KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — Sometime around December 1974, a killer came to town. By the time he'd left Knoxville, he'd notched another victim.

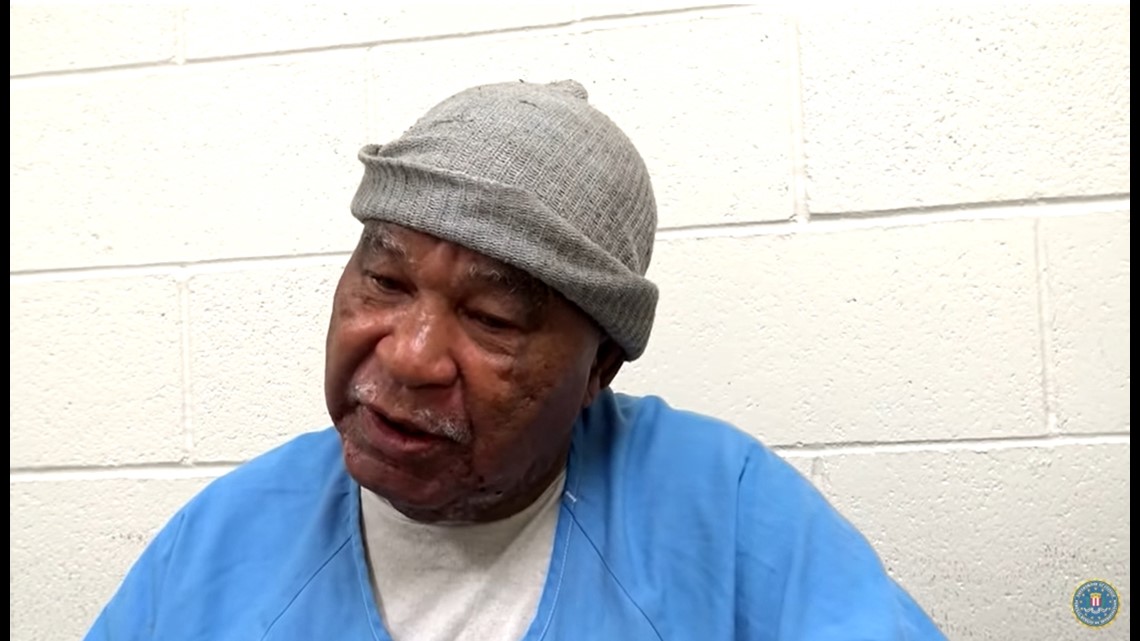

Described today by the FBI as America's most prolific serial killer, Samuel Little strangled Martha Cunningham and left her body off remote Oglesby Road in East Knox County. He likely killed her New Year's Eve 1974 or early on New Year's Day.

For more than 40 years, however, no one even thought the 34-year-old had been murdered. Dubious police work and the random nature of Little's travels meant the dead woman's case was dismissed as a likely natural death, key evidence to the contrary.

It was Little himself who shed light on the case. In 2018, he admitted killing 93 women across the country from 1970 to 2005.

Included in that spree was Cunningham, a woman of God cursed to cross paths with a serial killer.

"Everyone described him as really a nice, gentle person when you first met him. Slick, a good talker, able to talk his way out of anything. And you could tell that because he was charged with I don't know how many different crimes and he always got out of them," veteran East Tennessee criminal investigator Dave Davenport recalled.

HIS M.O.: DUMP THEM IN THE WOODS

The first sentence summarizing the doctor's external exam of Cunningham's body Jan. 18, 1975, offers a hint of the times in which her autopsy was conducted: "The body is that of a well developed, well nourished Negro female."

Hunters found her body. It appeared she'd been in a field near woods not far from Interstate 40 for at least a couple weeks. Only years later would authorities learn that Little had strangled her and abandoned her there.

As happens with any body left outside for days at a time, Cunningham's corpse had started to decompose. The January weather, however, ensured it did not happen quickly.

The body was clothed. But something was obviously not right.

"Her clothing is in disarray with stockings and panties pulled down onto her thighs exposing the pubic area," the external exam states. "Her slip and dress are pulled over the chest exposing the lower abdomen."

The report continued: "A bra is found in place under the dress."

For whatever reason, county investigators didn't think enough of the condition of her clothes to suspect foul play.

An internal exam of the body, including the vital organs, offered no clue that she'd been killed. In the opinion of the pathologist, there was no clear sign that she'd been harmed.

"No obvious cause of death was noted," the doctor wrote. "Death due to undetermined causes."

Family members reported that she had a history of seizures. And that's what county investigators ended up seizing upon as the probable circumstances that led to Cunningham's death.

A seizure. Not a homicide.

If there ever was a 1975 Sheriff's Office file on her death, it's long gone, Davenport said.

Looking at the case from the 21st century, Davenport sees reason to suspect foul play, including the fact that her genitals were exposed.

"Her jewelry was missing. How did she get out here?" he said, standing near where her body was found off Oglesby. "She didn't drive. I mean, there's a whole lot of unanswered questions. Of course, the family had unanswered questions, too."

'ALL I KNOW IS I LOST CONTROL'

The magnitude of Samuel Little's decades of death started coming into focus after DNA testing around 2012 linked him to the killings of several women in Los Angeles.

Little was born in Georgia but grew up in Lorain, Ohio, west Cleveland. He told investigators his mother worked as a prostitute, until men no longer wanted to lie with her. His grandmother raised him.

As a child, he'd later acknowledge, he developed a fascination for women's necks.

Intrigue turned to obsession. Strangulation would become his preferred method of murder, all except for one woman who he said he drowned.

Little denied for years that he'd killed anyone. But after his convictions in the deaths of the Southern California women, his stance changed.

He started talking.

In a series of interviews with a Texas Ranger who won his trust, Little began describing killings he'd committed all over the United States.

"All I know is I lost control," he would say.

After his California trial, he also spoke to writer Jillian Lauren, who talked about her phone conversations with him in the early 2010s in the 2021 true crime miniseries "Confronting a Serial Killer". Lauren has a book -- "Behold the Monster" -- about Little coming out next year.

Little preyed on the vulnerable, including drug addicts and prostitutes. Many of his victims led precarious lifestyles, the kind that often led to an early death.

They were often the kind of people who would not be missed.

"When they die they're all your favorites," he would tell his interviewers.

A drifter, he moved state to state -- from the Midwest through the South and on to the West -- often with an older girlfriend who loved to shoplift. They stayed in motels, and occasionally they got arrested for crimes that included theft.

The deaths of many of his victims first were considered overdoses or chalked up to accidents or undetermined causes.

To the surprise of Knox County investigators, Little recalled killing a local woman named "Martha," Davenport said.

A former Tennessee Bureau of Investigation agent and Jefferson County sheriff, Davenport by 2018 was working as cold case coordinator for the Knox County Sheriff's Office.

The FBI passed along what information Little could recall about Martha from 1975. It was up to Davenport to piece the rest together.

PUTTING THE CASE TOGETHER

The Sheriff's Office had no file that matched the homicide described by Little.

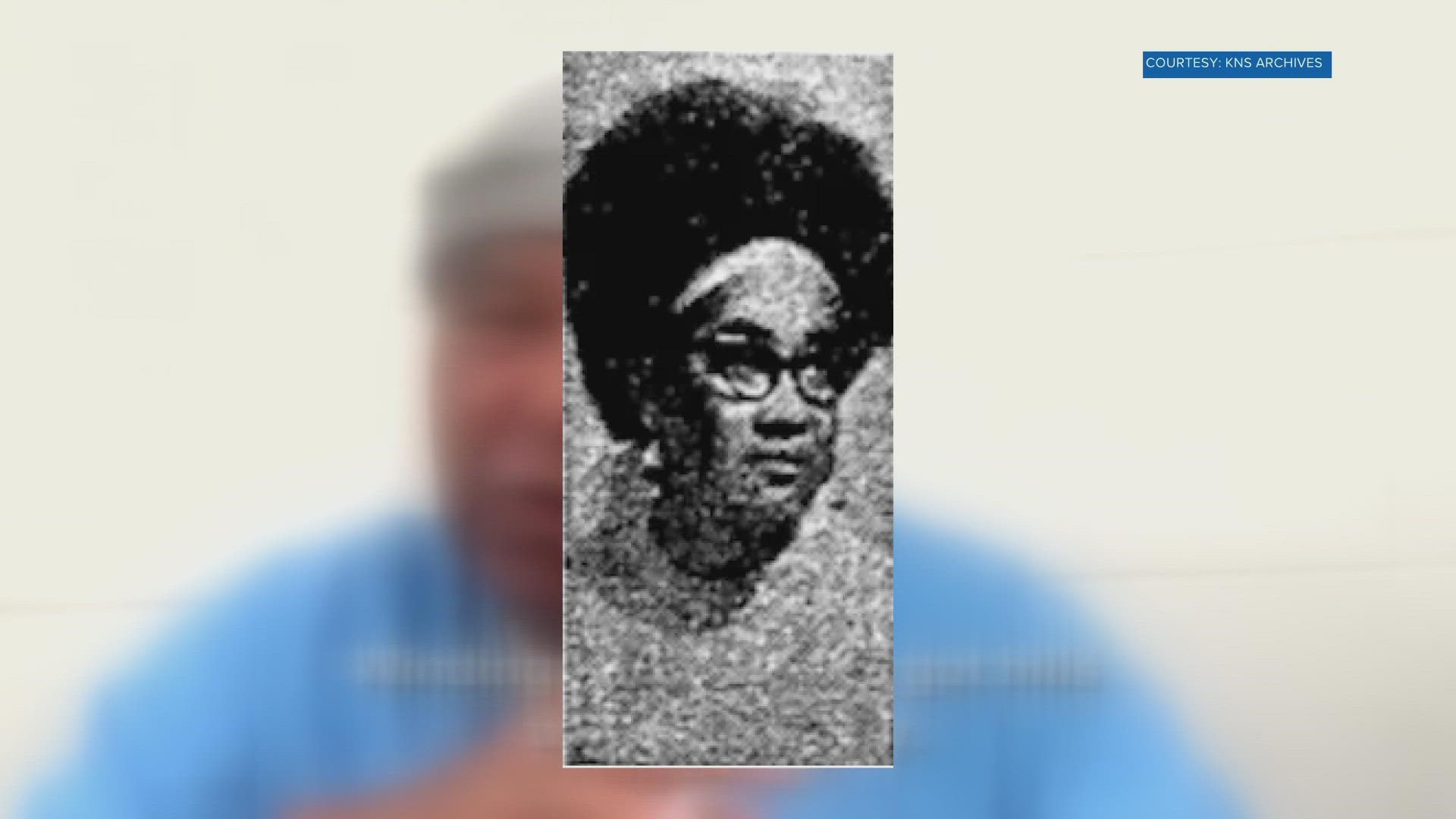

So Davenport started by hunting for newspaper articles about missing or dead women from the era. He found one Jan. 20, 1975, stuck inside the News Sentinel with the headline, "Woman's Death Appears Natural". The woman was Martha Cunningham, a lifelong Knoxvillian from a churchgoing family that once had been part of a local singing group.

Martha was not a prostitute. But it's possible she fell for Little's charm because he did have a reputation for being attractive to the ladies, Davenport said.

"I think from what he told (authorities), he had seen her on more than one occasion," Davenport recalled. "And then on New Year's Eve, he brought her out to the woods, strangled her and killed her."

He tracked down her family, who shared what they could. She'd last been heard from on New Year's Eve night 1974, he recalled. She was supposed to be at church in East Knoxville.

After that night no one ever heard from her again.

As he recalled murder after murder, Little gave investigators many clues -- details about the killings, even snatches of conversations with victims -- that helped police in places like Ohio and Florida put together unsolved cases.

He claimed to have a photographic memory that allowed him to sketch out portraits of many of his victims.

But he also was vague on some details and appears to have mixed up or confused some cases with another.

"I lost track," Little later would tell police. "I had to count by states."

Davenport is satisfied Little killed Cunningham.

"He gave us so many things that made us believe he was telling the truth," he said.

Cunningham's family said they preferred not to comment for this story. Little said he did it, they said. They don't want to revisit the painful memories.

Little also talked of killing another woman in Knoxville. But police haven't been able to match that recollection with a case, Davenport said.

According to his recollection, she was about 25 years old and 5' 5" to 5' 6". He thought he'd first met her in a Black neighborhood near or at a graveyard, perhaps around Fourth Avenue.

He recalled leaving her body in January 1975 in a gully within a half-mile of Vine Street near the "Black projects." He thought she might have been dressed in pants and a blouse.

"We never could find anything that fit that description," Davenport said.

Little also is linked to two other Tennessee killings.

He never was charged with Cunningham's killing. He died Dec. 30, 2020, in a California hospital at age 80 while serving a life sentence for the killings there.