When TVA finished building the Kingston Steam Plant in 1955, it was the largest coal-power plants in the world. On December 22, 2008, the renamed Kingston Fossil Plant was the site of the largest environmental disasters in the country.

It was after midnight with frigid temperatures dipping to 12 degrees when the wall collapsed on the massive ponds where TVA stored the leftover ash from burning decades of coal. The breech unleashed an avalanche of more than a billion gallons of sludge into neighborhoods and the Emory River.

We look back at the disaster 10 years ago, what has changed since then, and the ongoing legal fights over the danger and damage from coal ash, the byproduct of burning coal for electric power.

The ash spill hit Roane County 10 years ago, but the disaster started building more than half a century before that night.

POLLUTION AND DUST FROM THE START

When the Kingston Steam Plant was built in the 1950s, it was the largest coal-power plant in the world. It generated massive amounts of electricity and pollution.

In those days, the neighbors could see the dirty effects of burning coal at home. Tiny particles of fly ash flew out of nine short smokestacks at the plant and coated the surrounding community in a powdery dust.

TVA tried to keep the dust-covered neighbors happy by cleaning the ash from homes and cars for free. The plant eventually built two 1,000 ft stacks with electrostatic collection systems that captured 98 percent of the fly ash before it escaped. The ash that made it out of the colossal chimneys was high enough in the air to scatter without bothering the community.

Even without the nuisance of fly ash, burning millions of tons of coal every year continued to pump the air full of invisible pollution. Sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere devastated air-quality in East Tennessee and came down as acid rain in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

The huge plant switched from high-sulfur coal found in local mines to a low-sulfur coal from western states. Still, the plant often failed to meet Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standards by emitting too much sulfur dioxide. TVA ultimately solved the emission issue, in part by switching from the towering smokestacks to the new scrubbers at the plant today.

While most of the concerns about pollution during the first 53 years of the Kingston plant’s existence focused on the air, a mountain of waste slowly grew on the ground.

ASH PONDS AND WET STORAGE

When the Kingston Steam Plant was constructed, TVA built dams to create large ponds between the steam plant and the Emory River. Every year, the utility dumped millions of tons of ash in the ponds where it settled to the bottom for storage while keeping the dust down.

TVA knew from experience the ash ponds could be a danger to the environment. In 1969, a breech in an ash pond at a TVA plant in Virginia seeped coal ash into the Clinch and killed countless fish.

Still, the utility chose to continue wet storage throughout the system, including its largest plant in Kingston situated where the Emory River and Clinch River join Watts Bar Lake.

TVA engineers raised red flags in the 1980s about the stability of ash ponds. The utility repeatedly found leaks in the dams and seepage in the soil but continued to make small repairs rather than switch to a dry storage system that would cost tens of millions of dollars.

Three days before Christmas in 2008, the dam finally broke on a billion-dollar disaster.

DISASTER STRIKES SWAN POND

Sometime between midnight and 1:00 a.m. on Dec. 22, 2008, the ash containment area on the north side of the Kingston Fossil Plant failed.

The avalanche of ash ripped Jim Schean’s home from its foundation and shoved the house across the street while he was inside asleep.

"Windows were breaking, furniture was turning over, the house was shifting around. All the stuff I had in there could be replaced except for me,” said Schean during an interview with WBIR the day of the ash spill. “The doors were jammed shut, so I kicked a window out and climbed out the window before the house completely collapsed, because it was popping and cracking when I was climbing out. "Like I told the nurse, I don't always go to church every Sunday, but I think I'll go this Sunday."

Schean and the entire neighborhood escaped the initial ash spill with no injuries. Because it happened after midnight with temperatures in the teens, everyone was inside their homes, nobody was doing any late-night fishing on the Emory River, and there were fortunately no cars on the road buried in ash.

Angie and Jeff Spurgeon lived in the Lakeshore community and remember the night of the spill vividly.

“It was after midnight and we were about to go to bed. It sounded like an explosion or a tornado rolling through. In an instant, our whole cove was full of ash, mud, and trees. Docks were gone. It was unbelievable,” said Angie during a December 2018 interview. “We had saved for years to build that house and in an instant, we knew we could not live there anymore.”

Fear spread as millions of gallons of sludge containing toxic materials flowed in the lake where people fish and towns get their water. Dead shad fish washed ashore downstream from the spill in water choked with ash. Water intakes downstream were monitored downstream and public drinking water was never contaminated.

TVA began digging out what it could to clear the roads and using helicopters to scatter grass seeds on the mountains of ash for dust-suppression.

"You're bombarded,” said Angie Spurgeon during a 2008 interview as they were yet to find new housing. “You hear loud noises. There's a dozer next door and they're tearing down the porch of my neighbor's house. It is sinking in what a major catastrophe this is. We're going to leave there. And it was a wonderful place to live."

People directly hit by the spill looked for new housing. For residents in nearby Harriman and Kingston, concerns grew about the sludge tracked through town by heavy trucks hauling the ash away. The plant eventually installed washers to clean trucks departing the plant.

The moonscape on the ground soon had people in Roane County seeing stars. In January 2009, an out-of-state law firm paid Erin Brockovich to come to Harriman. The environmental activist famously portrayed by Julia Roberts in an Academy Award-winning movie spoke to packed house of potential plaintiffs.

"I am here first and foremost for you. And my choice of who I thought would be the best legal team to help you,” said Brockovich.

Brant Williams, then a Kingston City Councilman, was not happy with the celebrity presentation by attorneys.

"Those guys are sharks. We don't need a bunch of out-of-state attorneys and sharks roaming the waters looking for victims,” said Williams in a January 2009 interview.

‘WHOLE AGAIN’ HOMEOWNERS

TVA leaders promised to make people impacted by the spill “whole again.” TVA started buying homes for what it said was more than the appraised value, but sellers had to sign an agreement not to sue the utility in the future for any health problems.

The offers were “take it or leave it” with no negotiations. Many homeowners said the offers were too low to buy an identical house somewhere else. But refusing to take the money would leave them to live in a disaster area where ash coated their cars and clogged the air filters inside their homes.

"I said, ‘No, I'm not losing money because you screwed up the environment.’ They said we could either take what they offered us, or we could sit there and eat it. We have been eating it," said Gary Topmiller in November 2009. “It is terrible. It is just something you cannot imagine living in for 11 months."

Over time, as court decisions made lawsuits against TVA unlikely, most holdouts sold out.

"What's the point of living in a lake house when you can't get in the lake, you can't fish in, and you can't boat on it? It became where there was no choice, we had to leave," said Carol Langley in a 2009 interview with WBIR.

TVA bought a total of 180 properties impacted by the ash spill.

EPA SPEEDS UP CLEANUP

The first few months after the ash spill, TVA's crews started the enormous task of carefully removing more than 600 million gallons of ash from the Emory River. But in the early days, crews were almost doing the job too carefully and very slow. Heavy rains in the spring of 2009 frequently washed piles of ash downstream.

In May 2009, the EPA stepped in, took charge of the cleanup, and picked up the pace.

“Our main objective right now is to get the ash out of the river as fast as we can,” said EPA’s Leo Francendese in June 2009. “Dermal contact with the ash is a minor risk. The main concern is inhalation or ingestion of ash.”

"And it's somebody different than the organization that created the problem. And to have the EPA on-board I think is just so much better," said Mike Farmer, then the Roane County Executive in a 2009 interview.

The EPA began removing ash 15 times faster than before it took over. Crews finished removing ash from the river in late-spring of 2010.

The removal of ash from the river bottom was complicated by legacy pollution from the nuclear weapons plants in Oak Ridge. Dredging too deep to remove ash could potentially uncover worse contaminants that were covered with sediment. A relatively thin layer of coal ash was left in the river at the site of the spill.

With ash out of the river, Craig Zeller with the EPA took charge of a project to build an earthquake-proof wall and protective cap around the 240 acres of ash that remained on the ground. By 2015, the liner was covered by a couple of feet of clay and topsoil with green grass growing on the surface.

Cleaning up the ash spill cost TVA $1.2 billion. The utility said it never raised rates on customers to pay for the recovery because TVA makes enough to spread the cost out over 15 years and remain profitable.

The cost of recovery went beyond removing and burying ash. TVA gave millions to Kingston, Harriman, and Roane County to repair the public image of the region and invest in economic development. TVA also gave $32 million to Roane County Schools.

TVA tore down 100 of the homes it purchased and transformed the neighborhood near Swan Pond Road into public parks with trails, fishing docks, and sports fields.

As for the homes that were left standing, TVA sold 60 of them at auction in 2015. Some of the buyers were the same families forced to leave, including the Spurgeons. Their new home is across the river from the site where their previous house has been razed.

“I felt okay about coming back,” said Angie Spurgeon. “We love this part of the lake. It is where our daughters grew up. And I’m at the age where I like living on the lake but don’t get in the lake, so I’m not concerned about the ash that might still be in the river.”

Jeff and Angie said they have not noticed any fly ash or more dust than usual at their home since moving back to the lake a couple of years ago.

“We look at the ash spill like that is one phase of our life, it is over, we are not going to be bitter, and we’re moving on. I do feel bad for the workers who are saying they got sick from working in the ash,” said Angie Spurgeon.

While the Spurgeons are moving on, there is still some sadness at how the spill scattered a beloved group of neighbors.

“There were a lot of really good people who lived over there,” said Spurgeon. “A park is nice, but it is not the same.”

WATERSHED MOMENT FOR COAL STORAGE

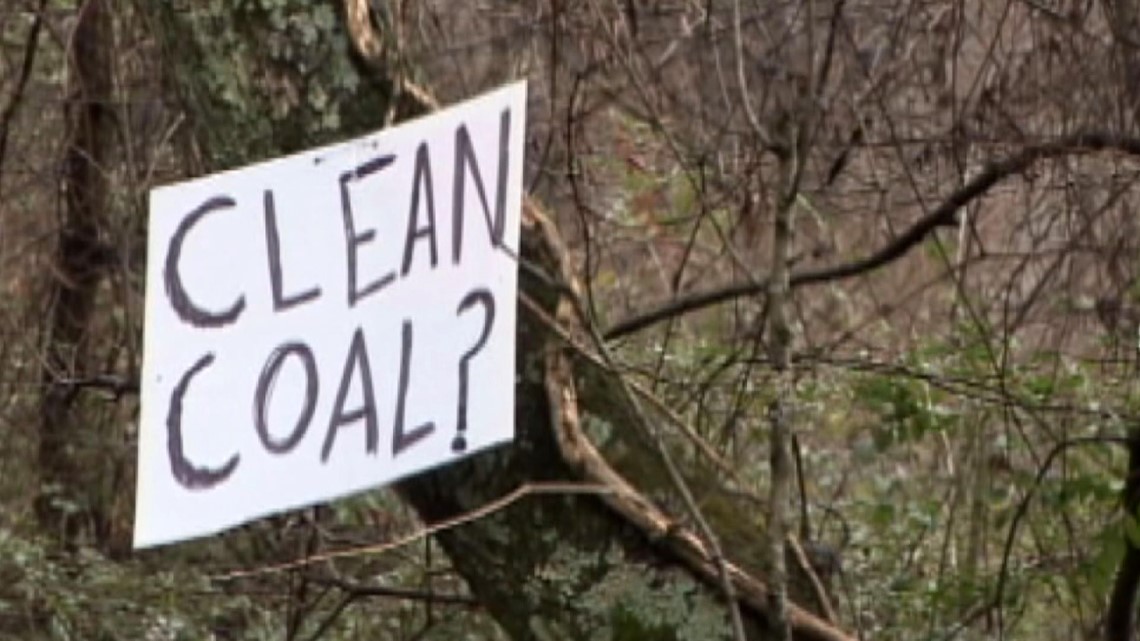

The ash spill at Kingston brought attention to the complications and risks of storing coal ash but changed in federal regulation would did not come quickly.

“This was a watershed moment what happened here on Dec. 22, 2008,” said EPA project manager Craig Zeller. “It got the ball rolling as far as what we should be doing with this material.”

The fundamental first step in regulation coal ash was deciding how to classify the material.

The concentrations of heavy metals in coal ash can be 4-10 times higher than coal before it’s burned, according to scientific studies.

“Heavy metals and toxins like mercury, lead and arsenic, and they don’t go away either, except by leaking into and leaching into our groundwater and our rivers,” Frank Holleman, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center.

Under the EPA’s framework, the two options for classifying coal ash were as a Subtitle D non-hazardous waste, or a Subtitle C hazardous waste.

Environmentalists pushed for coal ash to be classified as a hazardous waste. That classification would bring higher safety standards for both workers who handle the product and the sites where it is produced.

However, a hazardous material classification would cost utility companies billions of dollars to meet regulatory standards. Subtitle D landfills have one liner along the bottom whereas Subtitle C hazardous waste landfills have two.

“Practically speaking from the disposal standpoint, there’s really not a big difference,” Zeller said. “The problem is that in the United States, we don’t have a lot of Subtitle C landfills and to build a bunch of Subtitle C landfills to handle the quantity of ash that’s generated in the United States would take probably 10 years to get some of those built.”

In April of 2015, the EPA finalized the first rule overseeing how coal ash is disposed of. The EPA classified coal ash as a non-hazardous waste, but for the first time there would be a national requirement for new coal ash landfills, including mandatory groundwater monitoring with data that must be made available to the public. The Kingston catastrophe also prompted the EPA rule also set requirements for the structural integrity of coal ash landfills.

“It was a wake-up call because collapse didn’t occur when a hurricane hit, and there wasn’t an earthquake or a major flood. It was a failure because of poor design, poor maintenance and the inherent danger of storing such large quantities of waste in these unlined pits,” Holleman said.

COAL ASH TODAY

Kingston is one of three TVA sites where lined landfills have been built and are operational. TVA is scheduled to begin construction of lined landfills at other TVA sites across the region in 2019.

The ash is in Kingston is compressed and vibrated in the landfill using a method TVA calls intelligent compaction. Heavy machinery rolls over the ash and sensors show engineers how densely the material has been compacted. Hundreds of sensors measuring groundwater quality, water levels and movement within the landfill are monitored in real time at a TVA command center in Chattanooga.

A large quantity of TVA’s coal ash never makes it to a landfill. The EPA’s 2015 coal ash rule allowed coal ash to be qualify for beneficial reuse. Now, more than a third of TVA’s coal ash is sold and used to make concrete, roofing and other approved materials. The EPA says that coal ash reuse reduces the use of virgin resources, lowers greenhouse gas emissions, reduces the cost of coal ash disposal and can improve the strength and durability of materials.

THE COST OF LEAKS AND LITIGATION

A decade after the spill, TVA is still paying for the disaster. While property owners who sold their affected land to TVA relinquished their right to sue the utility for any damages or future medical expenses incurred by the spill, TVA is fending off lawsuits for violating clean water protections across the Volunteer State and the determining the damages done to workers who cleaned up the Kingston site is still not settled.

TVA hired Jacobs Engineering to clean up the spill. For months and years, workers toiled in the site without masks protecting them from inhaling coal ash and its dust.

A federal lawsuit filed in Federal court in 2013 claims that Jacobs Engineering failed to protect its workers from risks that come from working with coal ash and lied about the possible health impacts.

“They were making money off us and killing us at the same time,” Ansol Clark, one of the workers and a plaintiff in the lawsuit said. “When people would ask for a dust mask or something they’d say no, we didn’t need one.”

In November of 2018, a federal jury found that Jacobs engineering broke its contract with TVA and could be held responsible for the illnesses of workers ranging from high blood pressure to cancer. A date for the second phase in the trial has not been set.

TVA is not a party to the lawsuit, but the utility’s 2018 annual report says, “TVA could be obligated to reimburse Jacobs for some amounts that Jacobs is required to pay as a result of this litigation… Further, TVA will continue monitoring this litigation to determine whether this or similar cases could have broader implications for the utility industry.”

Weeks before the 10-year anniversary of the spill, the Roane County Commission set aside money to explore suing TVA and/or Jacobs Engineering.

“Right away it gave Kingston, Harriman and Roane County area a black eye,” Roane County Commissioner Randy Ellis said. “TVA has come a long way. They’ve had a huge culture change… but they’re still responsible for what they’ve done to our community and the people that are sick now.”

Even with the changes put in place after the Kingston catastrophe, TVA is still facing lawsuits and state orders for failing to safely store coal ash in Tennessee.

TVA Allen Fossil Plant in Memphis was retired in 2018, but decades of wet coal ash threatened Memphis drinking water. TVA decided to dewater that ash at the Allen plant and put in a lined landfill.

However, when a lawsuit exposed coal ash leaking through its storage pits near the Cumberland River, TVA argued that method of dealing with a problem ash facility was too expensive. A judge ruled in favor of the clean water advocated and ordered TVA to move coal ash from the leaking pit at Gallatin to a lined landfill. TVA says that move would cost $900. The utility appealed the ruling and won, but in its 2018 annual report TVA says it could be subject to similar litigation at other sites.

In addition to lawsuits by environmental watchdog groups, simply operating coal ash storage sites exposes TVA to more costs and risks. The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation ordered TVA to undertake investigations for all facilities in Tennessee. TVA’s annual report states:

“TVA could be required to restrict or stop the use of any or all CCR facilities or relocate CCR material to other lined facilities which do not currently exist. These measures would impact how TVA operates its facilities, cause TVA to incur greater expenses than currently anticipated for operating, closing, or decommissioning existing CCR facilities, and negatively impact TVA’s cash flow, results of operations, and financial condition… Additionally, the relocation of materials would result in a lengthy process with the potential for environmental and safety impacts, which could cause extensive adverse financial and reputational impacts to TVA.”

NEVER-ENDING IMPACT

After 10 years, the impacts of the TVA ash spill are evident in ongoing lawsuits and how the industry as a whole treats the byproduct of burning coal for electric power. The impacts will likely never go away as long as utilities burn coal for electricity and dispose of ash in the ground.