They met at a Gatlinburg bridge tournament, but for Cindy and David Shepler, a life together forever was not in the cards.

Late last year, the couple flew to Switzerland so she could die.

"I can’t tell you the number of times over the last five years she would say as she was going to sleep, 'I hope I don’t wake up.' And she meant it," David Shepler said.

Cindy suffered a number of painful chronic and autoimmune diseases.

One called myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome made her constantly exhausted. A trip to the movies or a hair appointment required a full day of rest before and after.

"She wasn't exactly bedridden," David Shepler said. "But it was very, very difficult for her to leave the house."

In recent years, doctors diagnosed Cindy with more painful illnesses. Two targeted her skin, making her blister easily in low heat and feel as if her flesh was on fire.

Her husband said the sicknesses had no treatments, no cures and were only getting worse. She could no longer physically live the life she wanted to.

"She was very tough," David Shepler said. "She had learned to live with [myalgic encephalomyelitis], but as these other things kept piling on it made her life a living hell."

That's when she decided she wanted to fly to Switzerland, where doctors could help her die.

A lifetime of pain

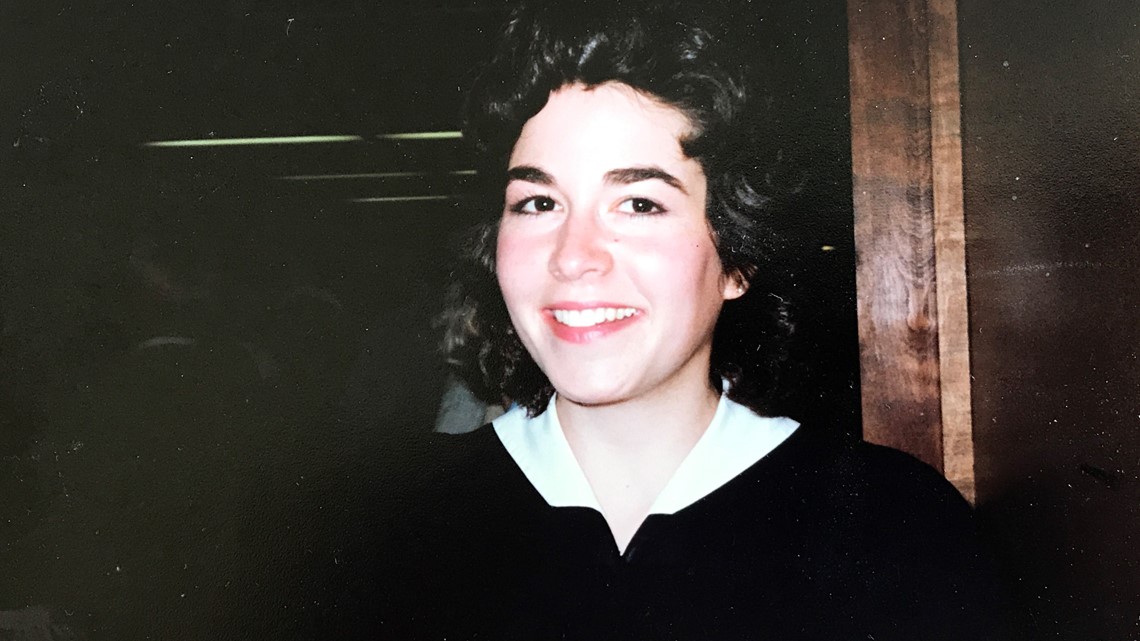

Growing up in Knoxville's Sequoyah Hills neighborhood, Cindy Shepler was one of three siblings. Her father was a successful CPA and her mother a homemaker.

After high school, she took a gap year to work in a shoe store near the University of Tennessee. Then, she traveled to the West Coast for college.

Her husband said it was in her twenties when she was first diagnosed with thyroid problems and had the gland removed.

She joined Cigna and became an account executive, until 1993 when her illness made it impossible to continue to work.

"It just kept taking a toll and progressing until she just literally did not have the physical stamina to work full time," David Shepler said.

In the early 1990s, Cindy Shepler traveled to the Cleveland Clinic where doctors diagnosed her with myalgic encephalomyelitis.

Over the next twenty years, her physical health continued to deteriorate.

"Toward the end she felt like a prisoner feeling tortured," David Shepler said.

"I was 100 percent behind Cindy," Shepler said. "It was going to be a great loss to me but when you love someone and you see them suffering daily and getting worse and sometimes she would scream in agony. I had no reservations about it – it was her decision, I never suggested it. But I never talked her out of it either."

A medically-assisted death

David Shepler said Cindy did not qualify for so-called "death with dignity" in any U.S. state which allows it.

'All of her conditions were going to shorten her life but not by enough by medical standards," he said.

She applied to a Swiss group which facilitates medically-assisted deaths for terminal illnesses and sicknesses where quality of life is severely diminished.

When she was accepted, David said Cindy let out a scream of happiness.

"If you can think of what a joyous primal scream would sound like, that’s what it was," he said. "She said in her own mind, that reaction proved to herself if she had any doubt, deep down inside this is what she wanted and needed."

The pair made arrangements for a taxing journey across the Atlantic Ocean and only shared their plans with a few family members.

After mental and physical health screenings and an interview, the Sheplers went to a small clinic where a doctor prepared to give her an IV.

They spent a final few minutes together, before Swiss law required Cindy Shepler to turn a nob to start the IV herself.

"Part of me wanted to reach out and stop her and hug her and tell her everything would be better, but that’s the emotional part," David Shepler said. "I had to keep reminding myself that this was best for her, that her pain and suffering were over and that’s what she wanted and she needed."

Her ashes were spread in a Swiss river.

Raising awareness

"We all want our life to mean something, our death to mean something," David Shepler said. His wife, Cindy, was no different.

In life, she advocated for a variety of awareness and medical organizations related to her conditions.

She even worked to have now-former Knoxville Mayor Madeline Rogero and city council declare May 12 "myalgic encephalomyelitis" day.

David Shepler said she wanted her death to raise awareness too, about the conversation surrounding the right to die.

He recalled one conversation with Cindy Shepler after her cats got sick.

"She made the very difficult decision to euthanize them and always said 'We treat our pets better than our fellow human beings in that regard.'"

Medically-assisted suicide is not without controversy. The American Medical Organization said on its website "permitting physicians to engage in assisted suicide would ultimately cause more harm than good."

In most U.S. states, it is not legal.

But David Shepler said it's important to note his late wife was not advocating for suicide. He said she never thought of her death that way.

"She was doing what she had to do," he said. "It was not a rash decision by any means. It was something she struggled with and it went back to a paper she wrote in 2017: When is enough, enough? And that day finally came."

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, help is available. Call 1-800-273-8255.