In life, Jerry Leon Johns liked to boast that he'd never hurt a woman and no one could ever prove otherwise.

In death, his crimes may finally be catching up with him.

The Tennessee Bureau of Investigation announced in December that a grand jury had determined the Rockford, Ill., man likely killed a woman found strangled and bound Jan. 1, 1985, along Interstate 75 in Campbell County.

Nevermind that Johns died in 2015.

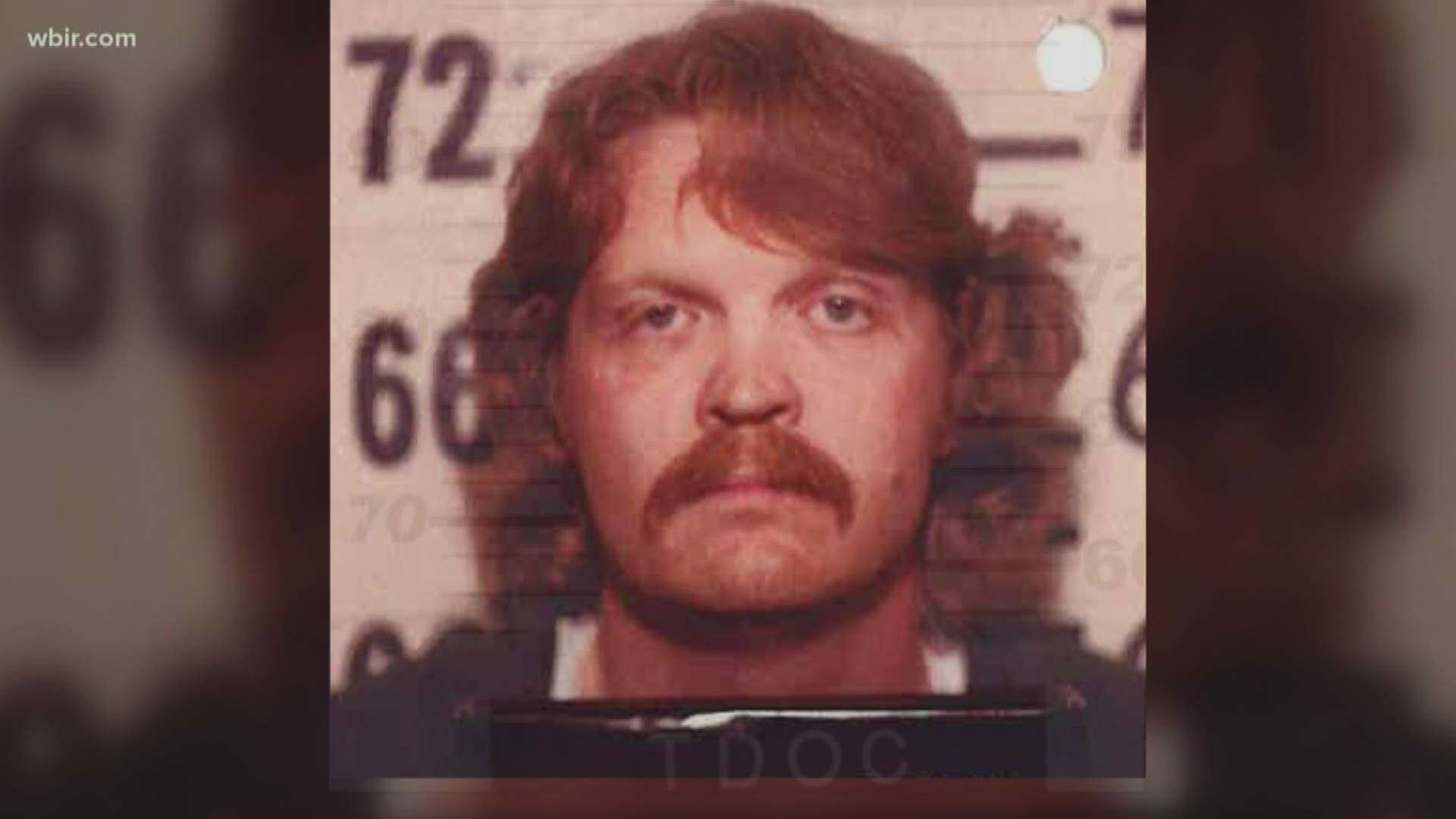

Investigators have always wondered about the independent trucker, who was convicted in 1987 of attacking a woman he met at a Knox County adult club. Even 35 years ago, there was speculation he might be the man behind what came to be known in the South as the "Redheaded Murders."

But he never was charged with murder. There never was enough evidence.

RELATED: Records offer chilling details about Knox victim's encounter with possible 'Redhead' killer

Today, the TBI is working to see if it can link Johns to other killings of women, who typically had reddish hair, found dumped near highways and roadways in states like Tennessee and Kentucky.

"Could he be involved in other cases?" TBI Special Agent Brandon Elkins said. "I think it's possible. Are we going to get there? I don't know, but we're not going to stop trying to connect anything we can connect."

Significant advancements in forensic science make it easier to prove -- and disprove -- any involvement Johns may have had with past redhead cases. That's assuming evidence from those old crimes can still be found.

It was years after the Campbell County killing that authorities were able to show DNA found on the victim's shirt and the blanket she was wrapped in came from Johns. Back in the 80s, the testing tools available were more limited and primitive.

So, who knows what else police and the TBI may learn about Jerry Johns and a handful of unsolved killings of female victims.

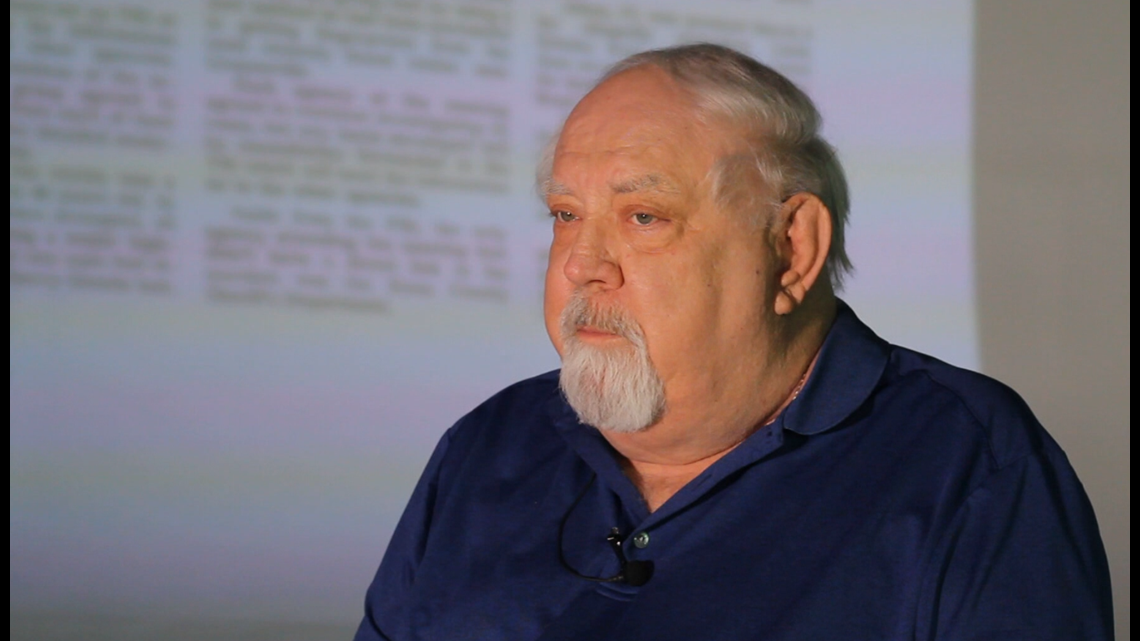

Dave Davenport, a former TBI agent and sheriff of Jefferson County, was part of a task force that met several times in the 1980s so law enforcement departments could share information and brainstorm leads about the women.

He doesn't know if the TBI will be able to tie Johns to any unsolved killings. Johns certainly had the personality of someone who thought he could get away with murder, he said.

It's also possible police caught Johns before he could kill anymore, Davenport said.

Johns was arrogant and condescending with the cops. He acted like he was smarter than everyone else, and boasted about his knowledge of serial killers, Davenport said.

"You never know what evil lurks in people," he said.

Bodies off the interstate

Local interest grew intense in the 1980s as women's bodies started turning up -- in the South and elsewhere. Often they were found along highways like Interstate 81, Interstate 75 and Interstate 40.

Often the women had been bound and strangled. Often they had red hair, which led to the "Redheaded" nickname.

Davenport recalls that local law enforcement became aware there might be a trend after the discovery of the woman's body beyond a guardrail off I-75 on Jan. 1, 1985, near Jellico.

They couldn't identify her, and wouldn't be able to for decades. She'd been dead a few days, an autopsy determined, and she was pregnant.

"We started going to places all over Kentucky, trying to identify her and putting up posters," he said. "Then we started hearing from Kentucky state police who said, Yeah, we have one (a female homicide victim) on the interstate."

Authorities in Arkansas, Mississippi and Ohio started comparing notes about their cases.

Looking back, Davenport and Elkins say it's clear the crimes weren't all related. It's logical, however, that some shared key links.

Nudged in part by heavy media play, Davenport said, area law agencies met several times as a "task force" to talk about the killings. According to Davenport, the gatherings actually produced little progress in terms of solving major crimes.

In March 1985, attention began to focus on Johns after he was arrested driving the car of a dancer he'd picked up that night at a notorious "adult" club called the Katch One north of I-40 near Lovell Road.

The woman told police Johns had tried to strangle her and left her for dead in a culvert off I-40.

An interesting detail, according to Elkins: She had reddish hair.

'Strangled to unconsciousness'

The woman known as "Tasha" danced nude at the Katch. It was a lucrative profession, sometimes bringing her a thousand dollars a week.

Johns, then age 36, ran his own small trucking operation, called Rebel Trucking Company out of Cleveland, Tenn.

He and his brother Wayne Johns went to the Katch the night of March 5, 1985. Johns had his own Katch membership card.

The dancer agreed to go with him to a Knoxville motel after work for sex for $200. Johns tore two $100 bills in half and gave her two halves, according to records. She would get the other two halves later at the motel, he said.

She helped arrange the services of another woman to have sex with Wayne Johns, court records state.

Everyone drove their own cars to the Holiday Inn on Dale Avenue, a business that's now gone.Tasha hid the two halves of her $100 bills in her Datsun 280Z.

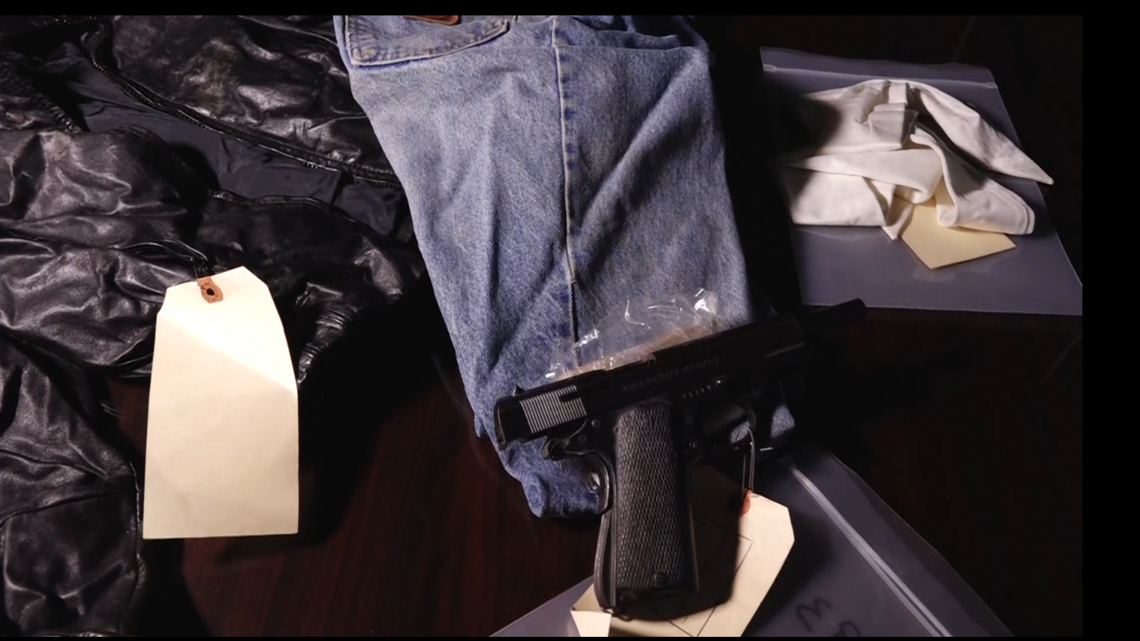

Johns got adjoining rooms for him and his brother, according to records. He had a gun, and told the dancer he was an undercover Texas Ranger, which was a lie. He drove a pickup with Texas plates.

After they had sex, she took a bath and prepared to leave. Johns had other ideas. When they walked to her Datsun, he forced her to move over so that he could drive. He'd never given her the other halves to the $100 bills.

Johns drove back to the Katch.

While parked in the club's parking lot, Johns ripped Tasha's T-shirt into strips, which he used to tie her hands and feet, records state.

He put a gag around her mouth and threatened to kill her if she tried to leave or screamed," an appellate opinion states. He headed west on I-40, finding some woods where he pulled the sports car over.

He forced her to go with him into the trees. She asked him if he was going to kill her, and he said yes, Elkins said.

"She said why, and he said, You've become a nuisance," the agent said.

He also was angry, she told authorities, because he'd discovered she wasn't a real redhead. She colored her hair, Elkins said.

Johns taunted her with his pistol. But rather than shoot Tasha, he wrapped a strip of her shirt tightly around her neck and strangled her until she lost consciousness.

Survival, a chase and a capture

She survived, however.

She would later tell authorities she came to in a culvert, crawled out of it and made it to the interstate where she flagged down a trucker.

"She told him and others who stopped to help that someone had tried to kill her," court records state. "She was fearful of her benefactors and begged them not to kill her."

Tasha told troopers who responded to the scene what had happened. She said Johns had driven off in her Datsun, and she gave the room numbers at the Holiday Inn on Dale Avenue.

The victim was treated at Parkwest Hospital off Cedar Bluff Road.

Knox County authorities headed for the Holiday Inn.

A trooper spotted Johns' pickup in the parking lot. A deputy joined him. The men saw the Datsun approach the lot but then suddenly speed off.

A chase ensued on nearby I-40.

After getting off at the business loop exit, the 280Z crossed the median and slid across another exit lane before coming to a rest. Inside the sports car, police found Johns' loaded gun.

During questioning, authorities found that Johns had a Holiday Inn motel room key, $752 in cash and the Katch One membership card. They saw him wad up and throw away several $100 bill halves.

The jury found the evidence was enough to convict Johns of the crimes. He received a long sentence behind Tennessee bars.

Friends and family members tried to convince the Knox County judge to show mercy. They insisted Johns was a good man who looked after his family.

They wrote that he and his wife had gone through hard times, losing a young son to a disease.

Few mentioned that he had a felony criminal record out of Mississippi.

The long-sought break

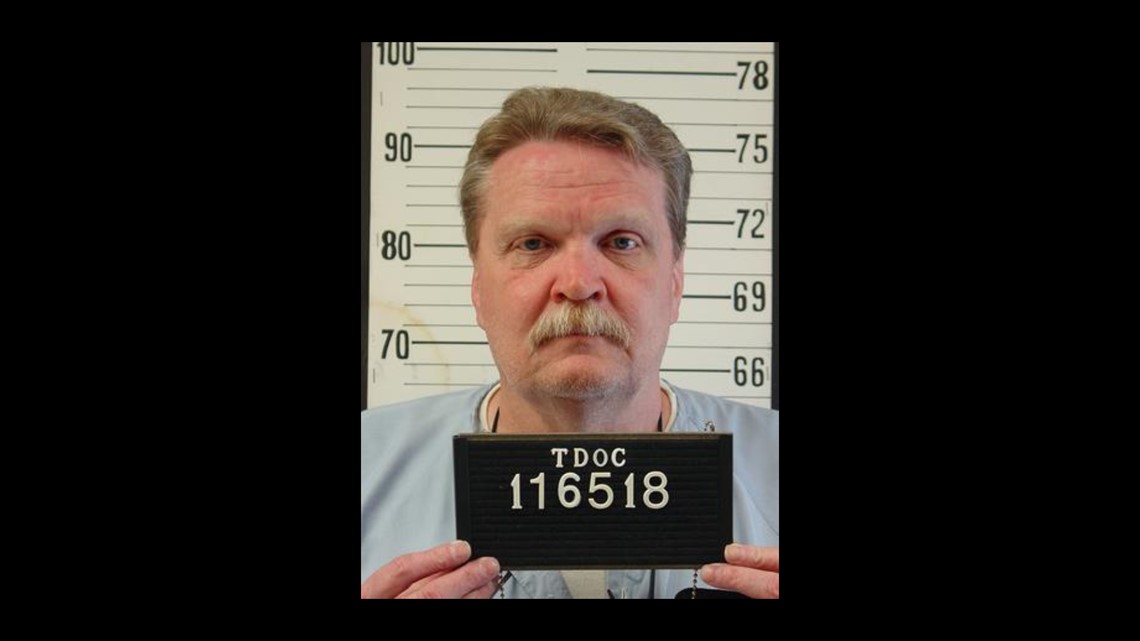

Johns never would leave prison after his 1987 trial in Knox County Criminal Court. He tried.

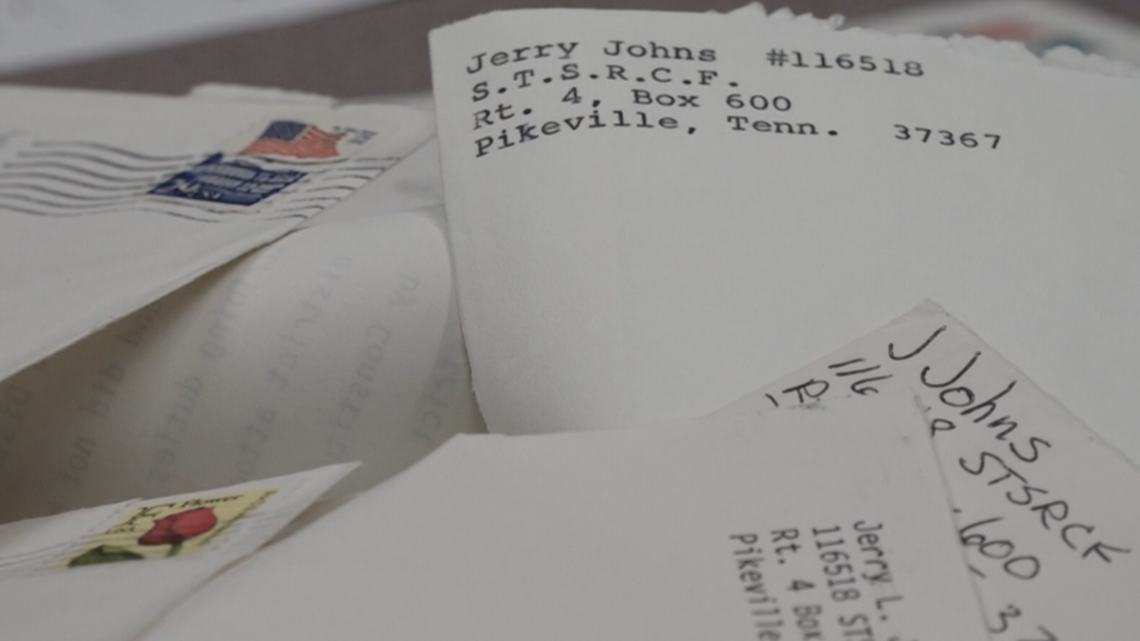

He hand-wrote numerous petitions insisting he should be released because authorities had the wrong man.

In February 1986, the woman known as Tasha sued Johns in Knox County Circuit Court for suffering, physical and emotional, that he'd caused her that night in March 1985.

Johns then turned around and sued her in July 1986 in the same court.

"It is the contention of plaintiff, Jerry L. Johns, that defendants...and (her lawyer) conspired to perpetrate a fraud upon the plaintiff..." his handwritten complaint states.

WBIR sought to speak with the victim for this story. The TBI contacted her, and she said she wasn't ready to talk publicly, according to the TBI.

Johns sometimes talked with the media after his arrest, complaining about how the police were portraying him. He'd never done anything, he insisted.

Working against investigators at the time was a relative lack of physical evidence.

Or so they thought. Because as the 80s passed into the 90s and then into the 2000s, forensic science got better. Analysts became able to identify suspects through their DNA, and they built up a national database of that information that could be used by agencies across the country.

The Campbell County case had particular meaning for Elkins. Before he went to the TBI, he worked for the Campbell County Sheriff's Office, and the homicide victim was one of his cases.

He never forgot about the bound woman in the blanket. He kept on working it when he moved to the TBI.

In 2016, he resubmitted the blanket and shirt to the TBI crime lab for fresh testing. Elkins got the break he'd been seeking.

Testing showed Johns' genetic profile, which by now was part of the national database, was found on both items.

Now the agent knew: Johns indeed had killed the redheaded woman found dumped over that guardrail near Jellico.

Unfortunately for investigators, Johns was gone, having died in prison in 2015 at age 67.

"It was a surreal moment to discover after all those years that we had identified who this killer was, but it was deflating to know he had died just shortly before the discovery of this DNA," Elkins recalled.

Said Davenport, one of the original TBI investigators: "I'd like to have seen him alive and been there when they said, Jerry, we have your DNA on the blanket you wrapped (the victim) with. Your butt is going to jail, or the electric chair.

"I'd like to have seen that cocky smirk come off of his face."

Another break would follow in 2018. The TBI got a tip to look at an amateur website that offered information about missing people.

That led them to confirm that the Campbell County victim was Tina Marie Farmer, age 21, who had been missing for years in Indiana. TBI intelligence analyst Amy Emberton tracked down a 1984 fingerprint card for Farmer that matched the Campbell County victim.

It's that kind of break that gives investigators hope they can solve other old cases.

"At this current time we have not made any connections anywhere in the nation connecting (Johns) specifically by forensic evidence to another case," Elkins said. "But we are definitely open to the possibility that he could have killed before Miss Farmer and before the victim here in Knox County was assaulted."

The special agent said the TBI is "actively" working on all its unidentified female homicide victims to ensure their DNA profiles are submitted and available in the national database accessible to law enforcement.

"We're going back over cold cases that may have similar facts to them, to see that evidence has been submitted," he said. "We're doing that with all of our cold cases."

There's a real possibility they'll find that Johns may have committed more killings, Elkins said, "but in the end, that will come down to good law enforcement work as well as help from the public."