NIOTA, Tenn. — If you found yourself traveling through the small town of Niota, Tennessee, you could drive right by a women's suffrage landmark and miss it.

Tucked far off East Farrell Street and practically hidden by the lush trees lining the gravel drive sits the Hathburn House, now known as the Rutledge Estate.

While its bright red roof and stark white columns on the front porch stand out against the sprawling farmland around it, this brown brick home bore witness to a pivotal moment in the fight to secure voting rights for women.

It was once the family home of Tennessee State Representative Harry T. Burn and his mother, Febb Burn.

"It’s safe to say that Harry was a mama’s boy," said Tyler Boyd, Harry's great-grandnephew. "Harry and the rest of the children, but Harry especially, deferred to their mother as the matriarch."

Febb was college-educated, had a background as a teacher and took over managing the family's 120-acre farm after her husband, James, died.

"His mother encouraged his early interest in politics. He kept up with the news and international politics, and he was well-read just like her," Boyd said.

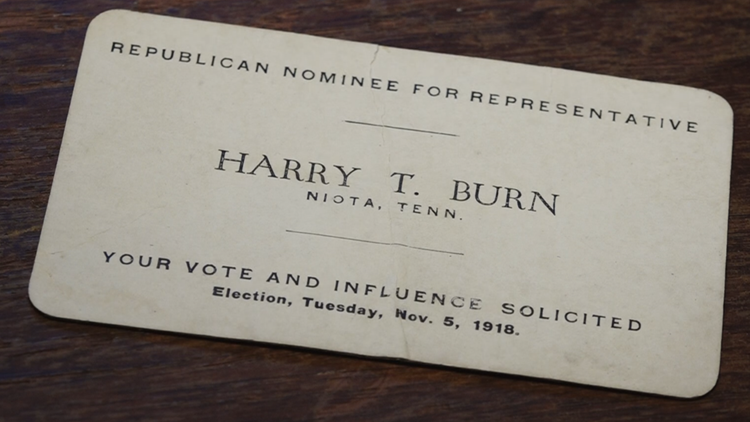

Harry was elected as a Tennessee State Representative when he was 22 years old. Little did he know that nearly two years later, he would face a decision that would alter American history: the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

The U.S. Congress proposed the 19th Amendment to the states in 1919, and 35 states ratified it within roughly 9 months. Then the amendment completely stalled. It needed 36 states to be added to the Constitution.

"The Deep South wasn’t going to go for this. There were some New England states that were kind of on the fence so it all came down to Tennessee in August 1920 when they had their special session in Nashville," Boyd said.

Harry, now 24, was staring down a landmark vote for ratification and his potential re-election.

Initially, he followed his constituents and moved to table the vote until the next legislative session. The vote was deadlocked at 48-48.

Boyd said telegrams from these constituents show attempts to mislead Harry into believing Niota was against suffrage when the historical record shows the town was actually split down the middle.

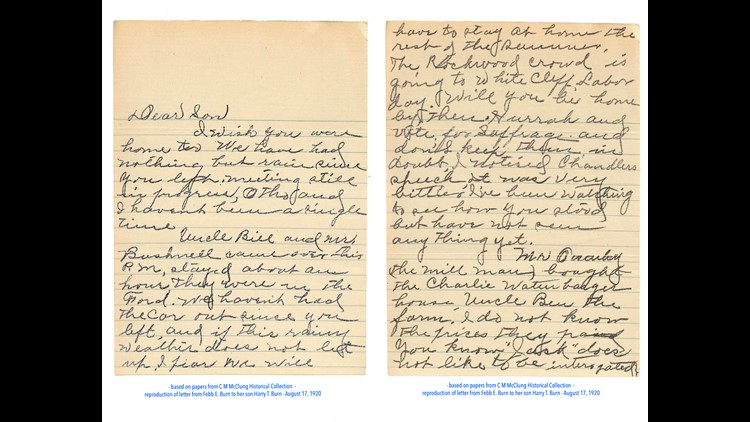

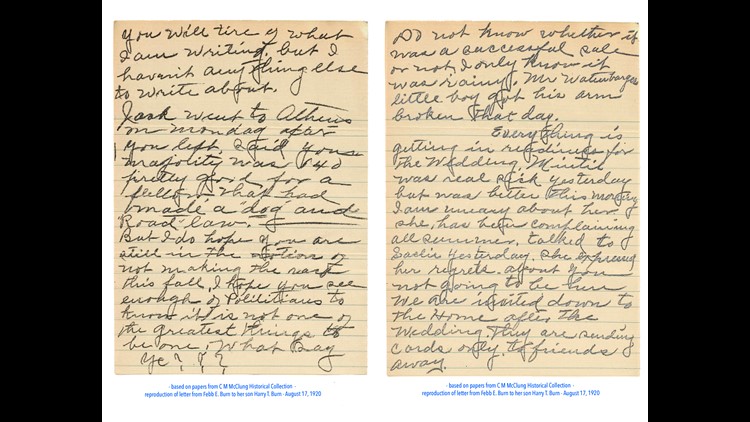

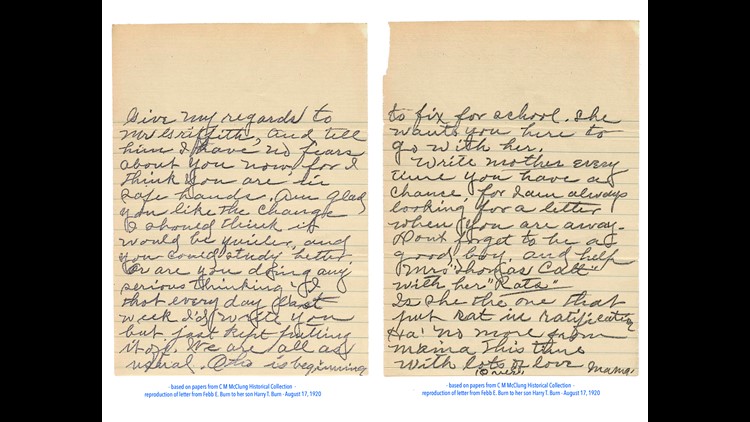

Then, just before the final vote, he received a letter from his mother, Febb.

Boyd said Febb had read some particularly distasteful speeches in the newspaper and took a break from her farmwork to sit on the front porch of Hathburn House and write to her son.

"She was the manager of the farm. She managed it successfully yet she didn’t own it. She paid the taxes but she couldn’t vote. The men working for her, a lot of them couldn’t even read, but they could vote. She didn’t think that was right," Boyd said.

In the 6-page letter, she gave Harry updates from home and advised him to “be a good boy and help Mrs. [Carrie Chapman] Catt put the ‘rat’ in ratification.”

Photos: Febb Burn's letter asking her son to vote for women's suffrage, 19th Amendment

Febb's letter can be accessed through the Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection's Digital Archive.

Back in the house chamber after reading his mother's words, Harry knew what he needed to do. As the representatives voted, it seemed the decision would remain deadlocked until it was Harry's turn.

The 24-year-old from Niota changed his vote from "No" to "Aye."

With that, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment and grant women the right to vote.

“I believe in suffrage as a right; I believe we had a moral and legal right to ratify. I know that a mother’s advice is always safest for her boy to follow, and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification," Harry said in a statement that he presented to the House the following day after being accused of bribery and coercion.

Of course, changing his vote and giving his mother her due credit in his decision stirred up a brief bout of drama.

In one instance, the wife of a former Louisiana governor who was a staunch anti-suffragist came to Hathburn House saying the letter was fake, telling Febb to disown her son and demanding that Harry change his vote again.

Febb, of course, stood by her son, said no and encouraged Harry to continue his support of women's suffrage.

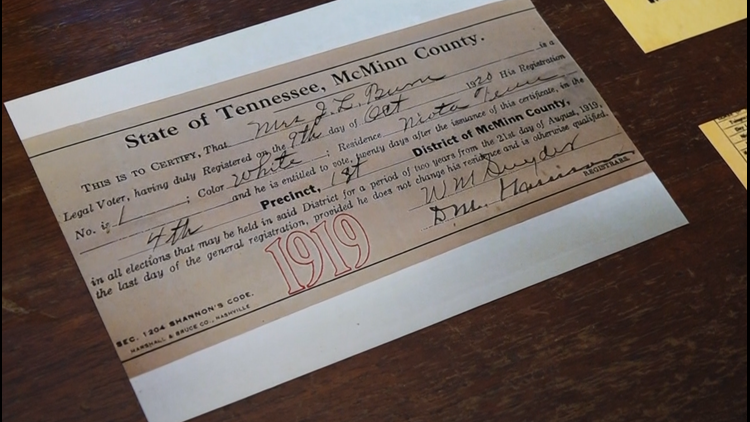

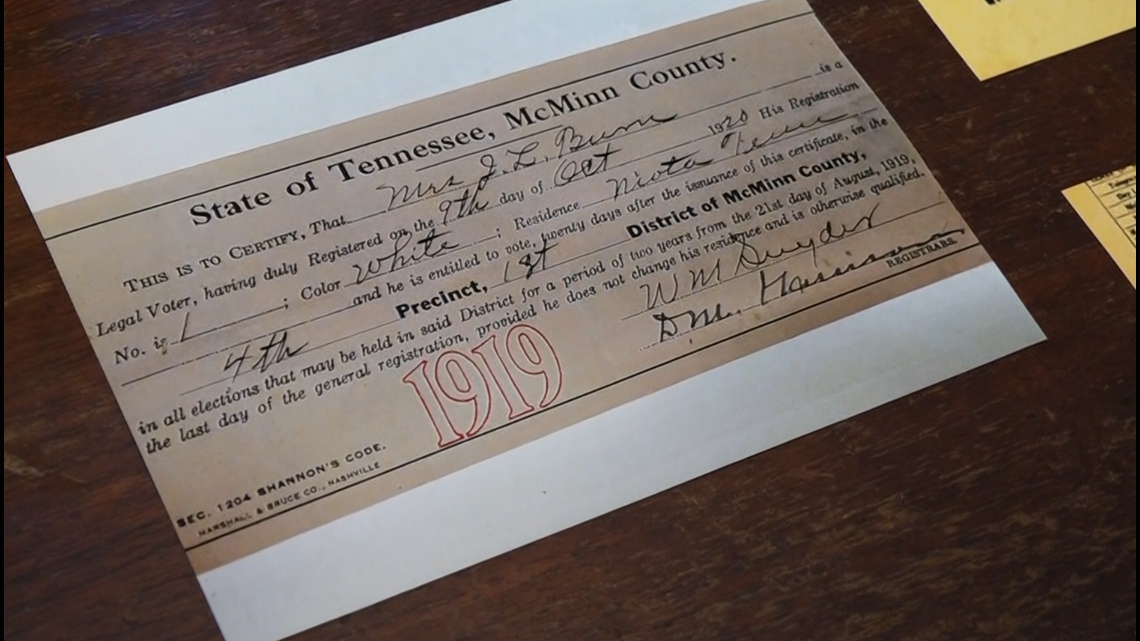

Later on in 1920, Febb Burn registered to vote for the first time ever and received voter card no. 1 in the county, which still had solely male pronouns printed on it.

Now, 100 years later, the Burn's ancestors want to make sure their legacy stays alive.

They work to encourage people to be informed and active in local, state and federal elections.

"One voice can make a difference. Febb’s voice made a difference and Harry’s voice made a difference," said Sandra Boyd, Tyler's mom and Febb's great-granddaughter.

Tyler wants people to remember that it doesn't take a storied name or certain education level to have an impact.

"The 19th Amendment wasn’t something that was ratified by a bunch of big-name people that everyone recognizes in history books. It was ratified by the work of ordinary people," he said. "Harry didn’t have a college degree. Harry got his high school diploma and went to work for the railroad. If he can do it, anyone can."

Hathburn House, now known as the Rutledge Estate, still stands as a silent symbol of the mother and son from a small town in East Tennessee who used their voices to ensure millions in generations to come would get to do the same.

"These bricks witnessed her write that letter because she took a break from her farmwork after she read some offensive speeches in the newspapers and was inspired to write her son a letter asking him to vote for suffrage. It all happened right here at this house," Tyler said.

Febb Burn's great-granddaughter, Sandra Boyd, reads her famous letter:

To help people learn more about Harry and Febb's story, Tyler wrote a book called "Tennessee Statesman Harry T. Burn" that is available now.

The Calvin M. McClung History Collection at the Knox County Public Library also has a digital women's suffrage collection where you can see Febb's letter and several telegrams sent to Harry among other artifacts from local suffragists.