ELK VALLEY, Tenn. — Her resting place was so remote the person who dumped her body had to have used a four-wheel drive to get to the scene.

So remote that the nearest human being who could have helped her lived far down the Campbell County mountain.

At the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, they call the unidentified victim from 1985 “Baby Girl,” because they know so little about her. And they always want to remember this: They’re dealing with a dead child.

“To think about a kid going through something so horrible at such a young age,” said TBI Special Agent Brandon Elkins, the father of three children himself. “Innocence changes our perspective on cases. All homicides are bad, but when you have a child who doesn't deserve to murdered and discarded in this fashion, it changes everything about it.”

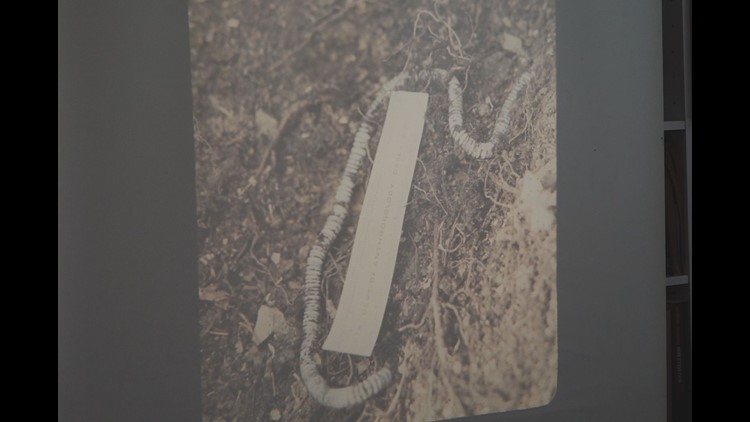

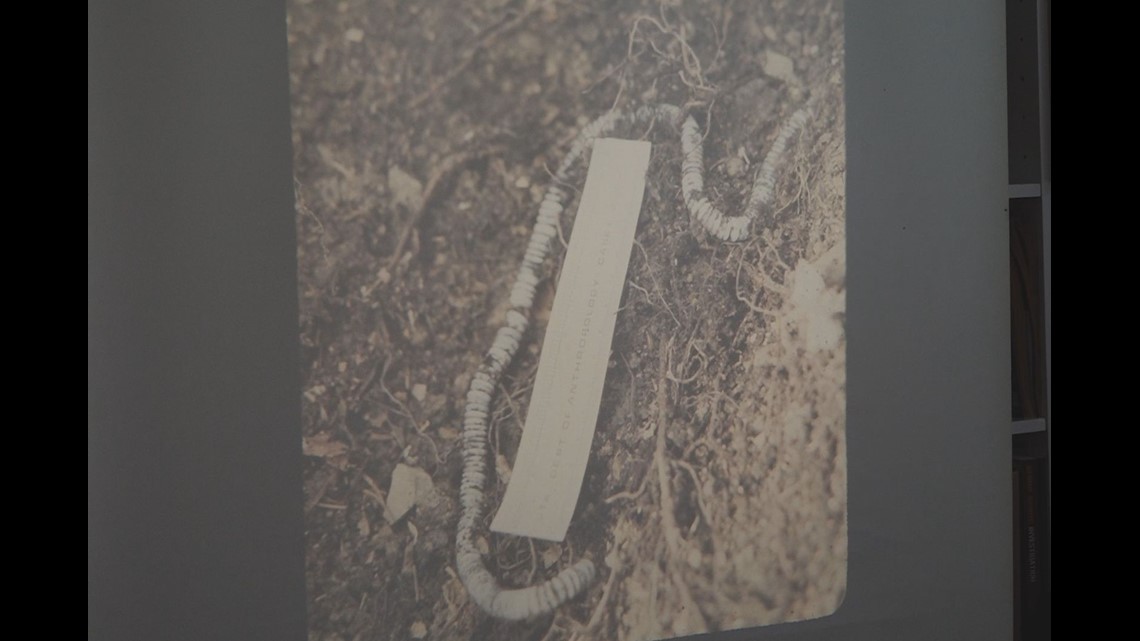

Today, all the agency has to go on to identify her – and maybe one day find her killer – is her brownish, whitish skull, some finger bones, some ribs, a bracelet, a plastic puka-like necklace, two girl's high-top sneakers and a couple scraps of cloth.

It isn’t much. Elkins will take whatever he can get. He’s hoping that with modern investigative tools there’s a chance he’ll be able to narrow down where she came from and who she might even be.

Author and renowned forensic anthropologist Dr. Bill Bass worked on the case 35 years ago, keeps his own file about it and remembers it well. It’s one he’d like to see solved.

Whoever tossed the 10- to 15-year-old Baby Girl in the mountains about mid point between Caryville and Jellico knew exactly what he or she was doing, said Bass, who's reviewed scores of homicides and unexplained deaths.

“This is not the typical body you find thrown off the interstate,” Bass told 10News.

ALL ALONE

Back in the 1980s, heavy trucks moved up and down the pitted, rutted Sand Gap Road above the Elk Valley community. They hauled logs and coal.

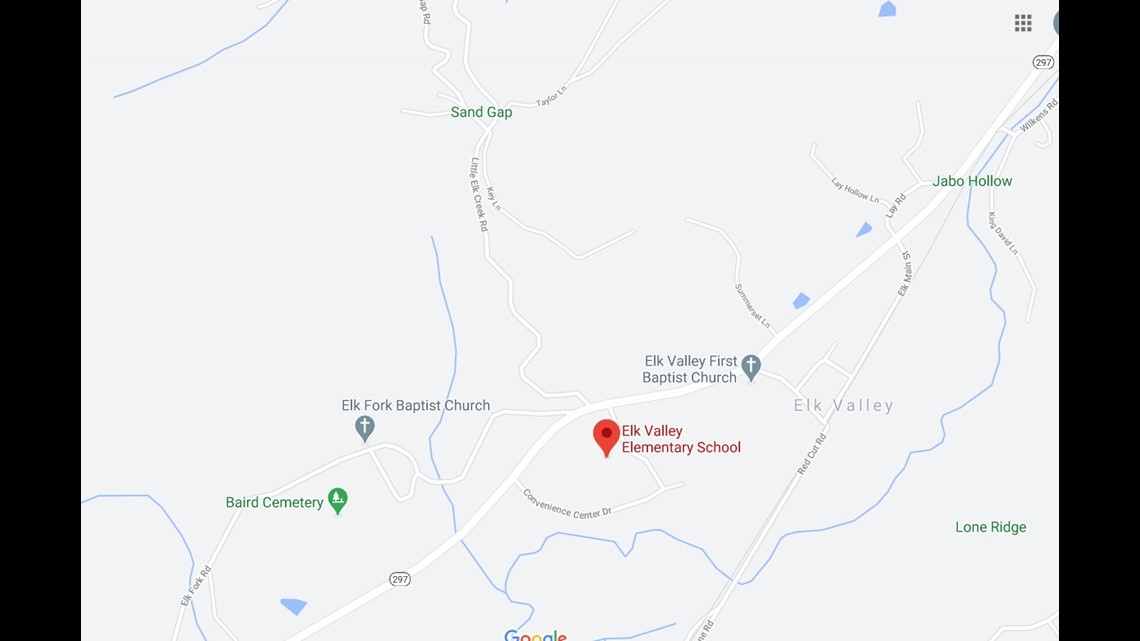

Today, the isolated spot where the girl was found is in the path of giant TVA power lines that start at the top of one mountain, stretch down a steep footprint into the valley and then climb back up to the next mountain.

People live down below. No one lives up here.

The nearest access to Interstate 75 is 12 miles away on the winding state Highway 297-- past Elk Valley Elementary, farms, homes and vacant land. By foot, the Kentucky state line is probably five or 10 miles away.

It’s the kind of heavily wooded, cast-off place a litterer might go if he was too lazy to drive to the dump. It’s the kind of place only a local would remember.

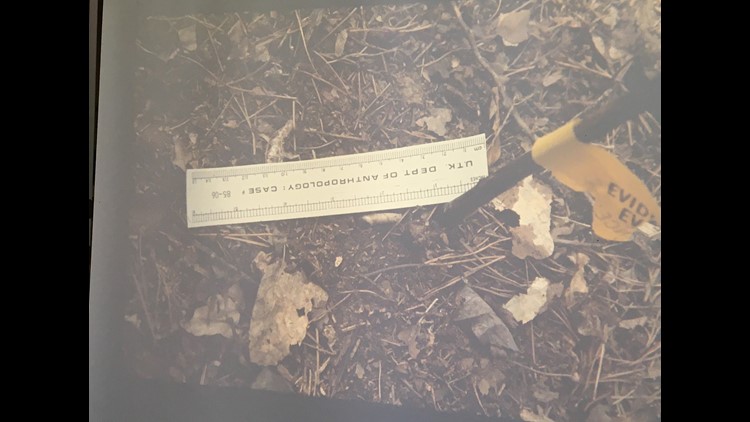

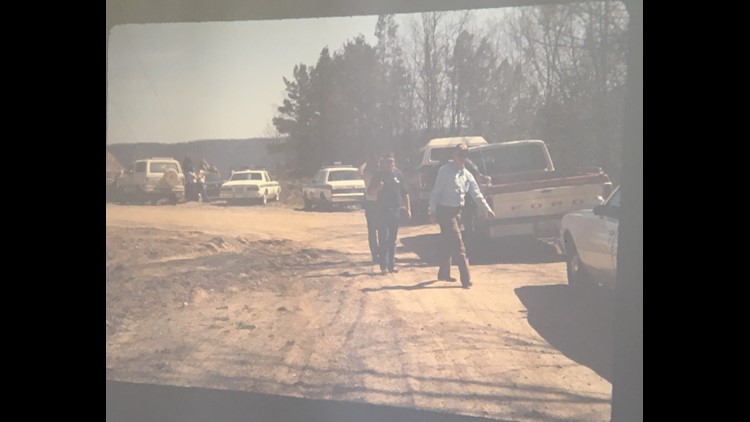

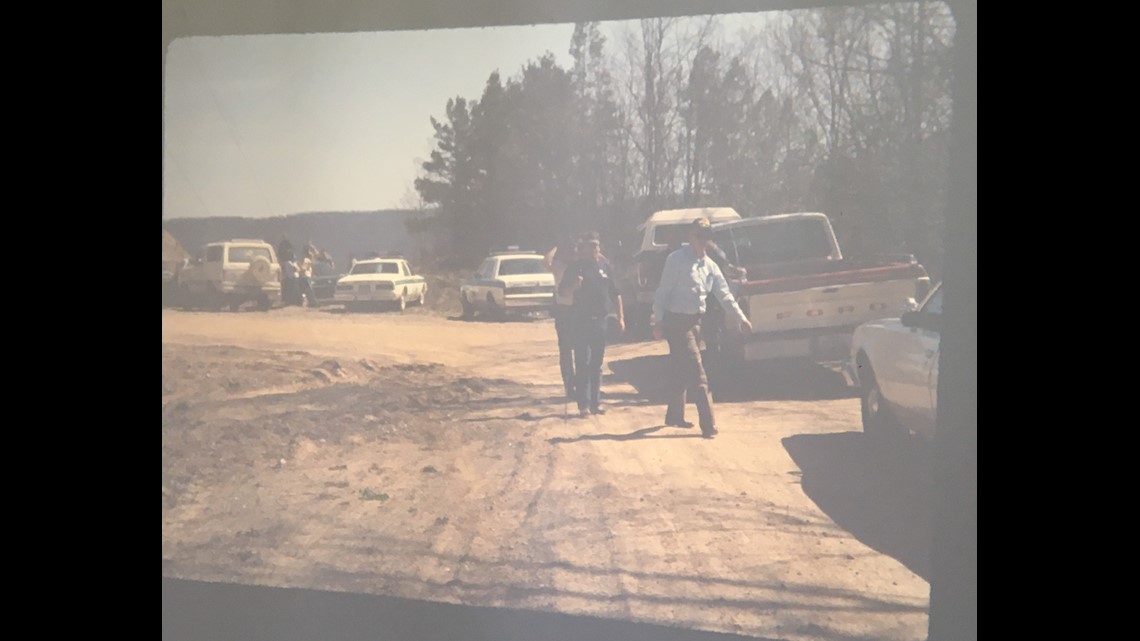

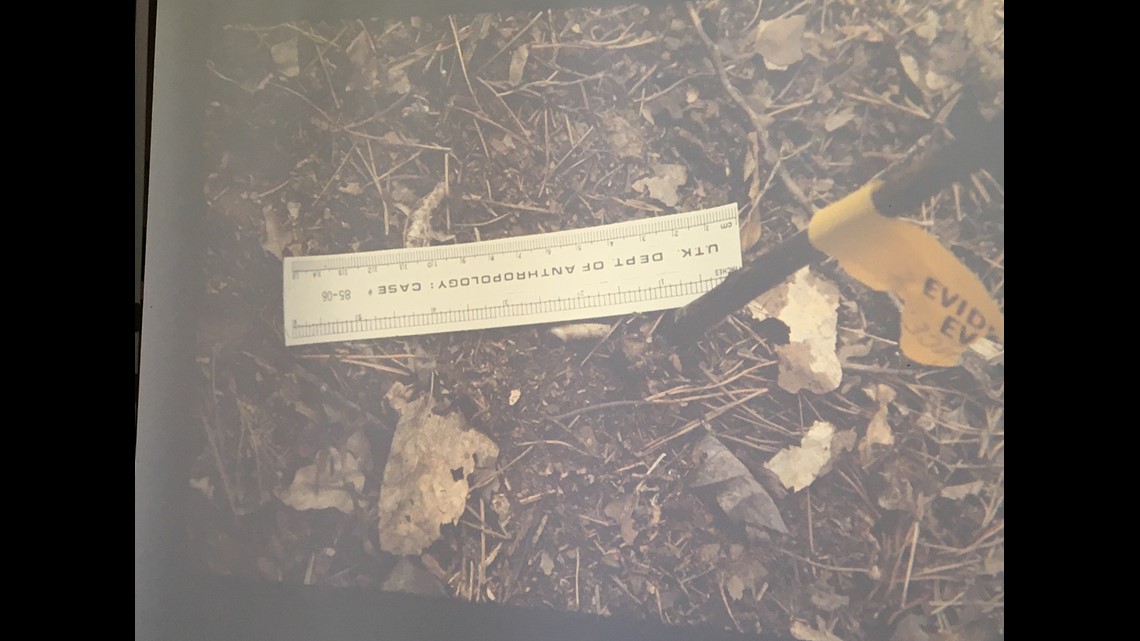

A person hunting for pokeweed found the girl’s skull in early April 1985 in woods below an old strip mine clearing, Elkins said.

Campbell County detectives brought the skull to the University of Tennessee’s Anthropology Department deep beneath Neyland Stadium.

The next day, more bones were found scattered in the underbrush.

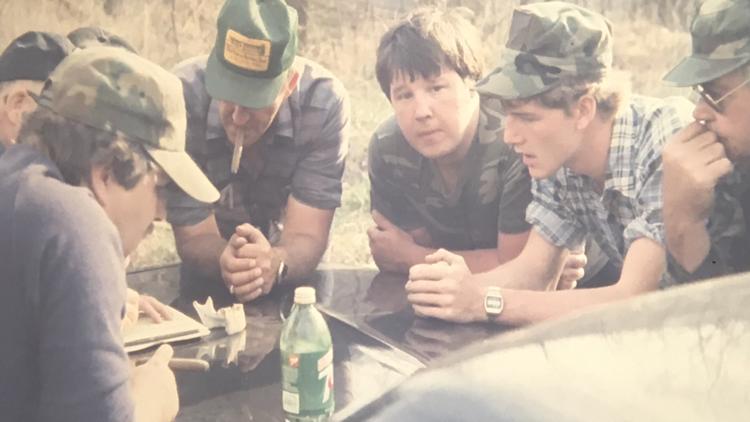

Bass and three graduate students headed up to Campbell County to see what they could find for themselves. They collected more remains from the scene and headed back to campus to figure out what they could from the bones in hand.

Locally, detectives found nothing that linked the remains to anyone missing in the area.

Down in Elk Valley, residents could offer few clues themselves. They certainly couldn’t think of a child who might have gone missing.

"There's something wrong with this picture," Bass said. "It does not fit the normal."

THE REPORT

Memories grow fuzzy. Documents don’t.

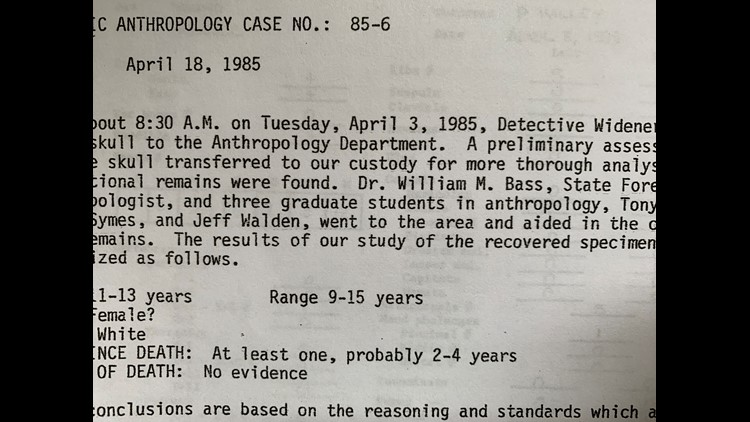

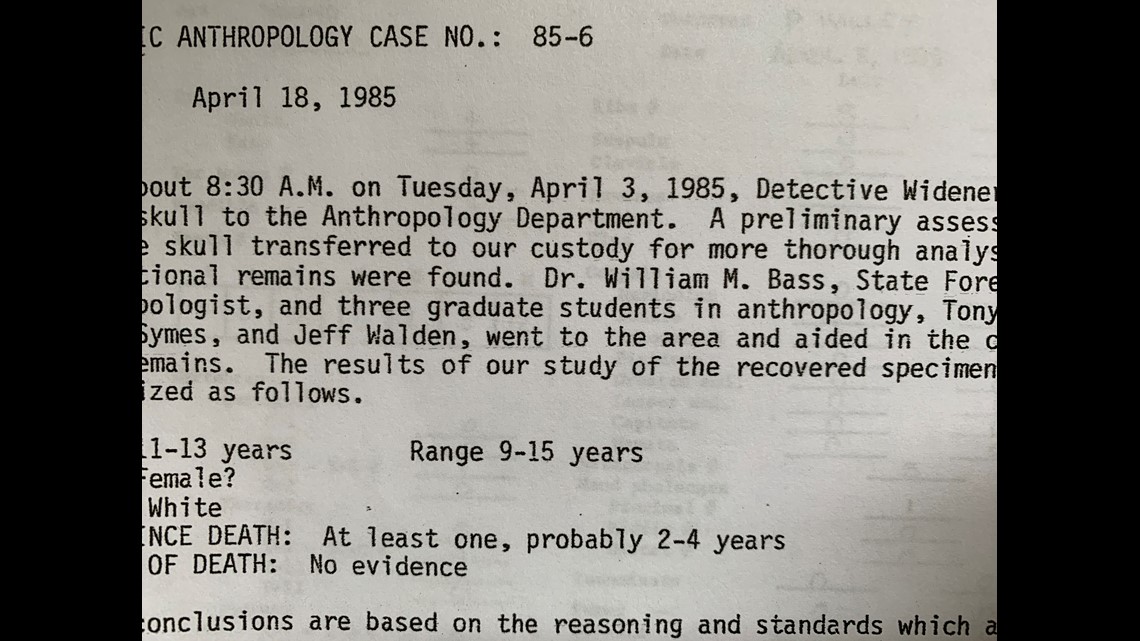

Some of the best details and most concise information about the Baby Girl case are contained in an April 18, 1985, forensic report prepared by a forensic team. Bass keeps a copy of it to this day in his West Knox County home.

Here’s what Bass and his team determined:

While the skull was found in April 1985, it certainly had been there a lot longer.

“Animal chewing, typical of a dog-sized creature, is present on some of the postcranial bones,” the report states. “This chewing indicates that the body was eaten – at least in part – by scavengers.”

Grass seeds in the orifices and a wasp nest inside the skull, which had been lying on its left side, indicated it had been outside for at least nine months, the report states. UT entomologist and associate professor Harry Williams said the nest appeared to have been made by a paper wasp.

Paper wasps like to build nests on dry sites; a skull can take a year or more to thoroughly dry, the report states.

It stood to reason then that the skull could have been on that slope since summer 1983 or longer.

“Because of the variability in decomposition and weathering rates, estimation of time since death must remain tentative,” the team wrote. “Nevertheless, it appears that the remains have been exposed more than a year and may have been out for as many as three to five years.”

That the remains were those of a young girl isn’t really in doubt. They clearly were those of an adolescent, and feminine traits noticed in the skull such as the pointed chin and small brow ridge suggest it belonged to a female, the report states.

Her age at death also appeared pretty easy to narrow down.

Measurements of the teeth – 22 were found intact – and what’s known about how teeth grow indicated the child was probably age 11-13 with a possible age range of 9-15.

Her four wisdom teeth still hadn’t emerged, the exam found.

Also, the “sutures” in her skull -- such as at the roof of her mouth -- hadn’t fully grown together, another sign she was still an adolescent. Until someone reaches adulthood, there still are areas of the skull that haven’t fully merged.

Investigators, however, lacked evidence to say how she died.

Other parts of the skeleton maybe could have offered clues about a possible gunshot wound or blunt force trauma. If they existed, however, they’d long since been dragged away by the animals.

Appalachian Unsolved: The girl in the woods

CLUES

Whatever happened to Baby Girl, forensic science and modern technology do offer some ideas of who she may have been.

Bass said she’d had dental work – fillings were found if all four first molars, which typically emerge by the time someone is age 6 or 7. Someone had cared enough to get her to the dentist.

Also, her lower front teeth were uneven.

Given the right dental X-rays, it should be possible to confirm her identity, the report states.

"We wrote about 50 dentists in the Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina area, thinking this might be something local," Bass said. "We never heard from any of them."

The high tops, which had a red cloth lining, two pairs of eyelets and two pairs of metal hasps, offer another clue: They’re a woman’s size 5 or 6.

The necklace presents another clue: It’s made of what appear to be plastic “buttons.” It resembles a kind of puka necklace popular in Florida in the 1970s and 1980s.

Elkins said new developments in science also have been helpful. Isotopic testing examines the origins of food sources in remains, and it can help pinpoint where someone may have lived and grown up. In Baby Girl’s case, newer testing suggests she came from some place other than Tennessee, he said.

It could be Florida, for example, he said. Or, it could be a place like the Midwest or Colorado.

The agent hints that other technology advances also may offer clues in the coming months or years.

Data from the girl’s remains have been submitted to a database called the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, or NamUs for short. So far, however, there’s been no match with any known reports of unidentified people.

Elkins began working the Baby Girl case some 13 years ago when he was a Campbell County deputy. Before him, others did what they could to identify her.

Today, he continues to chase the case for the TBI.

While many years have passed, he’s convinced there’s still someone out there who knows something about the child and why she ended up dead.

The agent ticks off the scenarios he’s gone over so many times before.

Assuming she wasn’t from Campbell County, could she have been picked up somewhere else and then dropped there in death by a local who knew the area well?

Was she an unwanted child who no one ever bothered to go find?

Could it be that a trucker who knew the back mountain road from making trips to the mine saw it as a good place to dump a body?

“Someone somewhere has to know something about this girl,” he said. “A child just does not disappear without someone knowing. We hope we get something stirring and that someone points us in that direction."

If you have any information about this case, email the TBI at tipstotbi@tn.gov.