmates looked up to see their enemies outside their cells with a loaded gun.

Gibson's group shot and killed two men. They then shot two others who survived by backing into the corner and covering themselves with a mattress.

"He came up with a cotton mattress and it was thick enough to stop a .25. That's the only reason he lived. Now, I thank God he did," said Gibson.

Gibson said the group also had a secondary target.

"If Herman C. Davis, the warden at that time, had come in, we were going to shoot him. But he didn't. I thank God he didn't," said Gibson.

When the shooting was done, the guards were set free and the group surrendered without resistance.

Gibson will not divulge who pulled the trigger, be it him or another member of the group. He still clings to a prison code of confidence. As he put it, "If there is something you don't want told, don't tell it." Besides, Gibson says the entire group was in on the plan and equally guilty.

After the shooting, the guards and warden began taking public shots at each other. Some guards said the warden knew or should have known there would be violence. Other guards came out in support of the warden. Davis claimed ignorance and blamed the guards.

"They didn't tell me. If the officers knew, they should have done something about it," said Davis during a February 1982 interview.

While Warden Davis and the guards were involved in their own power struggle, Gibson's group arraigned for two counts of murder, two attempted murders, and four kidnappings. The group's bold actions earned them a nickname: the magnificent seven.

"I don't remember who came up with it or started calling us that, but it stuck because of the old western film," said Gibson. "I don't say any of this stuff boastfully. I'm just telling you what happened. They called us the magnificent seven."

WBIR footage of the group's arraignment shows they were clearly not bothered by the crimes committed. The seven inmates laughed and seemed to relish the attention of news crews. Gibson jokes and laughs with reporters as they walk in the courthouse.

"That was me. I was a jokester. I had a foolish heart and had a wicked heart," said Gibson. "That's why I say I deserved every single day I spent in prison."

The shooting tacked on decades to Gibson's previous sentence. He spent the next four years in solitary confinement.

"That's 23 hours in a cage and then they'd take you out in a little doggy-run to exercise. People in prison were saying there's no hope for Robert Gibson. And looking back on my life, there was no hope. Other than Jesus Christ. I didn't know it at the time," said Gibson.

Gibson credits the change in his life to visitors such as Donnie Moore, who expressed care for his well-being.

"For eight years, Donnie would visit and talk to me and accepted me for who I was. He knew a man named Jesus Christ. He said I know there is hope for you. He never shoved religion down my throat. He would just tell me, 'I love you, boy. I am praying for you.' It took eight years, but I finally realized who I was. I was a sinner who needed a savior. My heart was wicked," said Gibson. "January 5, 1988, that Holy Ghost got ahold of my heart. I was born again. Not to get out of prison, but because I was a sinner."

After more than a decade of behavior that made him one of the devils at Brushy Mountain, many people at the prison were skeptical of his newfound desire to behave like an angel.

"No, they didn't trust me overnight. They kept saying, 'Hold on. You'll see.' But I really had changed. I still had some bumps in the road and was not perfect, but kept trying to do the right thing," said Gibson.

Gibson learned to read by reading the Bible. He learned the words so well, he can rapid-fire quote chapter and verse. He says that is not what makes him a Christian.

"There is such a thing as jailhouse religion. People act like they've found God to try to get out. The same thing goes for church-religion on the outside. There are people who go to church and pretend to be holy when they're not. It has to be in your heart," said Gibson.

And after a several years as a model inmate who ministered to others and tried to guide them to do the right thing, everyone at Brushy Mountain knew Gibson's turnaround was genuine and sincere. In 1999, he was released from Brushy Mountain State Prison.

After a year, a verbal altercation with his now ex-wife constituted a violation of his parole. Gibson was back in prison.

"I raised my voice and yelled at her. I called her a liar. They said that was considered a threat, which was a violation. When I was back in prison, it was as low as I've ever been to know I put myself back in this situation. But I just kept working and trying to work for God."

After another decade, Gibson was again released in 2011. He completed his probation and parole. He no longer owes the state any time or obligations for his crimes.

Gibson says he does owe Jesus for the opportunity to live freely in the outside world.

"I do not deserve to be standing right here today, free in society with no more time, to share with you today these stories. And the only reason I'm here today is because of Jesus. It's good. God is good," said a tearful Gibson.

Gibson now lives in Knoxville and makes a living by removing trees. He still visits and ministers to inmates. Many churches have invited him as a guest preacher.

Gibson speaks to people as someone who truly changed his life at Brushy Mountain Prison from a violent predator to a man who prays.

"Right here at Brushy Mountain, this place has a history of all types of violence that you can possibly imagine. I've seen that and experienced that and don't want no more of it. I've done my time and try to give society back something positive from when I was negative," said Gibson.

Final Days and Future

From beginning to end, Brushy Mountain Prison followed a path of labor and money. It was built to extract coal for profit. It also provided an economic engine and good jobs for people in Morgan County.

"Brushy Mountain Prison has been one of those staples of Morgan County," said Don Edwards, Executive of Morgan County. "Generations of families made a living at this prison."

The guards at Brushy Mountain were in a unique position in Tennessee. They were the only guards that were part of a union. They could publicly fight for better benefits and staffing while criticizing management without unreasonable fear of retribution.

A strike by guards in 1972 escalated to become a stalemate that shut down the prison for almost four years. When Brushy reopened in 1975 into 1976, it remained a prison where guards said there were too many inmates and not enough staff.

Understaffing was blamed for several notorious incidents at the prison. When James Earl Ray escaped in 1977, the guard tower closest to the escape point was unmanned. In 1981 when Ray was attacked in the prison library, guards said the incident was the result of inadequate staffing to monitor the inmates.

In 1983, the guards went on strike for 12 hours before voting to return to work. This came after six guards were injured during scuffles with a large inmate. The guards said their batons and other gear to break up fights had been replaced with ineffective plastic and fiberglass products that would not subdue prisoners.

"I wish that Tennessee had better. But we don't have them and we have to work with what we have," said a Department of Corrections official to the guards.

Job cuts continued through the 1990s. In 1997, layoffs across the state were announced. The job of warden at Brushy Mountain State Prison was also consolidated to also oversee the Morgan County Regional Correctional Facility.

As consolidation continued with plans for some larger regional prisons, Morgan County leaders battled to save jobs and attract the new expansions. In 2001, the state announced it would expand the regional prison in Morgan County to become the sprawling Morgan County Correctional Complex. The expansion increased capacity to 2,400 inmates and brought 400 new jobs to the county. Estimates at the time said the new prison could bring a $90 million economic boost to the county.

"We had to fight for it," said Alma Jones, county executive in 2001. "We thank Phil Bredesen for thinking of the poverty-counties. We needed this."

Consolidation and expansion of regional prisons also brought the end of Brushy Mountain State Prison. The outdated building's small capacity of a few hundred inmates combined with expensive operating costs led to its closure in 2009.

This historic prison sat empty for years. In 2013, voters in Morgan County approved a referendum that allowed the county's economic development board acquire the old prison from the state. The board, in turn, has leased the site to entrepreneurs with the Brushy Mountain Group who are working to turn the site into a distillery and tourist attraction.

"Morgan County needs economic development. We need jobs. And people are very excited about the prospects of that economic development taking place right here at Brushy Mountain," said Edwards. "The historical site itself is going to be preserved. And that is important to almost all Morgan Countians."

As of this writing, developer Brian May with the Brushy Mountain Group says the distillery is just a few weeks from opening to the public.

"We've been in the banging nails phase for so long, even more exciting because the general public gets to see what we've been experiencing for five years. We're really close to the finish line. The moonshine still house is ready to turn on and we'll be making nine different flavors. The prison is being cleaned up and made safe so we can do tours. We'll do an RV park, some primitive camping, a local farmers market, a museum, a gift shop, and restaurant," said May.

May also hopes to fill the stone-walled prison yard with music.

"We want to do a regular monthly concert series. At least one or two huge concerts and maybe even some weekend music festivals. To be able to see some of these cool bands in what could be one of the most beautiful settings in the entire state, that just happens to be at an old prison where we're going to make moonshine, is kind of cool," said May. "We want to have something here the locals can be proud of. And we believe they will be proud once they see it and we're open."

Now the site has gone from a place where people paid for their crimes with hard time to a place where free people will pay for hard liquor and history.

"When you stand on these grounds, you do feel it. The history and the people that came through this place and ran this place, you get to experience some of that," said May.

Reporter's note: Below are short SideBar (pun intended) videos about Brushy Mountain Prison's history. If the videos do not display in the article, click the link below the embedded player to go directly to the video.

SideBar 1 - Movies, Music, and Books

[ Video: SideBar 1 - Movies, Music, Books ]

Brushy Mountain State Prison's cultural influence is visible in films, music, and literature.

The novel and film The Firm features a fictional inmate at Brushy. In The Silence of the Lambs, the cannibalistic character Hannibal Lecter escapes while being transferred to "Brushy Mountain State Prison, Tennessee."

Musicians performed concerts for inmates at Brushy, including a 2001 concert by country singer Mark Collie featuring Tim McGraw.

Brushy Mountain is also the topic of many tunes. The song "Don't Come Out of the Hole" by bluegrass band Blue Highway is about an inmate who will be shot if he tries to leave the coal mines at Brushy Mountain.

In 2014, Old Crow Medicine Show released the song "Brushy Mountain Conjugal Trailer" on the band's Grammy-winning album Remedy. Although the song is entertaining, the truth is no conjugal visits were ever allowed at Brushy Mountain.

SideBar 2 - Geronimo the Deer

[ Video: SideBar 2 - Geronimo the pet deer ]

In the early 1970s, a young deer fell off the cliff and landed behind the walls of the main yard at Brushy Mountain State Prison. The inmates named the free-falling fawn "Geronimo" and kept it as the prison's only pet. The deer was tamed and liked to chew unlit cigarettes.

When a labor dispute forced the prison to shut down from 1972 through 1975, the inmates were moved to Nashville. Geronimo was left behind to roam the corridors of Brushy Mountain with its future undecided. Some lawmakers from Knoxville proposed moving the animal to the zoo. The inmates voted on Geronimo's fate. 127 voted to move the deer to the prison with them in Nashville, 12 voted to relocate Geronimo to the zoo, and one inmate voted to slaughter Geronimo and serve it as a venison prison dinner.

The state paid to move the deer to Nashville with its friends. Geronimo had trouble adjusting to life away from Brushy Mountain. The Nashville warden said the deer threw "temper tantrums." One inmate's face was nicked by the deer and required stitches. When the prisoner was taken to the hospital for medical attention, he briefly escaped.

Geronimo's days behind bars ended when the animal broke its leg. Veterinarians had to amputate the limb. Newspaper reports do not specify where the deer spent the rest of its life, but it still lives in the hearts of inmates and guards who cared for it in the 1970s.

SideBar 3 - Talents and Recreation

[ Video: SideBar 3 - Inmate talents and recreation ]

The prison housed the "worst of the worst" criminals. Beyond criminal activity, the inmates had many artistic, musical, and athletic talents they put to use while behind bars. The cafeteria is covered with beautiful murals painted by an inmate. The artifacts kept in storage include incredibly detailed jewelry, including a ring shaped and carved from a bent cafeteria spoon.

Musically talented inmates formed the Brushy Mountain String Band in the late 1940s and played at benefit concerts. A 1949 concert advertisement in the Knoxville News Sentinel touts a show at the Central High School Auditorium as the "greatest, most unusual entertainment ever presented" comprised of "16 men from Petros prison."

The prison also featured a baseball team that frequently played outside squads when baseball was a popular recreational sport through the 1960s. The baseball team sometimes ventured away from the prison and played at Caswell Park in Knoxville.

The Brushy Montain softball team also competed against any outside teams willing to play a game within the prison's walls.

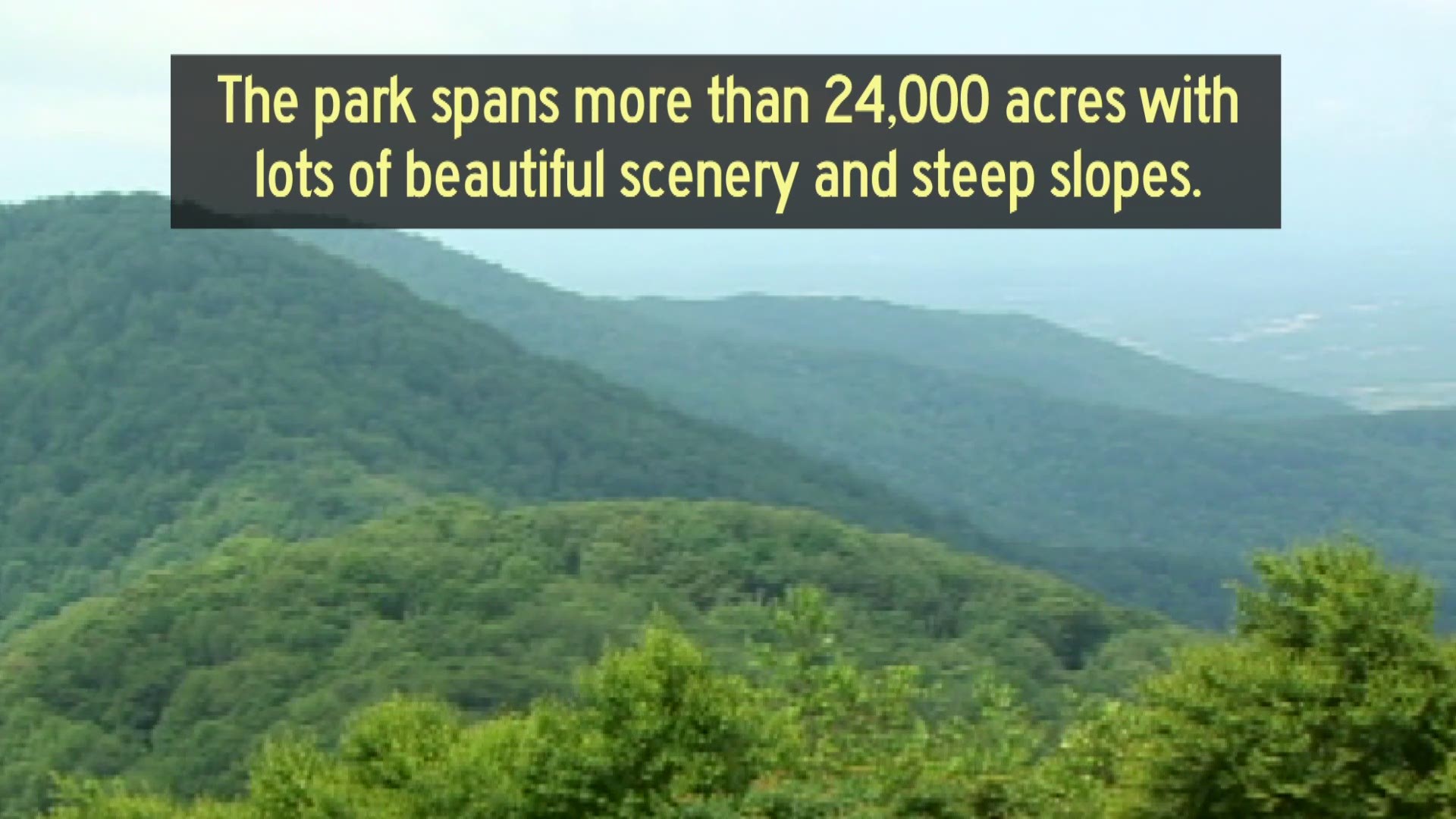

SideBar 4 - Frozen Head and Barkley Marathons

Much of the land originally purchased for Brushy Mountain Prison convicts to mine coal is now the Frozen Head State Park and Natural Area. The park features more than 24,000 acres of scenery and steep hills. Frozen Head State Park is also the site of the Barkley Marathons. The race is considered by many to be the world's toughest ultra-marathon. Runners have to complete the 100-130 mile unmarked course within 60 hours. From 1986 to 2018, only 15 runners have successfully completed the Barkley within the time limit.

SideBar 5 - Helping Hounds and Hands

[ Video: SideBar 5 - Helping Hounds and Hands ]

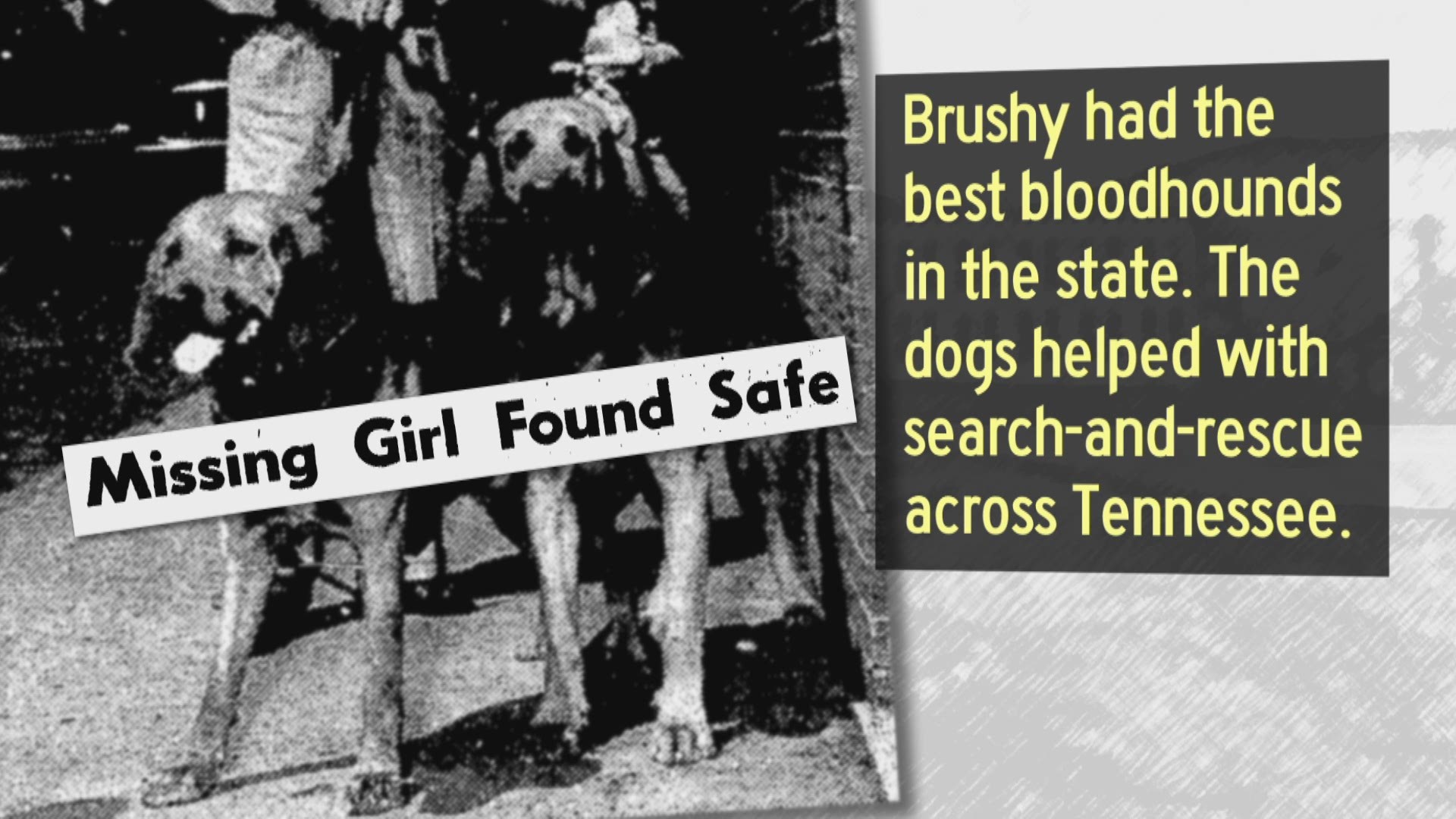

Another sidebar in Brushy Mountain's history pertains to the many ways its inmates and guards made a positive impact one people outside the prison. Brushy had the best bloodhounds in the state for tracking escapees, but they also helped with search-and-rescue efforts across the state. When coal was a method of heating homes, the prison donated coal from its mines to the needy during harsh winters. When winter storms downed trees, teams of inmates from Brushy cleared roads and utility poles in the tough terrain. In the 1940s, inmates at Brushy pooled their meager prison pay to buy defense bonds and help the war effort because they wanted to "do our part."

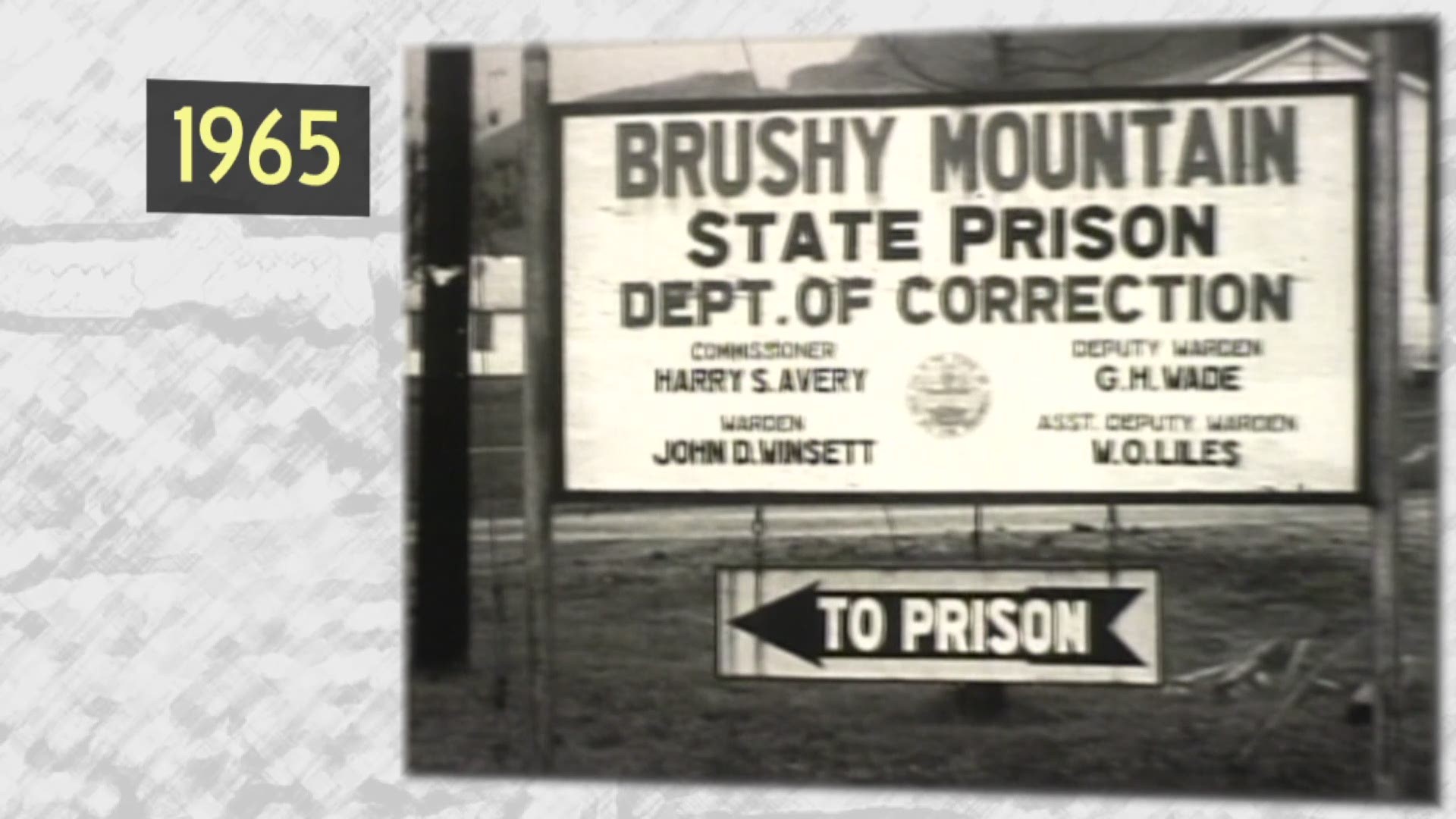

SideBar 6 - Brushy Mountain Entrance Signs

[ Video: SideBar 6 - Entrance Signs ]

Don't be fooled by the antique appearance of the stone entrance sign at Brushy Mountain Prison. It was constructed in 1996 for the prison's centennial. WBIR archive footage shows a few of the many faces at the entrance that greeted visitors to the prison.