OLIVER SPRINGS, Tenn. — Little towns keep big secrets.

For more than 80 years, the murders of well-to-do spinsters Ann and Margaret Richards and their teen helper have remained unsolved in Oliver Springs, Tenn.

After all these decades, it's almost certain the killer never will be revealed.

The murders have been the subject of an inquest, a book, a song, a documentary, an exoneration and decades of whispered talk. All of that attention has failed to flush out the killer or killers.

Speculation always has focused on just a few possible suspects, including people who lived or worked within yards of the three-story Richards mansion perched above one of Oliver Springs' busiest streets.

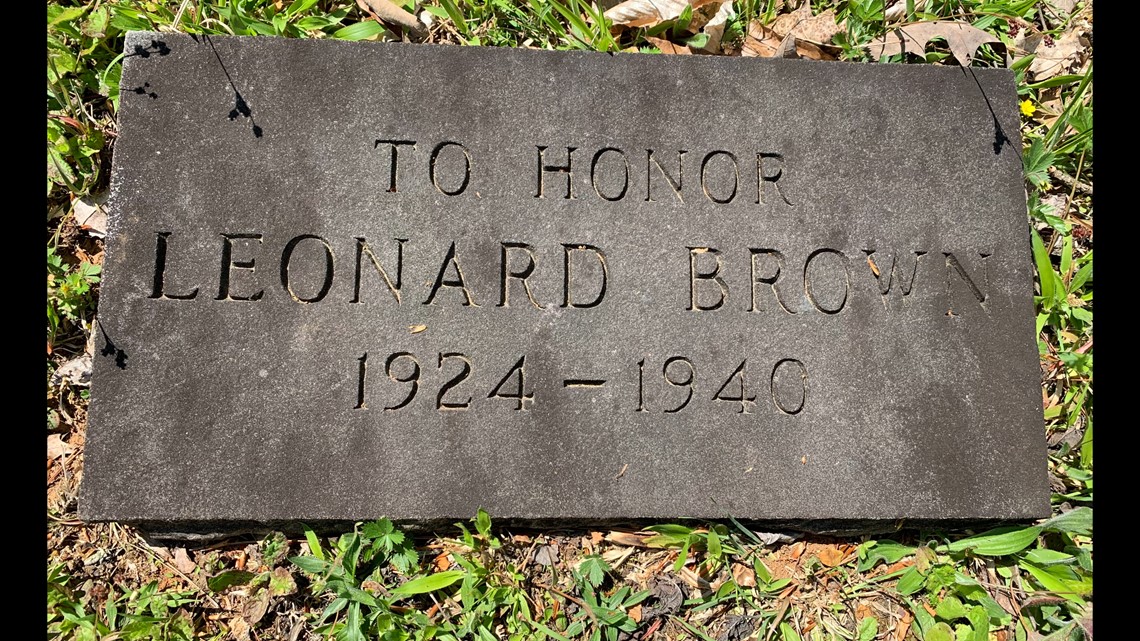

Whoever shot the sisters and 16-year-old Leonard "Powder" Brown on Feb. 5, 1940, left clues: an antique pistol placed by the Black teen's body, cigarette butts in an upstairs bedroom, nothing taken from the ornate home.

They also tried a cynical ploy that nearly worked, staging the murder scene to make it look like Powder killed the sisters and then turned the gun on himself.

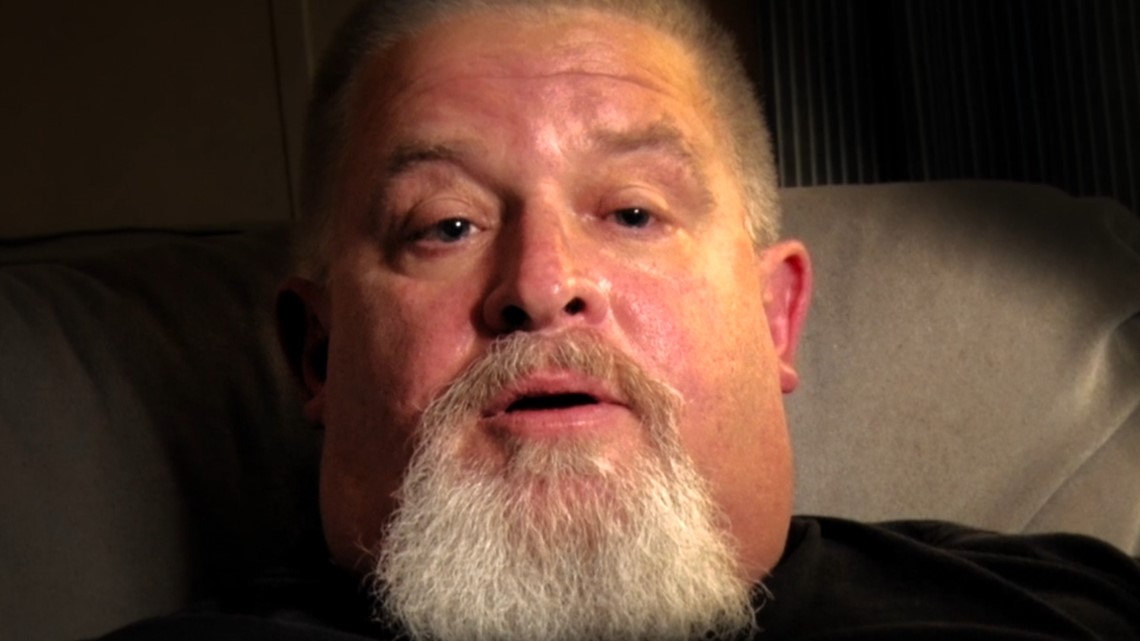

"People to this day still hold their tongue and don't talk about it," Oliver Springs Police Chief Paul Massengill, who formally cleared Brown in 2001, once observed.

The key suspects are all dead now. But members of their families survive. And that makes it awkward to talk about what happened.

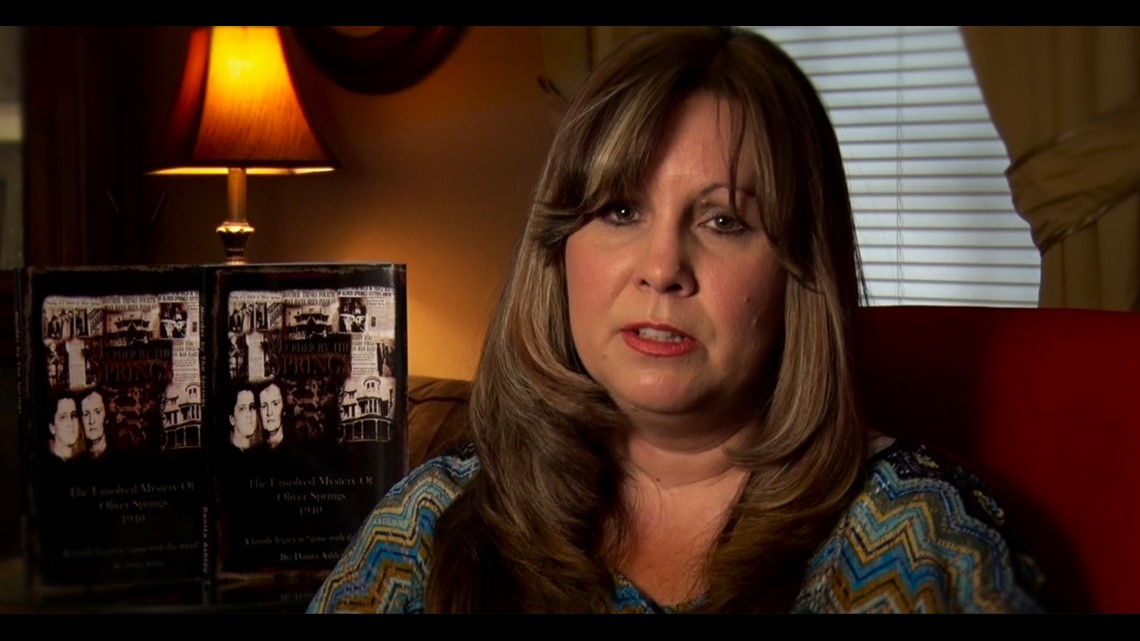

"There could be people still alive today that may know who done it, if they would come forward," said Danita Ashley, whose fascination with the tale compelled her to write a book, "Murder By the Springs".

"Getting them to come forward would be the thing."

MANSION ON THE HILL

Everyone knew the Richards family had money -- or at least once had money.

Patriarch Joseph Richards, a native of Wales, profited in the iron and coalmining fields and then bought land in Winter's Gap, now known as Oliver Springs, to build a resort hotel. It sat by the region's bountiful mineral springs, a magnet for people from across America convinced of their healing powers.

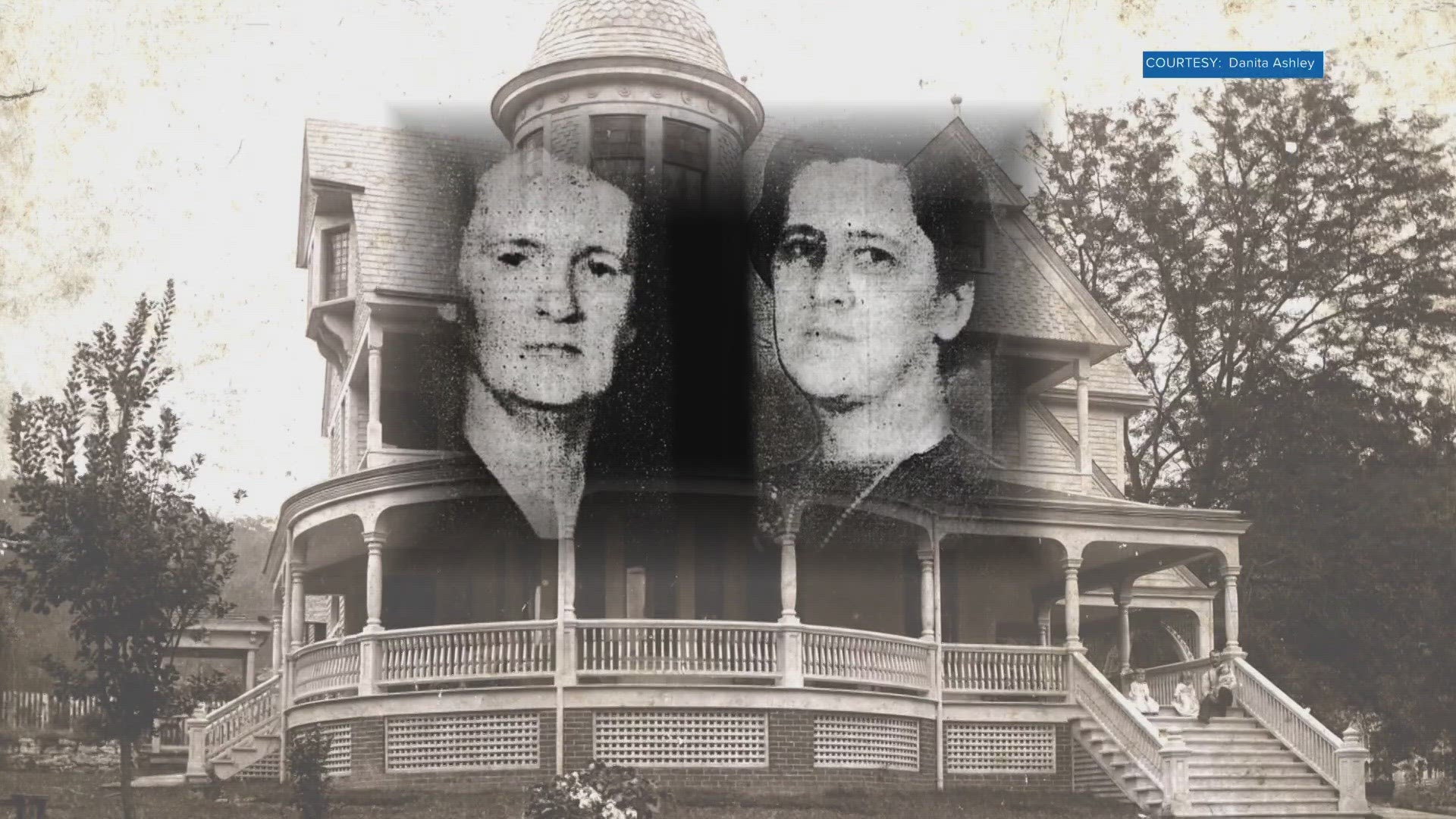

After the elder Richards' death in 1888, his sons and grandchildren carried on in Oliver Springs. They built a grand, 18-room home in 1893 on Main Street, with the hotel standing just about 100 yards off to the north, said Oliver Springs attorney, municipal judge and amateur historian Joe Van Hook . As often happened back then, the hotel caught fire in 1905 and was destroyed.

The Richards home featured a basement, a cupola that offered a sweeping view of the town, tiled fireplaces, hand-carved banisters, stained glass windows and a power plant in the basement for lighting, according to the Oliver Springs Historical Society.

In the town of less than 1,000, the family's wealth made them an obvious object of envy, maybe even jealousy.

After Joseph Richards' son William died in the 1930s, a cousin in the family, Mary "Mamie" Sienknecht, filed suit in Anderson County, challenging the senior Richards' will and land distribution.

She was smart with money; she lost the lawsuit.

By then, Joseph's granddaughters Ann, 48, and Margaret Richards, 46, shared the big old home with their younger sister, Mary, a teacher in town. They had a reputation for being kind and generous, even as their family's once significant wealth began to shrink with the passage of time.

MALIGNED IN DEATH

Ann and Margaret had a big night planned for Monday, Feb. 5, 1940. They were going to Knoxville to see "Gone With the Wind" at the Tennessee Theatre.

The sisters bought dresses especially for the occasion, Van Hook said.

Before then, however, they had duties to attend to at home. Their errand boy, Powder Brown, would be stopping by in the early afternoon.

The killer -- or killers -- chose the quiet of late morning to enter the mansion.

The gunman got Ann with one shot in the kitchen. Margaret suffered two gunshots, in the throat and head. Evidence at the scene indicated she may have tried to fight back. She was shot by the stairs.

Ashley said they likely were killed sometime between 11 a.m. and noon. A man from town stopped by sometime that morning to pay them for his child's piano lessons.

Powder Brown, a shy, timid teen, entered the home sometime after lunch expecting to help the sisters with routine chores. Instead, he encountered the killer, who shot him between the eyes while he was upstairs, Ashley said.

Younger sister Mary Richards sent children to check on the women that day while she remained at school. One of the boys would later say he heard odd noises inside, but no one would come to the door.

A woman stopped by the house around noon with a delivery. She knocked at the back. No one answered. She told the News Sentinel she distinctly heard the voices of white men inside.

It was Mary herself who discovered the crime when she came home that afternoon. She found Margaret in front of the staircase in a pool of blood.

"Her screaming was so loud you could hear it all over town," Massengill later recalled.

When the police arrived, they found an old pistol by Powder Brown's body. The local mortician recognized it; he'd once owned it but had later sold it to a member of the Hannah family, which just so happened to live across the street from the Richardses.

Police, friends, acquaintances -- people of all kinds -- wandered through the house, ogling the horror. Some passed around the gun.

The sheriff took one look at the crime scene and declared he could tell what had happened. Powder Brown -- who'd been at the Hannah home that very morning -- stole the gun, shot the sisters and then turned it on himself, the sheriff said.

He posed for newspaper photographers, holding the pistol out with his hand and pressing the barrel straight into his forehead.

"Sheriff Sure Negro Fired in Mad Rage," one front-page headline proclaimed.

Others had their doubts.

A coroner's inquest of 12 local men met to consider the evidence. They learned that no gunpowder residue could be found on the teen. They heard that the bullet's downward path through Powder's head didn't fit with that of a self-inflicted wound. Furthermore, the alleged murder weapon was an antique gun.

Perhaps most importantly, Ashley said, Powder Brown was afraid of guns. He was afraid of fireworks, and would run if he ever heard them, Massengill said.

The inquest rejected the idea of a murder-suicide.

"Even the people who were doing the inquest went and told the sheriff, 'We don't believe he did it.' The sheriff at the time said, 'Well, it's my call," Ashley said.

The sisters were buried in the brand-new dresses they'd planned to wear that night. They were laid to rest side by side in the Oliver Springs Cemetery in a family plot, their mother and father mere feet away.

Powder Brown's body was hustled out of town and placed in a remote graveyard surrounded by thick woods, lest anyone try to take vengeance. No known photo of him survives to this day.

Mary Richards moved to Atlanta to be closer to her brother, Joseph. The surviving siblings sold the mansion intentionally to the American Legion for $1. Fire destroyed it in 1947, forever wiping out further exam of any evidence that could have been recovered from the crime scene.

A WITNESS COMES FORWARD

Doubts about the Richards murders never left Oliver Springs. That tends to happen when people know what really happened but are too afraid to say.

Clearly, the attacker wasn't after property. Nothing was taken from the home, Ashley said. Cigarette butts found in an upstairs bedroom suggested someone had placed themselves in a key vantage point from which to watch the comings and goings outside.

One persistent theory held that someone in the Hannah family across the street might have been involved because they'd engaged in a property dispute with the Richardses at one time, Van Hook said.

And, there was the fact of the pistol owned by a Hannah family member being found with Powder Brown's body.

Speculation also persisted that two Black convicts might have killed the three while stopping in town after recently being released from Brushy Mountain state prison.

Then, in 2000, a Black man who had once lived in town came forward. He told a local journalist he'd fled town decades ago as a young man because he'd seen two men leaving the Richards mansion around the time of the killings. Those men had spotted him and told him if he knew what was best, he'd forget ever seeing them and leave the area as soon as possible.

He only came back when he knew the men were dead.

Massengill, the new chief of police, spoke to him then. The chief, who died in December 2015, recalled the conversation for a documentary that Ashley's daughter, Tara Tinker, made following publication of her mother's book.

"He was still afraid all those years later," Massengill said.

The man's story convinced the chief to look deeper. He came to two conclusions: Powder Brown couldn't have been the killer, and two local men and Sienknecht the cousin who lost her bid to get family property likely were the perpetrators.

Sienknecht by then had been dead more than 20 years. Curiously, one of the male suspects ended up killing the other with a gun, perhaps because he was about to spill what he knew, Massengill said.

"He got dealt with the same way the Richards sisters did," he said. "He was disposed of -- shot and killed. Can't talk no more."

REMEMBERED IN SONG AND STONE

For years, Powder Brown rested in a tucked away cemetery with no stone whatsoever. Thanks to a member of the Richards family, one was placed about 20 years ago in the cemetery where he resides southeast of town. His exact whereabouts are unknown.

It's not clear who is still alive from his family. Ashley said he was an orphan at the time he died, well-known around town but mostly on his own. Next year marks his 100th birthday.

The young murder victim is remembered, however, in a song written by East Tennessee musician Kipper Stitt of the band Pine Mountain Railroad.

"Still in his teens, no evil he done.

Powder was timid, just ask anyone.

Three lay dead, three were slain.

Someone was guilty, was Powder to blame?"

The sky was so dark and the bitter winds blowing...

on a cold winter day in 1940."

Before he died, Massengill told Tinker and Ashley that the killers tried to make a scapegoat of Powder Brown. He said he was glad he could clear the young man's name for the injustice put upon him all those decades ago.

"The Black man didn't have any power," he said. "Women didn't have any power. The white man had all the power. Can't prove who did it, but I think I know, in my opinion, who did it.

"That's just where we will leave it -- in the history books that way -- able to clear Powder"