KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — You may have heard health experts speak of the COVID-19 pandemic as something unprecedented since the "Spanish flu" of 1918. But how much can our technology-dominated society relate to what people endured more than a century ago?

A lot. A whole lot. In fact, it's remarkable how similar the situation was in 1918 when looking through the archives of East Tennessee newspapers.

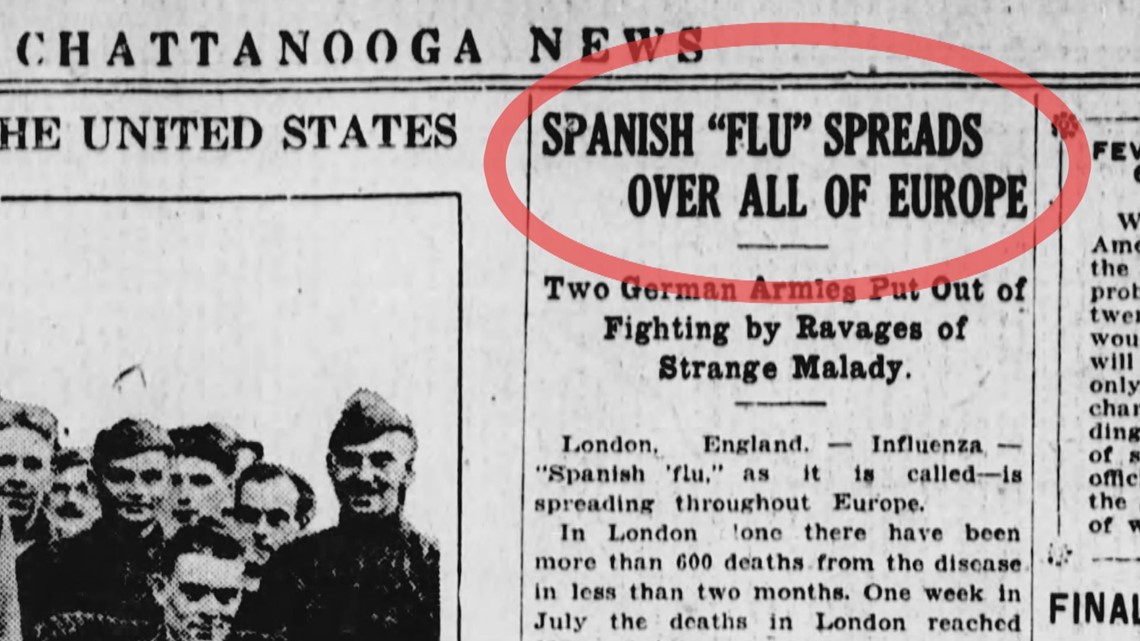

The world was at war in the summer of 1918 when the "Spanish flu" started spreading across Europe. Local headlines in August noted the virus was hurting Germany's military efforts.

As American troops came home through a handful of seaports, they caught the flu and brought it home to every corner of the country. The assistant secretary of the Navy fell ill on a ship and recovered. His name was Franklin D. Roosevelt, the future president of the United States.

Newspaper articles in September 1918 note the flu was especially intense in New York City and New Orleans.

The flu showed up in Nashville and Johnson City in early-September. However, it was downplayed as mostly mild with no need for panic or hysteria.

By the end of September, Spanish flu spread across the entire state. Doctors warned people to stay home if they were sick.

State health leaders urged people to stop hugging and kissing each other. That was undoubtedly a difficult pill to swallow for affectionate grandmothers greeting adorable children.

Grocery stores started limiting hours and deliveries. Public gatherings were discouraged by the government and deemed taboo.

On October 5, 1918, the City of Knoxville had 200 confirmed cases of Spanish flu, not counting the students at the University of Tennessee or troops at an Army hospital set up at Chilhowee Park.

On October 10, the number of cases in Knoxville was 1,045. By October 14, it was 2,401.

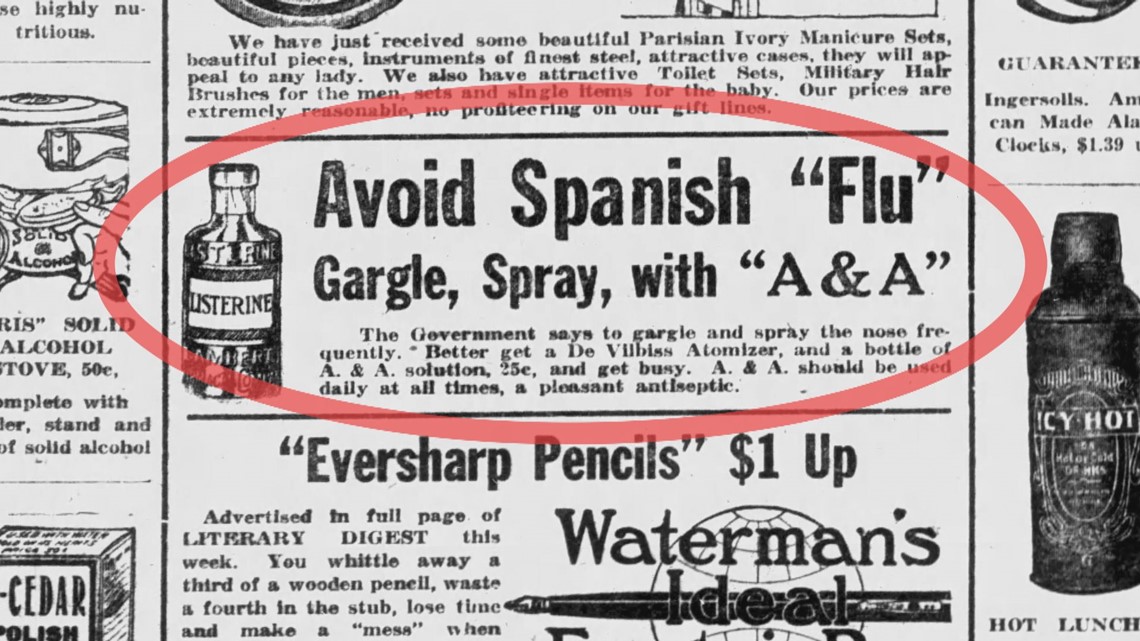

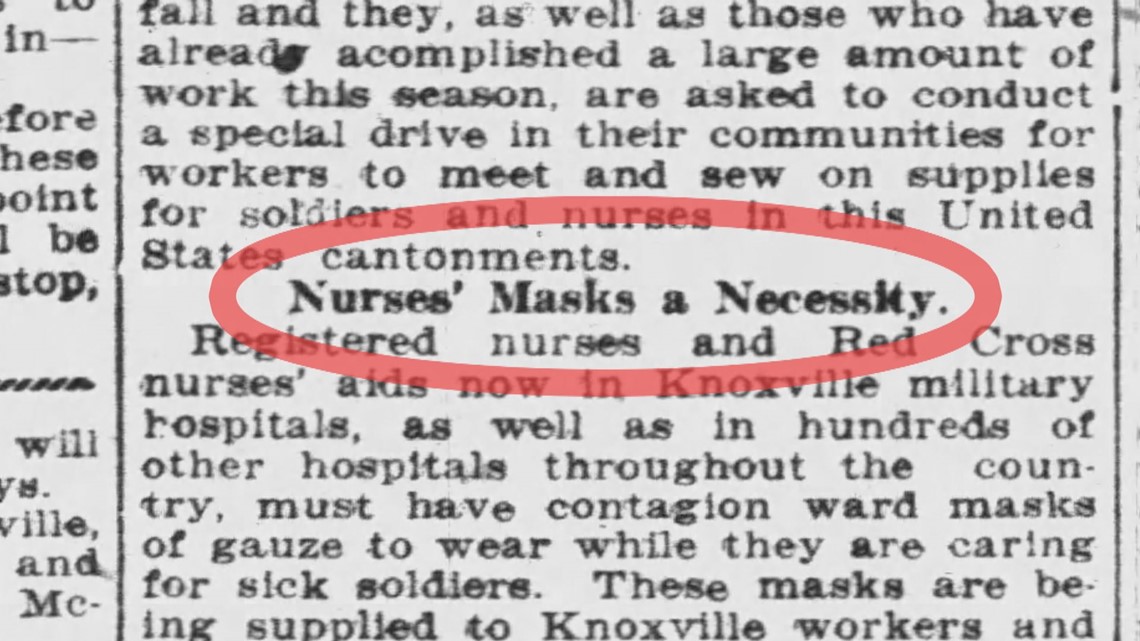

People were told to take steps to ward off influenza by not congregating, covering your mouth and nostrils with a handkerchief or mask, and "keep your mouth shut and your hands clean." There were other bits of advice that seem out of place today, such as taking laxatives and gargling with antiseptic.

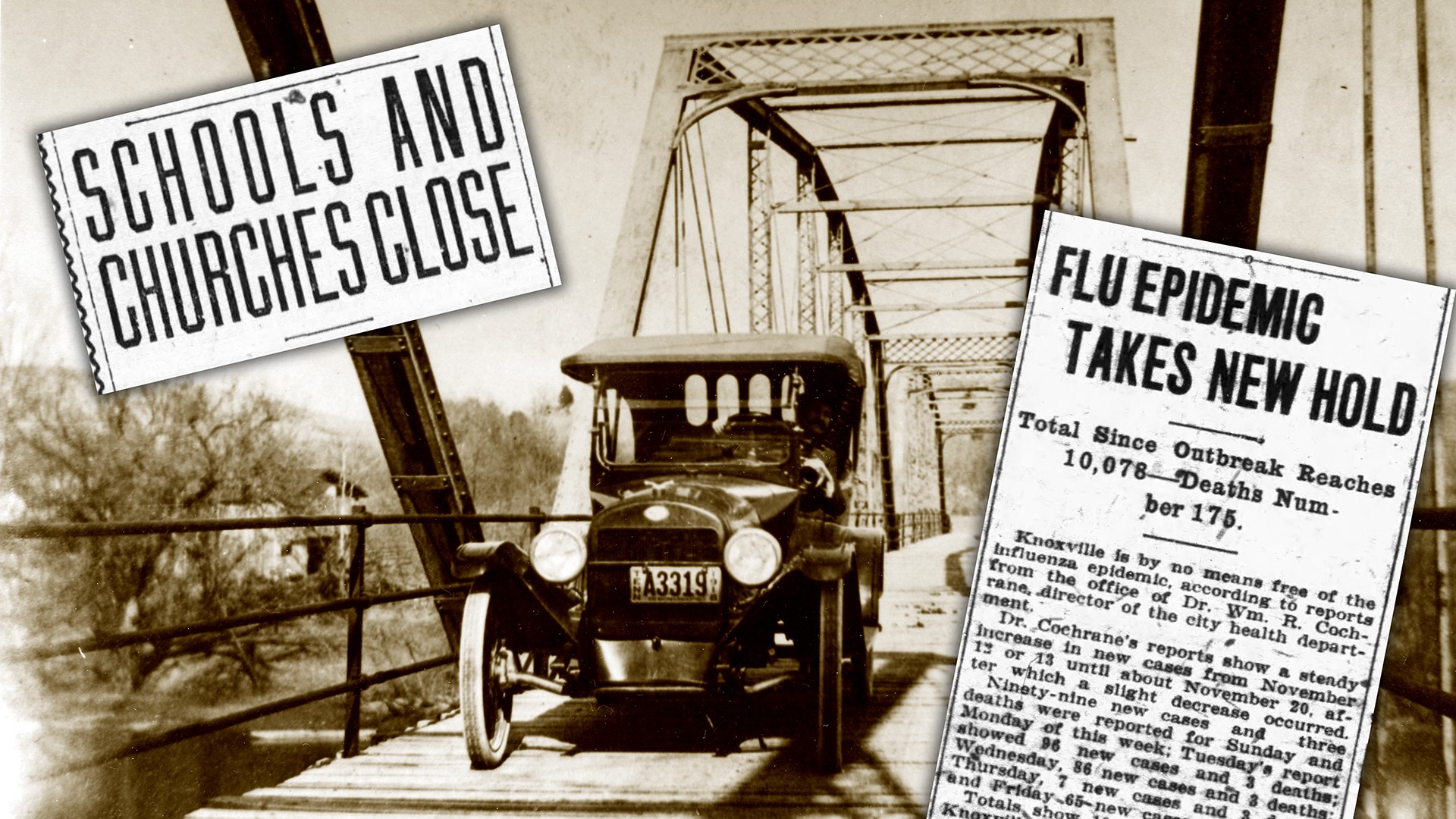

In early October, theaters closed. Public schools closed. The University of Tennessee canceled classes October 9.

No school. No church. No funerals. The Red Cross reported a shortage of masks for nurses.

The flu hampered telephone operators and postal workers in East Tennessee. Fatigued physicians were unable to answer some calls.

The outbreak wasn't just in bigger cities. The virus rocked mining communities such as Oakdale and Coalfield. Newport and Greenback were hit hard by the flu.

As businesses were hurting, some people saw the opportunity to capitalize on the situation. There was a lemon shortage as it was thought the citrus aided flu-stricken people. Some lemon speculators bought and hoarded the fruit to boost the price.

A shoe store on Gay Street advertised drafty environments and slippers might give you the flu. "Get shoes today and be ready. Get 'em at Spence Shoe Co."

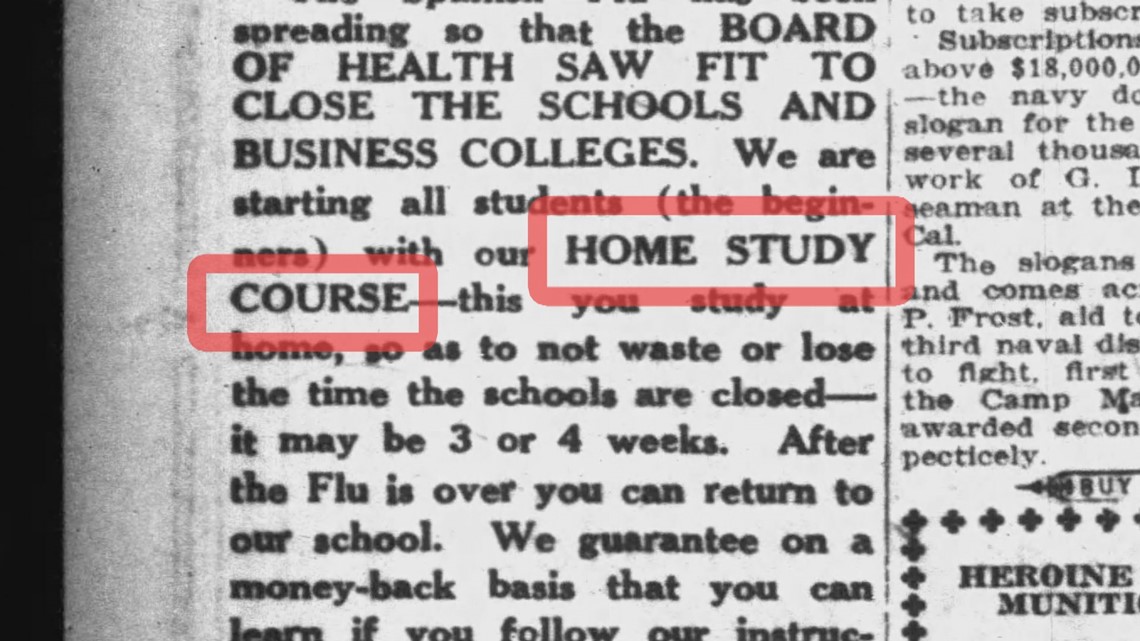

Ads in newspapers targeted parents by offering educational courses their children could study at home until schools reopened.

With people quarantined and theaters closed, libraries experienced a big boost in checked out books.

By October 24, Knoxville reported 6,932 cases and 91 deaths. The situation was said to be improving because only 226 new cases and nine deaths were reported that day.

On Friday, Nov. 1, 1918, the city of Knoxville announced the flu ban would end on Sunday. Churches would be allowed to reopen. At that point, there were 131 deaths and 8,984 cases in Knoxville since the epidemic began.

There was spike in cases when Knoxville resumed business as usual. The headline on Nov. 23, 1918 in The Journal and Tribute read, "Flu Epidemic Takes New Hold." The total cases since the outbreak climbed to 10,076 with 175 deaths. Nonetheless, Knoxville was not hit as severely as other parts of the state and nation.

The spike in Knoxville cases in November also coincided with a large victory celebration on Gay Street when the war ended. Armistice Day was Nov. 11, 1917.

As the population celebrated the end of what was then the deadliest war in the history of the world, the Spanish flu virus had killed an estimated 20 to 40 million people worldwide. That's two to four time the number of people killed in the First World War. Headlines noted, "Spanish Flu Worse Than Hun Bullets." The virus killed more than half a million Americans.

The death toll from the Spanish Flu was the worst since the bubonic plague killed an estimated 62 million Europeans in the 1340s.