A Legacy of Community: The History of East Knoxville

From the turn of the 20th century to the modern-day, East Knoxville's history has revealed a community of resilience, compassion, and change.

Over the years, the East Knoxville community has seen wealth and poverty, development and destruction, and prosperity and stagnation; it has all culminated in a complex history forming the foundation of the community.

Through it all, one constant — the people.

Despite every challenge, there have been people to stand up for one another. There has always been someone willing to work so East Knoxville could see better days.

Starting with the construction of Magnolia Avenue, through the turbulent years of Urban Renewal and looking forward to its future, we are looking at the history of East Knoxville and how it became what it is now.

Magnolia Avenue The road to the future

At the advent of a new century, in the late 1880s, travelers in East Tennessee would traverse boundless trees and mountains for a promise of refuge in Knoxville.

There, the city promised to dazzle them with new electric streetcars while masking the marks of a brutal civil war just a few decades earlier.

It offered jobs in the city’s 40 factories, and the railroad could take workers across the country as they continued their journey in search of labor. And in what is now East Knoxville there was a broad, grand street.

Pass through it, and residents would brush against magnolia trees.

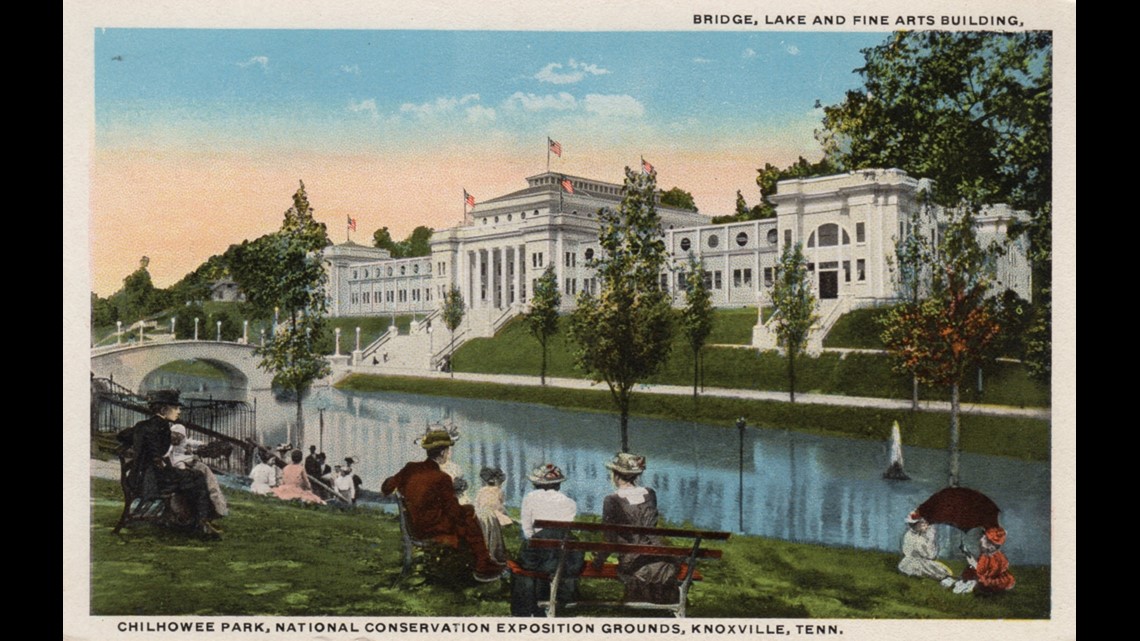

Today, Magnolia Avenue may not be the most bustling part of Knoxville, but it does not hide the prominence it holds in its past. The street was originally created to link Chilhowee Park to the downtown area.

Thousands of visitors would roll by pristine buildings and Beaman Lake like a red carpet for the city. Most visitors arrived by streetcar; the street was the first in East Tennessee with an electric car. It operated until its final run in 1947.

“That says something about what Knoxville thought about Magnolia,” said Jack Neely, who works with the Knoxville History Project.

Nearby, past the magnolia trees, there was swimming, dancing, outdoor escapes and even horse racing. Deceivingly, the street did not get its name from the landscaping. Instead, it was named after a woman — Magnolia Branner.

Chilhowee Park A sight to see

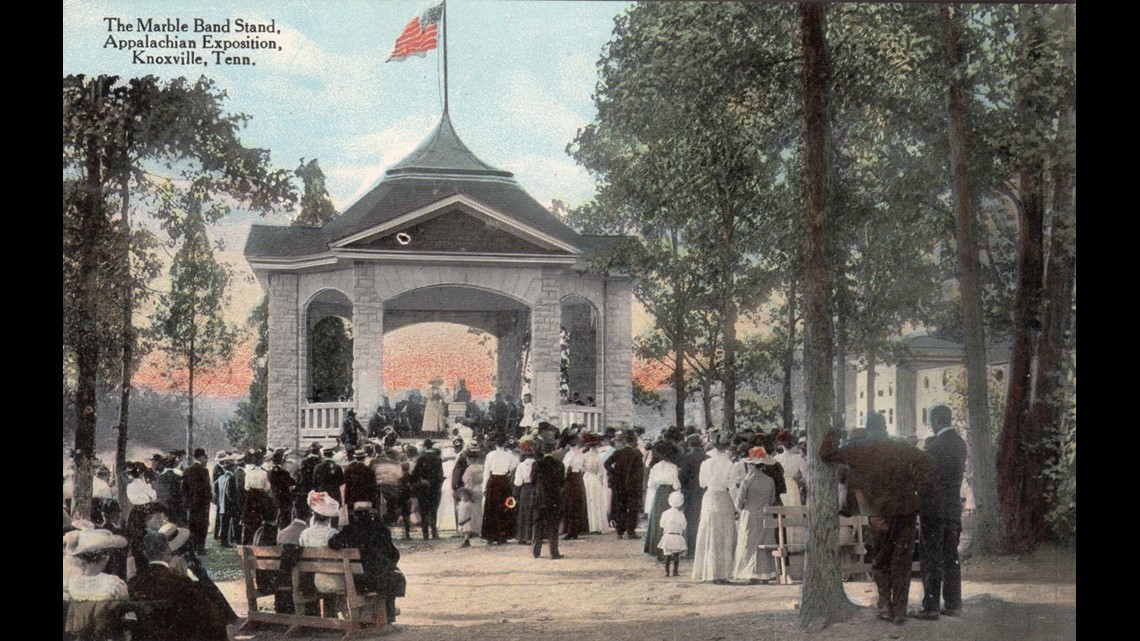

Branner was the first one to call the road her home. In 1907, she would pass away. It was just a few years before Chilhowee Park became a national attraction due to the Appalachian Exhibitions.

“One million people from around the country came to Chilhowee Park over a period of two months to see this amazing exhibition,” said Neely.

The National Conservation Exhibition arrived at the park in 1913, which included a pavilion dedicated to African Americans. In the years after the Civil War and into the turn of the 20th century, Knoxville would not adopt as strict segregationist policies as other cities.

However, people were far from united despite people of all backgrounds traveling the same road.

The Tennessee Valley Fair opened in 1916, and it evolved into a major event for the community. It brought almost everyone out, giving everyone a second chance for fun in the park if they missed the 1913 exhibitions. Only the bandstand survives today, along with some of the businesses it helped form.

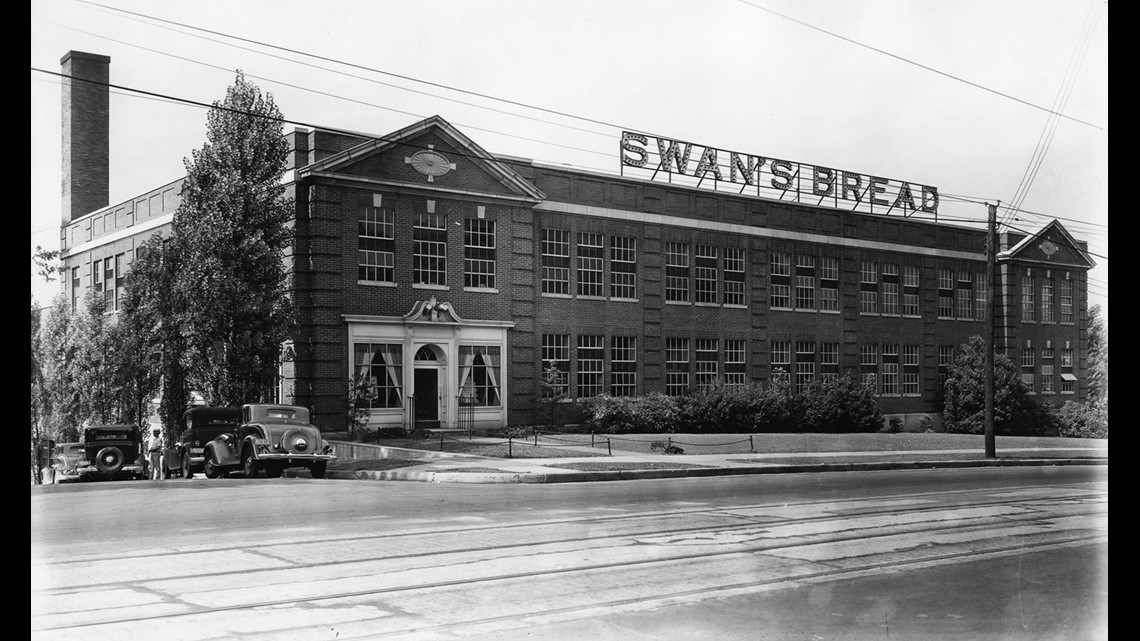

As crowds gathered for the fair entrepreneurs saw their chance to make money and set up a market on Magnolia. One of them was Swan’s Bakery with a state-of-the-art factory opening in 1927.

Years passed by like streetcars, fairs continued and businesses grew along Magnolia Avenue. Park Theatre opened in 1938, helping create the first generation of movie-goers. In the 1940s, the road gave the world a taste of something new — Mountain Dew. The drink first fizzed out of the original Hartman Beverage Building on Magnolia Avenue.

Despite all the changes through the decades, Chilhowee Park continued to be the main attraction.

“I started going maybe when I was 7 or 8 years old,” said Robert Booker, Knoxville's first Black representative in the Tennessee Legislature. “And, during that period, Black people were only welcome to Chilhowee Park one day per year.”

The Segregation Era The community faces new division

The Segregation Era had begun, literally dividing Knoxville. In 1948, the city council began allowing Black patrons in Chilhowee Park once per week. Back then, it was touted as a major advance toward social equality.

“We could only go to the park on Thursdays for the skating rink,” said former Mayor of Knoxville Mayor Daniel Brown.

Around the same time, something new accompanied the old trees on Magnolia Avenue. It was louder than factories, sweeter than Mountain Dew and flashier than the movies. It was rock ‘n roll.

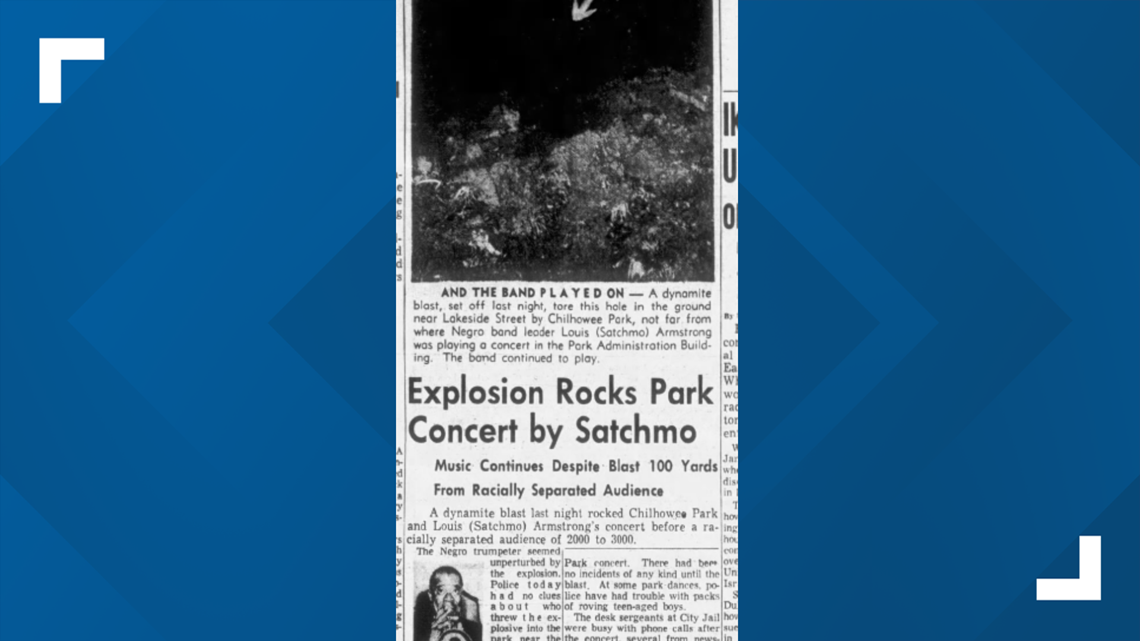

The Jacobs Building opened as a performance hall in the 1940s, and soon Chilhowee Park became a spot for big shows in the mountains. There, Knoxville welcomed big-name Black artists like Duke Ellington to James Brown.

Audiences gathered for their shows, but they did not gather together. They were segregated with white people sitting on the balcony while Black people danced on the main floor.

During one performance by Louis Armstrong, a dynamite bomb went off outside the building. His smooth grooves were mirrored only by his smooth personality though.

“Louis Armstrong said, ‘Don’t worry, folks. It’s just the telephone,’ and he went on with the whole concert,” said Neely.

Eventually, the park opened to all people in 1961, whenever they wanted to visit. Yet, life on Magnolia Avenue remained segregated. Black people were not allowed in restaurants by the trees, and the first fast-food company there refused to sell to Black customers.

Yet, the road was a hub for food and entertainment as time passed by. As the magnolia tree blossomed, wilted and blossomed again, the people of Magnolia Avenue came and left.

Knoxville later expanded as the 20th century came to a close and residents left Magnolia Avenue behind with all its glamor and extravagance. The road has seen horses, streetcars, Fords pass through while people walked on into the nearby city.

Through all that time, one thing has stayed the same — more than 100 magnolia trees still stand along the road, decorating the road as it decorated Knoxville’s history.

Austin-East Magnet High School A Mind is a Terrible Thing to Waste

It’s a long road to Austin High School in the 1950s and 60s, but like the saying engraved in stone towards the entrance of the school today — a mind is a terrible thing to waste.

Students walk with their books in hand, buses passing by with close friends and siblings at their side for a chance at the most fundamental part of any American dream — an education.

Although the lessons scratched on chalkboards may have been the same, students in East Knoxville spent many years divided. They went home with different lessons at the end of the day, depending on the color of their skin. Some learned their lives would be more difficult than others.

During the Civil Rights Era, classmates knew each other well and watched out for each other. It was a side-effect of segregationist policies in Knoxville.

Despite the time spent divided and unequal, Austin High School started with a woman’s dream to bring high-quality education to the area’s Black community, just a decade and a half after the Civil War.

Austin East's Beginnings It started with a dream

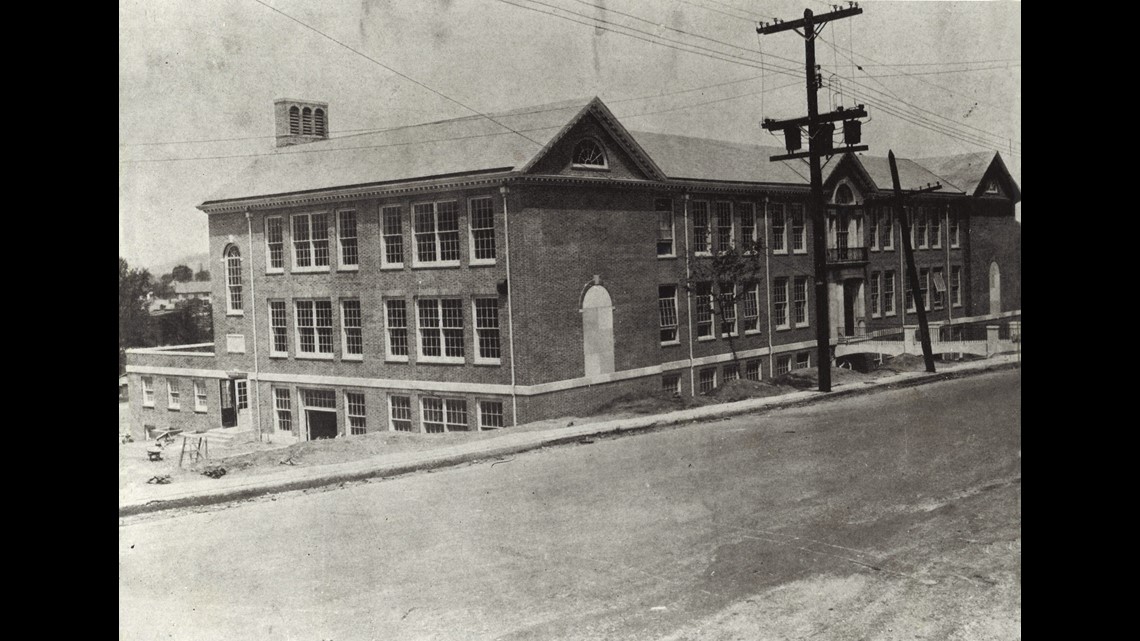

In 1879, she raised funds and convinced the Board of Education to contribute to the creation of the school. That same year, she opened the first public high school for Black students in Knoxville. It was located at 327 South Central and was there until 1916.

The school moved locations from Payne Avenue to Vine Street several times over the years, but the community moved with it.

“It was a very good school — had some very excellent teachers,” said former Mayor Brown. “And, at that time because of segregation, you had a lot of your teachers living in the area, or you went to church with them. So, you knew them, and they knew you and knew your family. So that made a difference.”

Students and staff alike got to know each other, developing a sense of comradery and commitment to learning. Eventually, in the fall of 1952, the school opened a new campus.

Meanwhile, in 1951, white students from Park City, Burlington and other East Knoxville neighborhoods started classes at East High. They became the Mountaineers.

East High and Austin High School were two of several new high schools in the city’s school system. With an economic boost after World War II and money flowing freely in the U.S., Knoxville leaders decided to invest in the city’s education.

“Most of us were blue-collar,” said Sam Furrow, who started attending East High in 1955. “You knew very few people who owned their own business. It was a very, very strong blending environment. We had Jewish kids, we had Greek kids.”

Yet, there were no Black students at East High School.

Even though a Knoxville judge would bring integration to students in Clinton, progress would be slow in Knoxville itself. For several years, students learned in different buildings because of racial differences. Many were taught segregation was just the way things were.

“I had no experience with any kind of integration the rest of my time in public school because they fought it,” said former Mayor Brown.

Desegregation at Austin-East Students start learning new lessons

During the mid-1960s, leaders worked to desegregate the city’s schools and especially East High School. In 1968, Austin High School and East High School became one, taking one more step towards becoming the school the city knows now. For many years, it was known as ‘Austin-East High School.’

The policies hadn’t entirely stopped segregation though, and in the years after the creation of Austin-East High School, it became virtually all Black as white students left, according to Robert Booker. Once again, leaders tried to bring students together to get the same, equal education. They created a magnet program to attract a diverse school community.

With the creation of that program, Austin-East Magnet High School was formed.

Time and time again, the school stayed committed to the promise given to its first students. It would always offer them a chance at an education, to brighten their futures and to succeed.

Throughout its history, Austin-East Magnet High School followed the course started by the idea engraved at its entrance — “a mind is a terrible thing to waste.”

Urban Renewal Brings Change and Destruction East Knoxville faces demolition

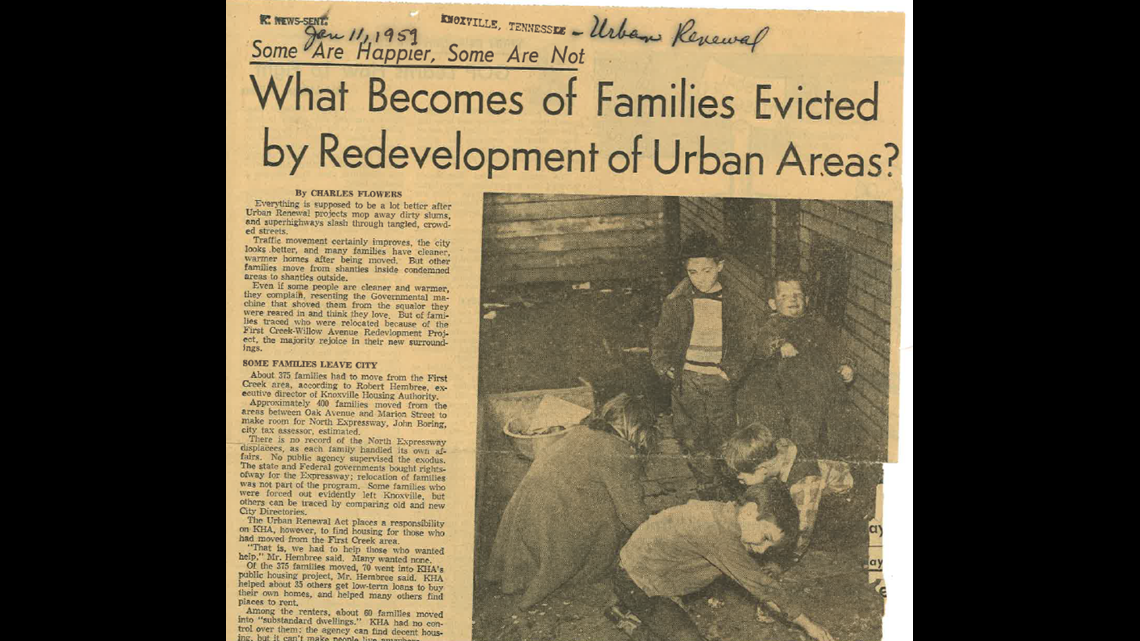

Cities change over time. They develop, growing and thriving as they build farther into the space around them. Knoxville’s Urban Renewal programs were no different — another opportunity to fill the air with construction noise and build a brighter future for the city.

Change can come at a cost. For many communities in Knoxville, urban renewal programs lost them their homes, their safety and their future. In December, the Knoxville City Council passed a resolution apologizing for urban renewal policies.

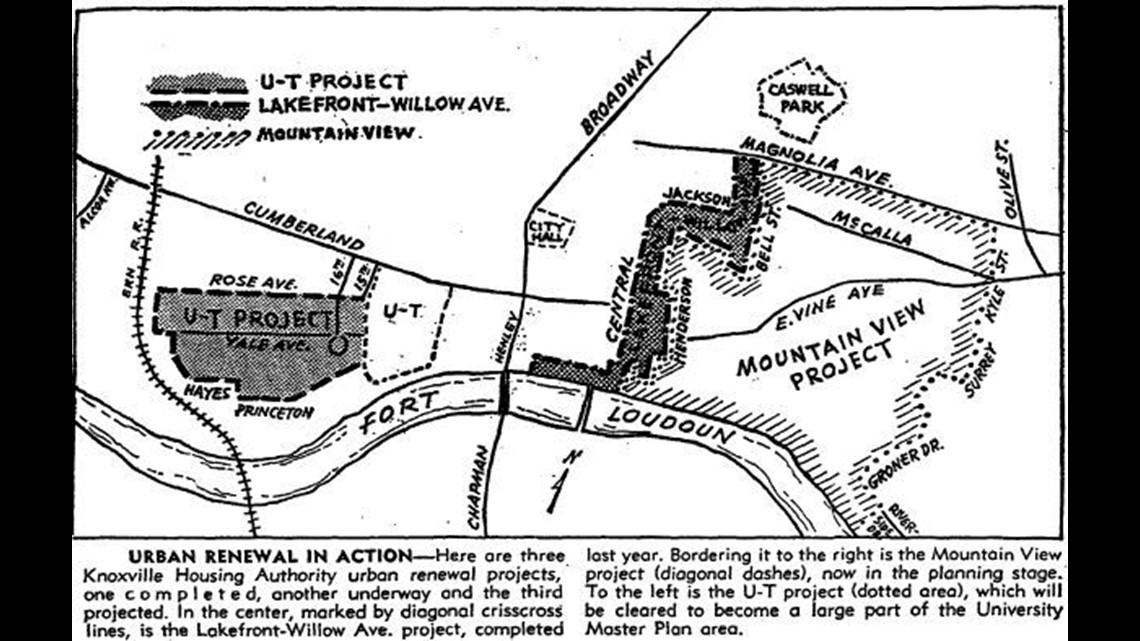

As the University of Tennessee and downtown areas grew, taking advantage of the new developments, historians say they also pushed the communities in East downtown Knoxville away, all in the name of progress.

For many communities, urban renewal programs left Knoxville with more than just a new highway. They left a legacy of displacement, abandonment and poverty among the city’s communities of color.

Urban Renewal's Devastating Impact Promises of a bright future turn sour

The turn of the 20th century promised change across America — a brighter future filled with new technology, affluence and social rejuvenation.

The early 1930s brought the most severe economic downturn the country had ever seen. The Great Depression left people in desperate conditions, struggling to afford necessities.

Even though it ended in 1933, homes in Knoxville were still in destitute conditions by the 40s with flooding creeks routinely pouring into “The Bottom,” an East Knoxville community named for its low-lying topography.

"In that neighborhood were many hard-working people, poor people who lived below the poverty line," said Robert Booker, who grew up in The Bottom. "Every Spring, the creek would rise either because of heavy rains or melting snows. Many of the houses in that areas were substandard, so we just had to rough it in The Bottom."

Several homes did not have electricity or plumbing. Yet, the area had more than just crumbling homes and rising waters.

The KUB building ran the city’s public infrastructure from Jackson Avenue. Workers milled through the area, living in homes where they raised families. Until the early 1960s, most of the community included Black-owned businesses.

“People living there just got used to the idea of hearing water under their floorboards,” said Jack Neely, a Knoxville historian. “There were still people living in literally third-world conditions.”

Federal leaders wanted to change this as they underwent an effort to strengthen communities across the country. They started a federal urban renewal program, providing grants for cities that undertook projects to build interstate highways, public housing and removed condemned structures.

At first, residents of The Bottom welcomed these improvements during the 1950s. For many families, it meant having electricity for the first time and easy access to the new national highway system. Knoxville also had the chance to build the Civic Coliseum as part of the project.

During this time, families would be uprooted from their homes and lives. They would never have the chance to enjoy the improvements made in their former communities. For many people in Knoxville, Urban Renewal came at the cost of their place in Knoxville’s bright future.

"We knew those structures needed to go," said Booker. "We knew that creek needed to be corralled. And there were other things that required Urban Renewal, but unfortunately, Urban Renewal went too far."

The Cost of Change "We're tearing down way too much"

Nearly 3,000 structures were demolished during Urban Renewal in Knoxville, including the African American Carnegie Library, the Black Medical Arts Building and the Gem Theater.

“By the late 60s, you start seeing people saying, ‘Wait a second, we’re tearing down way too much,” said Neely.

Former Mayor Daniel Brown also saw his home and community demolished during the program. His church was torn down, the home was born and grew up in was destroyed. He was also far from alone in this situation.

Urban Renewal programs uprooted 2,500 families, and 70% of them were Black. The city used eminent domain laws to demolish their houses, paying market value for their homes. Since The Bottom was so underserved that the market value did not equate to the cost of finding a new place to live in the city.

“They didn’t have a place that they could move into,” said Neely.

Families living in private homes, before Urban Renewal programs upended their lives, ended up moving into public housing since many were unable to afford new homes of their own. The program also led to increased segregation in the city, with new developments specifically for Black families and white families.

“They built Austin homes and college homes for Black people, and they built Western Heights for white people,” said former lawmaker Booker.

Most families that moved into public housing had their first experiences with plumbing and electricity, after being forced from The Bottom. Many would stay there for a generation, unable to secure equity and real estate for their children. As Urban Renewal continued, the community changed.

Many families had to leave their churches, one of their main connections to friends, and Black people were pushed farther into East Knoxville.

“So, after 1963, East Knoxville basically became a Black community,” said former state representative Booker.

East Knoxville Finds a New Future The community picks up the pieces

Eventually, leaders built the eastern loop of James White Parkway. It put a physical divide between the East Knoxville community and the downtown area, and families started to adjust to their new lives.

Former Knoxville Mayor Brown moved to the Burlington neighborhood off Magnolia Avenue after his original home was demolished. As he grew up into a lawmaker, he watched the property around his original house stay empty. Nothing was ever built to replace it.

“All you have now is just a park,” he said. “It’s nice, but it doesn’t make sense to tear down houses to build a park.”

A few businesses survived the years of demolition and upheaval. Jarnigan and Son Mortuary is a Black-owned business that survived after moving to its current location on Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue in 1969.

However, the majority of businesses were scattered into different locations, losing their customer. Meanwhile, the University of Tennessee and Downtown Knoxville areas had a chance to expand into white, affluent areas.

Despite the years spent cultivating a community in East Knoxville, many landmarks that demonstrated the history and beliefs of Black families are gone too.

“They don’t exist because they’re gone,” said former Mayor Brown. “Nobody thought about preserving a lot of the things that are historical to the Black community.”

In the span of a few years, Knoxville built new structures and enhanced the city. For many families, it came at the cost of their community. With wrecking balls and bulldozers, parts of the Black community’s history in Knoxville were destroyed — replaced with Urban Renewal and sacrificed for progress.

Leroy Thompson Thompson's 'hail mary' move

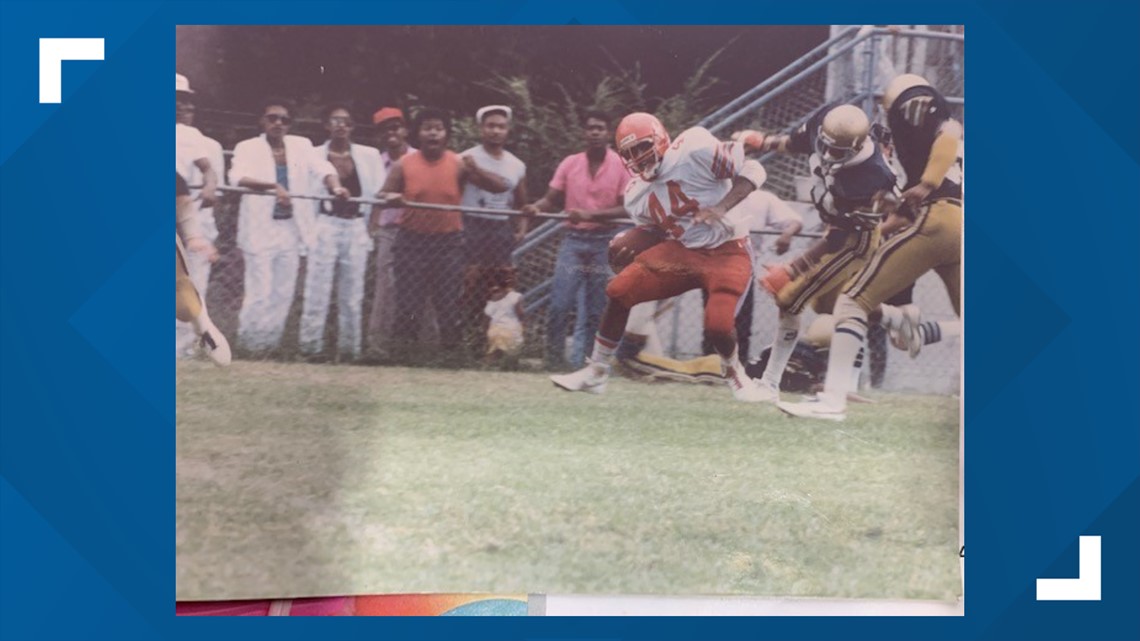

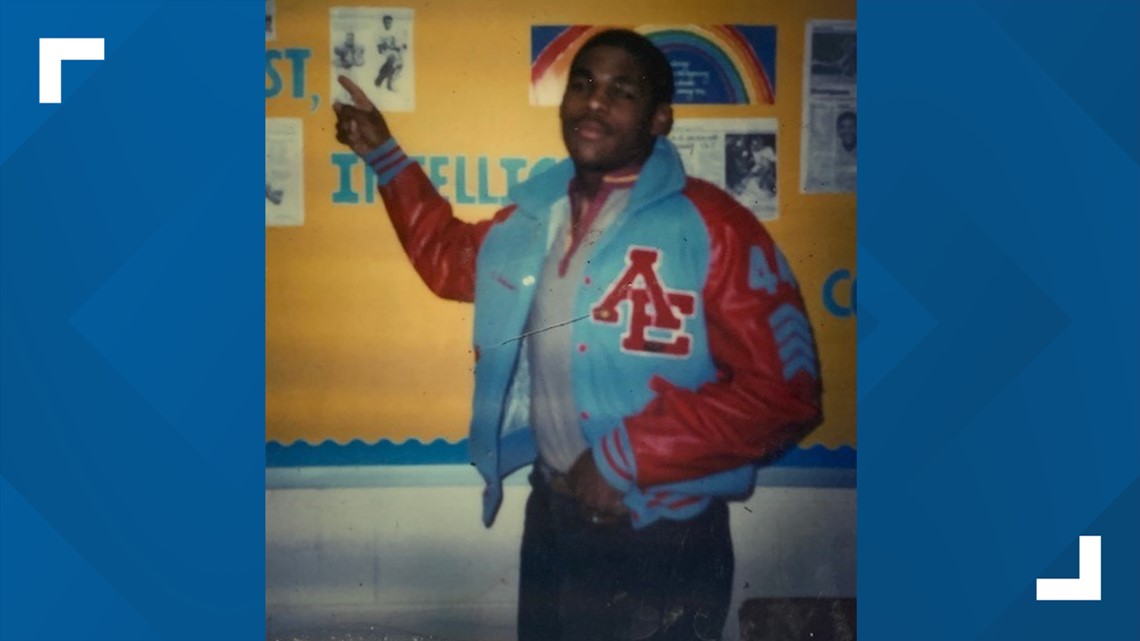

Sometimes, the people who make the biggest impacts also have the smallest beginnings. Leroy Thompson is one of those people, who made his way into the NFL after growing up in East Knoxville.

“They used to have a joke saying when the rent was due, we moved,” he said. “I always say we may have been low-income, but we weren’t low-class.”

He lived in places throughout the East Knoxville community, from Austin Homes to the Burlington Neighborhood. He said it was never easy growing up with a lack of resources, but he had people on his side to help him succeed. They taught him how to dream beyond his circumstances, and how to reach for the stars, staying away from crime and violence.

“We were busy with summer jobs, we were busy in sports and it was purposely done,” he said. “We were purposely kept busy so we wouldn’t be attracted to the negative elements in the community.”

Eventually, he became a star after thriving in athletics. While attending Austin-East High school, he helped The Roadrunners win a state basketball title in 1985 and then a state football title in 1986. Back then, the school was only a quarter the size it is now. Despite his high school’s small size, he collected offers from 125 colleges to play football.

They filled a small apartment he was living in at the time, where recruiters also sat down to convince Thompson he should play football with them. They were called the Prince Hall Apartments, he said.

“It’s where Joe Pattern came to recruit me, Jimmy Johnson, Vince Dooley — all of those guys were sitting in that little brick apartment when I was coming out of Austin-East school,” he said. “I didn’t necessarily dream of playing in the NFL, but I did dream I could play in college — big-time college.”

He didn’t just want to play football in college. Thompson also said he wanted to travel since he had never had the chance to. At the time, he said he had never been past Nashville to play in a state championship game.

He went to Penn State, but he could never leave East Knoxville. Thompson said he returned every year to invest in community organizations, supporting the people who had his back.

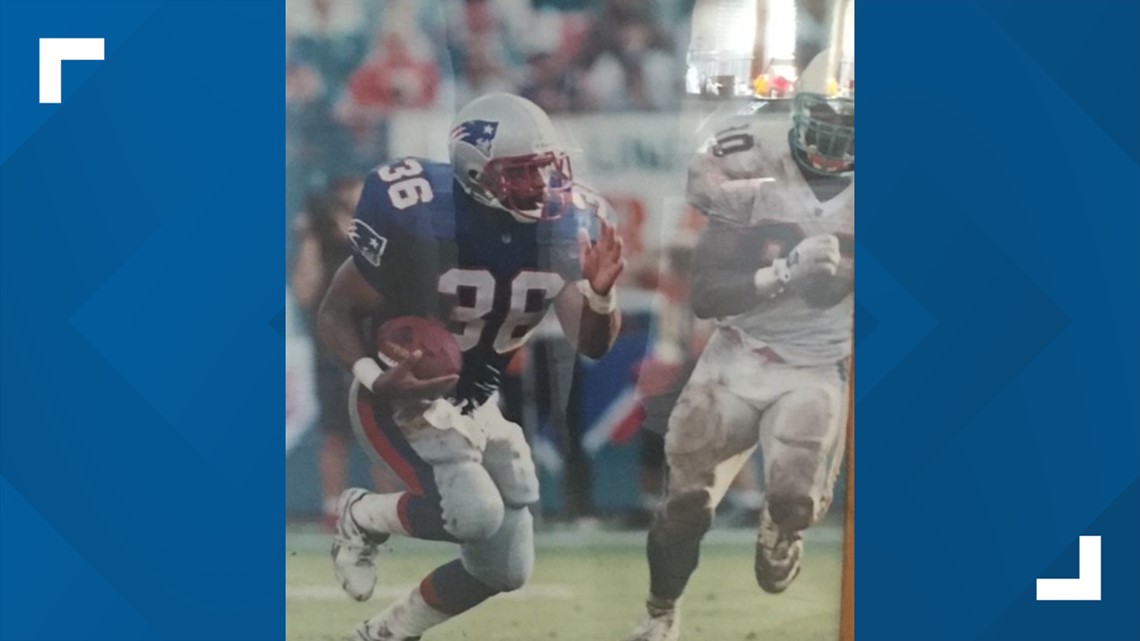

Then, in 1991, Thompson was drafted by the Steelers. The announcement came with a big paycheck, which he used to pay back the person who supported him the most — his mother.

“The first thing I did was buy my mom a house,” he said. “I wanted to buy my mom a house in Holston Heights.”

Thompson's Return Giving back as quickly as possible

The support he gave the community counted. While he was away, its economy would take hit after hit. First, Standard Knitting Mill closed. As a result, crowds of people were left without a job in 1989. Nearly a decade later, Levi Strauss also shut down in the area, terminating an additional 2,000 jobs.

“It had a major effect on the community because those were jobs where people could earn a decent living,” said former Mayor Daniel Brown.

Later, crime filtered into the East Knoxville community. Drugs started flowing in as people lost their jobs and resources dwindled. As a result, people who had the ability to move into other areas did so, leaving the community behind.

Thompson continued providing for his community. He created his "Team Dream" Foundation while playing in the NFL. It worked with youth in the community to veer them away from drugs and gangs.

Then, when his career in the NFL ended and he hung up his jersey, Thompson returned home to East Knoxville. He wanted to help the city that helped him so many times.

He was part of an effort to develop the Five Points Villas Plaza in 2002, now known as the James Davis Plaza. It helped spark economic development in East Knoxville. Inside it was a grocery store, a clothing shop and other retailers.

One of his biggest impacts on the community was the creation of Cherokee Health Systems. He helped bring the medical organization to Mechanicsville and now it provides healthcare services to East Knoxville through a satellite office off Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue.

“It was a collective vision that came out of the partnership, a neighborhood improvement from the city and the community working together,” he said. “We have the ability over the next 3, 5, or 10 years to totally revamp and revitalize the community.”

To him, it’s a personal responsibility to revitalize East Knoxville. He said he is considering reestablishing his Team Dream Foundation as the community continues to reel from the deaths of several teens due to gun violence. He is meeting with leaders to address community challenges.

“I got to get back busy like I was in the 90s and early 2000s,” he said. “I believe that to whom much has been given, much is required. So long as I’m actively breathing, I will be looking for opportunities to bless.”

Looking to the Future

Today, the East Knoxville community looks different. Leaders are developing new approaches to thwart bloodshed, attempting to interrupt cycles of violence before they continue and hurt people.

This comes after five teens with connections to Austin-East Magnet High School lost their lives due to gun violence. One was Anthony Thompson Jr. who died in a police shooting inside the school.

Whenever the East Knoxville community faces tragedy, it comes closer together. In the days and weeks following the shooting, activists and community leaders have hosted rallies and events. They have given food to the needy, helped vaccinate people and organized for action.

The Bottom, a creative and cultural space for the Black community named after the neighborhood destroyed by Urban Renewal, is in the process of moving to Magnolia Avenue.

"We saw changes in our neighborhood that were happening quickly, that were drastic," said Dr. Enkeshi El-Amin, the founder of The Bottom. "And so, we thought it was best for us to own our space."

Former gang members also started a program to directly connect with at-risk youth, steering them away from violence. The Safe Haven program is meant to show youth that they are surrounded by a compassionate and caring community that understands their struggles.

Through the program, the founders said they hope to show kids and gang members alternatives to violence. They said that most of the time, youth turn due to a lack of resources and trouble with their family. Safe Haven is meant to show them that no matter the challenges they face, they are not alone.

Meanwhile, another group was formed to take action against violence in the community — "Protect Our People Tennessee." It's made up of fathers and community members who arrive at Austin-East Magnet High School to oversee as students board buses and leave.

The group's members say they're not just there to keep kids safe. By showing up, they hope to show youth that there are people watching over them. They are surrounded by people who care.

They also plan to host hunting and fishing trips to connect with at-risk youth directly. An Inner City Youth Summer Paintball League is always in the works, which founders hope will provide a platform to teach children gun safety. It may also help youth confront their fears through role-play while teaching them how to act in the face of danger, according to the group.

In times of strife, East Knoxville has stood strong. As city leaders invest in programs to stop violence and help the next generation thrive, the future can be a little brighter for the community knowing that throughout its legacy, people have been able to count on it.

"We have the ability over the next 3, 5, 10 years to totally revamp and revitalize the community," said Thompson.

Several resources are also available for anyone who wants to see the development and demolition of communities like East Knoxville. Maps are available from the University of Tennessee, as well as the Tennessee State Library and Archives.