At exactly 9:51 a.m., the Delta Airlines flight touched the ground. It was carrying the remains of the late WWII fighter pilot Harold DeMoss, which was draped in an American flag and ushered off the tarmac into a waiting hearse by six Navy personnel wearing their dress whites.

It has been more than 70 years since the 21-year-old Navy ensign — who left Nashville to join the Navy as a teen, never to return — crashed his plane in a remote outcrop on the Hawaiian island of Oahu.

And it has been exactly that long that three generations of DeMoss' family have been engaged in a lengthy, frustrating but ultimately determined battle with the Pentagon to get DeMoss home, where a plot in the family's 100-year-old cemetery has been set aside for him since his death on July 23, 1945.

Yet for all those years, DeMoss's remains have lain where his plane went down on American soil — just 40 miles from the offices of the Pentagon agency charged with retrieving the remains of all fallen soldiers.

The failures of the agency — now called Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency — to bring home some 83,000 fallen soldiers from wars past has devastated thousands of families and drawn withering criticism from Congress. Its scandals have included staff members who spent money on "military tourism" trips to Europe, staying in luxury hotels and enjoying lavish meals. Three years ago, the agency was reorganized. A report made public last year found it was still plagued with problems.

As DeMoss' casket was carried across the tarmac, his younger brother, Jim — now 85 — stood with his hand over his heart.

"He finally made it," Jim DeMoss said quietly.

DeMoss' funeral on Saturday was marked by a statewide "day of mourning and remembrance" for DeMoss in a proclamation issued by Gov. Bill Haslam. The governor ordered all flags flown at half staff.

"You cannot ignore the fact that after waiting 73 years this family has sacrificed much," said Many-Bears Grinder, Commissioner for the Tennessee Department of Veterans Services, speaking at DeMoss' funeral at the family cemetery in west Nashville, not far from where the DeMoss brothers grew up riding horses on their family farm.

TSA staff remove the remains of Harold DeMoss, a pilot shot down during WWII off the plane, from the cargo department of Delta flight #1066, at the Nashville International Airport in Nashville, Tenn., Wednesday, Sept. 12, 2018. (Photo: Lacy Atkins / The Tennessean)

The long wait for the fallen

Today more than 72,000 Americans who served in WWII still remain unaccounted for, including more than 1,200 from Tennessee.

Harold DeMoss crashed his plane during a night flight training on July 23, 1945 at shortly after 1 a.m. on a craggy outcrop on the island of Oahu.

A search party reached the site three days later, burying what they could find. Weeks later, another group returned and a Navy lieutenant recited the "Lord's Prayer" over the shallow grave next to the remnants of F6F-3 fighter plane.

In the midst of the war — it was just weeks away from the Japanese surrender - DeMoss' parents were told they would have to wait to get their son back home.

In 1949, his parents received a Navy memo declaring the remains unrecoverable. By then, the site was overgrown, they were told.

In 1968, his mother received a politely worded rejection letter to her request for a military escort to try to reach the site.

"It would be sad but I'd like to see/The grave where dear Harold lies/And cover it with flowers/Beneath the Hawaiian skies," she wrote in a poem.

His parents still held out hope that the military would recover his remains. In the family cemetery, Harold's plot covered with grass and clover under the shade of two red cedar trees, has lain waiting for him for 70 years.

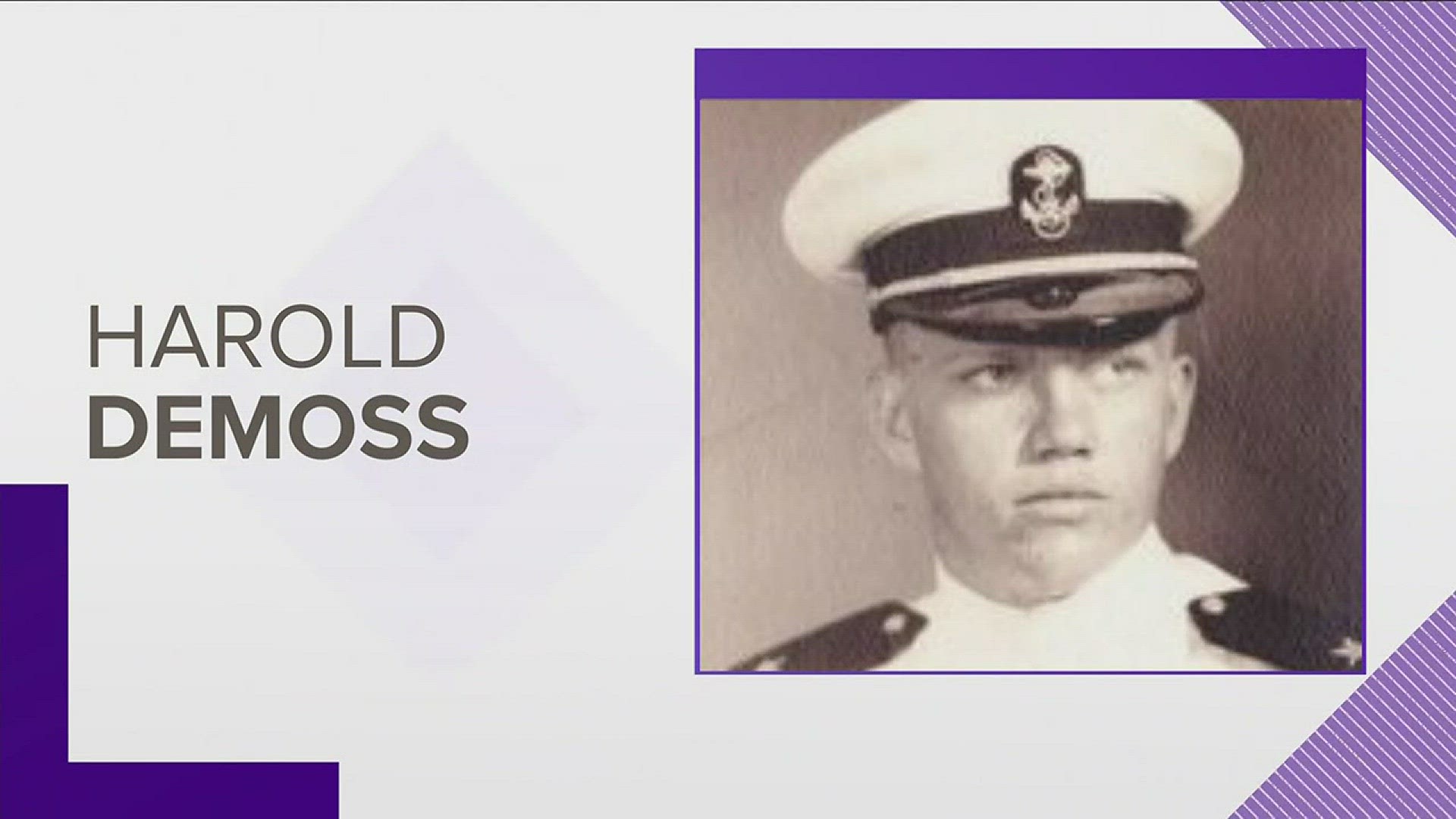

Harold DeMoss was just 19 when he enlisted in the Navy. Harold loved to fly, his brother, Jim DeMoss, said. Harold DeMoss, a David Lipscomb High School graduate, was just 19 when he enlisted in the Navy. “Harold loved to fly,” his brother, Jim DeMoss, said. (Photo: Submitted)

His mother died in 1997, five years after the death of her husband. "She never did get over it," Jim DeMoss said.

After their death, it fell to Jim DeMoss' grown daughter, Judy Ivey, to try to get the Pentagon to retrieve DeMoss.

By 2011, Ivey was frustrated by the slow response from her repeated calls, emails and letters to Department of Defense officials and congressional representatives.

"One office offered to get us a flag," she said. "I remember thinking we don't want the friggin' flag. That's not what we were after."

Ivey then did what many families trying to get their loved ones returned by the military.

She contacted volunteers.

The Hawaii Aviation Preservation Society agreed to send out search parties. They examined all of the accident reports carefully kept by Demoss' mother for most of her life and pinpointed a likely search area.

It took nine tries but the volunteers reached the remote site a few months later. Some seven miles away from the nearest road, covered in thick vegetation and overrun by wild pigs, they stumbled upon a plane tire and scraps of metal.

The volunteers sent the exact coordinates of the site to military officials.

It would take another eight years for the $130 million agency to finally get the remains home to Nashville that volunteers found in a few short weeks.

Jim DeMoss is surrounded by family at the funeral of Harold DeMoss, a pilot who was shot down during WWII, at the DeMoss Family Cemetery in Nashville, Tenn., Saturday, Sept. 15, 2018. (Photo: Lacy Atkins / The Tennessean)

In 2015, a USA Today Network - Tennessee investigation detailed the delays and often contradictory information given to Ivey as she persisted. Military press picked up the story. Congressman Jim Cooper's office intervened.

Faced with such public scrutiny the agency set a date for retrieving the remains from the crash site.

A team of Navy Seals were lowered by helicopters to excavate the site in 2017. A forensic examination would take months longer. Then on May 11, Ivey got the call. The DNA wasn't conclusive but they found DeMoss's wedding band, a fragment of an identity bracelet he wore and his Navy wings.

The family declined the military's offer for a burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

Instead, on Saturday the coffin containing Demoss' remains was slowly lowered into the ground beside the graves of his mother and father in a cemetery filled with the tombstones of generations of DeMoss who have served the nation since the Civil War.

Jim DeMoss remained largely silent through the brief service, where he was presented with a state flag, the flag draping his brother's coffin, a small velvet bag containing the shell-casings from a 21-gun salute, and the slow and mournful version of Taps played on the trumpet by a Navy man in dress whites.

He remained seated as the Navy personnel left the cemetery and two men worked to fill the grave with dark red dirt and cover it over with sod.

The headstone won't arrive for four or five months.

"It don't much matter," DeMoss said as he prepared to leave. "I know where he is now."

Reach Anita Wadhwani at awadhwani@tennessean.com; 615-259-8092 or on Twitter @AnitaWadhwani.