KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — This Black History Month, we're honoring African-American leaders in our community. Folks who helped make Knoxville a better place for everyone, regardless of the color of your skin.

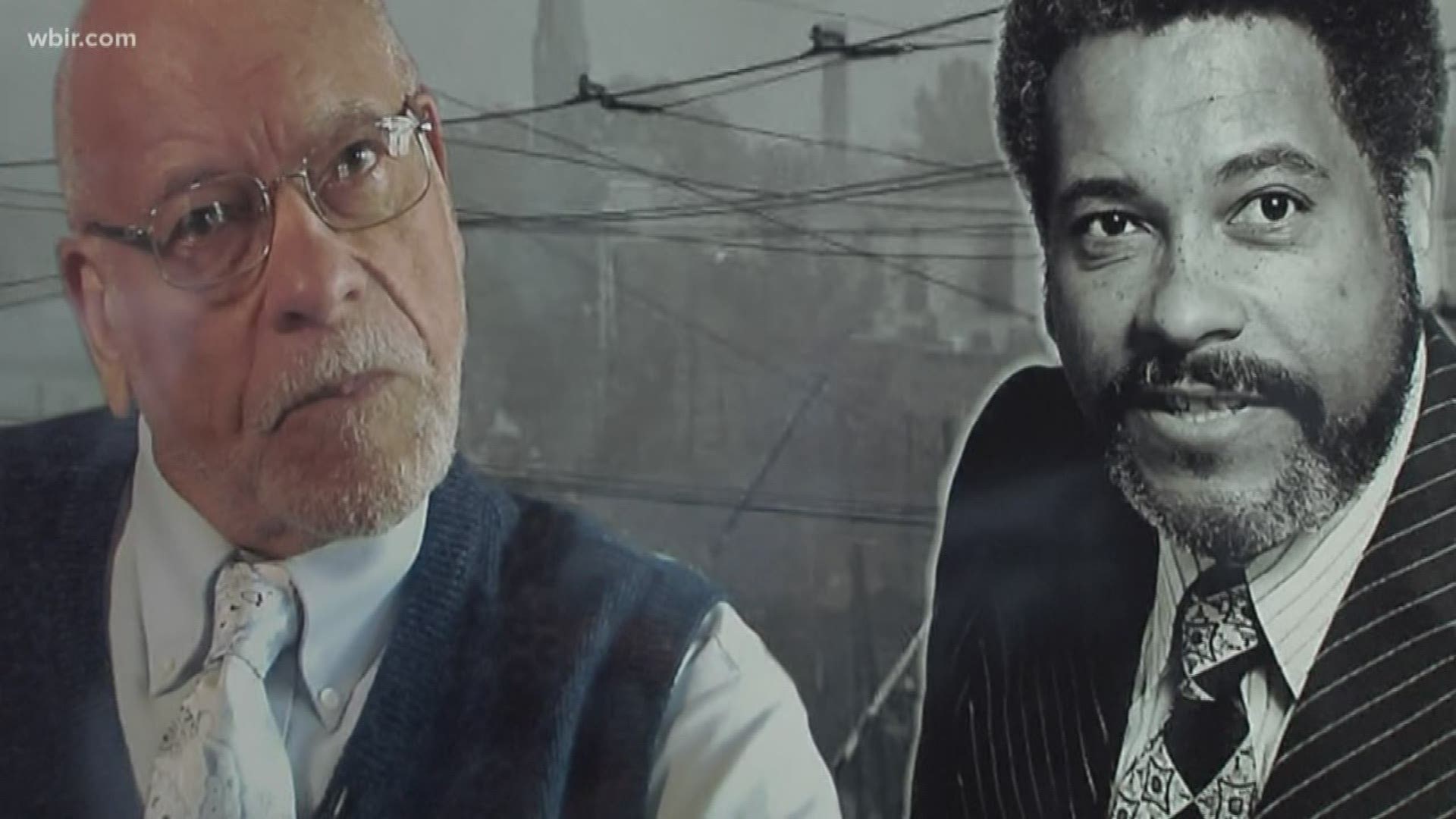

Robert "Bob" Booker was born in ‘The Bottom.’ That was the nickname for the poorest, black community in East Knoxville back in the 1930s.

“My mother was a maid, sometimes a cook,” said Booker. “My father, although he wasn’t around, he worked at an auto parts place on Jackson Avenue.”

Growing up in the segregated south, Booker saw small glimpses of how awful segregation really was while he was a student in grade school.

“Our teachers protected us from segregation as much as they could,” said Booker. “They would change the words in certain songs and host our own spelling bee because we couldn’t participate in the Appalachian Spelling Bee.”

At the time, Booker didn’t really know what career path he would take. But his teachers encouraged him to write.

“I started writing poems in the 4th and 5th grade,” Booker said. “I would write rhymes, and I would also write about nature. I remember a poem I wrote about a bird that could fly anywhere and be free.”

In-spite-of racism, segregation, and poverty, Booker would grow up to become a champion for change.

At 17-years-old, Booker started "The Page," a student-run newspaper at Austin High School. He also gave his first public speech at a school board meeting where he called out inequalities in the local school system.

"I've a been a happy go lucky kid," said Booker. "But I've always been concerned with inequality."

One year after graduating from Austin High School, Booker served in the U.S. Army. That’s when he finally got a taste of the freedom he wrote about as a child.

“I spent almost three years in France and in England. For the first time in my life I was free. I could eat in any restaurant, stay in any hotel, go see any movie or any play, anywhere I wanted to go!” said Booker. “For three years, free!”

After three years of service, Booker returned to the U.S. and enrolled as a student in Knoxville College.

“I came back to Knoxville May of 1957, and I'm back to square one. Nothing had changed in race relations,” said Booker. “After having been free for three years, my conscience was awakened. And I said, ‘We have to do something about this.’ What it was I didn't know, until the Greensboro students showed me what we ought to be doing.”

After a month of peaceful protests, downtown lunch counters were desegregated.