Hidden Tennessee History: TN man wanted to free the slaves. He also had owned them

From his Washington County, Tenn., hometown, Elihu Embree financed and published the first newspaper in the world dedicated to ending slavery. The year was 1820.

Northerners get much of the credit for pushing to abolish slavery in the United States.

But it was an East Tennessean, four decades before the Civil War, who took the extraordinary step of publishing the first newspaper in the world dedicated to ending the slave trade.

"It is something paradoxical that a man should refuse to buy a stolen sheep, or to eat a piece of one that is stolen, and should not have the same scruples respecting a stolen man," Jonesborough's Elihu Embree declared in his self-financed "The Emancipator" newspaper in 1820.

It's also paradoxical, to quote the publishing pioneer, that he should be the one to seek an end to slavery because Embree, 38, held owned slaves himself in Washington County, Tennessee. In fact, it was his wish in death that one of his slaves and her five children finally get their freedom.

Embree's life is the story of a man of some means determined in his day to right a wrong. But he was also a man who wrestled with his own internal and material conflicts.

"I think it just speaks to how deeply complicated the history and issue of slavery was," said historian Anne Mason, executive director of the Heritage Alliance of Northeast Tennessee and Southwest Virginia, who has studied Embree's life.

Two hundred years later, many have forgotten his deeds. Indeed, no one can say for certain just where Embree's remains now rest.

History is rarely simple or etched in black and white.

Businessman, Slaveholder

Embree's family, led by pastor Thomas Embree, moved to East Tennessee in the late 1700s when Embree, born in 1782, was a young man. They were prominent, operating an iron mining business that helped Washington County thrive into the 19th century.

They were also Quakers, a Christian movement that started in England and spread into the New World in the 1600s. Among the Quaker edicts, God exists in all of us, every human being. And people don't enslave other people.

Most of the family moved on in the early 1800s, heading for Ohio. But Elihu stayed back and continued to run the business. His brother, Elijah, who would marry Gov. John Sevier's granddaughter and enjoy an affluent life, joined him.

Elihu had two wives, the first of whom died after they had two girls together. His second wife was a slave owner. Embree himself acquired slaves.

Along with mining, Embree got into the shipping business, mostly to major northeastern cities like Philadelphia and Boston, Mason said.

He'd grown distant from his Quaker faith, but his business contacts proved influential in drawing him back into the teachings of the Religious Society of Friends as it was more formally known, said Mason.

Toward the end of his life, Embree would free most, but not all, of his slaves. He used a woman named Nancy and her five children as collateral in a land deal. So he wasn't in a legal position to free them when he died, Mason said.

Embree got involved in what was called the manumission movement, which sought the legal release of people currently enslaved. He joined the Manumission Society of Tennessee, an anti-slavery group that started in Jefferson County in 1815.

One of their objectives: Amend the Tennessee Constitution to outlaw slavery. At the time, one could openly challenge the norm of slavery. By the 1840s, it would no longer be acceptable as the nation rumbled closer to war, Mason said.

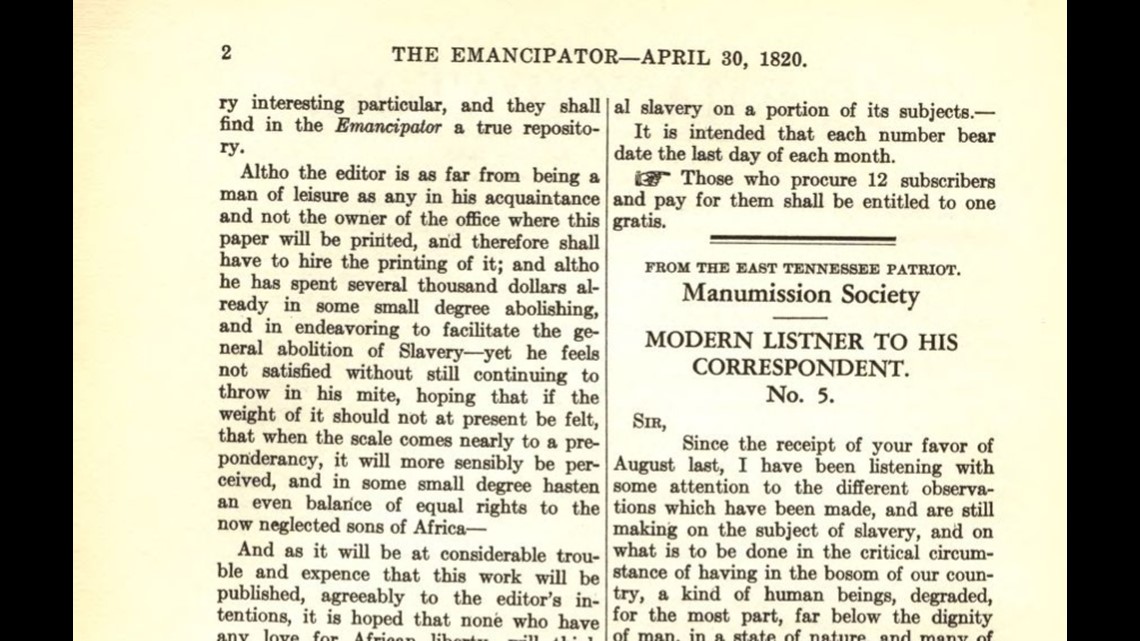

Embree first got involved in printing the society's newspaper, which championed eliminating slavery but also ran other news. It was called the Manumission Intelligencer.

According to the Tennessee Encyclopedia, published by the Tennessee Historical Society, the society's constitution required that everyone approve what went into the newspaper. They didn't meet very often, and that affected the publishing schedule.

A frustrated Embree ended up leaving the society, deciding to publish his own newspaper devoted exclusively to the abolition of slavery.

The Emancipator

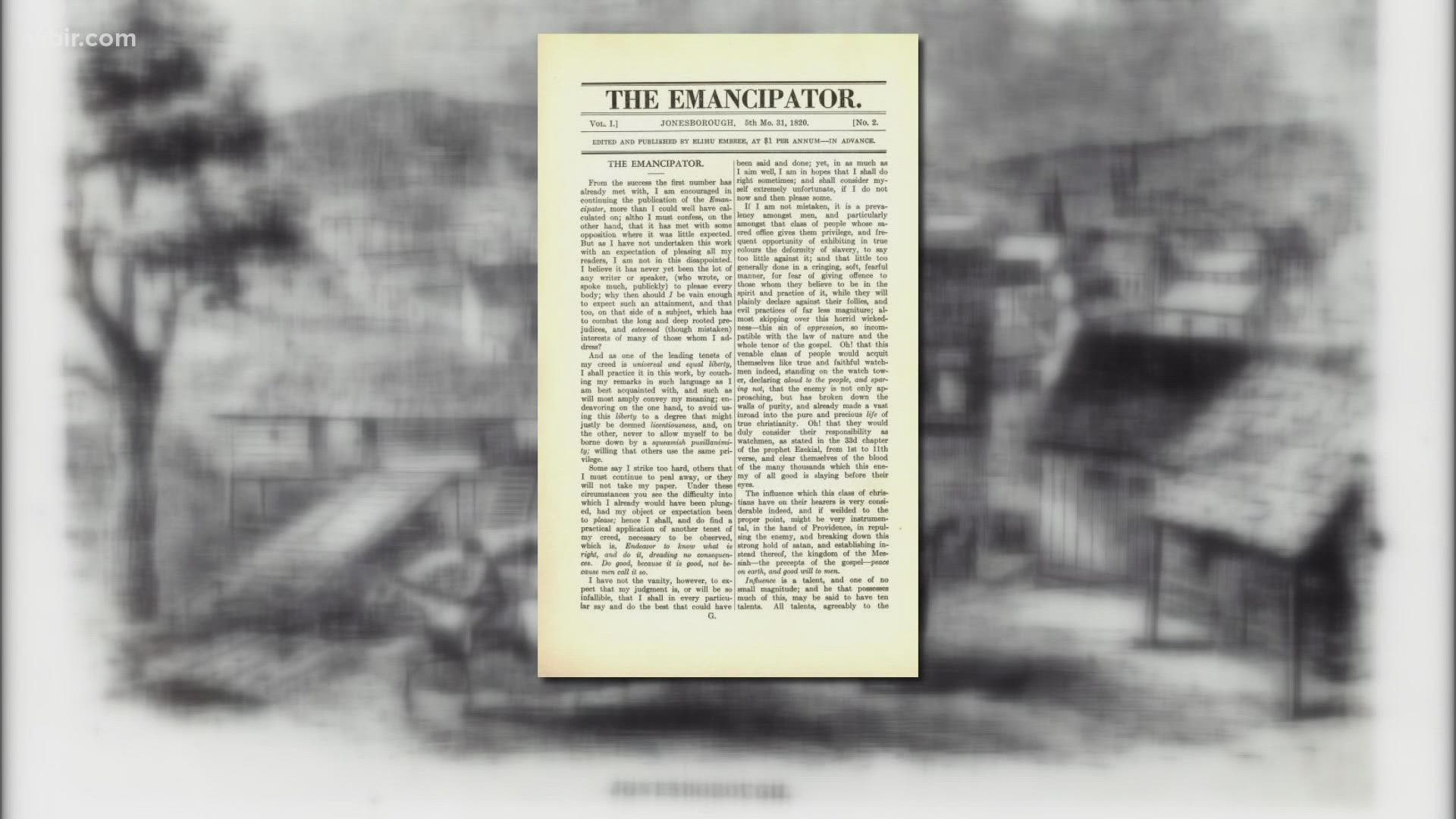

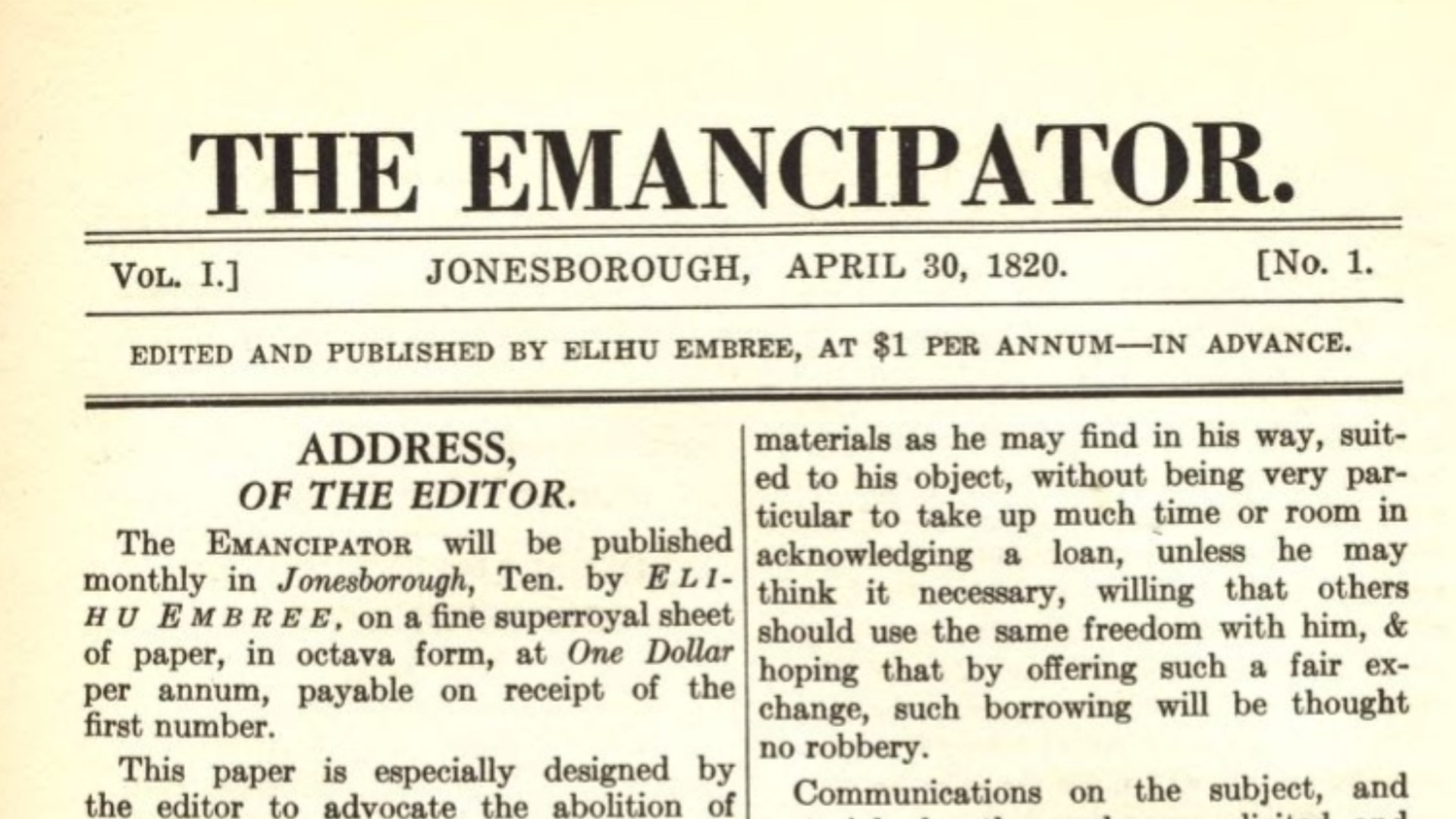

He called it The Emancipator. He prepared it in Jonesborough and took it down Main Street to a printer named Jacob Howard for a press run. The first edition appeared in April 1820 with an annual subscription price of $1 a year.

Mason suspects Embree may have had some health problems and sensed he needed to hurry up and get the paper out.

"This paper is especially designed by the editor to advocate the abolition of slavery, and to be a repository of tracts on that interesting and important subject," Embree wrote.

He'd spent several thousand dollars of his own money to get started, he told readers.

The paper printed what news he could find in the world about slavery and the slave trade as well as letters from readers, to which Embree would respond.

He made sure to send the paper to Southern governors, some of whom didn't appreciate his publication, scolding him for trying to "divide" the country, Mason said.

By issue No. 5, Embree was ready to reveal a surprising piece of information about himself.

A letter writer named "G.M." from the Nashville area alerted Embree that someone was going around telling people that Embree previously had owned slaves.

And of course, the letter writer stated, he couldn't see how that was true. Right?

"...for I know you are engaged in a work, which exposes you to censure, calumny and implacable hatred; but there are some no doubt who feed on this report with as much pleasure as a Buzzard would on Carrion," G.M. wrote.

Sadly, Embree replied, it was true. He had owned slaves.

"To my shame be it also said, I have denied for years the truth of the christian (sic) religion; and during these years I became possessed of slaves," he wrote.

He continued: "...I repent that I ever owned one."

Embree recognized and regretted his mistakes, Mason said.

"He says, the time may come where if you have messed up like I have, you may not be celebrated anymore. And he said, that's OK. Because it means we've gotten better, hopefully. So he was just really honest about what the future may look like and his own shortcomings," she said.

Remembering Embree

It was Embree's goal to publish the paper once a month for many years to come. But after his seventh edition, he could do no more.

Embree fell ill and in December 1820, he died. "Bilious fever" was the cited reason, often a reference to what we know as typhoid or malaria.

He was 38. By then, the paper had a national distribution of about 2,000, sizeable for its time.

It was Embree's wish in his final will, to be carried out by brother Elijah, that the slave woman known as Nancy and her children be freed.

Whether that really happened scholars including Mason just don't know. What happened to Nancy, who was close in age to Embree, also is unknown.

Mason last year wrote a play about Nancy, offering her interpretation about who she was and what may have happened to her.

Why Embree took pains to look out for Nancy and the children, we don't know. Is it possible he fathered one or more of the children? Mason has thought of that but can't confirm it.

Embree left behind a struggling business, a big family and a lot of debt.

Today, he is remembered by the Heritage Alliance in a museum in downtown Jonesborough.

There's also a push happening right now by Boston University and The Boston Globe to reimagine The Emancipator, to restart the conversation about race in America and give voice to those who have gone unheard in the past.

Where is he?

No one can say for certain what happened to Embree's remains.

LIkely he ended up in a hillside family plot in Washington County about 12 miles south of Jonesborough. It's off Bumpus Cove Road not far from the Nolichucky River.

Good luck finding any stone that marks his location. Trees and shrubs and the passage of time long ago took over the cemetery. Sunken patches pit the plot.

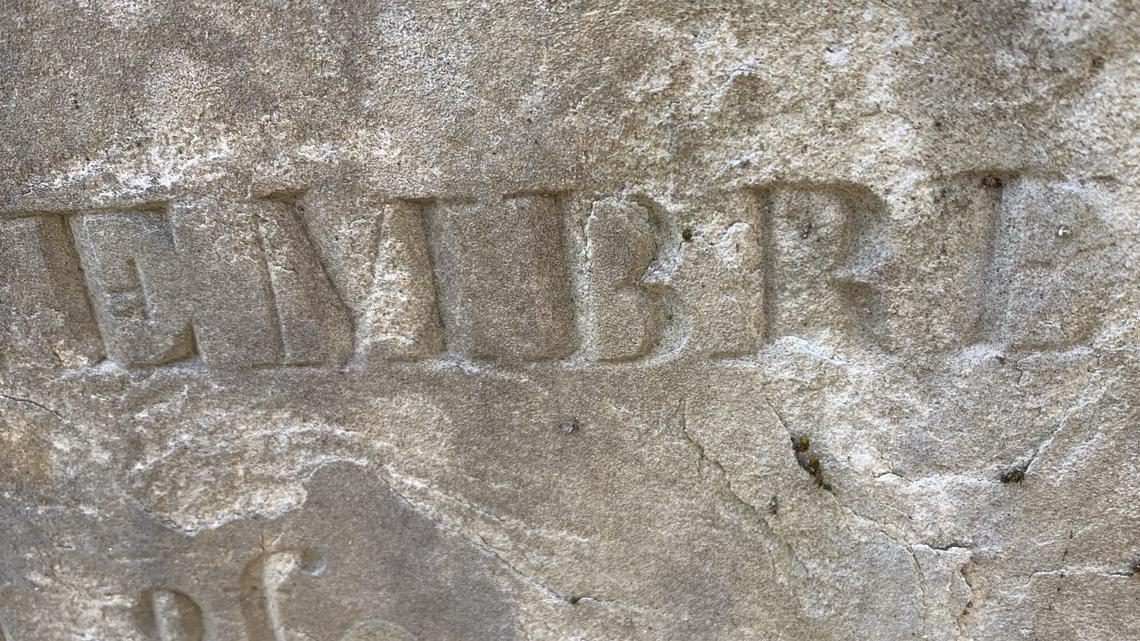

Gravestones teeter here and there, some bearing the last name Embree. It's been many generations since anyone was buried there.

Embree made an impression on history. But history has lost track of him.