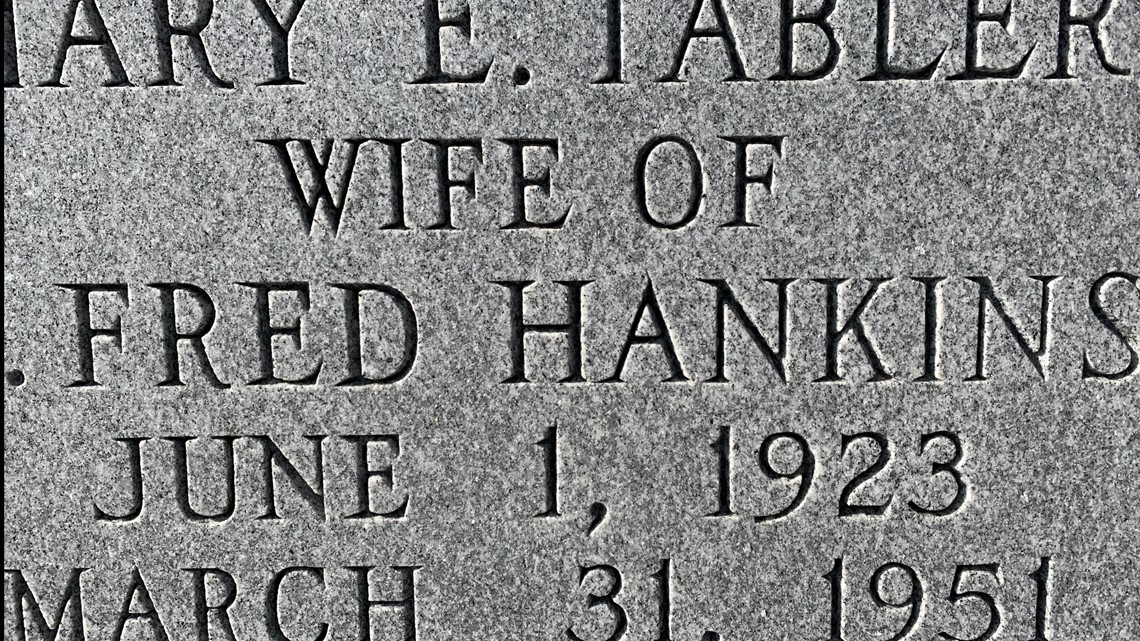

KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — Mary Hankins' face looks out sweetly from her gravestone.

It's a tinted image, brushed in hues of pink and black, pocked by decades in the East Tennessee seasons. It's easy to spot the marker, looming over her kin's plot in the Graveston Baptist Church Cemetery off Tazewell Pike.

Only her killer may know why Mary, 27, had to die.

On a Saturday afternoon in March 1951, she was minding her own business when a gunman entered her new Fountain City home, shot her once in the head and left her to die.

Her husband of four-and-a-half years, Fred, was down the road from their Harrill Hills house tending to an errand. A neighbor working in the yard across the street would later tell police she'd seen a tall man in a blue suit park a dark car and go inside the Hankins house. He stayed for a bit and then briskly drove away.

Her homicide -- so startling in post-war, suburban Knoxville -- ended up pitting newspaper against newspaper and agency against agency. Police and politicians dangled reward money as bait to get tips but never could crack the case.

The Knox County sheriff drew jeers from one paper for failing to catch the gunman. The case contributed to him losing his job.

For a decade or so afterward, the public would be reminded of the inexplicable killing of Mary Hankins. And then with the passage of time, the world mostly moved on.

The house still stands, nestled on a winding, secluded road. There's no trace of what took place there.

A .32-caliber Colt pistol found in a creek months after Hankins' death -- the likely murder weapon -- has been lost. The investigators are dead. Files have disappeared. 71 years later, the killing will likely never be solved.

No one is left to speak for Mary.

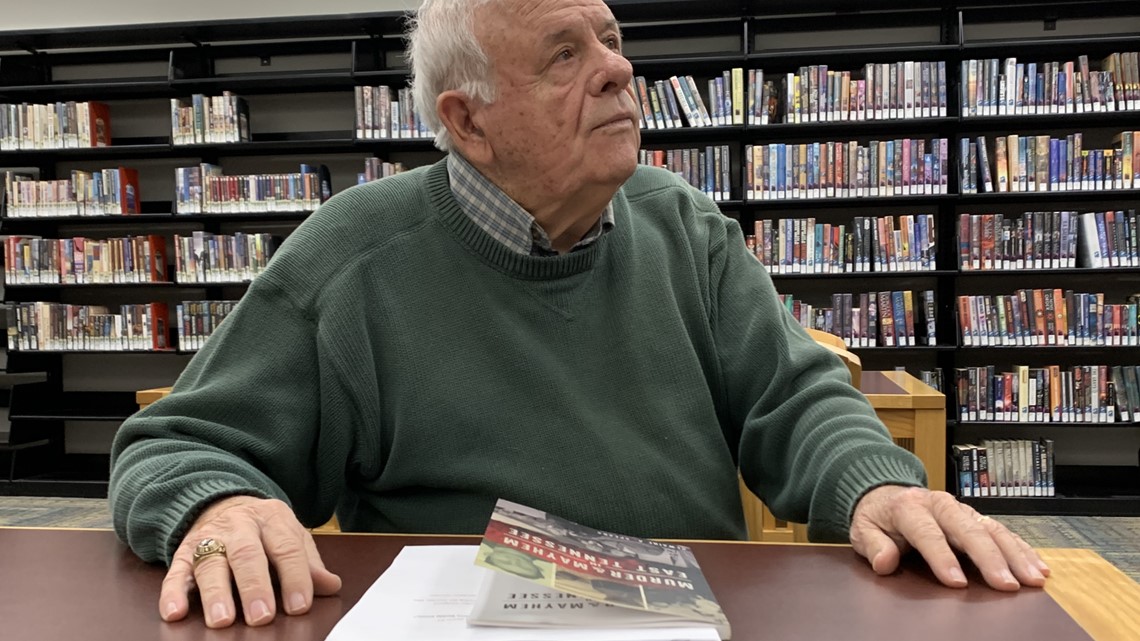

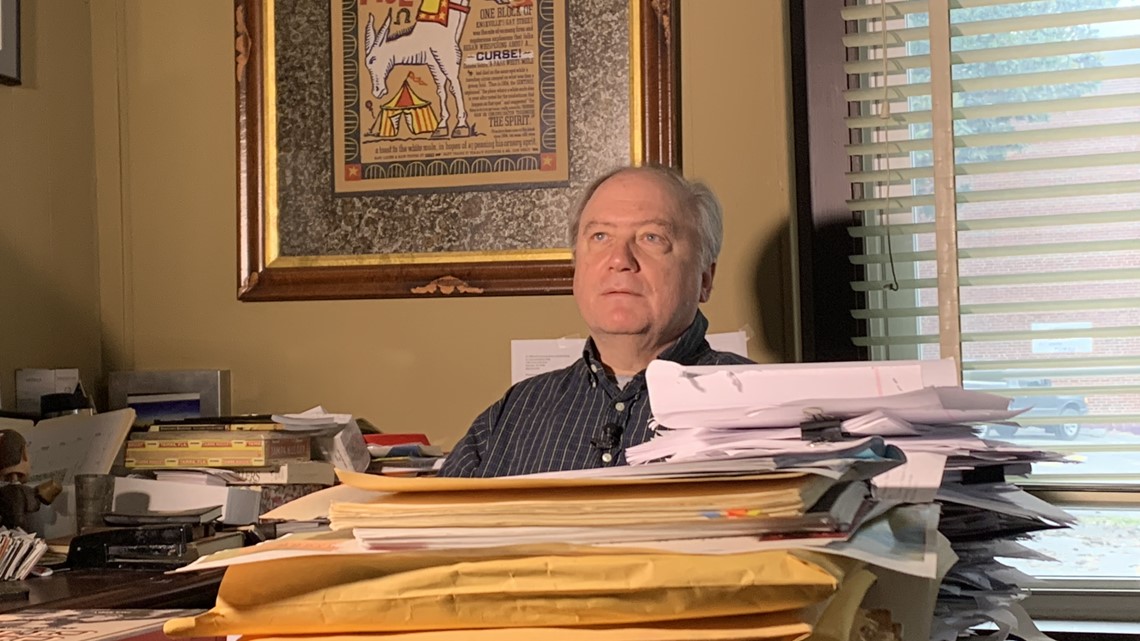

Now in his 80s, author Dewaine A. Speaks was a Fountain City boy when Hankins was killed. It shocked the community, said Speaks, who included a chapter about the case in his book, "Murder & Mayhem in East Tennessee".

"They started locking their doors," he said. "Before that people didn't even lock the door."

The Hankinses were living out the American Dream, Knoxville historian Jack Neely said. Why anyone wanted to end it is a puzzle, he said.

TALL MAN IN A BLUE SUIT

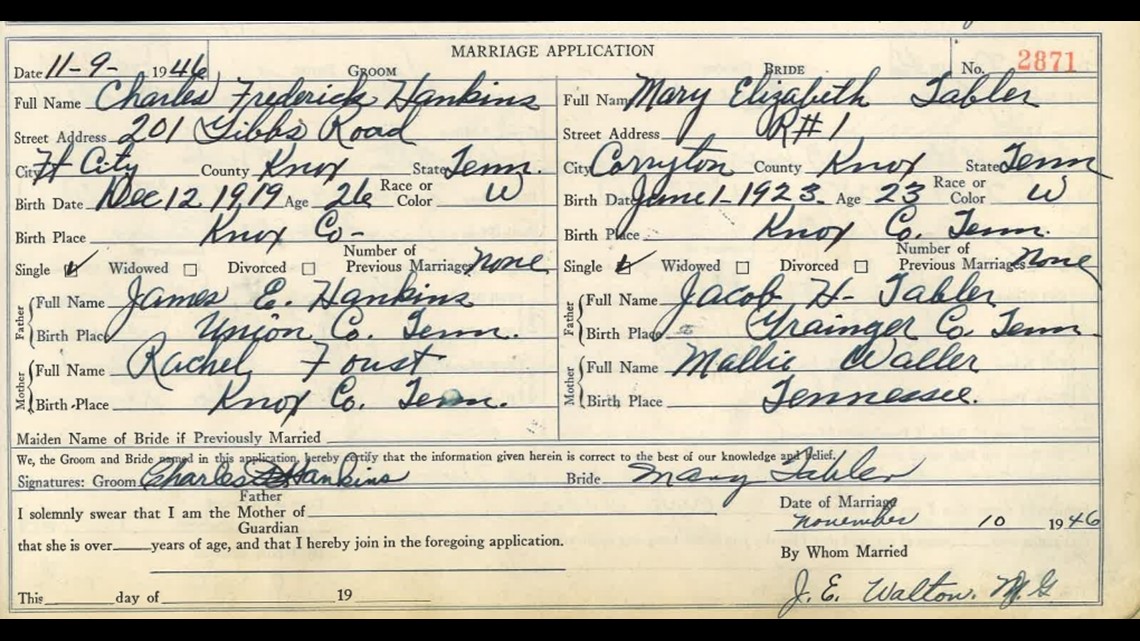

Mary Tabler of Corryton and Fred Hankins of unincorporated Fountain City married in November 1946. He was 26; she was 23.

In late 1950, the Hankinses moved into a new brick home. By spring, they still were working on the yard; dirt piles dotted the lot.

He worked in construction services. They had no children.

About 5 p.m. March 31,1951, a Saturday afternoon, Fred was in Fountain City getting his car repaired. Mary prepared dinner at home.

The killer, according to reports from the Knoxville Journal and the competing Knoxville News Sentinel, appeared to have arrived while Mary cooked a chicken.

Quoting the county coroner, Sidney Wolfenbarger, the papers provided readers with details that authorities would never, ever make public today.

It appeared there'd been a bit of a struggle in the house before the gunman shot Mary from an angle almost straight down into her head above her left ear. She was found lying on her right side.

She may have tried to escape, getting to the steps that led down to the basement garage. Blood dripped down the stairs, but there appeared to be no spattering.

A dishtowel rested on the couch that faced the big living room picture window. Mary had a small scrape on her left arm.

Her body could be seen through the front window lying on the floor.

Fred Hankins found her when he came home. An ambulance carried her down Broadway to St. Mary's Hospital, where she died, having never been able to tell investigators what happened.

Fred later would discover that Mary's watch was missing. He suspected the killer might have made off with it.

After the Sheriff's Office started investigating, first-term Sheriff C.W. "Buddy" Jones uttered words that would haunt him forever: "I'm not going to bed until we crack this case."

DEAD ENDS

Despite promises of hot tips and an imminent break, investigators could not close the case.

One lead pointed to a notorious daytime burglar and jewelry thief known to prowl Knoxville neighborhoods. James W. Luallen drove a dark-colored Ford. Luallen wasn't known to use violence, and investigators couldn't fully tie him to the crime.

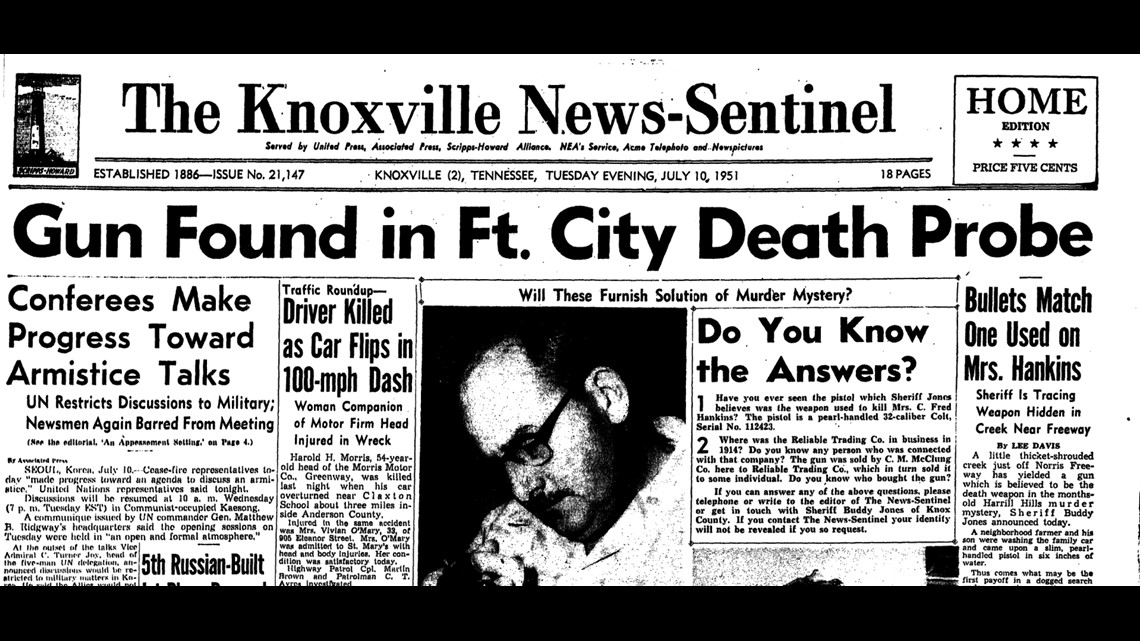

The best and maybe only significant break in the case came in June 1951, when a farmer and his son found a pearl-handled, .32-caliber pistol in a creek bed off Norris Freeway while washing their vehicle.

Sheriff Jones declared the gun's bullets matched the one that killed Hankins. A check revealed the Colt pistol was several decades old. Five bullets sat in the cylinder.

The Democrat-leaning News Sentinel broke the story on Page 1 July 11, 1951.

The Journal responded with a sniff in its own Page 1 piece. The headline read: "Hankins Murderer Free For 101 Days".

The paper said: "The brutal killing caused fear among Knox County housewives. Husbands dreaded the time when they left wives and children at home unprotected. The terror that gnawed on those who thought a mad killer was on the prowl has abated, but many in the Fountain City section are still uneasy."

Sheriff Jones was a Democrat and former warden of the infamous Brushy Mountain prison. The Journal was a staunch Republican newspaper.

Editors there had had enough of Jones. They took to calling him "Sleepless Jones," mocking his vow never to rest until someone was charged.

This was supposed to be the Sheriff's Office's case, but Knoxville police also got involved.

While Jones did what he could, Knoxville police officers conducted a parallel investigation, Speaks said. They didn't always share information, he said.

Jones put up $100 of his own money for a reward. Knoxville Mayor George Dempster offered cash for clues, as did colorful grocer and broadcaster Cas Walker.

Eighteen months after the homicide, Jones ran for re-election. His campaign carried baggage, including the Hankins case.

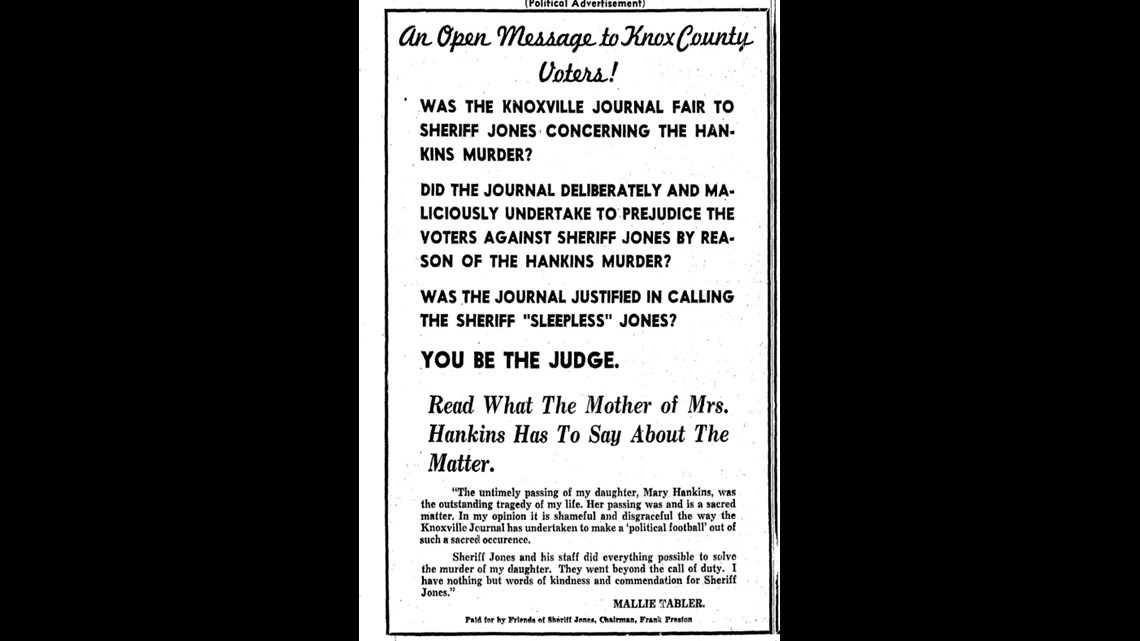

Mary's mother, Mallie Tabler, was so annoyed at the Journal that she took out an ad in the News Sentinel in August 1952. She expressed gratitude for all he'd done -- nevermind what the Journal said.

About two years after the killing, a woman came forward with the claim that she'd been with a man on the day he'd driven to the Hankins house. Authorities brought the man from South Carolina to Knox County to face questioning and prosecution.

He sat in jail for a week, insisting he knew nothing about the Hankins murder. Legendary defense attorney Ray Jenkins took on his cause, convincing a magistrate the man had a solid alibi for the day of the killing. He'd been in a North Carolina forest, Speaks wrote.

AFTERMATH

Sheriff Jones lost the election, and later moved to Florida. His successor, Republican Austin Cate, vowed to stay on the case but he, too, failed to get a conviction.

Luallen's name kept popping up as the years passed. In the mid 1960s, the News Sentinel marked his latest arrest and noted his possible tie to the Hankins case. But he died without ever being charged.

"There are two mysteries," Neely said. "One is we don't know who did it. And the other is, Why did they do it? We have no motive. Usually you have some clue about a motive. But this has no known motive."

Speaks said he hasn't tried to guess at what happened.

"I don't try to solve the problems that the police couldn't do," he said. "So I honestly don't know."

Fred Hankins, cleared by the police early in the investigation, endured enormous community scrutiny and suspicion as the potential killer.

Nearly a year after Mary died, he wrote a letter to Sheriff Jones that the Journal published in a Page 1 story.

The widower acknowledged he'd been the subject of "whisperings and rumors" about the homicide, but reminded the sheriff he'd always cooperated. He'd submitted to a "lie detector" test and been fingerprinted.

He even offered to take a "truth serum," a reference in that era to a drug such as sodium thiopental that supposedly made people more willing to spill the beans.

"...I assure you of my continued cooperation in an effort to solve this crime," he told Jones.

Hankins remarried. An avid golfer, his name and shooting score would sometimes show up in the years to come in the newspapers' small type. He was a founding member of the Beaver Brook Country Club.

Fred Hankins died in December 1999 two days shy of his 80th birthday at the same hospital where Mary perished.

His obituary stated that he'd been preceded in death by his first wife. The notice didn't mention what happened in Harrill Hills.

He was buried in Lynnhurst Cemetery in Knoxville, some 12 miles from Mary.